There are different kinds of gifts, but the same Spirit distributes them. There are different kinds of service, but the same Lord. There are different kinds of working, but in all of them and in everyone it is the same God at work.

Now to each one the manifestation of the Spirit is given for the common good. To one there is given through the Spirit a message of wisdom, to another a message of knowledge by means of the same Spirit, to another faith by the same Spirit, to another gifts of healing by that one Spirit, to another miraculous powers, to another prophecy, to another distinguishing between spirits, to another speaking in different kinds of tongues, and to still another the interpretation of tongues. All these are the work of one and the same Spirit, and he distributes them to each one, just as he determines.

—1 Corinthians 12

Many conservatives have objected strongly to the spate of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives undertaken by many schools, corporations, and government agencies over the last decade. Elon Musk recently claimed that “DEI means people DIE.” President Trump recently changed government hiring practices to focus only on merit, and eliminate equity as a hiring criterion.

While many of conservatives’ complaints about these programs have merit, I will argue that is easy to overstate the case against diversity. For instance, the writer and filmmaker Matt Walsh tweeted, “Diversity in and of itself has never improved a single institution in the entire history of human civilization.”

Is Walsh’s claim correct? It can be tempting to resolve the tension between a desire for unity or diversity by simply choosing one side over the other. Quite obviously, the DEI initiatives of the last decade have been all in for diversity, giving us slogans like “diversity is our strength.” In an understandable but mistaken reaction, many conservatives now disdain diversity and praise unity.

But a one-sided focus on unity is as faulty as a one-sided focus on diversity. Strength in countries and institutions comes from a balance between diversity and unity, and this principle is applicable at many scales.

We can begin at a very small scale, where we now know that cells, once thought to be the smallest living units, actually contain great internal diversity. But, of course, cells cannot tolerate too much diversity and so have cell membranes to keep out unwanted material.

A one-sided focus on unity is as faulty as a one-sided focus on diversity.

Or consider that the human body does not consist of seventy-eight hearts, or seventy-eight brains, or seventy-eight spleens, but of seventy-eight or so different organs, only a handful of which are duplicates of another organ. St. Paul asked, “If they were all one part, where would the body be?”

Nevertheless, this in no way means that increasing internal diversity is always good for the organism. For instance, transplanting a goat’s liver into a human being would certainly increase the diversity of that human’s body, but in a way that would be fatal to the donee. Even a transfusion of the wrong type of human blood—once again, a clear increase in diversity—can be fatal to the recipient. There must be a unity within the diversity of a living organism.

