Glenn Loury is the Merton P. Stoltz Professor of the Social Sciences in the Department of Economics at Brown University, a position befitting someone who has had an enormous impact on both the field of economics and American discussions of race. Over a long career, stretching from the 1970s until today, Loury has attempted, among other things, to diagnose the problems leading to unequal status and outcomes for black people in the United States. He sees those problems as often self-induced.

Loury was the first black person to be tenured in Harvard’s economics department, and race is a reference point in much of his economic work. His most famous academic article, “A Dynamic Theory of Racial Income Differences,” argues that economic success is related to “the impact of an individual’s family and community background on his or her acquisition of labor market skills.” Affirmative action only puts less qualified individuals into positions where they are doomed to fail. Instead, Loury argues, we must help people in families and communities with less-than-adequate social capital to gain that capital in other ways.

From 1980 until the late 1990s Loury was a Reaganite. He was a darling of the right, once sitting next to President Reagan at a national summit on race. Because of this, he was treated with skepticism by other black academics.

That changed starting around 1999, as Loury began to give talks decrying colorblindness and was welcomed into the academic left by figures such as Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Cornel West. He started to express sympathy with the notion that incarceration rates showed a systemic bias against African American men in the United States justice system. In 2008 he published a book based on this work: Race, Incarceration, and American Values, two years before Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, which became more widely known.

Then, almost as quickly as he shifted to the left, he moved back to the right. He voiced damning criticisms of the Obama presidency and was dismayed at the lionization of Trayvon Martin and the Black Lives Matter movement. Since that time, Loury’s political views have been harder to pin down, but his outspokenness has only increased. (Over three hundred episodes of his podcast, The Glenn Show, have now been recorded.)

