In my mid-twenties, I found myself at a crossroads. Down one path, if I stayed the course as a graduate student in political science, I could pursue a life in academia. Down another path, I could go back to my hometown in Washington state to challenge an eight-year incumbent for a swing-district legislative seat. I chose the latter and won that election by a mere twenty-nine votes out of fifty-two thousand cast. Every vote matters! Over the next dozen years I spent in public service—as a member of the State House and Senate and then my county legislative body—I probably learned more about politics than I would have if I had stayed the course in that political science Ph.D. program.

I found political life thrilling. Every day was an opportunity to learn something new, and the subjects to be explored were wide-ranging.

Early on in my legislative service, I began to record the lessons that I was learning from all kinds of people: constituents, colleagues, staff members, lobbyists, and state agency people. The bit of wisdom that seemed to stand out the most came from a former legislator who told me, “Relationships are more important than policies.” Another person who had held statewide office said, “Whatever else you do in the legislature, always respect the institution. It is bigger than any one issue or agenda.”

Another former legislator encouraged me with two words: “Be yourself.” A colleague advised me to “Smile often.” Another pointed to the aisle in the middle of the House chamber and declared, “That’s where the real work gets done, right there when you’re crossing the aisle.” And finally, a veteran legislator advised me, “Never get too comfortable in public office.”

As far as I was concerned, I was just as much a student of political wisdom as if I had stayed in my Ph.D. program.

Political wisdom is undoubtedly what many students are seeking when they choose to major in political science, public policy, or public administration. Yet as fields of study, political science and related disciplines pay relatively little attention to the practical wisdom that is needed for governing, much less the philosophical and ethical foundations for that service. Students seeking a solid education in democratic statesmanship—citizen leadership in a free society—must supplement their classroom studies of politics or look elsewhere altogether.

