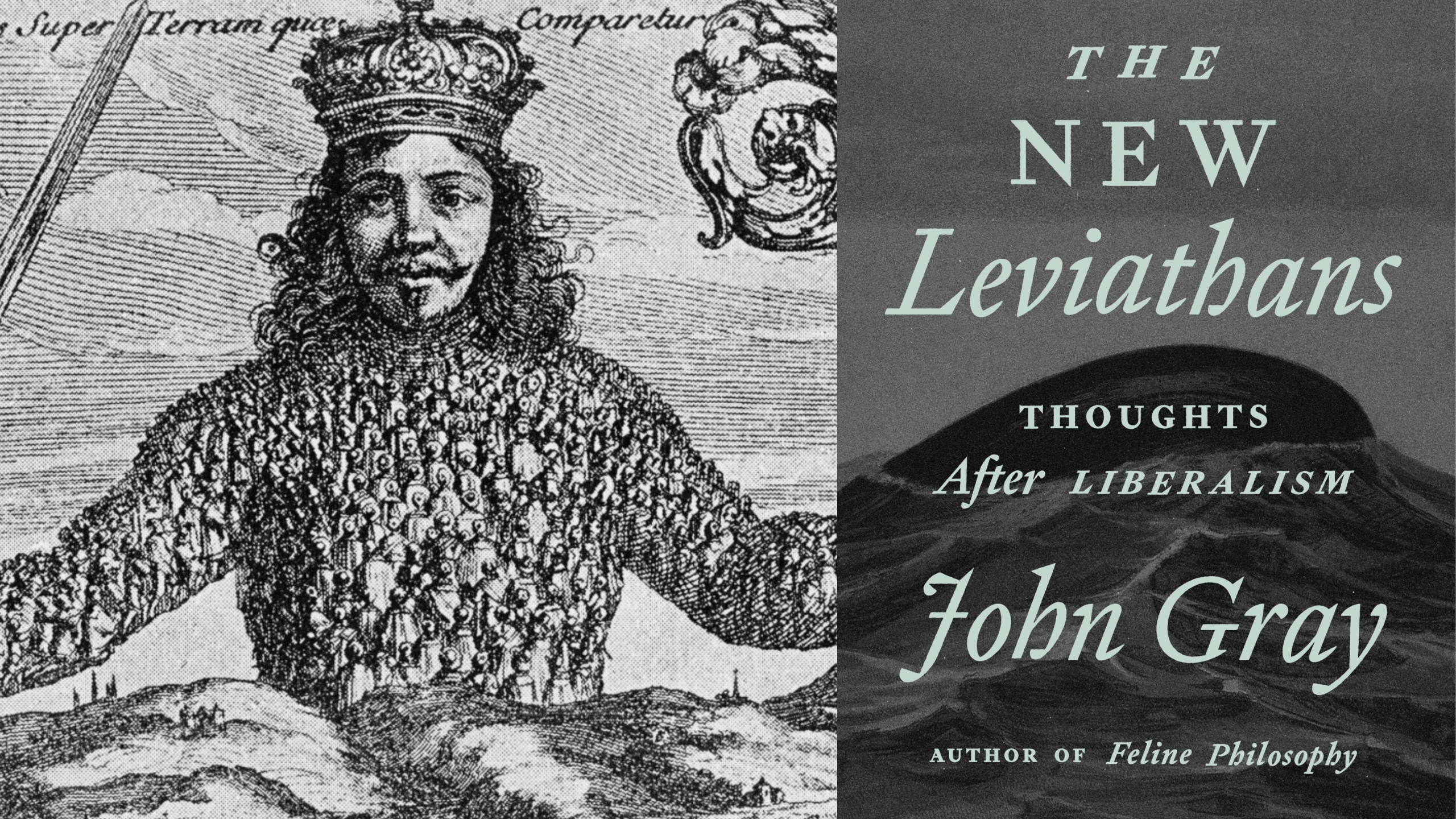

John Gray, emeritus professor of European thought at the London School of Economics, was a postliberal long before the label came into vogue. His latest book, The New Leviathans: Thoughts After Liberalism, examines the superstitions of progress and twenty-first-century troubles by the light of Thomas Hobbes’s philosophy. Gene Callahan recently interviewed Gray for Modern Age. The transcript has been lightly edited. —ed.

