Rare indeed is the publisher so possessed of acumen, audacity, and a sense of mission that he is willing, even eager, to flout the temper of the times. Such an intrepid popularizer was Henry Regnery, publisher of two of the most influential conservative books of the mid-twentieth century: God and Man at Yale, by William F. Buckley Jr., and The Conservative Mind, by Russell Kirk.

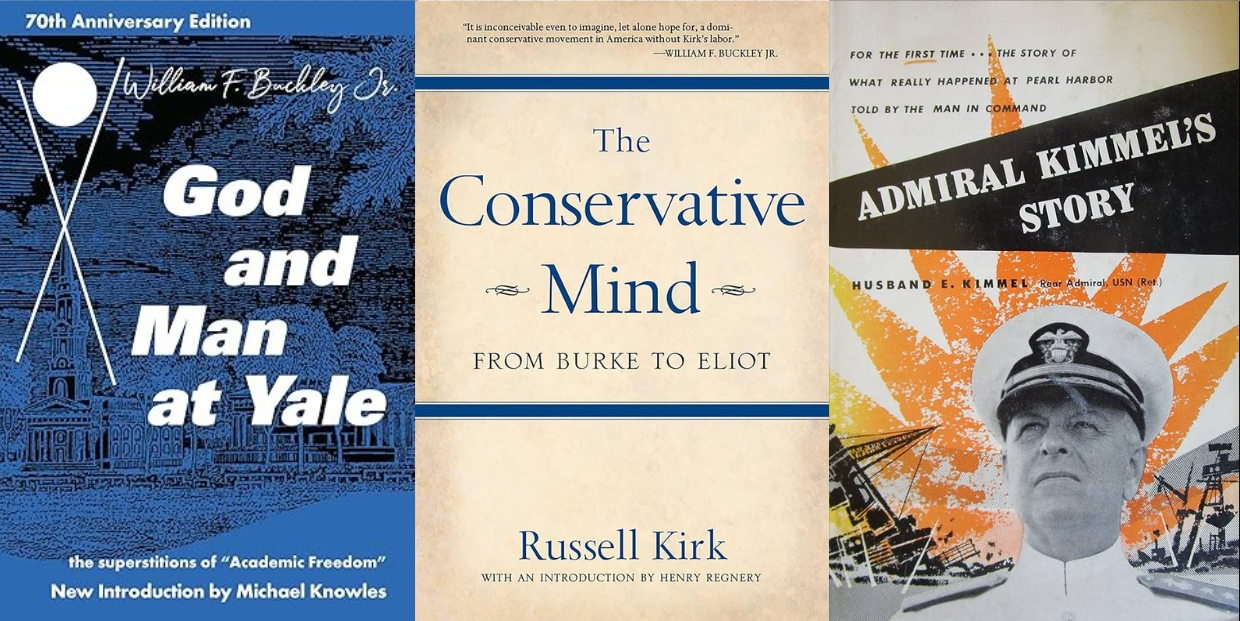

By the 1950s, Regnery explains, Albert J. Nock, T. S. Eliot, Richard Weaver, Eliseo Vivas, and other conservatives had produced a substantial body of criticism of liberalism. What was lacking was a work that gave coherence and identity to conservatism. “It was the great achievement of Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind,” Regnery writes, that it provided “a unifying concept.” It offered convincing evidence that not only was conservatism an honorable and intellectually respectable position, “it was an integral part of the American tradition.” It might be too much, Regnery conceded, to say that “the postwar conservative movement began with the publication of The Conservative Mind, but it was this book that gave [the conservative movement] its name and, more important, coherence.”

“The firm I founded was born in opposition,” Regnery writes in his memoirs, and so it remained under his direction from the late 1940s until the 1970s. By opposing the liberal establishment that controlled most of America’s political and intellectual life, says Regnery, “We contributed substantially to the development of the modern conservative movement.” That is too modest a judgment given Henry Regnery Company’s launch of Buckley and Kirk as well as its publication of the works of such prominent conservatives as Whittaker Chambers, John Dos Passos, Freda Utley, Frank Meyer, and James Burnham. The Regnery Company was called “controversial” by the establishment, explains Regnery, because its books were “consciously in accord with the traditional values of Western civilization.”

