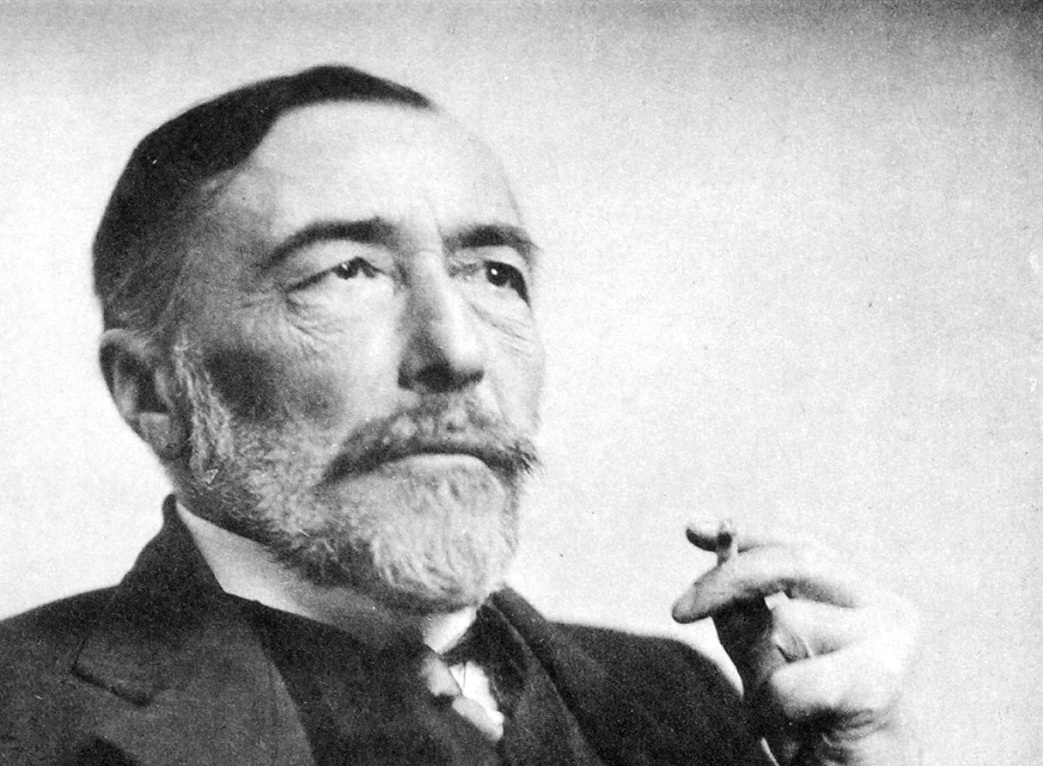

Utter it softly, but with a few rare exceptions the moral arbiters of our age have still failed to come for that master of realist storytelling tinged with philosophical digression, Joseph Conrad (1857–1924), who died one hundred years ago this August. It may be that Conrad and Evelyn Waugh remain the most accomplished prose writers of the twentieth century to thus far avoid the basilisk stare of the numerically tiny but implacable ranks of those who act as the censors of our modern public discourse.

While Conrad has escaped the sort of bowdlerization that has befallen everyone from Mark Twain to J. K. Rowling, he hasn’t entirely eluded the radar of the world’s grievance class over the years. As far back as 1977 the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe, youthful author of the postcolonial satire Things Fall Apart (1958), published a widely circulated essay taking issue with some of the themes at play in Heart of Darkness. According to Achebe’s reading of the book, Conrad was a “talented, tormented man” who had reduced the indigenous characters of his tale to mere “limbs” and “rolling eyes.” He reserved particular opprobrium for a line Conrad had written describing his narrator’s encounter with a wandering native: “A certain enormous buck nigger encountered in Haiti fixed my conception of blind, furious unreasoning rage, as manifested in the human animal to the end of my days.”

The very core of Conrad’s novel, its mythic descent into illness and disillusion by a white merchant trekking through the Congolese jungle—very much the saga of Conrad’s own experience as a freelance sailor before becoming a writer—is for Achebe a white fantasy in which Africa is a mere backdrop: “Can nobody see the preposterous and perverse arrogance in thus reducing a whole continent to the role of props for the break-up of one petty European mind?”

