Although the eleven essays comprising Dictatorships and Double Standards were written over a period of twenty years, they share one concern. The subtitle defines it as rationalism vs. realism in politics; in the introduction, it is freedom vs. unfreedom; here and there throughout the book it is Aristotelianism vs. Platonism. These antitheses combined produce the recurrent argument of the book: Platonic rationalism is to unfreedom as Aristotelian reason (meaning reasonableness) is to freedom.

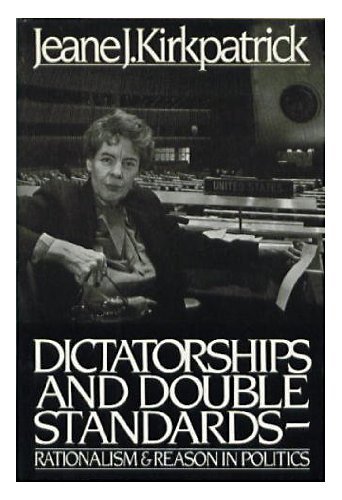

The main title is therefore not indicative of the contents. “Dictatorships and Double Standards” is the title of the article in Commentary that, as everyone knows, led to Mrs. Jeane J. Kirkpatrick’s appointment as Ambassador to the United Nations. This essay is the first of five in the section “Rationalism in Foreign Affairs.” The remaining six essays comprise the section “Rationalism in Domestic Affairs.” Conservatives should read all eleven carefully, for they show the grounds and the limitations of the alliance between conservatives and those whom the left calls “cold-war liberals.” Mrs. Kirkpatrick is a “cold-war liberal,” strongly anti-Communist in foreign policy and equally strongly pro-welfare-state in domestic policy. Conservatives who are unclear about their allies’ views could entertain illusions about how much support they might expect on domestic issues.

The essence of “rationalism” in the context of this book is “the effort to make institutions conform to abstract principles.” This approach to politics

assumes that institutions and people are more malleable than they are. Not only does the rationalist approach to politics aim at replacing custom with purpose, but it almost always operates from an oversimplified conception of social process and fails to take adequate account of possible resistance to the desired goal and of the effects of interaction and of cumulative impact. In consequence, reforms inspired by the rationalist spirit are especially likely to produce utterly unintended consequences.

Except for the reference to abstract principles and the counterposing of custom to purpose, the passage could have come from the pen of a conservative. The reader might even expect to find a citation of Professor Michael Oakeshott’s Rationalism in Politics, published sixteen years before those words were written. Yet Mrs. Kirkpatrick not only omits all mention of that book but also calls “the New Right,” along with the McGovernite Democrats and the practitioners of Carterite foreign policies, rationalistic.

In foreign affairs, she explains, Carterite rationalism meant the abandonment of belief in the moral legitimacy of the American national interest and of its defense. Concern for abstractions such as “human rights,” “development,” and “fairness” was always implemented in terms favorable to socialist regimes, terrorists, and guerillas. And since, as Mrs. Kirkpatrick reiterates in both sections of the book, the best is the enemy of the good, all regimes perceived as permanently imperfect were denounced as wholly evil. The Carter administration helped to depose governments friendly to the United States and to install hostile ones; never did it try to destabilize a Communist regime. It judged totalitarian movements by their theories, and our allies by their practice. Repeated proofs, throughout history, of the vicious consequences of this way of thinking had no effect, for the rationalistic mind is impervious to evidence. It is also utopian, and “Totalitarianism is utopianism come to power.” Utopians condemn people as they are, name environmental determinants for the faults in human nature, and assign to a privileged elite the power to interpret reality—all reality, not just politics and economics but also culture, down to the most intimate aspects of people’s lives.

So far so good. It is when Mrs. Kirkpatrick shifts her attention to domestic politics that conservatives should find cause to disagree with her analyses. In fact, the logic and principles she uses to criticize the Carter foreign policies could be turned on her own domestic policies. This is not to deny that the book contains profound insights and has much to teach us. I shall give little attention to the good things in it, however I prefer to use the space allotted to me to discuss aspects of the book not likely to be stressed in other reviews that readers of Modern Age will have seen. The next three paragraphs are a brief summary of some of the author’s principal arguments concerning domestic politics.

