It is a truth universally acknowledged by anyone who has taught music history on an Anglophone campus: streaming platforms have intensified the characteristic presentism of the undergraduate worldview to an extent that was impossible during the days when CD booklet annotations and LP liner notes imparted painless historiographical lessons. In consequence, expecting music students in America, Australia, or even Britain to be aware of previous ages’ outstanding pianists is asking for the moon, even when these undergraduates themselves are studying piano.

Go through the roll call of past pianistic names and see how often you elicit any response except incomprehension. Claudio Arrau? Alfred Cortot? Edwin Fischer? Walter Gieseking? Rudolf Serkin? You might as well be declaiming the sequence of Avignon popes. Nor would a recitation of the past’s world-famous violinists, cellists, or opera singers produce a different result.

Yet one pianist continues to prompt recognition: Glenn Gould. Somehow his existence, and among pianists his alone, excites the student imagination. The enthusiasm often springs from considerable knowledge of Gould’s Bach recordings (rarely from his other recordings), combined with substantial reading of Gould’s prose and familiarity with his career. His career is a curiosity—his prose mostly poison.

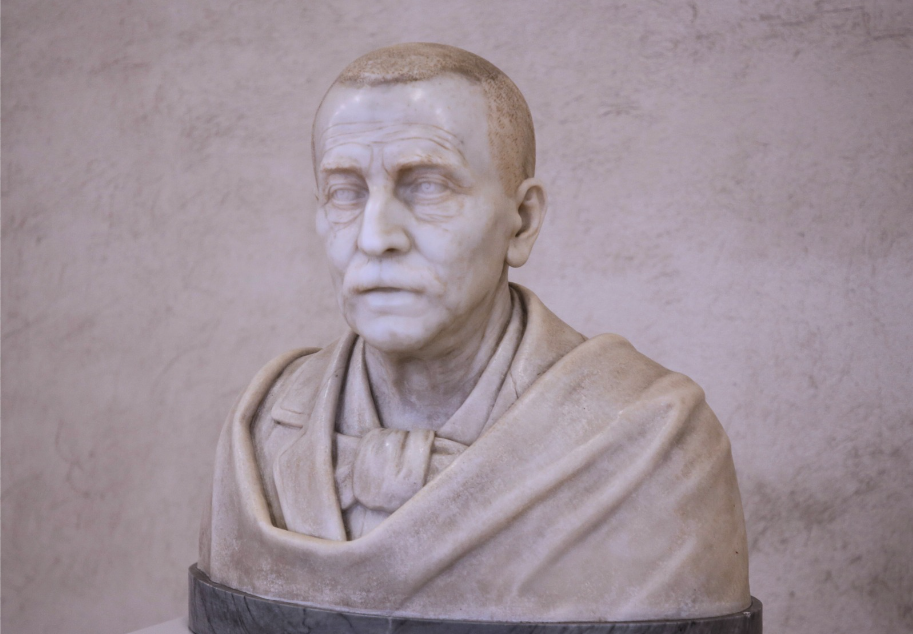

Born and almost entirely resident in Ontario, Gould (1932–1982) had hardly any conventional instruction in music and imperiously disdained what he did have. While he composed occasionally, he cared above all for the piano, in his playing of which he soon outgrew anything which his Canadian surroundings could offer. He came to the notice of that most intimidating and skeptical among conductors, the Cleveland Orchestra’s George Szell. Spurning euphemism, Szell declared, “That nut is a genius.”

All the glittering prizes of classical superstardom appeared to be Gould’s. He collaborated as concerto soloist with no less a podium star than Leonard Bernstein. He managed the remarkable feat of imposing his own weird interpretations on the seldom overawed “Lenny,” who generously conceded Gould’s right to his aesthetic opinions, even as he distanced himself from them. There seemed nothing in concert life that Gould could not achieve. Aged twenty-four, he already had to his credit a recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, which would soon make its way onto critics’ lists of all-time classics.

Then Gould threw it all away. More precisely, he mistook his visceral aversions for deeply cogitated spiritual convictions. From the unexceptionable premise that he found concert and operatic life hateful, he leapt to the conclusion that concert and operatic life was hateful in its very essence.