Of course, Achebe may fail to distinguish between the surface narrative of Heart of Darkness and the book’s deeper insights—some of them of a subtlety that might tax the reader predisposed to be offended—into the preeminence or otherwise of the white man’s system. It is hard to read the book in full, as opposed to filleting it for provocative tidbits, and come away with the impression that the author has made a case for the superiority of the European colonizing class on any genetic or biological grounds. Perhaps the Achebe school has failed to note, too, Conrad’s extraordinary short story, the ironically titled “An Outpost of Progress,” whose publication preceded by two years that of Heart of Darkness. The tale is set in a remote trading station located on the Kasai River, a tributary of the Congo, where two European travelers, named Kayerts and Carlier, are revealed as superficially “civilized” but morally hollow in their dealings with the natives. Speaking of his own emotions at the time he wrote the story, Conrad said: “All the bitterness of those days, all my puzzled wonder as to the meaning of all I saw—all my indignation at masquerading philanthropy—exploitation masked by idealism—have been with me again while I wrote . . . I have divested myself of everything but pity—and some scorn.”

Since Conrad’s story ends with a trivial quarrel between the two Europeans, at the climax of which Kayerts shoots the unarmed Carlier and then hangs himself in a fit of remorse, it can hardly be read as a tribute to the invariably higher plane of the white man’s culture.

There is a long tradition of critics misunderstanding Conrad, surely in part because both the man himself and his works are so full of humanizing contradictions. He was the youthful adventurer who developed a debilitating need for domestic order and stability; the forbiddingly austere chronicler of man’s fallen nature who could turn a comic phrase with which P. G. Wodehouse might not have been disappointed (such as this from 1915’s Victory: “Heyst’s smiles were rather melancholy, and accorded badly with his great mustaches, under which his mere playfulness lurked as comfortably as a shy bird in its native thicket”); a hypochondriac who was an all-too-real martyr to gout and toothache, neither of which served to mollify a personality already prone to the choleric; a curious mixture of patriotism and skepticism; a native Polish speaker justly celebrated for his mastery of the most intricate nuances of the English language who struggled all his life with what he called the “elusive mother tongue,” only coming to speak it in his early twenties; and a man who for the most part hid himself behind a mask of inscrutable courtesy.

As H. G. Wells noted, expressing a widely held view of those who came into direct contact with Conrad: “He impressed me as the strangest of creatures. . . . [He had] a trouble-wrinkled forehead and very troubled dark eyes, and the gestures of his hands and arms were from the shoulders and very Oriental indeed.” To this the poet Henry Newbolt, of “Vitaï Lampada” fame, added:

One thing struck me about Conrad at once—the extraordinary difference between his expression in profile and when looked at full face. While the profile was aquiline and commanding, in the front view the broad brow, wide-apart eyes and full lips produced the effect of an intellectual calm and even at times of a dreaming philosophy. Then . . . I saw another Conrad emerge—an artistic self, sensitive and restless to the last degree. The more he talked the more quickly he consumed his cigarettes . . . And presently, when I asked him why he was leaving London after only two days, he replied that the crowds in the streets terrified him. . . . “I see their personalities leaping out at me like tigers.”

Whatever Conrad’s virtues as a writer of unusual perceptiveness, with a gift both for physical detail and the deftly sketched character study, he was not, with the best will in the world, an author whom we could imagine joining the modern artistic crowd offering their distractions of perpetual rainbow theater while developing their own social media platforms and vainly lecturing on the looming apocalypse of climate change. The man was a closed book. Consider Conrad’s reaction to becoming a father for the first time at the age of forty, an event he seems to have regarded with the same level of enthusiasm he reserved for one of his bouts of arthritis. His long-suffering wife, Jessie, would later recall the three family members making the short train journey from their home in the English countryside to visit the writer Stephen Crane.

“He had taken our tickets,” she wrote, “and intended traveling in the same carriage, but—here he became most emphatic—on no account were we to give any indication that he belonged to our little party. . . . [He] seated himself in a far corner, ostentatiously concealing himself behind his newspaper and completely ignoring his family. . . . The baby whimpered and refused to be comforted. I caught a glance of warning directed at me from over the top of the paper.”

Conrad spent much of his later life in England, which could never quite decide what to make of this singular figure. Usually in need of money, he became interested in his final years in the lure of Hollywood, going so far as to write a treatment he submitted to the Famous Players Corporation of a script he called “The Strong Man.” Since this was to be a silent picture, Conrad’s words, had they been used at all, would have been restricted to a series of on-screen printed exchanges, interspersed with descriptive passages, of which a few fragments remain:

“You are a rebel. I will have you shot.”