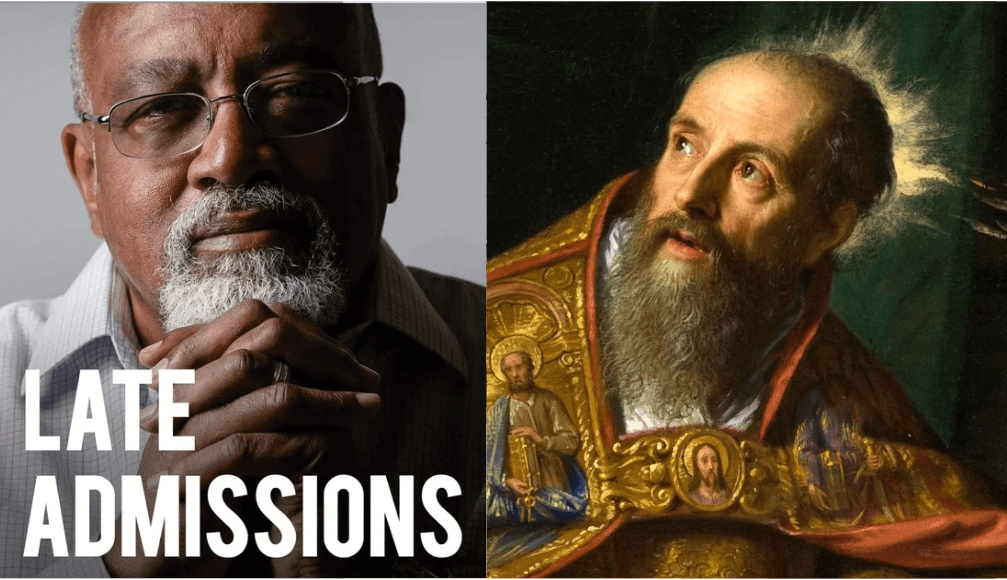

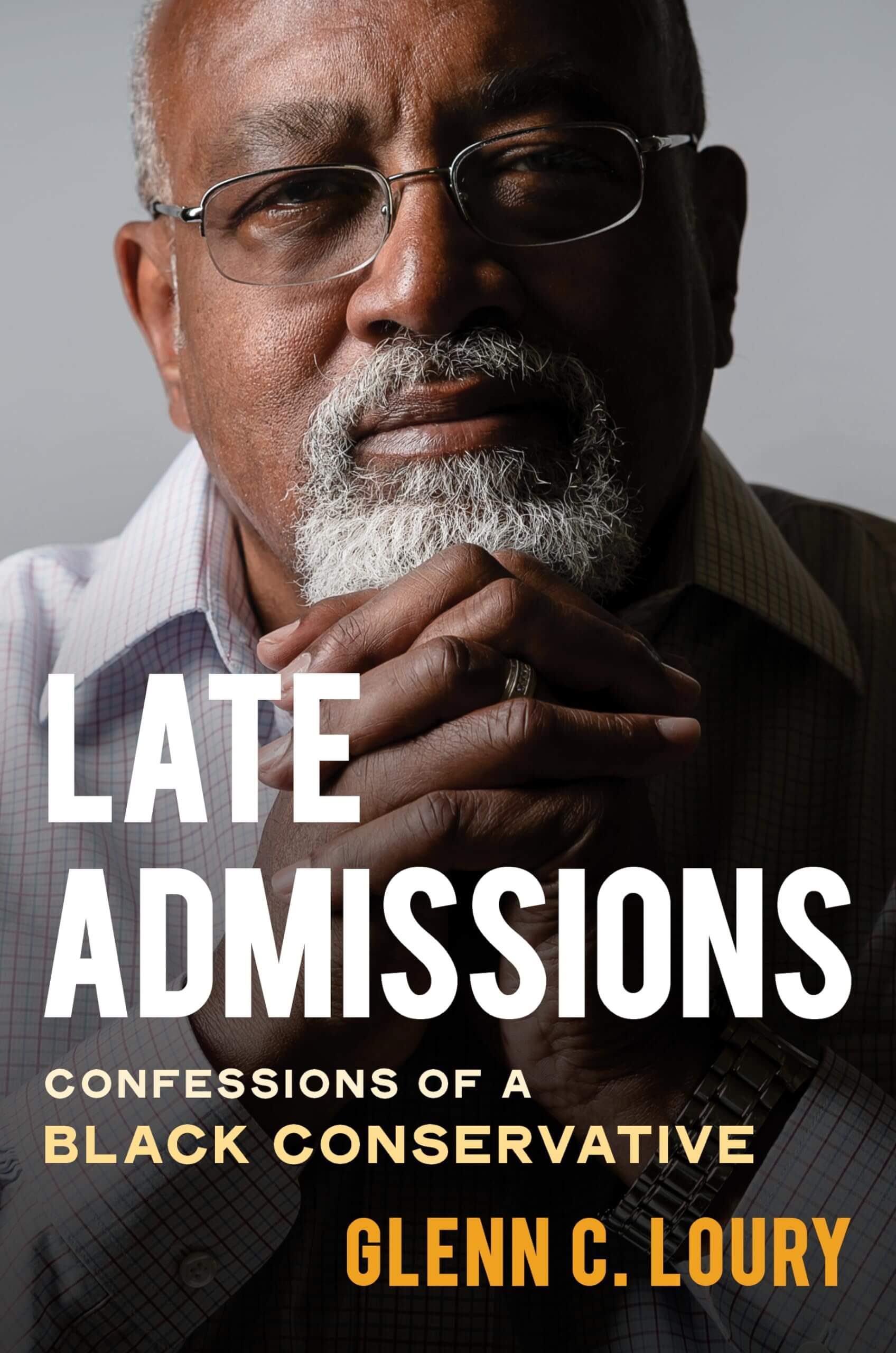

Late Admissions divides its pages between the professionally academic and the personally probing. As a scholar’s memoir, the book is a fascinating read. But the contextualization of Loury’s academic odyssey within a colorful and often sordid personal life is what makes the book truly noteworthy. Loury begins his story on the South Side of Chicago, where he was raised by an alcoholic mother, an absentee father, his grandmothers, and a host of uncles and aunts. His ascent from the inner city to Northwestern, MIT, and Harvard is inspiring. But throughout his narrative, Loury is haunted by personal demons—chief among them lust for women and drugs.

Loury’s vertiginous spirals between what he calls “the cover story” (well-adjusted, successful academic with a stable family) and “the real story” (drug-addicted womanizer who rarely sleeps) is gripping. This is a moving memoir of political conviction and personal foible, and it is also more than that. It is a meditation on selfhood. It is a bildungsroman. Its literary predecessors are not biographies or even autobiographies but works of literary and philosophical introspection by such authors as Pascal and Emerson.