Gene Callahan: Michael Oakeshott once said that he liked events like this to be “an unrehearsed intellectual adventure.” So we can go anywhere.

I mentioned that to someone who had been at his lectures, and the person said, oh, his lectures were never like that.

John Gray: No, they weren’t. I knew him personally for the last twelve or maybe fourteen years of his life. I only saw him lecture once or twice. He was very methodical and formal when he did that. But his conversation was extremely vivid and free-ranging. And funny.

GC: Well, I like the ideal.

I’m a serial reviewer of your works, and I sometimes disagree with things, but I’ve always found my time was well spent.

So let’s start with the matter of style. I recently compared what you were doing in nonfiction to Milan Kundera in fiction. After I sent that to you, you agreed to the interview. So I thought, either he thinks I have a good idea of what he’s doing or he thinks I’m in serious need of correction.

JG: It was the former. I’m fond of Kundera’s work. I like his combination of humor and absurdism, and an attempt—which he probably never put like this—to probe what it means to be a reflective human being at this point in history. So I was flattered by your reference rather than thinking you needed to be corrected.

GC: In The Art of the Novel he actually lays out what he’s doing. He says a novel should be an extended meditation on a topic. I thought that was a good synopsis of what you’re doing. I’ve seen some people saying [about The New Leviathans], “There’s not a coherent argument here.” But Gadamer points out that Plato often was not presenting a coherent argument; Jesus, Buddha were hardly ever presenting coherent arguments.

JG: I wouldn’t compare myself with those. But I’d put it a bit differently: “coherent argument” means something in a constipated academic style—that’s what they mean by a coherent argument.

There are historical investigations, but I choose not to put them in the form of a treatise. There I might differ from Oakeshott because he did write treatises. He wrote Experience and Its Modes and later On Human Conduct, which I would say are treatises, though they’re full of stylistic invention and aphoristic passages and allusive and poetical digression.

I don’t take any notice of those kinds of criticism because they’re usually written by people who dislike my views intensely and therefore try to deflate them by saying, this is not a coherent argument—which, as I say, means it’s not in a style they recognize as being one in which arguments are conducted. But that’s their view. They should read something else. I don’t care whether I have those readers or not.

GC: The circumstances that prompted Hobbes to write Leviathan have again become salient in our time, as the liberal world order that prevailed for some years collapses around us. If you had to do a one-sentence summary, would that be a decent one?

JG: Yes, it would, because one of the observations that I make in the book is that it could reasonably be argued that the principal breakdowns in civilization that occurred in the twentieth century were the work of states—they were the work of very strong states, what came to be called totalitarian states—and it was the power of the state which destroyed traditions and practices and norms and values in much of Europe, in Soviet Russia, and indeed in other parts of the world. But in the twenty-first century, I think an equal or greater threat to what should be called civilized norms comes from weaker states—failed or failing states—or from anarchy.

That was combined with something else which Hobbes wrote about: the infusion of politics with the passions of religion. They were the two of the features to which he responded: the breakdown of the state in England in the civil war and the fact that on the continent (and indeed in England) wars had become conflicts of religion. So I think the recurrence of those features in the early twenty-first century is a Hobbesian situation. Therefore, it seems timely and topical to revert to Hobbes in this way. So I think your one-sentence summary was completely accurate.

An equal or greater threat to what should be called civilized norms comes from weaker states—failed or failing states—or from anarchy.

GC: If the recent events in Gaza had occurred before you finished your book, would you have included a section discussing them?

JG: I would have made some reference to them. I don’t know whether it would have been a section. They’re peculiarly horrifying because to me at least—and should be, I think, to others—the atrocities that were committed by Hamas in the attack of (or as I’ve called them more recently, the pogroms of) October the 7th were actually livestreamed and broadcast by them, not covered up. They took pride in them. And that’s still the case as far as I can tell. This was a kind of self-conscious rejection of or rebellion against civilized norms which even exceeds much of what the totalitarian states of the last century did, because the Soviets covered up the Katyn massacre and Hitler tried to keep his fingerprints off the Holocaust. At that time civilized norms still had a certain weight inasmuch as powers that violated them at least on occasion tried to conceal the worst violations—but Hamas didn’t. So I would have included a reference to it, certainly, yes, if that had happened while I was writing the book.