He suffered from stage fright, which has afflicted numerous other classical musicians. (Andres Segovia would vomit in terror before many of his guitar recitals, although in front of an audience he conveyed imperturbable stoicism, a transformation whose effects the present writer witnessed in 1972 when Segovia played at Oxford’s Sheldonian Theater.)

Lots of fine musicians abandon public performance when their nerves are torn to pieces. Often it is commendable that they do, since as Chesterton sagely remarked, “The men who really believe in themselves are all in lunatic asylums.”

But scarcely had Gould the live performer been consigned, with much mourning, to the grave—he quit the concert stage forever in 1964—when there took place the abrupt parturition of Gould the Guru, with results as astounding as Minerva’s eruption from Jupiter’s head. Robert Lowell, in one of his darkest verses, called Minerva “the miscarriage of the brain.” It is an epigram that the antics of Gould the Guru, in contradistinction to Gould the brilliant technical maestro and intermittent artist, too regularly confirmed.

Gould opted out of life. So phobic towards germs that even the occasional handshake tormented him (Gouldologists dispute among themselves whether he ever had sexual relations), and so addicted to pill-popping for imaginary ailments that real ones slew him at the age of fifty, Gould dwelled almost entirely within his Toronto home and his recording studios, striving to abolish all distinctions between the two.

Friendship he interpreted as license to inflict telephonic soliloquies upon well-wishers night after night for hours. Some of the well-wishers were recording labels’ accountants, whom he would browbeat with demands (of breathtaking impudence in that pre-internet epoch) that he be accorded forthwith the latest details regarding not just his American and British royalties but his Australian and New Zealand ones too.

Now and then Gould would write essays on music, essays occasionally pertinent and downright brave: he deserves credit for praising Paul Hindemith and Richard Strauss at a period when most musicologists undervalued both. But his disquisitions on performers, as distinct from composers, had as much substance as the voluble expression of a teenage crush. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Barbra Streisand, Petula Clark: all these ladies he extolled with indiscriminate elation, as he did the Moog synthesizer. The language of his homages might have suggested the idioms of undemanding child psychologists, but the thought processes and the surging hormones involved were pure Holden Caulfield, when they did not evoke that other and more alarming (because self-referential) J. D. Salinger protagonist, Buddy Glass.

Well, what of that? As H. L. Mencken once told Henry Wallace to his face during the latter’s communism-compromised 1948 presidential bid, “We’ve all written love letters in our youth that would bring a blush later on. There’s no shame in it.” Perhaps exposure to Gould’s dithyrambs on Petula Clark gave one reader in Ottawa or Omaha comforting insights into “Downtown” or “Don’t Sleep in the Subway,” and if so, honi soit qui mal y pense. Rather, Gould the Guru’s moral failure started when, emboldened by American magazine editors’ willingness to disseminate his fanboy ebullitions, he laid down laws for the rest of the human race.

Oliver Cromwell famously and commendably told his crazier rivals, “I beseech you in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you might be mistaken.” Gould was never mistaken, and no one exceeded Gould’s persistence in notifying the planet of his inerrancy.

The criterion that Matthew Arnold judged essential for any critic worth serious perusal—namely, a determination, however imperfectly realized, to get out of the way and let the work being discussed speak for itself—either moved Gould to unblushing scorn or (a more probable explanation) never came to his notice. The Glenn Gould Reader contains few if any paragraphs that cannot be summed up by a variant of Alexander Pope’s couplet praising Newton: “Music and music’s laws lay hid in night: / God said: ‘Let Glenn Gould be!’ and all was light.”

Yet any bewildered reader whose experience includes authors other than Gould soon appreciates how ahistorical Gould’s mind fundamentally was, for all its occasional obeisances to half-forgotten early-seventeenth-century masters such as Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck and Orlando Gibbons. Indeed, the more one reads of Gould, the clearer it becomes that his ignorance resembles what Dorothy Parker called an Empire State Building among ignorances: engendering awe by its sheer size.

Freedom from the punitive schedules of the mere touring artist gave Gould time for reflection—a great deal too much time, as it proved.

To read Gould on, say, Schwarzkopf is to have one’s comprehension of the singer illuminated perhaps 10 percent of the time; but the other 90 percent of Gould’s commentary on her output teaches all too little. Admittedly, within the general public’s ranks, Schwarzkopf—even at the peak of her celebrity—was renowned more as an honored name than for her specific interpretations; few among Gould’s readers, therefore, will have been in a position to attempt point-by-point querying of his utterances on her significance.

