T . S. Eliot remarks in his essay on “Seneca in Elizabethan Translation” that “Few things that can happen to a nation are more important than the invention of a new form of verse.” That poetry is always relevant to the larger concerns of society is a truism which has been remarked on from the time of Plato to Bob Dylan. Jacques Barzun observed that it was impossible to understand German romantic political theory unless one set it to music. But whatever the power of music as an aid to cultural understanding, I believe it is easily demonstrable that we moderns cannot know ourselves unless and until we have read the poets. Poetry is always relevant.

But in what sense is poetry relevant? Poets, it seems to me, fall, not easily but with some pushing and shoving, into two categories. The greatest poets are those who speak of the permanent things, those whose rhetoric crystalizes and defines the perennial human condition and delineates those things which from generation to generation and across the gulf of differing and estranged cultures are perceived by all mankind to need utterance. Then body and soul together are touched and the poet speaks for all mankind what we, had we been able to formulate our incoherent thoughts, would have said. The poet is mankind’s better and more articulate self.

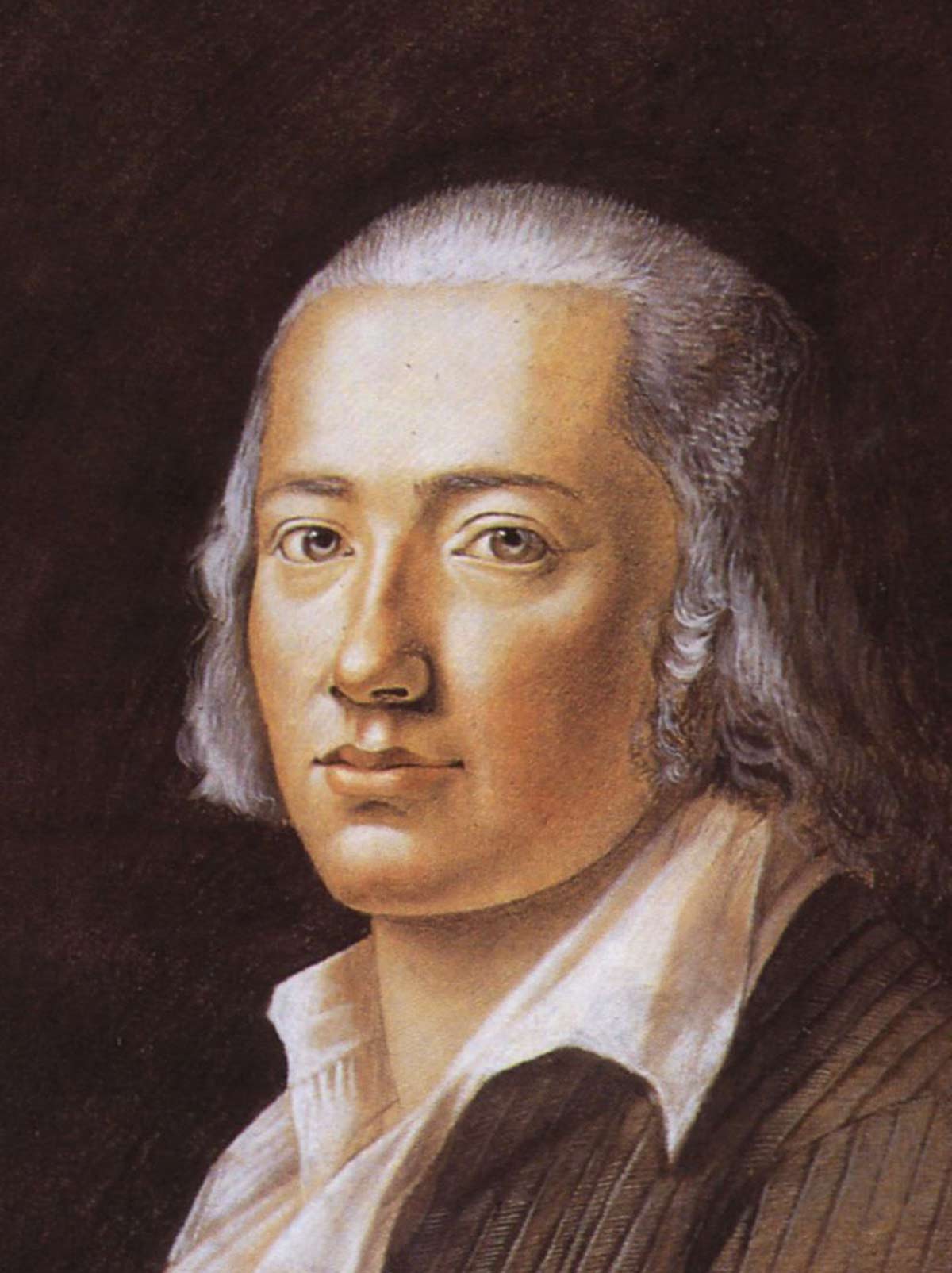

However, most of the poetry of the past two centuries has not been a poetry of universal human relevance. It is the poetry of a particular age, of a particular moment in time. However great The Wasteland is as poetry, however deeply it spoke to my generation, its preoccupations and its symbols are not such as will carry it to a wide audience a century hence. Romanticism, which was so preoccupied with time and the historistic quality of human experience created a poetry which more than any other is bound to a moment or an era. The relevance of the poetry of the Romantics lies in its ability to crystalize a moment, to identify the yearning and the aspirations of an era, to encapsulate the metaphysical anxieties and the quest for a subjective but intense realm of personal experience. The universal is replaced by the infinite and the Greeks, made over in the image of an alienated and irrational generation, demonstrated how even the certainties of classical humanism were forced to bow before the style of a new generation. Hölderlin was among the first and was perhaps the greatest to perceive the poet’s mission as personal and time-contingent utterance rather than universal statement. In the 1840s when asked for a poem he replied, “As Your Holiness commands. Shall it be about the spring, or Greece, or the spirit of the age?” But, in fact, Hölderlin wrote about little other than the “Spirit of the age”; the spirit of the age as it was embodied in his own experience. We of course rarely share Hölderlin’s experience but we share his intellectual world and that fact makes him our contemporary.

