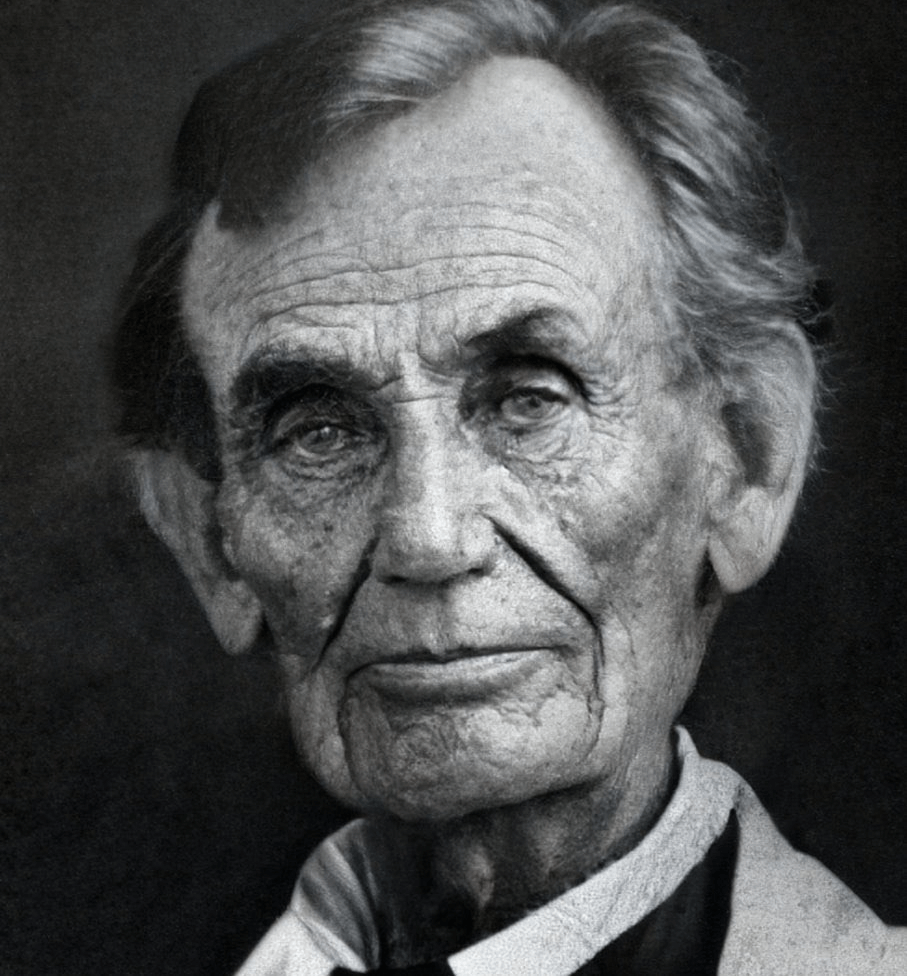

The new movie Here is a Forrest Gump reunion, featuring the director Robert Zemeckis and the actors Tom Hanks and Robin Wright. It’s a film about one particular place, in certain times, over all of time.

It might be the most Russell Kirk movie I have ever seen.

The entire film focuses on one plot of land, from the time of the dinosaurs and ice ages through the lives of Native Americans, the American Revolution, the Victorian era, the Roaring Twenties, The Beatles and Vietnam, the end of the last century and the beginning of this one. The lifespans of Richard Young (Hanks), his wife Margaret Young (Wright), and their family dominate most of the story, from the postwar era until today.

A hotshot pilot (Gwilym Lee) moves into the house with his wife when it is built in 1900. In the 1930s and ’40s, we see a pinup model (Ophelia Lovibond) living with her partner, an inventor (David Fynn). In the twenty-first century, we see a black family giving their teenage son “The Talk” (Nikki Amuka-Bird, Nicholas Pinnock, and Cache Vanderpuye). In centuries past, we see a Native American couple who lived on the land long before the house was built. All of these scenes happen interchangeably, with no discernible timeline. They also overlap: part of the screen might be continuing a scene from colonial times while the rest of the screen merges into the twentieth century.

Like Forrest Gump, Here is a journey through time with particular focus on the American experience, showing that human beings and the stories of their lives are similar in any age, in their relationships, families, loves, hates, joys, and struggles.

Time changes, the movie says. Human beings don’t.

Some critics have panned Here as being “soppy.” To be fair, some of it is. But critics said the same of Forrest Gump, which is now an American classic by any metric. In 1994, some critics also deemed Forrest Gump right-wing for its emphasis on family values. The critic Eric Kohn wrote (negatively) of Forrest Gump on the movie’s twenty-fifth anniversary, “‘Forrest Gump’ preaches conservatism in its bones, whether its creators intended it that way or not.” He had a point, just not in the way he meant it.

I don’t believe Here is as good as Forrest Gump, nor do I expect it to have the same pop culture prominence as the earlier movie. But I liked Here. The more I think about it, the more I like it, and its inherently conservative message is a primary reason.

“Redeeming the time.” “The permanent things.” These Kirkian concepts filled my mind while I watched the film. The entire concept of what the filmmakers were trying to execute seems deeply Kirkian.

Kirk’s conservatism was rooted in his love for the land, for his home, and the way these things shape people over time. He observed in The Politics of Prudence that “Continuity is the means of linking generation to generation; it matters as much for society as it does for the individual; without it, life is meaningless.”

Kirk also understood the central importance of the land we own and care for—the true leading role in Here. He wrote that “to be able to retain the fruits of one’s labor; to be able to see one’s work made permanent; to be able to bequeath one’s property to one’s posterity; to be able to rise from the natural condition of grinding poverty to the security of enduring accomplishment; to have something that is really one’s own” is of vital importance in building a meaningful life.

Place matters. So does inheritance. Change is inevitable. So is permanence. These are contradictions. They are also both true. Conservatives, Kirk believed, inherently understood this.

Here is about how this reality plays out over generations. It ponders why we’re here. To take just one example, Hanks’s character is a talented painter who gives up his passion and gets a conventional job to support his family after his teenage girlfriend becomes pregnant. They live in his parents’ home, which they eventually inherit in full. But his wife never feels like it truly belongs to them, and this causes a major rift between the couple. She wants more. He feels like he’s given up what he loves most out of a greater love for his family.

Should he have given up his painting? Or did he do the right thing? Should she be more gracious given their circumstances? Or does she have a point?

The filmgoer sees this all from a bird’s-eye view and can ponder accordingly, over a long period of time.

Here’s search for the lasting meaning in everyday life is profoundly Kirkian. “It is not by wealth or fame that you will be rewarded, but by eternal moments: those moments of existence in which, as T. S. Eliot put it, time and the timeless intersect,” Kirk wrote. “In such moments, you may discover the answer to that immemorial question, ‘What is all this?’”

That is ultimately the question this movie leaves to viewers, seeing many lives lived in one place for centuries, from a loving Native American couple centuries ago to a modern American couple wondering how their marriage went so wrong in a time closer to our own.

If progressives are forever trying to free man from earthly realities, Here shows what is permanent in the human condition. We all live through “eternal moments” where the “time and the timeless intersect”—where people’s lives overlap across lifetimes and centuries—even if we usually don’t notice them.

Here is about noticing them.