Debating English Music in the Long Nineteenth Century

By John Ling

(Boydell & Brewer, 2021)

Whilst the phrase “The Two Cultures” will mean nothing to most readers under fifty, it once equaled the international fame of the novelist, physicist, and chemist who in 1959 devised it: C. P. Snow. Snow had in mind the social and intellectual cleavage afflicting 1950s Britain—far more than it ever afflicted continental Europe—between, on the one hand, its science-trained mandarinate and, on the other, its humanities-trained mandarinate.

But Snow could with equal justice have regretted another, albeit much less obvious, cleavage: the gulf between the classical music which gets recorded and the classical music which gets performed in concert. In no field has this gap—already present in 1959, though very much more marked today—become bigger, or sadder, than with British music of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The spectacular expansion of recorded repertoire during the pre-streaming golden discographic age between 1990 and around 2010 (bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, but to be buying CDs was very heaven) achieved the beneficial effect of revolutionizing much musical historiography, concerning British composers above all.

Once almost every piece by figures hitherto seldom recollected outside textbooks—Sir Hubert Parry, Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, and Sir Granville Bantock among them—had appeared on CD in authoritative interpretations, the result was to expose great tracts of hitherto respected critical commentary regarding these names as having constituted mere specious guesswork, no more reliable than Lytton Strachey’s sophomoric approach to eminent Victorians, and not even as well written.

Still, how sadly limited an impact later, better scholars had upon day-to-day concert life, in Britain as elsewhere. An inverse relationship seems to operate between the generous recorded coverage on disc of such hitherto unheard British composers as Sir George Dyson, Sir Hamilton Harty, Sir John B. McEwen, Edgar Bainton, Hamish MacCunn, Cyril Rootham, Dame Ethel Smyth, Rebecca Clarke, Madeleine Dring, and Ruth Gipps, versus the likelihood of these composers’ output being heard in live performance. Even current feminist sensitivities have scarcely improved the four last-mentioned artists’ chances of adorning concert programs in Britain or in any other Western land.

Since this inverse relationship is unlikely to change soon, anyone concerned with British music must simply cope with it, taking care to seek out as much of the relevant music as possible.

Debating English Music in the Long Nineteenth Century indicates, by its arrival, that serious scholarship on the topic has come of age. London-based John Ling, whose doctoral dissertation this book reworks, is altogether free from meretriciousness. His study of primary sources is exceptional—so exceptional that now and then he gives the impression of having been the relevant databases’ prisoner rather than their master—and his fact-filled verdicts are temperate.

Even those of us who have researched British musical history for large parts of our adult lives will find that Ling sheds new lights on the subject and has made connections which we omitted to notice.

Ling’s title is well chosen, since the long nineteenth century’s debates about what British music was, and what it should have been, never really ceased. (While his cut-off date for primary sources is 1907, the outcome would have differed little if he had imposed a cut-off date of 1914 instead.)

As he admits, commentators during this period repeatedly used “England” where, as the contexts confirm, they often meant “Britain”; this review will take the same approach. (By a parallel procedure, many writers used “Germany” when they meant “Germany and Austria,” and thereby felt able to include the Austrian resident Bruckner in volumes with titles like Masters of German Music.)

Whatever party lines musical journalism took amid the relevant epoch—pro-Wagner, anti-Wagner, pro-Verdi, anti-Verdi—one irksome fact nagged at the journalists themselves: England’s fitful record after 1800 in producing native music, compared with its splendid record in producing native literature. The description of England as “the land without music”—das Land ohne Musik, as the original German has it—appeared in a 1904 travelogue by a certain Oscar Schmitz, but Schmitz by no means invented the accusation, which a compatriot of his had published back in 1866.

Where was the English composer of an international stature comparable to that of Wordsworth, Byron, Keats, Shelley, Coleridge, Macaulay, Carlyle, Dickens, Thackeray, Trollope, Sir Walter Scott, Jane Austen, Elizabeth Gaskell, and the Brontës?

Even after revisionist scholarship has done its commendable best in restoring Britain’s post-1870 composers—the Parrys, the Stanfords, the Bantocks—to their rightful place in historiographical surveys, there remains no doubt that for the first two-thirds of the nineteenth century, native English music struck a bad patch.

