Tom Stoppard: A Life

By Hermione Lee

Knopf, 2021

George Bernard Shaw said that Henry Fielding was the finest English playwright since Shakespeare. It was not an unreasonable claim. Studded with great lines, Fielding’s best plays are cleverly plotted, highly original and consistently entertaining. More, their characters are subtly drawn and thoroughly real, and the stories shift from laughter to pathos with rapidity and grace. Yet Fielding’s plays were nearly unknown by Shaw’s day, and they are almost never performed today. That raises the question of why seemingly superior dramas disappear from the repertory and what theater is most likely to endure.

That’s at issue with the publication of Hermione Lee’s new 872-page biography of playwright Tom Stoppard. Equally relevant is the matter of whether any writer who has lived a civil, upright life is an ideal subject for a volume that is longer than Bleak House. It will take you more time to read than you would expend in consuming all of Stoppard’s best dramas.

Lee has done her job with doggedness and uncommon intelligence. She is tactful in describing untoward events and penetrating in her analysis of Stoppard’s work. Even so, the quantity of detail is overwhelming. Within the first few pages you find out the precise street number of a house that his parents lived on and the identity of a retired arts administrator who may (or may not) have been delivered by Stoppard’s doctor father. Through the rest of the massive tome, there are hundreds of such bits of minutiae.

Does Stoppard merit such a doorstopper? While I am a great admirer of the Czech-British dramatist, and have even been an imitator of him, I do not think this necessarily means that his plays will be central to the theater repertory a century from now. For Stoppard’s weaknesses are sometimes as notable as his strengths. In particular, one might point to:

Lack of popular appeal. Stoppard has written hit movies. This includes his co-authorship of “Shakespeare In Love.” Yet few of his plays have quite made it with the broad mass of the public. I’m a playwright myself, and I can say with confidence that the New York production of “The Invention of Love” was the best new play production I have ever seen. But I noticed that a lot of the audience was left unmoved. They simply didn’t get it.

Characters with little or nothing at stake. It’s been said that “Night and Day” is the only Stoppard play in which the main character is knowingly presented with a life-and-death decision. That absence lowers the boiling point and the dramatic tension.

Lack of three-dimensionality in the central characters. Many of Stoppard’s characters don’t seem like people who exist off-stage. We have no sense of where they come from or why they became who they are. The play that won him his fame, “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” is actually about off-stage characters.

The last criticism matter may be the most serious. There is no Willy Loman, Blanche Dubois, or James Tyrone in Stoppard’s oeuvre. And, as Arthur Miller observed, plays survive more because of their roles than their intrinsic excellence. Indeed, that is the principal reason that Fielding’s dramas have been forgotten. There can be other causes, of course. Political dramas date quickly. Thus, while twenty years ago Athol Fugard’s plays were talked about as undoubted classics, once apartheid disappeared so did Fugard. Likewise, it’s a safe bet that Tony Kushner’s work will be unremembered soon after his passing.

That won’t be an issue with Stoppard’s plays. So will they stand up? I think we can very safely say that they will. His work has unusual qualities that far exceed their deficiencies. It isn’t only that they are stuffed with the most extraordinary wit. Possessed of a surfeit of charm, he can be profound without ever being stuffy. We laugh and enjoy ourselves as though we were watching the slightest French farce even as Stoppard leads us through an exploration of the grand questions of life. Tickling us with a feather, he leads us into an inquiry about whether routine existence matters (“Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead”), if we should we have faith in God (“The Hard Problem”), whether math can illustrate the chaos inherent in our personal destinies (“Arcadia”), or how to face the fact of unrequited love (“The Invention of Love”).

Even in a lesser Stoppard play like “Rock’n’Roll,” the playwright manages in affecting fashion to show how totalitarianism leads to needless cruelty: an underground record collector returns home one day to find that his hundreds of beloved long-playing record albums have been demolished by the state security police. Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away, an intellectual suddenly observes that the genes which gave rise to his facile intellect have skipped a generation, going from his flibbity-gibbet daughter to a grandchild he barely knows. Stoppard is able to dramatize vital questions without recourse to heavy-handedness, melodrama, cheesiness, or cliché. A very good case can be made that he has surpassed Shaw (and Fielding, for that matter) to assume the mantle of being the outstanding comic playwright in our language.

But that still doesn’t answer the question of whether he is a welcome subject for an almost 900-page biography with more details than can be found in a baroque cathedral. Great historical personages—Napoleon, Lincoln—are ready subjects for monumental studies as they stand at the fulcrum of world changes. By contrast, though literary figures can be delightful dinner party companions, their significance lies in their writing, which ought to be open to reading without a mass of exegesis. I can only think of two literary biographers whose work compares to the best historical ones: James Boswell and Richard Ellmann.

Boswell has survived not only for the excellence of his style but because he preserved a multitude of pithy and memorable observations of Dr. Johnson. In writing about Oscar Wilde, Ellmann had something most unusual: a literary figure whose life possessed high drama. That Wilde has come to be seen as a martyr gave his story added significance, and it’s interesting to learn from Lee that Stoppard was heavily influenced by it in writing “The Invention of Love,” as he had earlier made use of Ellmann’s biography of Joyce in composing “Travesties.”

The commencement of Stoppard’s life had considerable drama. Born in 1937 in what is now the Czech Republic as Tomas Straussler, he was taken by his mother, along with his older brother, Petr, to Singapore and then to attendance at a church school in the hill country of northern India. They were in flight from the Nazis. Along the way, Stoppard’s parents were separated, and his father was killed on a ship strafed by the forces of Imperial Japan. When his widowed mother then remarried, to a British army major, the little refugee was brought to England. With the move, there came not only a new life but a new name.