Here I do not wish to imply that the elements of contemporaneity in Hölderlin were those elements which are commonly listed in descriptions of pre-romanticism and romanticism. To be sure, Hölderlin had, as had Herder, come to equate the conceptions of Kind, Naturmensch, Volk and Urpoesie. Indeed Hölderlin’s poems return to these themes and equivalences time and time again. Every thought and attitude in contemporary society is colored by what A. O. Lovejoy described as the metaphysical pathos which clusters around these conceptions.

Nor is the organismic conception of nature the great bridge between the poetry of Hölderlin and the sensibility of the present. Certainly Hölderlin merges the cosmic process, the environment and the individual into one differentiated but unitary consciousness. His successors have hardly equaled the keenness of his perceptions in this respect and not even the symbolists were capable of making language a more evocative instrument for the purpose of getting behind the phenomena of nature to its intrinsic spirit. The spiritualization of nature is, after all, one of the commonplaces of the romantic mood.

Modernity is an art without boundaries; subject and object are one; poet and reader are united, environment and organism merge and, most importantly, creator and creature are indistinguishable.

The emphasis upon the singularity of place in the life of the individual and the race, implicit even in the Swabian vocabulary of Hölderlin, is not ultimately the element which binds him to our own time as a contemporary. Ethnicity, localism, the landscape of a particular place and a poetic vocabulary which echoes a provincial vocabulary are to be found in varying degrees among all the romantics. Local color is the easy passport into the sentimentalized landscape of the romantic poet and painter.

Those who have sought to account for the strong romantic emphasis in the thematic materials and symbolic universe which Hölderlin employs have emphasized the impact of Pietism and particularly the Pietism of the Swabian school. No doubt Kostlii, Bengel, Oetinger and Hahn were enormously influential and did much to tie Hölderlin to the world of the romantics and pre-romantics. Still the Pietistic element in his poetry, if anything, estranges us rather than makes us contemporaries. Much the same thing must be said of the world of German idealistic philosophy which impinged so dramatically on the personality of Hölderlin in the form of his youthful friendship with Hegel and Schelling. They were able, taken together with the influence of Schiller and Goethe, to carry Hölderlin into the world of romanticism but all of them would have been unable to make Hölderlin our contemporary. However closely related to the modern sensibility those conceptions are they are not of the essence and they are, finally, not what Hölderlin is all about. None of them will give us the key to Hölderlin’s tormented and tragic world and none of them will provide us with an explanation of Hölderlin’s insight into our own frightening predicament.