“I care not. I was forced to serve.”

Dona Erminia walks down the path with a dish of boiled maize, in which there is a wooden spoon, in her hand. She hands it to him with perfect aloofness and he receives it with grateful humility.

Not great, perhaps, but at least evidence that Conrad was several years ahead of the likes of William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Nathanael West among the legions of “jerks with Underwoods”—to paraphrase the studio chief Jack Warner’s famous putdown of screenwriters—who proved unequal to the task of selling their literary birthright for a mess of pottage. A sculptor attempting to do a plumbing job, in the end Conrad abandoned his script as “a merely vapid and horrible tale, as anyone can see,” and alas the Famous Players magnates hastened to join the consensus.

Nonetheless, there are distinct cinematic touches to The Rover, the last of Conrad’s novels to appear during his lifetime, including this description of the coast of Toulon, which resembles nothing so much as a panning shot that moves from the Mediterranean sky, over fields lush with vegetation, onto a row of gaudily painted peasant cottages in the foreground: “There were leaning pines on the skyline, and in the pass itself dull silvery green patches of olive orchards below a long yellow wall backed by dark cypresses, and the red roofs of buildings which seemed to belong to a farm.”

Nor did the humiliations meted out by Hollywood deter Conrad from setting sail in April 1923 for New York, where he hoped—like Dickens and Wilde before him—to begin a lucrative lecture tour of America, but instead found only a mob of reporters waiting for him at the quayside, a reception that placed what he called “intolerable strain” on his already fragile PR sense. “I will not attempt to describe to you my landing, because it is indescribable,” he told Jessie, who remained behind in England. “To be aimed at by forty cameras held by forty men that look as if they came out of the slums is a nerve-shattering experience.” Again the hoped-for riches failed to materialize, and even a reception thrown in Conrad’s honor by the publisher Frank Doubleday proved disagreeable when a loaded Scott Fitzgerald drove out from his nearby home in Great Neck and danced an animated jig on Doubleday’s lawn before being escorted off the grounds by a caretaker, surely another distasteful episode for one as fastidious in his own behavior as Conrad. The latter was then aged sixty-five and a figure pitiful in his suffering. His gout, toothache, arthritis, and migraines were ever worsening, and on top of that his firstborn son Borys was already running into the money difficulties that would eventually see him convicted of fraud and sentenced to prison for a year.

In March 1924, Conrad, back home in rural England, sat for a bust by the eminent sculptor Jacob Epstein, who left a poignant account of the process:

Conrad gave me a feeling of defeat; but defeat met with courage. He was crippled with rheumatism, crotchety, nervous, and ill. He said to me, “I am finished.” There was pathos in his pulling out of a drawer his last manuscript to show me that he was still at work. There was no triumph in his manner, however, and he said that he did not know whether he would ever finish it. “I am played out,” he said, “played out.”

The book, entitled Suspense, was never finished. On the morning of August 3, 1924, Conrad suddenly sat up in bed, gasped the words “Here . . . you” and then fell back again, dead, at the age of sixty-six, of a heart attack. He was given a Catholic funeral, which, in a faintly macabre touch he might have enjoyed, took place amidst the gaiety of his hometown’s annual summer street fair. At Conrad’s prior request, the epigraph from Spenser’s Faerie Queene—“Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas / Ease after warre, death after life, doth greatly please”—was cut into the gray granite of his headstone.

With Conrad, irony was all. If there’s a throughline to his fifteen novels and scores of stories, essays, and memoirs, it lies in that peculiarly English art of distancing—perhaps all part of his long and by all accounts highly successful assimilation into the role of an Edwardian country squire—that thin film maintained between oneself and the rest of humanity. Almost everything he wrote appeared to come pinched between inverted commas, and he took a cold-eyed view of the world as a place of mystery and contingency, of horror and redemption, where, as he once put it in a letter to the London Times, the only indisputable fact of man’s existence is “our ignorance.”

Conrad’s understanding of this truth, adding a metaphorical force to his gifts for conveying the tragic or merely ludicrous aspects of the human condition, surely serves to make him the first great “Modernist” author of the twentieth century, not to mention a moralist whose higher sensibilities might compare favorably to those of his critics today.