GC: We seem to have kind of a cul-de-sac situation there, where both parties have trapped themselves. There’s no easily apparent way out.

JG: I can’t see one at present. The demand for a ceasefire which is being made by international organizations and progressive opinion throughout the world seems to me to be flawed—I mean a long-term ceasefire, not just the short-term one around hostage negotiations that occurred—because it would create a hiatus in which Hamas could recoup its forces and plan further attacks, as its leaders have explicitly and overtly said they will. We don’t need to be in doubt about their intentions: they broadcast their intentions just as they broadcast their atrocities. I don’t see that route going anywhere.

On the other hand, I have to also say that I don’t see Israel as having a clear endgame in mind. What’s going to happen to Gaza, and to the two million people who are still there, after it’s been devastated in the course of this war? Who’s going to administer or govern it? No one wants to.

GC: Curtis Yarvin suggested that Israel unilaterally declare that Gaza is Egyptian territory.

JG: I don’t think the Egyptians would take very kindly to that.

GC: No, I’m sure they wouldn’t. But that’s why he said it should be unilateral.

JG: But if it’s unilateral, it’s meaningless. Because you can unilaterally declare anything, but for it to actually become Egyptian territory that has to be accepted in some measure by Egypt. And so it’s absolutely not going to happen that way: that’s a verbal way out of a situational deadlock. It’s just verbal, and so it’s an illusion.

But I do see it as very profound to use the word that you used earlier, cul-de-sac—that’s what they’ve gotten themselves into. Nor do I necessarily see escalation into a larger conflict. There could be an escalation by the Israelis into Lebanon, although the United States will do everything it can to prevent the Israelis doing that. Or there may be an escalation by Iran or its allies in Lebanon, though it doesn’t seem at the moment that the Iranians are very keen on that either.

So what one could have, I suppose, is a punishing and humanly very, very costly war going on for a long time. We could even see a situation like that which is perhaps developing in Ukraine, where there is an almost permanent condition of warfare—after all there has been one on and off in Lebanon for a long time in that region—and neither escalating nor coming to any clear conclusion, but freezing for periods and then resuming in different forms at different times. That’s all I can see at the moment.

And I do not see solutions in what the so-called international community is proposing because they are making a misjudgment of this war based on the belief that the Israelis can conduct what would be, by international standards, a fully just war in circumstances where the other side has essentially weaponized the civilian population. A civilian population has been weaponized if they’re used as shields and if their institutions or hospitals and schools are used as fronts for tunnels and other types of infrastructure—then the Israelis can’t fight this war according to the full rigor of international law or of some theory of just wars. It’s impossible. So it’s a very terrible and tragic situation, of a kind that does recur in history and is recurring now.

The essence of a tragic situation of this kind is that there is no solution that does not incur irreparable loss or even irreparable wrong. I think that’s what’s being missed by the so-called international community. But I have no solution myself, I’m afraid.

GC: In London, also here in the U.S., there have been massive pro-Palestinian demonstrations. They’ve been shutting down bridges and so forth. What do you make of this phenomenon?

JG: Well, I wonder why there weren’t similar demonstrations when Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, was leveled to the ground by Russian forces. They were Muslims; they are Muslims. It was a very brutal and terrible war that unfolded there. Many were tortured. Many women were raped, sexual violence was used as a tool in that war, gay men were murdered. So it was way beyond anything that has yet happened in the war against Hamas, yet there was barely, as I can remember, a single demonstration anywhere in the world, just as there have been very few about the treatment of another Muslim people, the Uyghurs, in China.

And that’s only to focus on Muslims. If one thinks also about the situation with the Tibetans, there have been some protests on that but nothing like this great convulsion. So maybe it’s motivated by concern for the Palestinians—but it seems to be motivated by other impulses, which include those which are inculcated by progressive ideology, according to which the principal (if not almost the only) source of injustice and evil in the world is the West.

Whereas on any reasonable view, the West would be culpable in many circumstances, it would be radically flawed in many circumstances, it would have committed many historical injustices—as every other civilization has done, and as other states and regimes in the world are now currently doing. So I regard these demonstrations as an expression of the progressive ideology, or, as I would prefer to perhaps think, the progressive pathology of opinion in the West. It doesn’t have much to do with Palestine as such.

