History has not been kind to Gerald R. Ford, the thirty-eighth president, whose twenty-nine-month tenure began with the resignation of the disgraced Richard Nixon and ended with his own presidential defeat in 1976. In the twenty-five years following Ford’s presidency, five prominent academic surveys designed to rate and rank the presidents placed Ford, on average, at twenty-sixth—down in the middling ranks with Chester Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, and Jimmy Carter. The Ford biographer John Robert Greene characterized him as “the man who saved the country from Nixon, prepared the country for Carter and Reagan, and did little of substance on his own.” In other words, his was a caretaker presidency of little historical significance.

This assessment flowed in part from the view of him shared by many leading journalists and politicians of his time—a plodder, small gauge, lacking vision, reflexively partisan, prone to word mispronunciation and occasional malapropisms. Lyndon Johnson famously wondered if he hadn’t played football too often without a helmet during his University of Michigan days and declared that Ford couldn’t “walk and chew gum at the same time” (an insult actually expressed with greater crudity).

Then there were the Saturday Night Live parodies, with Chevy Chase portraying Ford as a hopeless stumblebum who couldn’t walk down the steps of Air Force One without entangling his feet. New York magazine illustrated a scathing profile by Richard Reeves with a cover portrait of Bozo the Clown sitting at the presidential desk and used the headline “LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES.” Reeves closed his piece by declaring, “We have always cherished the promise that any one of us could be president. Any one of us now is.”

Throughout the decades following Ford’s heyday, though, some dissident voices have suggested that Ford didn’t deserve the persistently negative portrayals and certainly not the ridicule. They have argued that Ford not only was a man of rectitude and character, which hardly anyone ever questioned, but also was more politically sagacious and effective than his reputation would suggest. They are joined in this view by Richard Norton Smith, the noted biographer of such important American figures as George Washington, Nelson Rockefeller, and Thomas E. Dewey. A decade ago Smith set out to produce a comprehensive Ford biography, combining, as he put it, “scholarly rigor with popular accessibility.”

The work is now out, and it can be said that Smith has fulfilled his intention. In 710 pages of text, he displays all the scholarly rigor for which he is well known and gives his readers a fast-moving train ride of a narrative, with plenty of lush background scenery and up-close views of human activity. More than simply a biography, An Ordinary Man presents a window on American history during the first three decades of the country’s post-1945 global ascendancy.

Smith concedes an element of truth in the argument that Ford’s presidency was largely “reactive.” And certainly the biographer’s title signals a recognition that Jerry Ford wasn’t an extraordinary figure in the vein of a Washington or the Roosevelts. As Ford charmingly described himself, employing an automotive metaphor, “I am a Ford, not a Lincoln.”

In that vein, Smith assesses the Ford presidency in terms of the awesome challenge faced by an ordinary man thrust into the presidency by extraordinary events, without seeking the office, without any electoral mandate to bolster his leadership, and facing a populace highly inflamed by abuses of office that had nothing to do with him. That’s a good story if told with dispassionate precision, as Smith’s story is. It’s also the story of a good man who in many respects exemplified the cultural mores and folkways of the influential and energetic American Midwest.

The person later known as Gerald R. Ford was born on July 14, 1913, in Omaha, Nebraska, and christened Leslie Lynch King, Jr. His father, scion of a wealthy Midwest business family, was an erratic and occasionally violent man. His mother, Dorothy Gardner, was the spirited and bright daughter of an Illinois dry goods merchant and funeral home operator. Soon after her wedding in 1912, Dorothy realized she had married a dangerous bully who posed a physical threat to her and the couple’s infant son. She fled Omaha and settled in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where her parents then lived. Eventually she divorced King and married Gerald Ford, a sales agent and business manager “with a ramrod-straight posture and character traits to match,” as Smith describes him. Ford adored Dorothy’s child and embraced him as his own son, giving the boy his name and an abundance of paternal affection and guidance. His credo was, “The harder you work, the luckier you are.”

