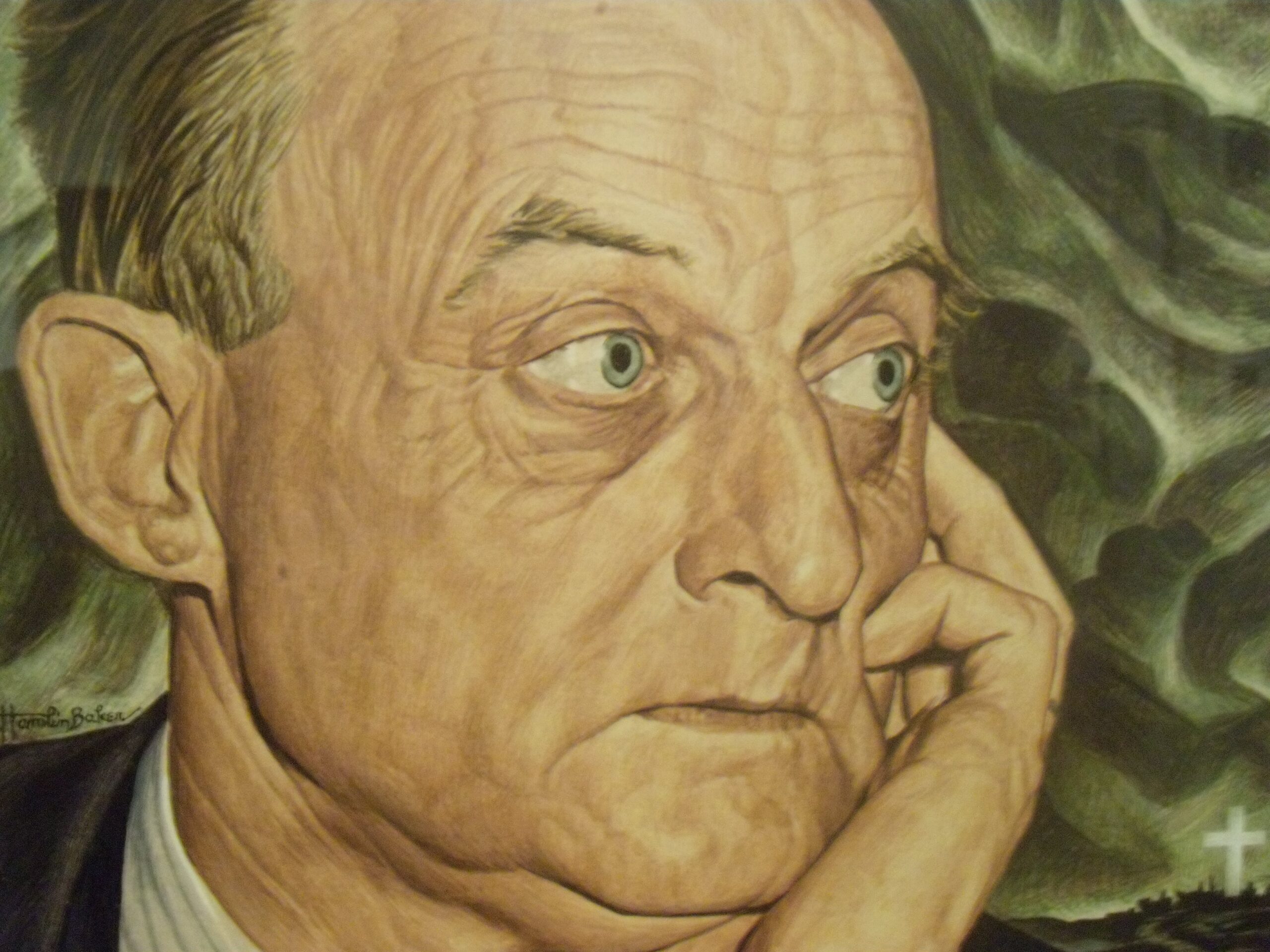

Irving Babbitt was the intellectual leader of the New Humanists. In a series of essays and books, including Literature and the American College (1908), Rousseau and Romanticism (1919), and Democracy and Leadership (1924), Babbitt applied his humanist philosophy to a variety of subjects—literature, higher education, politics, and religion. He influenced the other leaders of the movement—Paul Elmer More, Stuart Sherman, and Norman Foerster—as well as younger disciples who made the New Humanism a controversial movement by the end of the 1920s.

Babbitt was born in Dayton, Ohio. His father was a physician of eclectic intellectual interests, spiritualism among them, and would later represent to his son an example of the indiscriminate and facile sentimentalism that marked the modern age. The family moved frequently before Babbitt began his undergraduate career at Harvard University in 1885. There he met Paul Elmer More, the two being the only enrollees in a Sanskrit class. After travel in Europe, Babbitt began a teaching career at Harvard as professor of romance languages. He was an immensely popular teacher, known for his repertoire of ready quotations from great writers and thinkers. His students included Walter Lippmann, T. S. Eliot, Van Wyck Brooks, Foerster, and Sherman. Babbitt was generally unappreciated by his colleagues at the university, however. His defense of neoclassical standards in literature set him against more fashionable directions in literary criticism.