With Mozart and Beethoven, conversely, Gould found himself in the invidious position of dealing with figures whose creations (unlike, for example, the Hugo Wolf Lieder that Schwarzkopf championed) Joe Public could speak about with some direct experience. One escape around the attendant frustration occurred to Gould: if the masses revered Mozart and Beethoven, this constituted all the more reason for him not to do so. Accordingly he chose to belittle both masters, and thus to keep intact his reputation for shock value.

Given the sheer embarrassing ineptitude of most Gould recordings devoted to composers whom he despised, let us be grateful that his discography was not still bigger and more indiscretion-infested than it is. Really, in none but Bach could Gould effect that ecstatic interpretative communion of which he repeatedly and pretentiously spoke. Even in Bach, moreover, his mania for vociferously humming along with the music which he played indicates a sustained resentment for the common listener’s understandable assumption that the composer’s thoughts might matter more than Gould’s. (Video footage of him in his performing days, writhing for the cameras, reveals equal narcissism, and makes an annoying contrast with, say, Vladimir Horowitz’s and Arthur Rubinstein’s avoidance of superfluous head and shoulder gestures, though Gould showed better selfcontrol in this regard at the outset of his fame.)

Freedom from the punitive schedules of the mere touring artist gave Gould time for reflection—a great deal too much time, as it proved. The older Gould got, the more he philosophized, badly.

Gould possessed an even more limited understanding of the religious impulse than his likewise short-lived contemporary (not to mention fellow pharmaceutical garbage dump) Kenneth Tynan did. At least Tynan—who was a guru of art criticism in something like the way Gould was for music—had known C. S. Lewis, and with one element of his being (as the nightmarishly vivid biography by his widow, Kathleen Tynan, confirms) he longed to be devout. Gould had no keener interest in organized religion than in metallurgy. His outlook is best summed up in the cruel joke that the wife of the British television luminary Sir David Frost once told about her husband. A questioner had asked if Sir David was an atheist. “Certainly not,” she snapped. “He thinks he’s God.”

Insofar as Gould subscribed to a nonpersonal faith, that faith was technocracy. Untainted by any Marxist allegiance, he nevertheless shared the young Marx’s preposterous dream about how we are all going to be geniuses—all great painters and great sculptors and great writers and great composers—if only we can get The Man off our backs. For Gould, however, The Man was not the evil capitalist of Marx’s fantasies but the evil concertgoer.

Here is Marx in 1845:

In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Next, an extract from the Thoughts of Chairman Gould. Here he burbles about how in the earthly paradise there will be no musicians and no public because the musicians and the public will be . . . all of us:

[The] listener is no longer passively analytical; he is an associate whose tastes, preferences, and inclinations even now alter peripherally the experiences to which he gives his attention, and upon whose fuller participation the future of the art of music waits. He is also, of course, a threat, a potential usurper of power, an uninvited guest at the banquet of the arts, one whose presence threatens the familiar hierarchical setting of the musical establishment.

It gets worse. A prominent strand of utopian whimsy—one as prominent among self-proclaimed Catholics such as England’s Eric Gill and among sincere Jeffersonians such as the United States’ Charles Ives as among self-confessed Marxists—is the idea that art should not exist. Not, be it emphasized, because of Plato’s worries about the dangers posed by works of art to public mores, but because our actual lives are somehow the true works of art.

No other meaning can be elicited from the following Panglossian passage by Gould: “In the best of all possible worlds, art would be unnecessary. Its offer of restorative, placative therapy would go begging a patient. The professional specialization involved in its making would be presumption. The generalities of its applicability would be an affront. The audience would be the artist and their life would be art.”

The worst vice here is Gould’s psychobabbling reductionism: “placative therapy.” King Lear is “placative therapy,” is it? John Donne’s and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s sonnets are “placative therapy”? The Brothers Karamazov? Flannery O’Connor’s fiction? Madame Mao herself was less degraded in her view of art’s function than the Gould of those sentences.