I also have to say that I think there is an underlying anti-Semitism in this because why are the Israelis singled out rather than any of these others? India in Kashmir is another example. Why are they singled out? Why is no one any longer talking about the Taliban’s repression of women and gay people in Afghanistan? So I do see a renormalization of an intellectual kind of anti-Semitism—not just a conventional social anti-Semitism, which existed in Britain and America and elsewhere in much of the twentieth century, but the intellectual anti-Semitism that developed in Europe in the twentieth century. It has been happening for quite a long time because progressive opinion has always applied much more severe standards to Israeli behavior than to any other state. But it’s now assumed a really strong form. I think that’s something that has to be understood. And it’s quite a sinister and dangerous development, but this particular kind of anti-Semitism has been renormalized in public discourse.

GC: You mentioned Tibet, and I had the thought that the main thing that situation prompted is a number of bumper stickers.

JG: Well, that’s perfectly legitimate, and I’m glad that people do them. But there’s a contrast between that response and this much larger and more spasmodic response to the Palestine situation. It’s perhaps analogous to the way in which the West is accused of spreading famine and distress, hunger, around the world by its particular type of capitalism that it has now. But one of the biggest famines of the twentieth century, namely that in Ukraine, was entirely the work of a state: it was the work of the Soviet state, it was deliberate, it was not a failure of the weather or some other natural event. It was a humanly constructed famine, but it was systematically covered up in the 1930s in America by the New York Times’s Walter Duranty and in Britain as well, by nearly everybody except one or two brave journalists who insisted on speaking about it. It was covered up, and that kind of progressive mentality which existed in the ’30s has reemerged even stronger than ever because it now pervades not just some sections of the intelligentsia but large sections of institutions beyond academia, beyond universities, beyond even the media—it extends into cultural institutions, museums, right across the board.

As I say in my book, that’s one of the differences between the repression of intellectual freedom in the twentieth century and now, because now as it occurs in formerly liberal societies, it’s self-imposed. It’s not the state which is imposing limitations on intellectual freedom on museums or professional associations or universities or the media; they’re imposing them on themselves. Even in the ’30s that wasn’t the case: there was a wide variety of media and institutions that were outside of politics altogether.

By the way, I would agree with Oakeshott and other conservative thinkers that a nonpolitical domain in society is an essential part of a society being free or liberal. If everything is politicized, if every human relationship and interaction is politicized, then you no longer have a free society, whoever does the politicization—whether it’s the state, an authoritarian or tyrannical state, or the institutions that used to constitute civil society itself, as now.

GC: You mention wokeness as a focus on trivialities. The source code for computer programs is often stored on GitHub these days. And the main channel of the source code was called the “master branch.” There was a big event two years ago where “master” invoked slavery, and they renamed it the “main branch.” My thought was, you know, that kid who’s living in the housing projects surrounded by gangs and crack vials certainly will appreciate that GitHub has renamed the master branch the main branch. His life is going to be immeasurably better now!

JG: Yes, he’ll be thrilled sitting there in his basement—terrified still of being killed, but he must be thrilled that there are people who have not forgotten him.

GC: So rather than a step in the right direction, it’s a way of distracting from the fact that no steps are being taken.

JG: I agree with that completely. I think it illustrates two factors. One is the turning away from real, actually existing human hardship, and despair even, to these micro-aggressions and linguistic issues, which can, of course, be easily solved: the advantage of focusing entirely on language is that if you can gain control of the language and make a simple change from “master” to “main,” then you think you’ve resolved something in the real world. You’ve resolved absolutely nothing in the real world; the real world goes on, but it flatters the moral vanity of those who make these changes. They don’t have to sacrifice anything; they don’t have to suffer in any way. And they don’t actually have to do anything beyond passing motions to change these terms, these words. So I think it is the avoidance of very difficult human misfortunes and in some cases human injustices by looking at signifiers of oppression, which can easily be altered, even though the world isn’t altered at all. One could even say that the world is made worse by these kinds of diversionary tactics because they replace what used to be a left-wing project (or a variety of left-wing projects) that did engage with issues, that was concerned with the powers of trade unions, with getting decent housing, with providing medical care for people, and which sometimes succeeded for a while.