What caused the bad patch (perceptible, as Ling notes, by the French historian Élie Halévy and by the Belgian musicologist F.-J. Fétis no less than by locals)? Cromwellian Puritanism’s legacy? Stupid aristocrats? Manchester liberalism? The lack of a Continental-type conservatoire network? (London’s Royal Academy of Music, founded in 1822, soon closed despite the Duke of Wellington’s backing.) Too much Wagner? Too much Mendelssohn? All of the above? Could the bad patch have been evaded?

On the answers to these questions, polemics raged. To some extent they rage still. Yet back then the battles had all the charm of immediacy. A nation with an empire that controlled half the globe should have been able to nurture as many first-rate composers as it wished. But it hadn’t, and many English polemicists wanted to know why.

The mindset that subsequent ages called “identity politics” figured in their discourses—the later the article, the sharper the nationalist edge it tended to display—and took, on occasion, guises all too identifiable from later periods. “Much of the argument,” Ling observes, “revolved around the distinctive character, if any, to be expected of English music.” (A revelation from Ling’s account is the role played by, of all things, the 1855 Limited Liability Act in reducing the risks involved with investing in operatic productions. The risks nevertheless remained: in 1864 a London opera company depended on “the popularity of a one-legged dancer” to stave off ruin.)

In 1848, one magazine decried “that fatal imitative spirit, the fruit of which has hitherto been the production of pseudo-German music by British composers”; three years later another magazine mocked the Society of British Musicians as “that miserable burlesque of unity.” In 1868 we find the Anglican clergyman H. R. Haweis flatly stating: “England is not a musical country.”

Ling’s sources are the work of bookish men sometimes educated in Europe, usually well traveled in Europe, and often fluent in more than one European language. These men could be faulted for lapses into aesthetic conservatism of the least intelligent sort. Too many of them continued to denigrate Wagner’s genius long after that genius had won over the greater English public. One critic, Joseph Bennett, memorably warned: “Let us take care that neither in toad-form nor any other does he [Wagner] sit at the ear of the fair art-world, pouring therein sophistries to work irretrievable ruin.”

That said, to compare the cultural literacy that such arbiters could assume in their readership with the populist twerking of Norman Lebrecht’s diatribes in our own time is to dent the optimism of even a Pollyanna. The same Bennett paragraph just quoted alludes elsewhere to Paradise Lost, in the automatic expectation that his audience would at least have heard of Milton. When in 1901 Ernest Newman, then correspondent for a weekly periodical called The Speaker, took it for granted that his audience had read Walter Pater’s Marius the Epicurean, neither his editor nor anyone else at the time thought this belief strange.

Not long ago a supercilious article in Britain’s Musical Times, discussing Ling’s book, railed against these men’s “elitist” attitudes—in just 1,576 words the reviewer managed to use “elitist” on four occasions and “elitism” twice. Wearily we must speculate as to why “elitism” must be considered a mortal sin; how it could have been avoided, even supposing that avoidance had been self-evidently desirable; and whether an age where Lebrecht can flourish possesses unmistakable legitimacy in reprehending the early Victorians’ approaches to high art.

Much of the problem with early Victorian music (Ling might profitably have emphasized this) lay in its habit of excelling at forms that lacked wider European salience. Early Victorian composers frequently lavished their best work on Anglican cathedral music, which in its very essence is about the least exportable artistic genre in all British history, save perhaps for The Benny Hill Show. In this genre Samuel Sebastian Wesley, collateral descendant of Methodism’s founder, shone.

Blessed with fine craftsmanship, an unfailing ear for the niceties of church acoustics, and exceptional talents for appropriate word-setting, Wesley enriched the liturgies of Anglicanism as few have done before or since. But putting Wesley (born 1810) alongside his greatest European coevals—Mendelssohn, born 1809; Chopin and Schumann, both born 1810; Liszt, born 1811; and Wagner and Verdi, both born 1813—prompts comparisons that leave Wesley at an inevitable disadvantage.

With another gifted English composer, Sir William Sterndale Bennett (born 1816), the result is identical. Which returns us to square one: what did go wrong in England?