The British philosopher Bryan Magee, an expert on Wagner and much else, gave a poignant account of a dying man who, ravaged by an inoperable and painful cancer, voiced one final wish. He asked to be dragged along to an opera house in order that he might hear the ravishing beauty of Der Meistersinger’s Act III once more, live, before he died. Was that a mere craving for “placative therapy”? When he faced the Grim Reaper, a recording no longer sufficed. Instead, he longed to hear the music rendered not by a faultless stereo system but in a flawed human staging by flawed human beings, each of whom was made in, and bears for all time, the imago Dei.

In his memoir Darkness Visible, William Styron explained with searing candor his determination to commit suicide. From this fate, to which his hellish melancholia kept prompting him, he was rescued by another piece of music: the overheard strains of Brahms’s Alto Rhapsody. He had not previously cared for Brahms and had read little, if anything, about the man. Nevertheless, in that dark night of Styron’s soul, some indescribable vision of a happier land, perceived through those overheard strains, made Styron desist from killing himself. Of the possibility that such a life-and-death deliverance could occur, Gould, as far as can be ascertained, suspected nothing.

In a critique produced shortly before Gould’s death, the musicologist Harvey Sachs (who himself had long lived in Canada, though born in Ohio) quotes the pianist’s own words to incriminate him, including these:

Let us say, for example, that you enjoy Bruno Walter’s performance of the exposition and recapitulation from the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony but incline towards [Otto] Klemperer’s handling of the development section, which employs a notably divergent tempo. . . . With the pitch-speed correlation held in abeyance, you could snip out these measures from the Klemperer edition and splice them into the Walter performance without having the splice produce either an alteration of tempo or a fluctuation of pitch.

To which Sachs responds:

For Gould, this represents one possible means of returning to what he sees as a pre-Baroque-period attitude towards music: the composer, performer and listener are united in the same individual. This is absurd, in the first place because although there was generally little distinction between composer and performer in those days, most listeners were incapable of either composing or performing, just as is the case today; and it is absurd in the second place because the senseless activity of patching together two or more versions of a work can in no way be compared to the achievement of composing or playing even the most elementary piece. If I, as a person who loves the art of painting but cannot manipulate a brush myself, were to remove the head of Christ from one print of Piero Della Francesca’s Resurrection and stick it on the body of a different print of the same painting, I would not expect to be credited with creative powers for having done so—even if I had made sure that the proportions were correct.

Gould’s philosophic pretensions do not impress: “He is a philosopher in the way in which most of us are philosophers: he supplies a philosophy in order to justify his own deeds and predilections. That he achieves this more effectively than most of us are capable of doing may make his rationalizations fun to read, but it does not transform them into anything other than rationalizations.”

Confronted with Gould’s “placative therapy,” Sachs is pitiless, saying that art

stimulates and disturbs far more than it tranquilizes, it heightens and sharpens awareness more than it pacifies. Presumably “the best of all possible worlds,” according to Gould, would be one in which every human being would be intellectually capable of living life to the fullest and spiritually capable of coming to terms with himself and everyone around him. But even if such a thing could happen, would every person live life and accept others’ lives in the same way? Would all people, in short, be the same person? If not, the need for communication among human beings would be increased rather than decreased; and art is above all a concentrated form of communication. Only a world without death—the one inescapable human truth—could afford to be a world without art. . . .

While Gould is a very clever man, and one who is skilled in a number of areas, playing the piano is what he really does best. No one wants him to confine his activities; but what many of us would like him to do is to step out of his antiseptic little corner, move among sweating humanity, and remember that Bach and Beethoven and Schoenberg, like the rest of us but unlike the Moog synthesizer, also lived, loved, perspired, and died. . . . The true magister ludi does not merely twirl the dials from a glass booth: he stakes his life on every move in the proceedings.

None of the foregoing implies that Gould needed theism to be intelligent, though it does accentuate the intellectual gulf between Gould and a writer like George Bernard Shaw, who—for all his theological heterodoxy and his bouts of eugenicist villainy—admitted that “art has never been great when it was not providing an iconography for a live religion.” What it does suggest is the peril awaiting those young music students who know Gould’s music commentary and almost no one else’s.

Gould’s credo constitutes a clear and present danger. To the extent that it continues to leave its mark on those in the classical music industry who determine for the masses what shall and shall not be legitimated, it needs to be opposed. Sachs excepted, who, we are entitled to ask, is daring to oppose it?