Henry Regnery was born in 1912 in Chicago, Illinois, the son of a successful textile manufacturer of German Catholic background. His mother was of English and Welsh descent, and her father had served in the Union Army during the Civil War. Highly successful, Regnery senior was an unusual businessman, “modest, unassuming, and generous,” who did not regard money as an end in itself. Henry’s mother had a strong personality with definite opinions, particularly about behavior. But “our household,” Regnery writes, “revolved around my father,” who had a great selection of books. While in high school, “I went through much of Dickens, Stevenson, and Mark Twain.”

After high school, he went to a Chicago technical school to study mechanical engineering and then math at MIT. Though he never became an engineer, he learned “something about three of the most influential forces of our time: science, technology, and organized social uplift—enough to regard them all with skepticism.” Music was always a passion of his. While studying at MIT and later economics at Harvard, he took cello lessons at the New England Conservatory, listened to the Boston Symphony every week, played in the MIT orchestra, and read widely, learning enough about history to know that “civilization had not begun with the steam engine and to appreciate the role of order in affairs.” His professor in economic history at Harvard was the famed Joseph Schumpeter, who was once asked by a student which economic system was most desirable. Schumpeter replied: “It all depends on what you want. If I had the choice, I would take the society that produced the cathedral at Chartres.”

Regnery arrived at Harvard an admirer of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, but began to change his mind because of the left-leaning students and bureaucrats whom he met and because he was learning about the realities of the world from Schumpeter and other teachers. In short, he was growing up. The Marxist students, filled with their own importance, were “an unattractive, intellectually shabby lot.” A final blow to his illusions about the New Deal was dealt when he spent a summer in Washington working in the Resettlement Administration, “the very epitome of a New Deal agency.” Before very long that agency was taken over by the Department of Agriculture and its ambitious projects gradually liquidated. Summing up his experience, he says, “It was a pattern that many similar programs, announced with great fanfare, have followed since: the War on Poverty, Model Cities, Appalachia—who can remember them all?”

As World War II neared its conclusion, Henry Regnery wondered if the world had lost its senses. Although Nazi Germany and the other Axis powers had no chance of winning, Hitler insisted on resisting down to the last drop of blood. President Roosevelt and the Allies had committed themselves to a policy of “unconditional surrender” along with unlimited bombing of major cities in Germany and Japan. Of particular concern to Regnery was the Morgenthau Plan (the inspiration of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Roosevelt’s Treasury secretary), which would have made Germany a permanently vassalized country.

It was at this moment in late 1944 that, providentially, Henry Regnery met Frank Hanighen, a Harvard graduate and political journalist, who had just started a Washington newsletter, Human Events. Hanighen was familiar with the ins and outs of Washington’s power structure—visiting the Mayflower Hotel bar nightly to learn the latest from members of Congress and White House aides—and “harbored no illusions whatever about those who manipulated [power].” Associated with him was Felix Morley, then president of Haverford College and previously editor of the Washington Post, who had opposed America’s entry into the war. Regnery decided to join Hanighen and Morley in their enterprise, providing resources and a Midwestern business sense. During their six years together, this triumvirate made Human Events an influential publication despite its limited financial resources and a circulation that never exceeded five thousand subscribers.

Not having the means to publish a magazine—a long-term goal—“we resorted to the pamphlet,” that venerable Western institution that included John Milton’s Areopagitica, Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, and the Federalist Papers. The first Human Events pamphlet contained two speeches by Robert Hutchins, president of the University of Chicago, who argued that “we could not attain peace with vengeance” and that however Americans felt about their wartime enemies, “the time had come for reconciliation.” The pamphlets covered a wide variety of subjects, such as Russian slave-labor camps, the failure of high schools, the income tax, Gandhi and Indian independence, and minorities.

Human Events and the pamphlet series gave Regnery invaluable experience in publishing—he had taken over the printing and distribution of the newsletter and the pamphlets—and the chance to meet people he would not have otherwise met. He learned something about “how ideas are communicated and how they are suppressed and what constitutes public opinion and how it is manipulated.” The success of the pamphlets and the three books that Human Events published (especially Hitler in Our Selves by the Swiss philosopher Max Picard) whetted Regnery’s desire to get into publishing full time. He and his Human Events colleagues Hanighen and Morley parted amicably, and in March 1948 the Henry Regnery Company was incorporated.