I grew up in the northeast of Britain; I was born in 1948, and I grew up in the 1950s and ’60s, which were shaped by the postwar Labour government, which had brought in a number of sweeping reforms in health care and schooling and housing, all of which had some negative impacts but were, on balance, highly beneficial to many people. I remember being visited at home by a doctor when I had measles as a child, at a time when Britain was poor, but there was a national health service in which doctors would come visit your home when called for what would now be regarded as relatively trivial ailments—or they won’t come at all now. That actually happened.

The world is worse from the deflection of energy away from grappling with actual human situations and their material components—the availability of resources for medical and other matters—and instead moving into the magical thinking which imagines that a change in semantics equals a change in the world. This kind of movement is politically damaging as well as intellectually worthless.

GC: The homeless are now the unhoused.

JG: Who unhoused them—how did they become “unhoused”?

GC: They’re still just as cold, but now we have a kinder word to use.

JG: Why are they called “unhoused” rather than homeless? Because “home” is a reactionary word?

GC: I have no idea about that one. But in the U.S. it’s very trendy to say “unhoused persons” instead of homeless people. It’s a shibboleth, right—you just shift the term and it shows that you’re up to date.

JG: And virtuous, yes. And it excludes people who might still want to use the old term. It has that effect as well, of confining access to public discourse to those who share not only the new term but all of the values and norms and absurdities that go with it.

GC: At one point, page 22, you say, “While history is not the unfolding of reason, there can be logic in particular situations.” I was curious here: my metaphor to express my curiosity is, let’s say I found what looks like a book, but I open it and it’s page after page of random letters just poured out. And all of a sudden, I find two pages that I can read and that make sense. Then I go a little further and find the same thing again. I’d be very curious as to what was going on: if this is a random process, how did I all of a sudden get a page where there’s logic and I can read the logic of the situation?

JG: That’s very similar to what Borges imagines in his story “The Library of Babel,” isn’t it? Which is that people spend their lives in this universal library looking for the random book which actually makes sense.

But I think it’s important to recognize, as I think I explicitly say in the book, that the logic that inheres in particular situations is in no way necessarily benign or emancipatory.

By logic, I do not mean the Hegelian logic in which there is a progressive unfolding of some human self-realization or anything like that—by logic of a situation I simply mean a set of circumstances in which certain options are closed off and others become more and more tightly bound into the situation.

I don’t believe anyone sat back in 1910 said, let’s have a war in four years’ time. Various statesmen did various things for reasons they thought were satisfactory. There were other actors, such as terrorists who assassinated various key figures. And the upshot of that was the Great War. I guess one of the questions about history is if one can actually identify the situation at the time, rather than retrospectively, in which there is an inherent logic and it’s working itself out and other options are closed. It may be, for example, that the Hamas–Israel war now is one which has its own internal logic, which might not be escalation, as I mentioned earlier, but might be more of a long-term inconclusive process of terribly humanly costly conflict that goes on for ages and ages: that’s what I mean by the logic of a situation.

By the logic of a situation, I mean something that can be tragic and can be malignant, as well as occasionally being something that has hopeful possibilities. In other words, history isn’t all random. Human judgments and decisions do produce situations that have a kind of built-in momentum, but it’s actually not very often that that’s benign.

GC: At one point you say that the undirectedness of evolution is a discovery of modern science. Now, as someone who has read Experience and Its Modes, you’re familiar with Oakeshott’s idea of presuppositions. So in my understanding of what’s going on here, it’s more a presupposition of modern evolution, that modern evolution said, let’s set aside the idea of teleology and see what we can get, and they’ve gotten a long ways. But I wonder what you’d say to that?

JG: Well, I think historically Oakeshott got the idea of presupposition, or was talking about it, at around about the same time R. G. Collingwood was. Collingwood was lecturing on that in the 1930s. You had a period in British intellectual life in Oxford and Cambridge in which Idealism, in the mode of Hegel, or F. H. Bradley by then, was still alive and was an attempt to analyze different modes of thinking—science, art, history—by reference to routine presuppositions. I suppose you could say, science, modern science at least, starts with the attempt to explain things in the natural world without invoking teleological presuppositions.

On the other hand, I take a more pragmatist approach to this, which is that if the non-teleological explanations are very successful, in the sense that they enable you to understand lots of things that happen and even predict certain things from time to time, then the older pattern of explanation just withers away. I think that is partly what has happened.