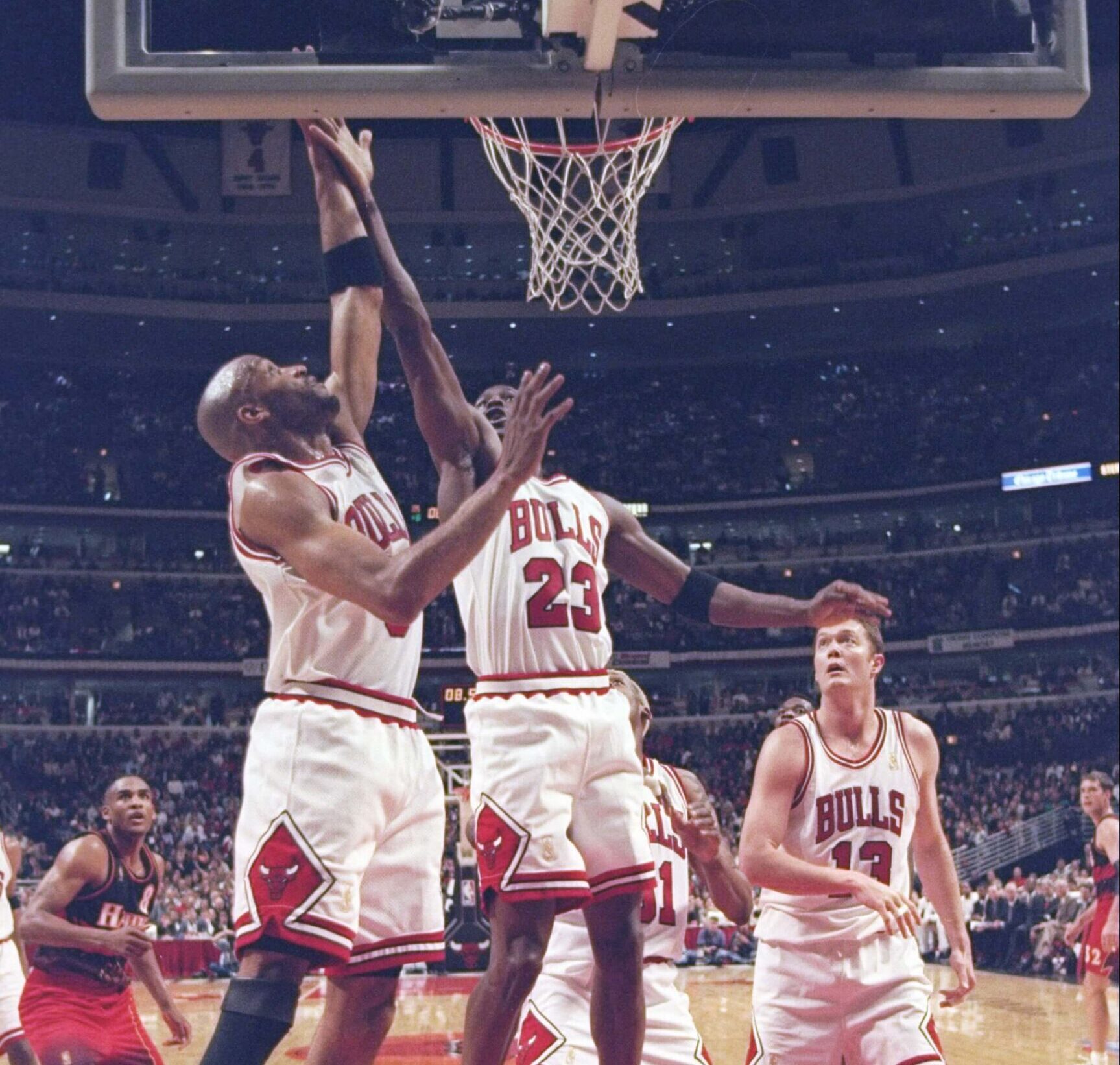

Moving to a slightly larger scale, let us regard an outstanding basketball team. No team in recent decades has been as successful as the Chicago Bulls of the 1990s. The 1995–96 team, perhaps their best team of that era, featured, of course, Michael Jordan, one of the greatest scorers of all time. But he only won accompanied by a diverse cast of complementary players, such as Scottie Pippen, a versatile second scoring option and tremendous defender; Dennis Rodman, the league leader in rebounds; and Steve Kerr, a 51.5 percent three-point shooter.

So is it diversity for the win here? Hardly. First of all, one diverse element the Bulls did not include on their roster was bad basketball players. Or even mediocre basketball players. Furthermore, to become champions, the team had to achieve a high degree of unity in their main goal: winning games. Imagine, if you will, the same players assembled, but with Jordan most interested in showing fans what sneakers he was wearing, Pippen focused on showing he was better than Jordan, Rodman interested in the game as performance art, and Kerr trying to demonstrate that he could be a great head coach in the future. And they also were largely united in their willingness to be guided by their brilliant coach, Phil Jackson.

At a similar scale, a great musical group does not have four or five identical musicians. The Beatles would not have been what they were if they had consisted of four Harrisons, or four Lennons, or four McCartneys, or four Starrs. Nevertheless, to succeed, these four quite different musicians had to spend thousands of hours forging a common identity playing in English and German clubs before they became the world’s most successful band.

Moving up in scale again, a city without a diverse economic base is at great risk of ruin, as documented by, for instance, Jane Jacobs, in her book The Nature of Economies. Here Detroit is a paradigmatic example: reliant almost entirely on the automobile industry, when car manufacturing moved away from the city, it underwent a catastrophic decline.

But once again, that does not mean that a one-sided emphasis on diversity is a recipe for urban flourishing. If the citizens of a city do not feel that they share a common bond as citizens, the city is likely to descend into internecine strife. We may take the recent decades of violence in Belfast or Beirut as cautionary examples here.

Expanding our vista yet again, ecosystems also offer evidence that a balance between diversity and unity characterizes healthy systems. As documented by James C. Scott (in Seeing Like a State) and many others, monocropping a forest or a farm exposes that ecosystem to extreme risk for complete wipeout by a new pathogen. A forest consisting entirely of one species of tree is not a healthy forest.

Yet that does not mean that we should always increase the diversity of every ecosystem without bound. Invasive species are the most obvious example of why we should not do so. In my own area of the American south, kudzu and fire ants are examples of introduced diversity that have been extremely harmful to the local ecosystem. Of course, a big problem here is that invasive species may reduce the diversity of an ecosystem over time. But clearly, at the point when they are introduced, they add diversity.

“That is all well and good,” my reader may protest, “but you know that when people talk about diversity today, they mean almost entirely racial, ethnic, and sexual diversity.” And in fact, a very sound complaint people lodge against the diversity movement is that diversity in ideas is often squashed in order to achieve diversity in these other factors. “So what do all of your points above have to do with, say, having racial diversity in an organization?”

While the DEI movement has suffered from a one-sided emphasis on diversity, like any ideological movement, it would not have had any success without some elements of truth in their case to make it plausible. If, for instance, our elite educational institutions came to have student bodies consisting almost entirely of Asian and white students, would this really be a salutary outcome? For one thing, the diversity advocates are correct in claiming that exposure to people of different backgrounds than one’s own is, in itself, educational. It is also true that some people’s true academic ability has been hidden beneath a midden of unfortunate socioeconomic circumstances—both in black and Hispanic communities and poor, rural, white communities as well. But perhaps most importantly, when certain highly prestigious institutions are seen as the exclusive domain of only certain segments of our society, the organic unity of our society as a whole is disrupted.

Given that the actual balance between diversity and unity that will result in a healthy system varies from case to case, one conclusion we might reach is that one-size-fits-all rules constraining this balance in one direction or another are likely to do more harm than good. Why not, for instance, let one organization go as far as it likes in seeking racial diversity, while allowing another one to take on new members purely based upon test scores or degrees earned, and yet another to hire or admit whomever it wants for any reason at all? Then let the results they achieve speak for their approaches. This would return America to our earlier understanding of freedom of association.

The United States, after all, has a balance between diversity and unity written right into our constitution: it is called federalism, with a diverse group of states united into one federation. This admirable balance should be our guide in the DEI debate, which is on a deep level about how individuals and groups relate to each other as Americans, and as human beings.