Regnery attracted contrarian authors and revisionist books like bees to honey.

The first Regnery catalog set forth its mission: “To contribute to the re-establishment of the interchange of ideas and opinions that has been characteristic of the Western tradition and that is indispensable if civilization is to recover from the shattering experience of the war.” Thus, from the beginning, the Regnery Company took an editorial position markedly different from that of the major New York publishers, which were willing dispensers of modern liberalism.

Regnery attracted contrarian authors and revisionist books like bees to honey. As Jeffrey Nelson points out in his introduction to Regnery’s memoir, Perfect Sowing: Reflections of a Bookman, Regnery became the chief publisher of World War II historical revisionism. Fiercely debated was whether President Roosevelt had engineered America’s entry into the war. The intellectual establishment accepted the orthodox side of the controversy that World War II was an unconditional victory, while revisionists argued that it was a political and moral failure.

In William Henry Chamberlin’s America’s Second Crusade, the author concludes that the net result of the war had been “to strengthen an equally vicious and more dangerous form of totalitarianism [Soviet Russia] as a substitute for those we destroyed.” There followed Charles C. Tansill’s seven-hundred-page Back Door to War, which begins, “The main objective in American foreign policy since 1900 has been the preservation of the British Empire.” Always willing to present the other side, Regnery gave Admiral Husband Kimmel, invariably blamed for the Pearl Harbor disaster, a chance to give his version of events in Admiral Kimmel’s Story. “His book,” says Regnery, “is a testament to a brave man, who, despite the most shameless calumny, never lost his dignity or confidence in his own integrity.”

Regnery regarded the inability to acknowledge evil as the root of liberal errors: “For the liberal,” he wrote, “evil is not an existential fact, but a social problem, which is doubtless one of the reasons liberals found it so difficult, if not impossible, to recognize Stalin and Soviet Russia for what they were.” Regnery had no difficulty in recognizing the elemental totalitarian character of communism.

Anticommunism was the glue that brought together and held together the disparate strains of American conservatism for more than four decades, from the 1940s through the 1980s. Henry Regnery was an early major supplier of that glue. Among the Regnery books on communist subversion were Louis Budenz’s The Cry Is Peace, Stefan Possony’s A Century of Conflict, and James Atkinson’s The Politics of Struggle. The path of an ex-communist, Regnery points out, “is not an easy one.” He must confront not only the violent hostility of his former comrades, but “the [unending] animosity of the liberal intellectual establishment.” “The liberal will forgive a Communist,” he says, “but never the Communist who leaves the party and openly fights it.”

Henry Regnery was proud to have published Bill Buckley’s God and Man at Yale. “I felt I had played a small part in launching the career of a man,” he said decades later, “who has since attained a position of great influence.” Buckley frequently stayed at the Regnery home. “He was a great favorite with our four [small] children,” Regnery recalled. “He brought them presents, played games, and told them stories. Most memorable of all for them was his performance on our piano of ‘Variations on the Theme Three Blind Mice.’” Buckley would begin quietly but become more and more flamboyant, ending in a “perfect torrent of pyrotechnics.” At which the Regnery children, brought up on Bach and Mozart, would say in one voice, “Do it again!”

Regnery retired in 1977 but reentered the business world a few years later with a new publishing venture, Regnery Gateway. He continued to serve on a number of conservative and artistic boards, including the Intercollegiate Studies Institute as chairman, the Philadelphia Society as president, the Chicago Conservatory of Music, and the Cliff Dwellers, a Chicago club devoted to the arts. He died in 1996 at the age of eighty-four.

Although Regnery denied that he set out to be the go-to publisher for the conservative movement, a survey of the Regnery list reveals dozens of conservative, libertarian, anticommunist, and religious titles by such conservatives as Bill Buckley, Russell Kirk, Freda Utley, Frank Meyer, James Burnham, John Dos Passos, T. S. Eliot, and Romano Guardini. Unquestionably, Henry Regnery published the books that enabled conservatives to break through the liberal barrier in publishing once and for all.