We cannot rule out the element of sheer bad luck, an element odious to Grand Determinist Theories of Everything. The surviving works by George Frederick Pinto, who died before his twenty-first birthday in 1806, indicate what English music lost through Pinto’s failure to reach a decent lifespan. It is curious, and suggestive, that Spain’s musical history follows a pattern remarkably similar to England’s: glorious native achievements in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; creditable native achievements in the eighteenth; and virtually nothing in the first half of the nineteenth, except for one isolated prodigy of composition, Juan Arriaga (who expired in 1826 at the same age as Pinto). Then, around 1890, there appeared a sudden crop of outstanding Spanish composers—Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados, Manuel de Falla—slightly after the emergence of Parry and Stanford in England.

The nineteenth century’s first six decades were musically disappointing elsewhere too: Scandinavia (apart from the maverick Swede Franz Berwald); Russia (the great compositional efflorescence there—Mussorgsky, Borodin, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, et al.—began only about 1870); and the U.S. (no American composer of the period mattered as Emerson, Longfellow, Hawthorne, Thoreau, Melville, Mark Twain, and Josh Billings mattered).

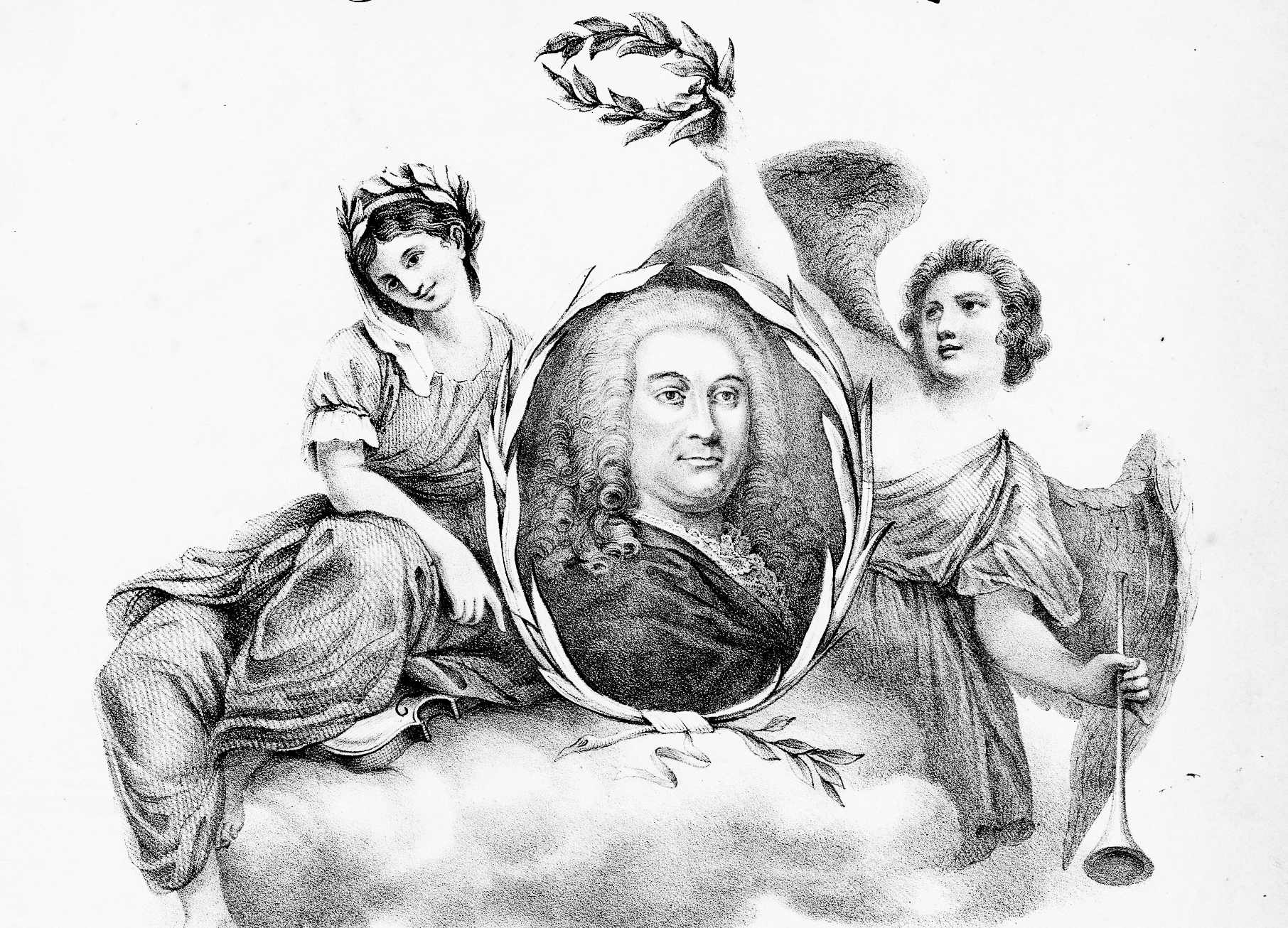

Scholars of economics refer to “the Adam Smith Problem”; unavoidable in any discussion of early Victorian music is what we can analogously call “the Handel Problem.” The astounding popularity of Messiah and a few other Handel oratorios in England until World War II has usually been interpreted as a dead weight on English composition.

This idea seldom bears close analysis—one notable aspect of nineteenth-century English music is how little it is marked by Handelian influence, except when its composers undertook conscious pastiche, as with the aria “This helmet, I suppose” from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Princess Ida—but the idea’s longevity says much about historiographical attitudes.

Ling supplies plentiful quotations to show that many nineteenth-century English commentators regarded Handel’s “manly sentiment” (the phrase comes from an 1820 essay) as an edifying corrective to Latinate musical decadence. Though this view would have astonished the Italophile Handel himself, it persisted for decades.

The Handel-loving English market, above all the English choral-society market, inspired three eminent foreigners—Gounod, Dvořák, and Saint-Saëns—to produce oratorios and cantatas which today are almost never heard, but which in the late nineteenth century enjoyed a huge following.

Dvořák at one stage even contemplated setting Cardinal Newman’s “Dream of Gerontius” to music; soon he providentially abandoned this scheme and left the field clear for Elgar’s masterpiece to the same text.