Alienation has become a cant word, but then intellectual history is littered with cant words such as nature, grace, justification, rationality and order. And no other word will serve to indicate the precise point of connection between ourselves and Hölderlin. Time and again Hölderlin says, “let us have done with man as he is; let us have done with things as they are and put on a new and more perfect humanity; live in a new and more perfect world.” Hölderlin’s Greece is not to be confused with the Greece of antiquity. It is Utopia; a historicist utopia, to be sure, rather than a utopia of the future but it is utopia, nonetheless. It is a symbol of estrangement and alienation overcome, of harmony restored, of ecstasy regained. It is, to employ the much-used phrase of Eric Voegelin, an immatization of the eschaton and that it is identified with the unattainable past makes the poet’s yearning all the more poignant and the poet’s pessimism and frustration all the deeper. Schiller and Goethe were correct in their skepticism of Hölderlin’s classicism. Hölderlin’s gods have as little to do with the Greeks as Nietzsche’s Zarathustra has to do with Iranian religion.

But alienation from what? Not surely alienation from God, that fall from grace and estrangement which is the consequence of sin. Hölderlin’s estrangement is not from human nature as it was or as it is but rather an estrangement from human nature as it might be. That is the key to the philosophies of radical and revolutionary transformation which have been such an important element in the contemporary world. It is in terms of this alienation that we can understand the element of Streben which was so essential a feature of romantic poetry and art and so intrinsic an element in the modern sensibility. It is alienation, too, which makes understandable the romantic preoccupation with the infinite, the romantic flight from closed systems and limited universes. The romantic painters, particularly Caspar David Friedrich, symbolized that unknown and mysterious infinitude by a figure at a window or peering out into some other vastness which cannot be glimpsed by the beholder of the picture.

Infinitude, however, is always associated by Hölderlin and by ourselves with the infinite deeps and vastnesses of the personality and the consciousness. The description of the landscape tends to abstractness and is usually, with the exception of the poet, unpeopled. The poet’s vision is interior even though he symbolizes his search by depicting an exterior reality. Moreover, there is always a beyond, an ever receding horizon, an unattainable distance. Nor can it be said that Hölderlin’s imagery is sensuous. It is intellectual rather than sensate. There is a constant calling for intensity, a frenzied movement toward the ecstatic but these elevated states involve a mystical estrangement from the here and now.

The syntactical peculiarities of Hölderlin’s poetry are not aesthetic accidents or affectations. Hölderlin was a self-conscious artist and his innovations point the way to the new structure of art and poetry. The artist in the modern period has attempted to break the power of the observer and the reader to objectify experience. The movement in modern poetry has been one from observation to participation and the purpose of Hölderlin’s syntactical experiments is involvement and immediacy. Hölderlin’s poetry abolishes the spectator, the neutral observer. Indeed, the poet not only engulfs and subjectifies the landscape but he absorbs the other completely so that the reader becomes an aspect of the poet’s projected selfhood. To this end Hölderlin does not describe or depict, he incites. Hölderlin’s syntax leads the reader not only inside the poem and the meaning of the poem but inside the poet. The affinities between Hölderlin and Hopkins or Joyce in this respect are all too clear.

Modernity is an art without boundaries; subject and object are one; poet and reader are united, environment and organism merge and, most importantly, creator and creature are indistinguishable. The great revolutionaries in romantic poetry and philosophy tended to begin their careers in theology. They were, from Hölderlin and Hegel to Nietzsche and Joyce, spoiled priests and stikkit ministers. That distinction between the divine and the mortal which was so completely a part of the Greek consciousness was expunged by the poets and philosophers of romanticism. Perhaps that is the single most important characteristic of modernity. It was the effort of the romantic poet and philosopher to elevate man to the stature of the deity.

I do not wish at this point to detail Hölderlin’s theology, if indeed one can call it a theology. Romano Guardini in his Hölderlin, Weltbild und Frömmigkeit has explored that subject in detail, though I believe Guardini’s work insufficiently critical and colored by the same romantic subjectivism and lack of distance which characterize Hölderlin’s poetry. It is clear, however, that Hölderlin believed himself to be living at a decisive moment in history. It is a moment of longing and anxiety. The catastrophe which will usher in the new age is at hand and Hölderlin casts himself in the role of the apocalyptic prophet. As Guardini makes clear, this attitude of expectation and the certainty that a new age was at hand is shared by Hölderlin and Nietzsche. It has been shared by moderns generally. Eschatological anxiety is the mark of the present era. What Guardini did not realize was that even in Hölderlin’s day both Christian and Gnostic eschatologies were current and popular and that the turn of the century, the revolution and the collapse of the empire, all led men to anticipate a decisive break in the cycle of the ages. That break implied not only a new cycle of history but a transformed and renewed humanity. Hölderlinian, Hegelian, Marxist and Nietzschean anticipations all insisted upon an end to alienation.