The child displayed an early tendency toward temper tantrums and had a severe stutter. But he outgrew both and developed into a winsome lad strongly influenced by his mother’s injunctive love and his stepfather’s example of probity. His consummate athletic skills, particularly as his high school’s football center, provided an outlet for his sometimes boisterous temperament and brought him a measure of local attention. Young Ford, writes Smith, “was accustomed to being noticed.”

After graduation in 1931 he enrolled at the University of Michigan, where he played football. Six feet tall and weighing two hundred pounds, with a buoyant sense of self-worth and a sociable nature, he became a notable figure on campus. In those Great Depression days, there was no family or scholarship money to finance his education. The young striver paid his way by waiting on tables, washing dishes, and selling his blood to the university hospital for $25 each time.

On the football field, he was named the varsity’s Most Valuable Player. In the classroom he accumulated a B average—“impressive,” in Smith’s view, when considered alongside his outside employment and athletic commitments.

After that it was on to Yale Law School, financed through a job as assistant football coach for the university. Graduating fifty-sixth in a class of 127, he returned to Grand Rapids to set up a law firm with a college friend. He served as the firm’s “outside man,” pursuing clients through his “people skills.” There weren’t many clients; his first-year income was about $1,200.

Then came World War II. Ford joined the Navy, obtained a commission, and volunteered for ship duty. As fitness director and gunnery officer on a converted aircraft carrier called the Monterey, he participated in major raids against Japan’s strategic land positions and survived numerous enemy aerial and sea attacks. He earned eight battle stars during the war.

In 1946 he returned to Grand Rapids as a figure of note, with an impressive physical stature, highly congenial to everyone he met, still remembered by many for his athletic exploits, and now possessing a Yale law degree and a stirring war record. He promptly was recruited to join his hometown’s leading law firm.

In August 1947 Ford met Betty Bloomer Warren, a young career woman then going through a divorce. Tall, beautiful, and elegant, she had pursued a dancing career in her youth and later became a fashion coordinator for an upscale Grand Rapids department store. They were married in October 1948.

By then Ford had left his law firm to run for Congress as a Republican against the sixty-three-year-old incumbent from the same party, Bartel Jonkman, who was closely associated with the corrupt Grand Rapids political boss Frank McKay. “I like your style, young man,” McKay told Ford, “but Bartel Jonkman is going to stomp all over you.” Betty wasn’t sure what to think of her fiancé’s political ambitions, but she went along with his efforts. “I thought, oh well, he’ll never beat Jonkman,” she later recalled.

But Ford stomped Jonkman, getting more than 60 percent of the primary vote and scoring a similar tally in the general election. Though he raised only $7,000 for his campaign, Ford out-hustled the incumbent with a grueling campaign schedule that few politicians could match. He placed the district at the center of his concerns while also embracing the foreign policy outlook advocated by his influential mentor, Michigan Senator Arthur Vandenberg, once an ardent anti-interventionist but now a Cold War hawk. He easily retained Michigan’s Fifth District through the next twelve elections.

Ford bolstered his political standing back home with a nearly perfect attendance record and a super-efficient constituent-service operation. Shunning knee-jerk partisanship, he occasionally went against his own party—voting, for example, to clip the wings of the imperious House Rules Committee, to foster the fanciful idea of a world federation, and to secure greater civil rights for American blacks. Such votes marked him as a mainstream moderate in keeping with Midwestern sensibilities. But on fiscal issues he consistently opposed runaway federal deficits and the ever-growing federal bureaucracy they financed. Like most Republicans, he shunned tax cuts that weren’t accompanied by offsetting spending reductions.

Smith writes that it didn’t take long for Ford’s “conciliatory talents of a rare order” to gain notice in Washington. He secured a coveted assignment to the chamber’s powerful Appropriations Committee, which maintained a watch over all federal expenditures. From that perch, and with his capacity for amassing knowledge in minute detail, Ford developed a rare expertise on the intricacies of federal spending. This was real power for a man who could combine, as Ford could, vast knowledge with a facility for inside legislative bargaining.