Stoppard only learned that his mother was Jewish and that most of his family had perished in the Holocaust during a visit to the Czech Republic in 1995. He was in late fifties then. He was already keenly aware that Britain’s traditional political forms and ways of life protected and preserved his own. That knowledge made him a conservative, and his views awakened considerable hostility among the chattering classes early in his career. He has managed to still the waters through some mix of persistent achievement and amiability.

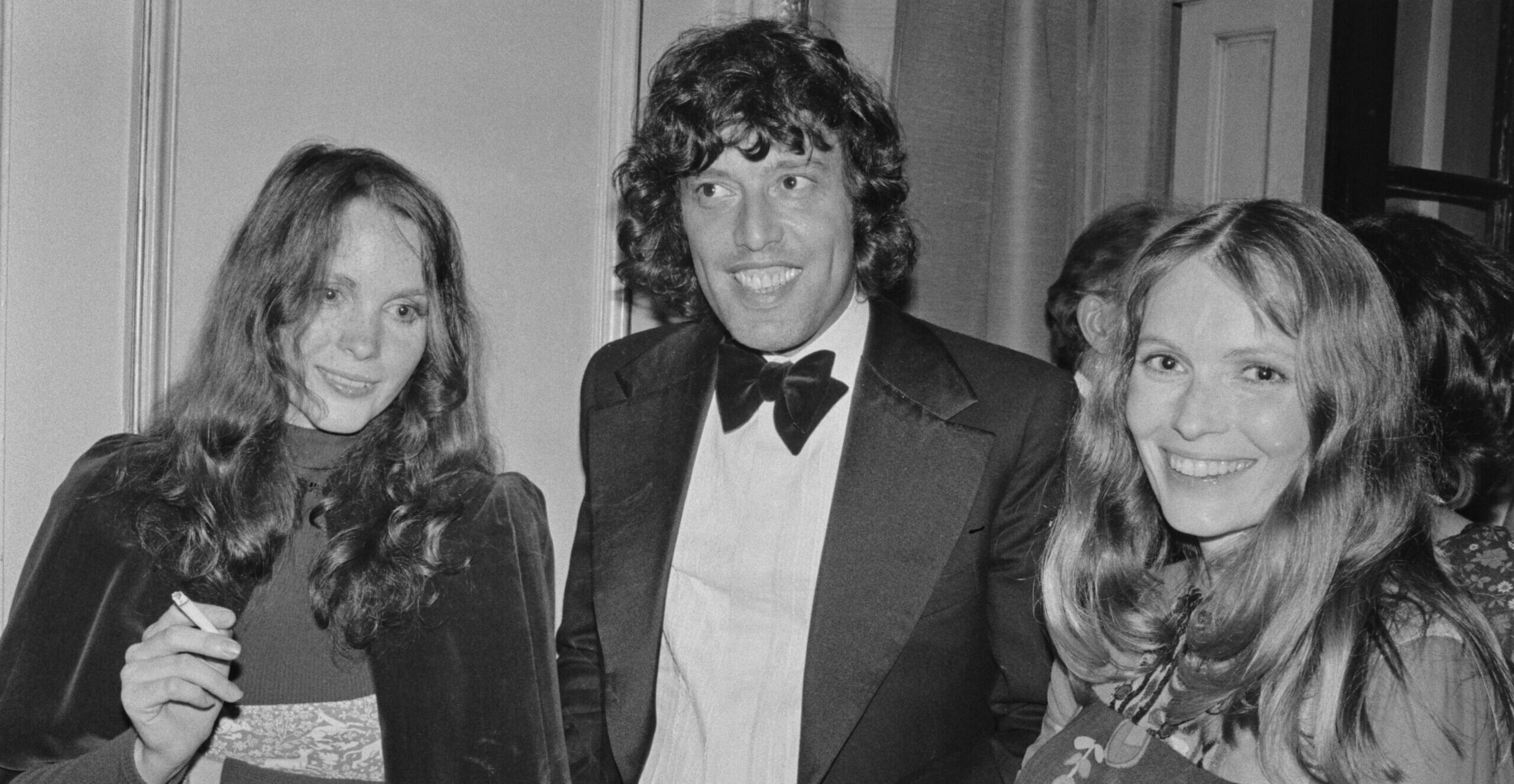

Lee makes use of the drama in Stoppard’s life in telling her story. She has also been given access to his personal letters, and she demonstrates a novelist’s skill in depicting the complexities of her many characters. This includes not just Stoppard but his three wives, three siblings, four children, and many others. Lee is also a sensitive critic, and she has a deft touch in noting when Stoppard’s work has fallen flat, as with his convoluted spy drama “Hapgood.”

Tom Stoppard: A Life is impressive and a vast improvement on the earlier biography of Stoppard by Ira Nadel. Stoppard-lovers will greatly enjoy it. Everyone and everything pops up in its pages. Two-thirds of the way through I happened to learn that Stoppard’s third wife’s brother is married to the sister of an old friend of my own sister. (Full disclosure.) It’s that kind of book. If you have lived in New York or London in the last forty years and met a few of the famous, you’ll see at least one name you know on its pages. I’d still recommend you sit down and read Stoppard’s plays before you pick up this hefty volume: consider that while Lee does an excellent job analyzing “Arcadia,” her more than forty-page discussion of it is longer than the play.

Jonathan Leaf is a playwright and critic living in New York.