Much earlier, Mendelssohn had written Elijah for England’s audiences, not for his homeland’s; and, ever since, Elijah has been more often performed by English forces than by Teutonic ones.

In any case, by 1900 London musical journalism’s doomsayers were in retreat. No one before the 1880s predicted that Parry, Stanford, and Elgar would emerge to delight Continental, as well as British, audiences. Equally, no one before the 1880s predicted that England would at last start providing serious higher education for singers and instrumentalists as well as composers, chiefly through such institutions as London’s Royal College of Music.

At mid-century, the whole notion of British governments (as distinct from individual British politicians) supporting musical activity had appeared to be an unconscionable defiance of Cobdenite free-trade principles. By 1890 a general conviction had arisen that British governments should do something, given France’s and above all Germany’s success in treating conservatoire tuition as a National Greatness Project. (Teutonic prowess in the sciences provoked still more fervent English dread. As the Australian mathematician and historian James Franklin pointed out, “English angst about German dominance in music appears to be contemporary with English angst about German dominance in relativity, algebra, chemical warfare etc.”)

Of course musicians griped about the miserliness of official patronage; they always will gripe, and doubtless they always have griped. For Brendan Behan, there existed “no such thing as a large whiskey”; for us musicians, there exists no such thing as ample government largesse. But anyone who examines Ling’s later chapters after his earlier ones can tell how the overall atmosphere of English music had gradually changed, almost beyond recognition, between 1800 and 1900.

Even after Ling has done his archival utmost, we still cannot be sure why British composers were attaining so much greater heights in 1900 than they had in 1850. The increased professionalization—and social respectability—of musicians’ careers must have played a vital role; vanished were the days when Parry could obtain his bachelor’s degree in music while still an Eton schoolboy.

Royal patronage of good music also helped: the Prince Consort stood no nonsense from half-educated peers who begrudged every shilling spent on orchestras and choirs rather than on blood sports.

Ultimately, though, trying to foretell the advent of outstanding composers is as chancy a business as betting on horse races. Who in mid-nineteenth-century Finland could ever have prophesied a Sibelius? Who in mid-nineteenth-century Norway a Grieg? “The wind bloweth where it listeth”: a truth that some of the more sanguine and scientistic pundits in Ling’s narrative would have benefited from avowing.

Melbourne-based organist Robert James Stove is the author of César Franck: His Life and Times.