But what I’m really actually attacking in those passages in the book that you’ve quoted is an idea which is very common among many modern thinkers—many contemporary thinkers, including those who think of themselves as Darwinians—when they say, yes, Darwinism is a purposeless process, but we, we can now control it. And I first ask the question, how come something like free will or conscious control of evolution processes has emerged randomly? How did that happen? We need to explain that. But secondly, who’s we?

Here, although I’m not a Christian or monotheist, one of the great texts for me of the twentieth century—very short, very profound text—is C. S. Lewis’s Abolition of Man. And in The Abolition of Man, Lewis says when people talk about the power of man—humankind—over nature, what they’re really talking about is the power of some human beings over other human beings. And so there’s no “we,” and certainly if you’re a Darwinian there can’t be any “we.”

Hobbes thinks that humankind or the human species—as we would now say, the human animal—can’t do anything because it’s not an agent, just as tigers don’t go through the biological history of tigerhood trying to realize some “tiger project” or tiger essence. There are just lots of different tigers that come and go. Humans are the same, if you think of them in Darwinian, or indeed Hobbesian, terms. There’s no human agent doing anything. There’s no collective universal subject realizing itself through history; there’s just the multitudinous human animal made up of countless different ways of life and individuals, all of them containing many conflicting impulses and needs, gradually working themselves out in history separately.

I find this in, for example, Richard Dawkins, but also in Steven Pinker and others: here you have this random purposeless process of evolution going, but we are going to control it from now on. Well, two objections: there’s no human “we,” and secondly, in practice—this is Lewis’s point—“we” turns out to be a particular category or caste or group of human beings who aim to exercise power over other human beings to realize their goals or their objectives, regardless of the goals of these other human beings.

I think it’s a complete confusion, and one of the things I’m targeting in the book is this notion that if you’re a Darwinian naturalist then you will be a progressive or you’ll be a liberal. You won’t be anything—nothing follows from it actually. You may decide that there is such a meaningless and purposeless process. But you may conclude that actually the position of ethics is that this process should be curbed or prevented from assuming its most terrible and inhumane form. If, for example, it’s part of this process that some beautiful form of life or species or artifact be swept away, you might decide to resist the process, try to hold it back.

And that could equally be true if you think of it as operating in history: you might say, yes, the society that replaced Tibetan feudalism is more advanced, it’s more permeated by modern scientific knowledge and so forth, but it’s also more barbaric and more cruel and less civilized than the one that it replaced. That’s what I do say in the book because the Tibetan debates on Buddhism and metaphysics that were held in monasteries all across Tibet up until the 1950s—when they would be destroyed by the Chinese occupation—were an example of these monks almost playfully exploring and dialectically criticizing the foundations of their own civilization, but in a way which included respect for their opponents and subtlety in argument, and in a way which I think is highly civilized; whereas what now exists in much of the West, in many universities, an atmosphere of fear and persecution and the imposition of a crude dogma, is barbarism of a kind that is greatly inferior to what existed in Tibetan feudalism.

GC: I recently read That Hideous Strength for a second time, and I believe that it’s the fictional work-out of The Abolition of Man.

JG: What did you think of it?

GC: Very prescient.

JG: Well, he’s a very good writer. I wasn’t old enough to know him. But I knew someone who knew him well, in my college when I was at Oxford, a history teacher who was one of the Inklings who met with Tolkien and Lewis and Charles Williams and others. He told me a lot about Lewis, a very fertile and interesting writer. I think his three science fiction novels—if that’s what they were; they’re more like metaphysical novels, really, the last of which is That Hideous Strength, the second is Perelandra, and the first is Out of the Silent Planet—are really very great works of fiction, of metaphysical fiction, and there’s a lot to learn from that.

GC: I agree with you there. There’s plenty more we could talk about. But we’ve already run over our allotted time, and I’m out of the topics that I had jotted down for the interview. So I’d like to thank you for your time.

JG: I’d like to thank you for your interesting questions and your observations which have touched on aspects of my book and my work—and linked it with other thinkers like Oakeshott and Lewis—in a way that not many other people who’ve commented on the book have done. Great to talk to someone who knows what I mean when I refer to aspects of Oakeshott’s thought. There are areas where I disagree with Oakeshott—I think he’s too relativistic, I think that there is such a thing as human nature; that’s maybe one of the reasons that I’m more tolerant of Darwinism than a pure Oakeshottian would be—but he was a profound thinker.