Loury mentions many foundational texts in the course of his book. As an undergraduate at Northwestern University, he writes, “I found myself especially taken with the stories and novels of Franz Kafka and Thomas Mann. The existential philosophy of Sartre and Camus fascinated me.” His favorite philosopher is Nietzsche. But toward the end of this memoir, he mentions the two authors I see as most important to his project: Ralph Ellison and Saint Augustine of Hippo.

Ellison’s Invisible Man traces a black liberal’s journey to black conservatism. The way the narrator of Ellison’s novel comes to see through the insincerity of Marxist activism on behalf of African Americans in Harlem matches Loury’s own journey to a pro-capitalist, anti–affirmative action position. Both Ellison’s narrator and Loury come from poverty. Both struggle to understand and live up to the advice and ways of their family. Ellison’s protagonist is caught between what he calls the “ass struggle and the class struggle” (i.e., romance and Marxist activism), just as Loury is caught between the many lovers (and children) from his “real story” and the marriage and professional success of the “cover story.” The existential questions of Ellison’s invisible man are also Loury’s: “What kind of man was I becoming?” and “Must I strive toward colorlessness?”

But there is a twist in Loury’s narrative that is not present in Ellison’s. Loury becomes in his later career decidedly more liberal again. His first public move back toward what his liberal friends and colleagues considered “blackness” (i.e., a belief in black exceptionalism, affirmative action, and commitment to the inner cities) was a review he wrote of America in Black and White, by his friends Stephan and Abigail Thernstrom, a work in which they argue that inner-city black communities might be a lost cause. Loury replies with an “insistence that conservatives needed to become more proactive on the race front.”

Loury writes that despite “breaks with the conservative mainstream, I still considered myself to be a conservative, albeit increasingly a critic—not an enemy—within.” An exemplar of independent thought, Loury has cultivated a perspective that combines a fierce longing for social justice with a firm grounding in economic and social reality. He can be caustic. In podcasts of late, he has been an ornery, unclassifiable thinker willing to engage with anyone who has a good idea about anything, from Cornel West to Heather Mac Donald. Loury’s memoir is an account of how he came to have such a vital nonconformist role among today’s public intellectuals.

Like Augustine’s Confessions, Late Admissions is also a Christian autobiography, a story of sin and redemption. Loury lives most of his life seemingly oblivious to Christianity. Only when he reaches rock bottom as a drug user—as alcohol leads to marijuana, then to powder cocaine, then to crack—is he led to faith. He attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings while staying at a long-term addiction recovery center in Boston, and one day a visitor from Charles Street AME Church recites Psalm 23 with him. “The words of the psalm,” Loury writes, “through their beauty and wisdom, drove home to me that my isolation was not such a good thing after all, and that I was not as alone as I thought. I read them, for the first time, not as a set of metaphorical propositions about God, but as a personal message meant for Glenn Cartman Loury.”

So he is saved that Easter. But his story is more tangled, less final than Augustine’s: “Some higher power, I felt, had left its mark on me. Even so, I subsequently relapsed.” (Loury is a serial relapser, both with drugs and with women.)

“To Carthage then I came, where I found myself in the midst of a boiling cauldron of lust,” writes Augustine at the beginning of Book 3 of the Confessions. Augustine’s embarrassment at having a son, Adeodatus, by his Carthaginian mistress is reminiscent of Loury’s absenteeism in the raising of Alden, his own son by a mistress. Augustine and Loury even share the experience of being witnesses to the alcoholism of their mothers. Augustine offers glimpses of his mother’s compulsion and her stern ways of overcoming it. Loury sees the staggering steps of his mother when he is still a young man and receives drunken phone calls from her when he is older.

In addition to their parallel stories, the shared literary method and Christian context of the texts puts them in conversation. Their approach is one of inwardness verging on compulsive introspection (which others might call egotism), even about introspection itself. Loury’s musings on his indulgence in self-accounting are some of the most fascinating parts of the book.

Yet introspection about introspection is always a little suspect. Writers intelligent enough to theorize their confessionals are also intelligent enough to swerve away from true confession when it perhaps most matters. Though Loury gives us depths, one suspects there are places he cannot reach, vices he will not reveal. The trail is too thick with lies, deception, and pain. Nonetheless, Loury’s struggle with veracity and responsibility is the struggle of all Christians, and his story, like Augustine’s, is instructive for that very reason.