He thrived in the legislative setting. “I knew it was in his blood,” recalled Betty, “that he loved every minute of it.” He set his sights on becoming House Speaker, which required two developments: first, he had to emerge as his party’s premier leader and, second, the Republicans had to capture the House. He became minority leader in 1965, but the second imperative never materialized. By the early 1970s, frustrated with minority-party status and weary of incessant travel, he began making plans to retire after the 1976 election.

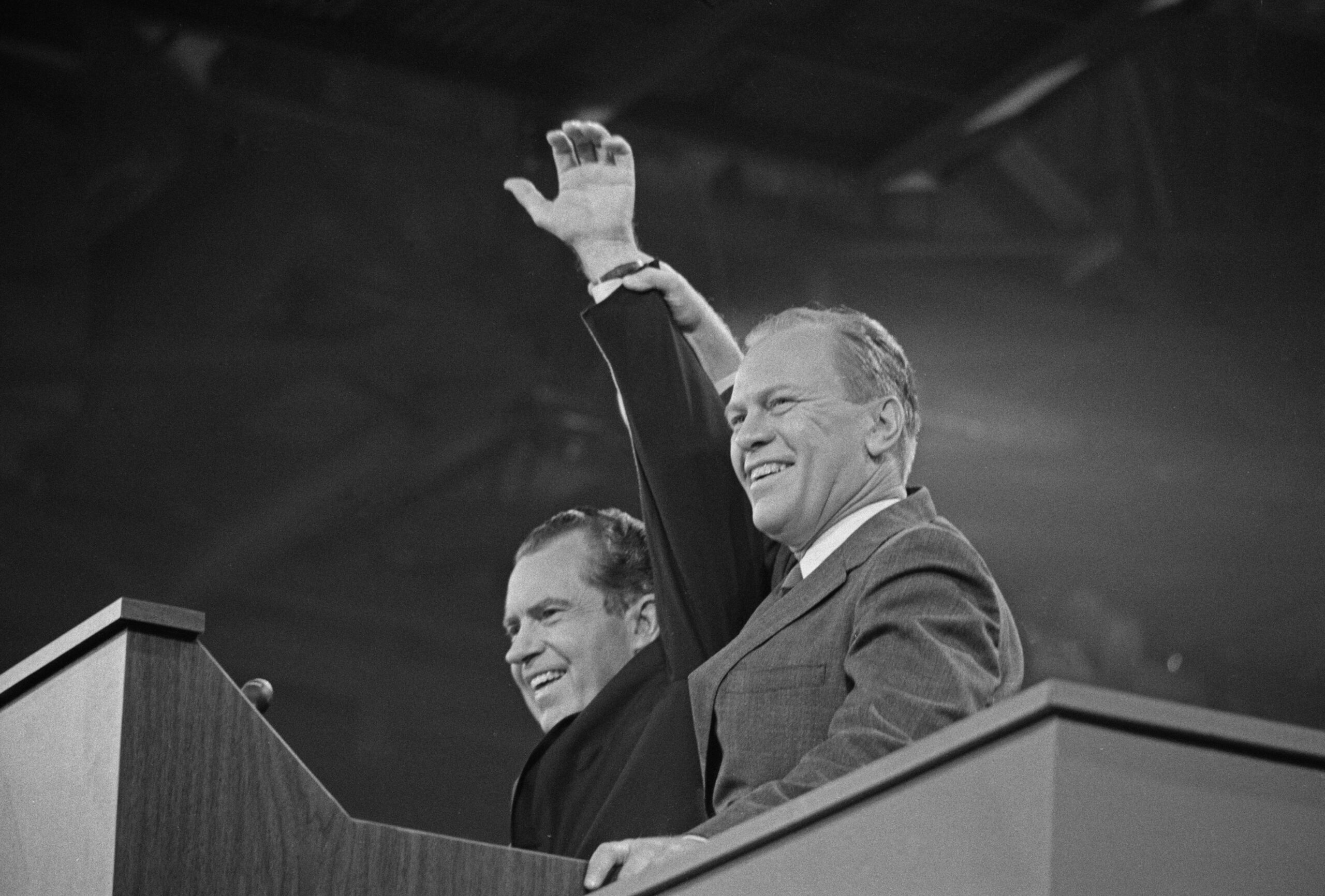

Then fate intervened. In 1973, with the stigma of Watergate nipping at President Nixon’s heels, a separate scandal of venality forced the resignation of Vice President Spiro Agnew. Nixon selected Ford as Agnew’s successor, in large measure because, of all the possible candidates, the Michigan congressman was most likely to be confirmed by Congress without difficulty. Within eight months of his swearing in, Nixon was out, and Ford was president.

