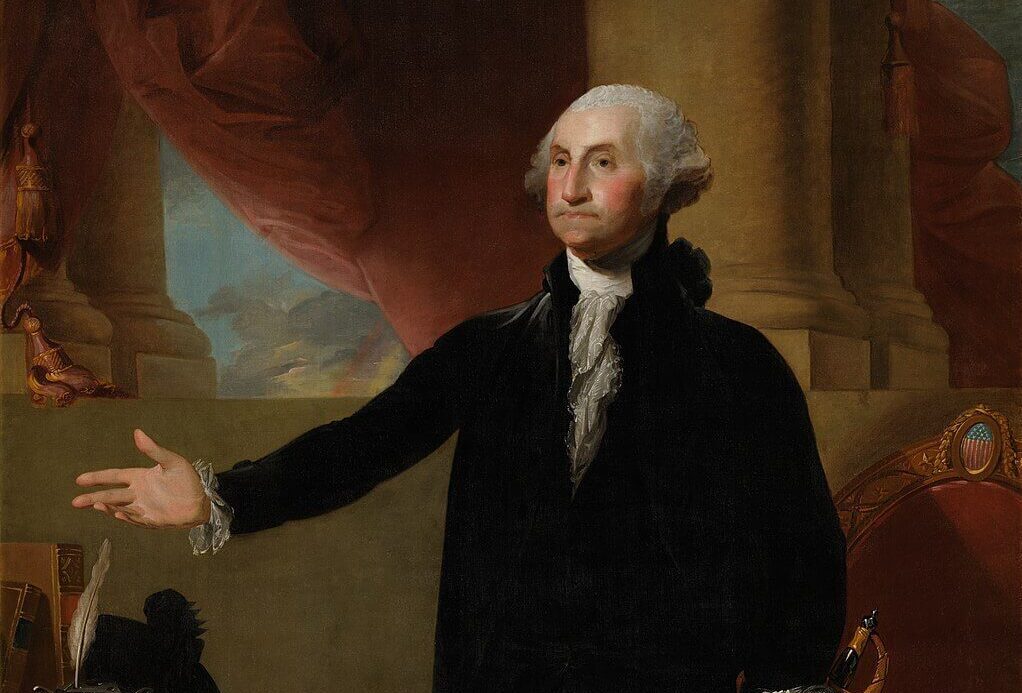

Commander in chief of the Continental Army and first president of the United States, George Washington was born February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County in the English colony of Virginia, son of Augustine Washington, an ambitious planter. Though Washington was deprived at age eleven, by his father’s death, of the chance of English schooling (which had been given his elder half-brothers), the young man’s early life was spent ascending the established ladders of success. He worked as a surveyor for rich in-laws, served as an officer in the colonial militia, and fought with distinction in the French and Indian War (his exploits were noted in London newspapers and by King George II). In his twenties, he married Martha Custis, a rich widow, won a seat in the colonial legislature, and inherited the main family estate of Mount Vernon, named for a British admiral. Only a commission in the regular British army had been denied him.

Britain’s efforts to tighten control over its North American colonies, however, pulled him steadily in the direction of disaffection. “Parliament,” he wrote a loyalist stepbrother in 1774, “hath no more right to put their hands into my pocket, without my consent, than I have to put my hands into yours for money.” That year, Virginia sent him as a delegate to the first Continental Congress; he attended the second Continental Congress in 1775 in his old uniform, showing his willingness to fight, and was picked to command the colonial forces besieging Boston.

From 1775 to 1783, Washington oversaw a war that stretched from Savannah, Georgia, to Quebec. He had to deal with untrained troops, unpaid officers, and inadequate supplies; he lost more battles than he won. But he mastered the principles of warfare in North America (the military historian John Keegan ranks him as a strategist with Ulysses S. Grant). Equally important, he kept his often unhappy army obedient to civilian control.

In 1783, victorious, he surrendered his commission to Congress and retired to Mount Vernon.

In 1787 he returned to public life to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia; his fellow delegates unanimously chose him to preside. The wartime structure of government could not deal with the wartime debts the new country had accumulated, and anxious reformers such as Alexander Hamilton and James Madison called for change. But it was Washington’s presence at the convention that reconciled skeptics to its work. He had held more power than any other man in the country, and he had given it up; if he approved the new Constitution, they reasoned, then it could not be a power grab.

The office of the presidency had been created with Washington in mind, and he was unanimously elected to be its first occupant in 1789. But as he took “the chair of government,” he wrote that he felt like “a culprit . . . going to the place of his execution.” He was mindful of the risks of failure, and though his first cabinet was brilliant—including Hamilton (treasury secretary), Thomas Jefferson (secretary of state), and Henry Knox (secretary of war)—and his first term prosperous and peaceful, by the time of his 1793 reelection (which was also unanimous), the country was drifting toward conflict. The western frontier was filled with angry, often violent, tax protestors who resented the whiskey excise; the French Revolution had plunged Europe into ideological upheaval and an Anglo-French world war. In 1794 Washington sent an army over the Alleghenies to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion: if “a minority . . . is to dictate to the majority,” he wrote, “there is an end put at one stroke to republican government.” In 1795, he signed a treaty settling outstanding differences with Great Britain, over the protests of Francophiles such as Jefferson, now in opposition.

Washington’s final political act was to decline to seek a third term, which he would certainly have won. His farewell address (1796), stressing national unity and an independent foreign policy, was his political testament. He died, of a sore throat, at Mount Vernon on December 14, 1799.

The American Revolution, first of the modern revolutions, was one of the few that did not end in anarchy or despotism. Washington, who was at the center of events for twenty-four years, was the man most responsible for its success. His colleague and critic Thomas Jefferson admitted as much. Washington had “the singular destiny and merit,” Jefferson wrote in 1814, “of scrupulously obeying the laws through the whole of his career, civil and military, of which the history of the world furnishes no other example.”

Further Reading

Richard Brookhiser, Founding Father: Rediscovering George Washington

Joseph J. Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington

George Washington, Writings

This entry was originally published in American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia, p. 900.