Even more contemporary, however, was the conception held by Hölderlin that the way to wholeness was not through ethical transformation but rather through aesthetic experience. Men became like gods through the exercise of their creative potentialities.

Then welcome, O silence of the world of shades!

Contented I shall be, even if my lyre does not accompany me on that downward journey;

Once I lived as the gods live, and that suffices.

The creative act, even in politics, is modeled on the work of art, and aesthetics replaces metaphysics and theology throughout the whole of our era. Until Nietzsche, the reason why this should be the case was unclear. It was Nietzsche who perceived that in a world in which order has been dissolved in anarchic chaos only the arbitrary order of art or of violence is possible. (Our own generation has come to see that in a world without order the order of art and the order of violence are equivalents.)

That development in the human spirit still lay in the future, however. For Hölderlin the act by which the human raised itself to the stature of divinity was the creative gesture. Religion and morality are swallowed up in aesthetics and men transcend their creaturely and human limitations by turning their lives into a work of art. It is, I believe, mistaken to conceive of Hölderlin’s gods as numinous forces or religious entities as does Guardini. They are, in fact, the transcendent spirit of art; they are what man might become were he able to purge himself of the dross of the mundane. Art had, in fact, become the great religious surrogate of Western society and remained such until it was replaced by violence.

But note that the creative act, that life as art, is not the consequence of rational analysis. Rather it is a state of consciousness in which the spirit or the soul projects on the world of existential reality the forms which it has discovered at the deepest level of its experience. It is for this reason that the Dionysian and the unconscious have played such an inordinantly large role in contemporary culture. Here, as in other areas, Hölderlin was a prophetic voice. Here, as in so many other areas, Hölderlin anticipated Nietzsche by fifty years.

But consciousness is not method, is not analysis, and it is for this reason that both Hölderlin and Nietzsche verge so often on sentimentality. It is for this reason that poets, musicians, painters and philosophers who belong to the romantic school but who do not share the consummate artistry of Hölderlin and Nietzsche lapse so often into sentimentality and bathos. Die Wiederkunft des Dionysos, that creative aesthetic state out of which men and their culture were to regenerate and recreate themselves, too often bore the stigmata of madness or the triviality of silliness and sentimentality. In all of these respects Hölderlin traveled the road of our culture ahead of us.

But Hölderlin and Nietzsche found Dionysos and Christ in an antithetical relationship. For both the new age was to be an age under the sign of Dionysos. Still Christ would not die. Christianity is one of those historical experiences which absolutely transforms history. Willy-nilly all those who come after that historical experience are in some sense Christian. Certainly a return to a pre-Christian state is impossible. One can graft Aristotle on to Christianity; it is quite impossible to graft Christianity on to Aristotle. Hölderlin and after him Nietzsche, discovered that history is a one-way street, that time’s arrow moves unidirectionally. When Pan died at the beginning of the Christian era his morbidity was quite complete and no amount of resurrectionism by intellectuals living in what they believe is a post-Christian era is capable of reviving him. Is it possible that both Hölderlin and Nietzsche broke themselves on this stumbling block?

However unsuccessful Hölderlin and Nietzsche were in reviving Dionysos they both anticipate and pave the way for a mood which had its equivalent in the ancient world. When E. R. Dodds concluded his study of The Greeks and the Irrational he said:

in writing these chapters, and especially this last one, I have had our own situation constantly in mind. We too have witnessed the slow disintegration of an inherited conglomerate, starting among the educated class but now affecting the masses almost everywhere, yet still very far from complete. We too have experienced a great age of rationalism, marked by scientific advances beyond anything that earlier times had thought possible, and confronting mankind with the prospect of a society more open than any it has ever known. And in the last forty years we have also experienced something else—the unmistakable recoil from that prospect. It would appear that, in the words used recently by Andre Malraux, “Western civilization has begun to doubt its own credentials.”

What is the meaning of this recoil, this doubt? Is it the hesitation before the jump, or the beginning of a panic flight? I do not know. On such a matter a simple professor of Greek is in no position to offer an opinion. But he can do one thing. He can remind his readers that once before a civilized people rode to this jump—rode to it and refused it. And he can beg them to examine all the circumstances of that refusal.

Was it the horse that refused or the rider? That is really the crucial question. Personally I believe it was the horse—in other words, those irrational elements in human nature.

Nothing I might add could speak more clearly of the contemporarity of Hölderlin or link him more completely to the world of his beloved Greeks.

Stephen Tonsor was an author and a professor of history at the University of Michigan.