The country was in tatters, beset not just by the debilitating Watergate scandal but also by an economy in stagnation (actually stagflation), a disruptive energy crisis, and a general sense of national bewilderment and gloom. Beyond that the 1974 midterm elections soon gave the Democratic Congress a veto-proof majority, and a North Vietnamese offensive against the South delivered to America the greatest military humiliation of its history. And his subsequent bid to win the presidency in his own right was undermined by a challenge from the party’s leading conservative, Ronald Reagan.

With all this bearing down on him, Ford made a decision that further undermined his political standing: he pardoned Nixon for any legal transgressions during his presidency. A firestorm of opprobrium ensued. Some thirty thousand telegrams flooded the White House, most of them opposed. Tennessee’s Republican Senator Howard Baker reported that his mail was running 90 percent negative. Editorialists thundered. Democrats pounced. The pardon, writes Smith, “marked the end of Ford’s consensus presidency.”

So how are we to assess the presidency of Gerald R. Ford? Smith takes pains to give him his due on various initiatives undertaken during his brief tenure, but few of those initiatives reached completion on his watch. The biographer cites the push for economic deregulation, which began with Ford’s focus on railroads and financial services, but most of the big action on this front took place under Carter and Reagan. Similarly, the modest arms control agreement negotiated by Ford and Leonid Brezhnev at Vladivostok in 1974 was merely a small step toward the treaty Reagan managed to negotiate with Mikhail Gorbachev a decade later. Smith also views Henry Kissinger’s Sinai II Agreement of 1975 as “paving the way for Jimmy Carter’s historic peace initiative in 1978”—in other words, another instance of incrementalism that reached fruition only later. History heralds Carter’s accomplishment, not Ford’s.

Smith, however, credits Ford’s efforts to negotiate the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which he hails as “a trumpet blast for human rights and a critical milestone on the road to Western victory in the Cold War.” That certainly is a defensible characterization, though it is also debatable. Reagan attacked Ford’s speech on the Helsinki outcome as “appeasement.”

But perhaps it’s best to acknowledge that Ford didn’t accomplish much simply because he couldn’t accomplish much with a hostile, naysayer Congress breathing down his neck, with no popular mandate to leverage in the national debates, with multiple inherited crises consuming his time and attention, and with that formidable Californian nipping at his heels for much of his tenure.

Indeed, the most remarkable aspect of the 1976 election might have been how close the incumbent actually came to victory despite the heavy baggage of Nixon and all the other elements of adversity stacked up against him. As Smith points out, a switch of just nine thousand votes in Ohio and Hawaii would have reversed the outcome.

Perhaps that Nixon pardon represented, as many believe, Ford’s margin of defeat. If so, it was still the right decision—and it was also courageous. It now is generally agreed that Ford was correct in perceiving that the question of Nixon’s fate, absent a pardon, would have roiled the nation for years, squeezing out any capacity for dealing effectively with the myriad problems at hand and moving the country toward a post-Watergate stability.

Ford gave the country a post-Watergate stability, and it was an impressive achievement. America doesn’t need a new visionary every four years. Often the times call for a more measured leader to calm the waters and steady the ship of state, to prevent crises rather than to go looking for them. McKinley, Coolidge, and Eisenhower come to mind, but none of those men, upon taking office, faced anything approaching the kind of adversity that Ford encountered. As the New York Times reporter James Naughton quoted one of Ford’s colleagues after his 1976 defeat: “The President is not a visionary. But he took office when we didn’t need to look into the future but assure ourselves we had one.” That was the assurance that Ford’s leadership gave the American people, and in giving it to them he rendered a profoundly valuable civic service.