In the 1920s Babbitt’s influence grew steadily, and the New Humanist movement won a significant following, mostly in academic circles. In 1930, at the height of its influence, Norman Foerster published a collection of essays titled Humanism and America, to which Babbitt and others contributed and which became an intellectual manifesto of the movement. In the same year, C. Hartley Grattan summoned opponents of New Humanism to organize a counterattack called The Critique of Humanism.

Babbitt’s humanism defended a dualistic view of human nature, locating in it two opposing forces. On the one hand, human nature possesses an inherently expansionist instinct that seeks release from all constraints and pursues an indefinite liberation of will and imagination. But it also possesses a principle of control, a force for discipline and moderation. As paragon of the undisciplined romantic spirit, the French romantic Jean-Jacques Rousseau was, Babbitt believed, the major corrupting influence on modern culture. Babbitt always associated romanticism with the celebration of idiosyncrasy and the uniqueness of personality at the expense of a common human nature, especially as depicted in classical literature and its later emulations. Babbitt believed that romanticism had become endemic in modern life and culture, and he saw it reflected in the mindless cult of individuality that had deprived literature of any meaningful wholeness.

Babbitt also criticized the more recent influence of naturalism. Depicting man as the reflex agent of natural forces, this mode of understanding human nature, he believed, dissolved the principle of control and explained human behavior by reference to his race and environment. Romanticism and naturalism thus had reinforcing tendencies, depriving human experience of any center or universality. Babbitt further believed that these reinforcing effects were especially acute in the United States of his time. America, Babbitt said, had produced a culture that was both mechanistic, worshipping power and force, and at the same time sentimentalist and emotionally indulgent, as witnessed by the popularity of Hollywood movies and frivolous, romantic novels among the general public.

Over the course of his writing career, Babbitt artfully applied his dualism to a number of categories. The Masters of Modern French Criticism (1912) most fully outlines his literary theory, offering essays on Charles-Augustin Saint-Beuve, Joseph Joubert, and others. While he did not himself enter the “battle of the books” that raged after World War I (his followers, especially Sherman, took on the enemies of New Humanism, H. L. Mencken in particular), Babbitt opposed the new currents of impressionist criticism, with its emphasis on successful expression as the end of art, and historical criticism, with its efforts to explain art in terms of time, place, and environment. Both schools, he believed, made reductionist errors that deprived criticism of useful standards of judgment.

On the subject of education, Babbitt became an outspoken conservative critic of the elective system instituted by Charles William Eliot of Harvard in 1869. The issue symbolized the division between those who championed a broader curriculum in American colleges and those who wanted individual choice to weigh more heavily in students’ academic programs. Babbitt saw this direction as representative of the indulgent individualism of American culture and remarked that the modern college permitted unlearned youth to ignore the accumulated wisdom of the past in passing through an undergraduate program determined by individual whim.

In his views on society and politics, Babbitt was a conscious follower of Edmund Burke. He believed that modern politics had become essentially a contest between the “idyllic imagination” of Rousseau, which fostered utopian and egalitarian schemes of social salvation, and the “moral imagination” of Burke. For any society, the primary challenge was to grasp by imagination and symbol the enduring tradition joining past to present. Against the democratic tendencies by which people meet at a low commonality, Babbitt urged that individuals discover their common higher selves as defined by historical memory and tradition. Babbitt criticized the excesses of democracy, deplored socialistic reforms, and championed the rights of property. But he argued also that American society could not find its necessary leadership class among the reigning, vulgar plutocracy.

The New Humanists disagreed on the subject of religion. Some adhered to principles founded in divine inspiration or supernatural authority; others called for an empirical humanism. Babbitt liked to say that he wanted to meet the moderns on their own grounds. His defense of humanism’s “first principles” was made without appeal to supernatural sanctions. He defined humanism and religion as natural allies and even acknowledged a certain dependency of humanism on religious insight, but in an age of materialism and secularism a humanistic recovery, he believed, could be secured only by a strict account of human experience itself.

Babbitt was a major American voice of classic conservatism in the tradition of Burke. His dualistic philosophy was simple in outline but gained richness of insight and application in Babbitt’s more mature works. In the years after his death, Babbitt’s following grew and included some significant conservative thinkers, among them Russell Kirk, Peter Viereck, and George Will.

Further Reading

J. David Hoeveler, Jr., The New Humanism: A Critique of Modern America, 1900-1940

Frederick Manchester and Odell Shepard, Irving Babbitt: Man and Teacher

Thomas R. Nevin, Irving Babbitt: An Intellectual Study

George A. Panichas, The Critical Legacy of Irving Babbitt: An Appreciation

George A. Panichas and Claes G. Ryn, Irving Babbitt in Our Time

Claes G. Ryn, Will, Imagination and Reason: Irving Babbitt and the Problem of Reality

This entry was originally published in American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia, p. 54.