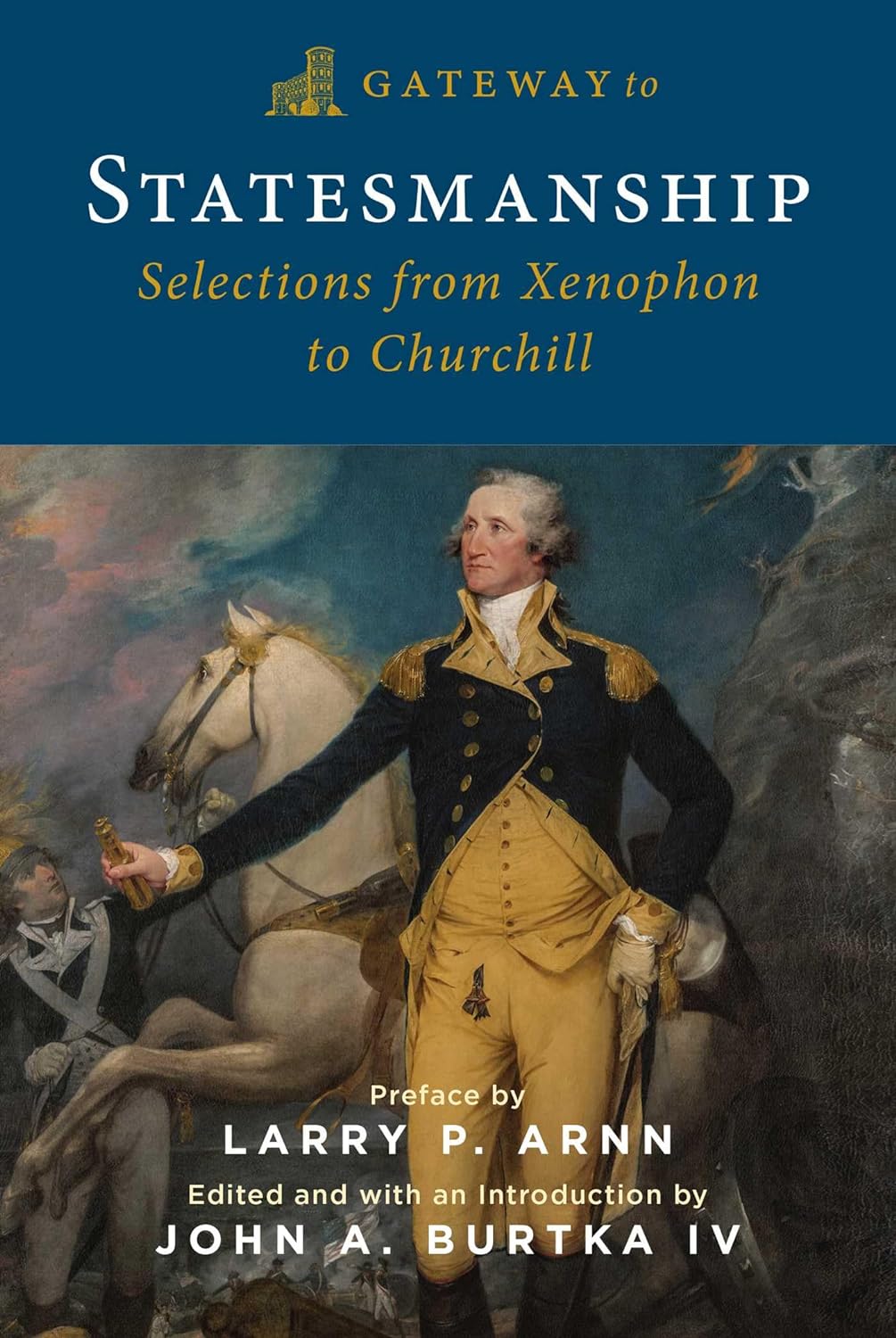

Fortunately, John A. Burtka IV has compiled a remarkable collection of some of the world’s greatest political wisdom in Gateway to Statesmanship: Selections from Xenophon to Churchill. Burtka, the president of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, highlights a tradition of advice provided to kings and other rulers known as “mirrors for princes.” Much of the mirrors-for-princes genre is the product of philosophers who came to advise kings, while a good deal of it also consists of kings and other leaders recording their own advice and reflections.

While this tradition may at first seem like an ancient relic, an artifact from monarchies past, Burtka defends it as “a universal phenomenon that spans all races, creeds, and geographic locations.” In addition to Western writers, the anthology includes non-Westerners such as the ancient Indian polymath Kautilya; the third-century BC Chinese philosopher Han Fei, who commended persuasion as a key skill over compulsion; and the Syrian thinker Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi, who wrote in the eighth or ninth century AD about ethical leadership, the importance of a ruler’s physical and intellectual competencies, and the utility of a dispersed governance model.

What role does mirrors-for-princes writing play in a self-governing society, where statesmen and stateswomen are elevated by their fellow citizens? It is appropriate that George Washington’s image is featured on the cover of Gateway to Statesmanship, for Washington knew well the importance of forming leaders. In his first State of the Union message to Congress and in subsequent addresses, Washington urged a strong emphasis on civic education for citizen leaders.

Burtka points to the role of the Constitution in shaping and dispersing leadership in the American republic: “The ‘institutional constitution,’ operating by the consent of the citizenry, replaced the ‘institutional individual’ (that is, the monarch) as the lead actor on the political stage of America and, eventually, throughout most of the Western world.”

It is worth noting, however, that many of the insights that led to the framing of America’s constitutional republic, with its emphasis on self-rule, limitations on centralized power, and institutional checks and balances, surfaced in advice to rulers of other regimes through the ages. For example, Xenophon wrote in his Education of Cyrus in the fourth century BC, “Men unite against none so readily as against those whom they see attempting to rule over them.” And Thomas More wrote of the need to avoid heavy-handed government.

Burtka’s book could well serve as a “gateway” to a renewal of widespread study, writing, and discussion about republican leadership and statesmanship.

A passage selected from Theodore Roosevelt is indicative of the distinguishing characteristics of citizen leadership in a republic from the role of rulers in monarchical societies: “Under other forms of government, under the rule of one man or very few men, the quality of the leaders is all-important . . . But with you and us the case is different. . . . in the long run, success or failure will be conditioned upon the way in which the average man, the average woman, does his or her duty, first in the ordinary, everyday affairs of life, and next in those great occasional crises which call for heroic virtues. The average citizen must be a good citizen if our republics are to succeed.”

The sustainability of a free society depends fundamentally, then, on the civic character of everyday people, who may be called upon to serve in extraordinary ways.

Even though statesmanship in constitutional America takes a very different form than it did in monarchical societies of the past, there is still much that can be learned from leaders, philosophers, and observers of earlier eras. According to Burtka, “The relationship between a great mentor and great leader spans time, stretching across the centuries through the written word, equipping each new generation of leaders with the education necessary to become great themselves.” From these mentoring sages, we can learn virtues like public-spiritedness and practical wisdom, or prudence.

True to its title, Burtka’s book could well serve as a “gateway” to a renewal of widespread study, writing, and discussion about republican leadership and statesmanship: “We should not hesitate to write our own mirrors-for-presidents that draw from our unique American tradition and elevate the standards for contemporary leaders,” Burtka says. And statesmanship is not just for political leaders. The lessons of the mirrors-for-princes tradition may also prove useful to leaders in other walks of life, including “the CEO, the entrepreneur, the student body president, the captain of a sports team, and anyone striving to become a ‘prince’ in his or her particular domain,” as Burtka writes.

As Erasmus wrote, “The main hope of getting a good prince hangs on his proper education.” And according to Erasmus, a rightful tutelage for kings includes instruction in civic friendship, the geography of the place they rule, enlightened patriotism, and the arts of liberty and limited government. If these are suitable subjects of attention for a monarch, they are just as fitting for a citizen in a constitutional democracy. Burtka’s timely book is a wonderful place for students of political wisdom to begin their studies.