Rationalists, hostile toward the traditional political parties, forced the Democratic National Convention to disregard the composition of the party’s constituency and to choose delegates according to racial and sexual quotas. Presidential primaries also helped to weaken party organizations and shift the spotlight and power to individuals with access to the media and money. The same thing has been happening with the Republican party: the party-destroying McGovernites among the Democrats have their counterparts in the New Right among the Republicans. Once in power, these reformers, who have few constituents, impose their utopian schemes on the nation, but the results are often not what their Platonic blueprints intended. Real life does not, however, deter them, for they are cut off from it; they have no roots in traditional communal institutions. They prize consistency, whereas the average American will vote conservative on one issue, liberal on another.

In the long run, practicality will prevail. Americans will not choose equality over liberty, as the left wishes, or liberty over equality, as the right wishes. When liberty and equality are not pushed to extremes, they are interdependent. The reasonable middle way between left and right, the politics that realizes the greatest liberty and the greatest equality, is “the contemporary welfare state—sometimes known as ‘bourgeois democracy.’” This welfare state inherits the tradition of the Founding Fathers, whose Constitution was neither a Platonic blueprint nor a natural product of evolving institutions. It was deliberately designed to achieve explicit goals. The Framers saw their task “as a great opportunity for social engineering.” “The principle of the separation of powers” was “a device basic to the constitutional engineering of the Founding Fathers,” and the moderate beliefs about human nature are “the basis of the national attitude toward social engineering, of which the Constitution is a quintessential example.”

Social engineering having been thus legitimized, it follows that the heirs of the Founders’ tradition are those who now want “to eliminate through regulation the most important abuses of the capitalist system.” They have passed laws governing the terms and conditions of employment, collective bargaining, securities and trust regulation, graduated income taxes, and social security systems, and other reforms. If not for their work, child labor would, one infers, still be with us, and workers would be at the mercy of their employers. Restrictions on employers’ freedom of contract were reasonable prices to pay for the increase in the freedom of workers. Just as reasonable are the most recent arguments “now being used to support a new expansion of government’s regulatory power. This time, social rather than economic deprivation is the target: the government is called on to offset disadvantages of sex, race, and age.” But because liberty and equality should be kept in balance, these reforms should not be pushed too far. Whereas affirmative action is good, court-ordered busing is bad. “Freedom from severe economic and social deprivation,” furthered by “providing the basic elements of the good life—hot lunches, old-age pensions, education, medical and dental care,” paid for by government—is good; but the “tendency to see government as responsible for ever larger portions of the individual’s environment and destiny” and “the continuous expansion of government’s jurisdictions and functions,” reflecting “a spreading belief that government action should supersede private social initiatives,” are bad.

The above highly condensed summary suggests the self-contradictions and begged questions that in my opinion undermine Mrs. Kirkpatrick’s argument. The most glaring of these flaws result from her determination to invoke a plague on both the McGovernite left and the New Right houses. (Traditional conservatives do not get much attention in the book.) Between those rationalists of left and right she locates the moderate liberals and neoconservatives—reasonable, pragmatic people who support the welfare state. Because her adversaries are by definition rationalists, she must find New Rightists to be as rationalistic as the radicals. This task is beyond even Mrs. Kirkpatrick’s formidable powers.

Sometimes she criticizes the New Right for committing sins that welfare-state advocates also commit. At other times she criticizes them for committing sins that only the far left commits. For example: “The goal of the new-class reformer—whether of Left or Right—is to bring the real into conformity with the ideal (that is, with an idea of reality).” Conservatives will of course plead “guilty.” But what are welfare-state liberals doing when they pass laws “to offset disadvantages of sex, race, and age”? What else is the “social engineering” for which the author praises the Founding Fathers but should more appropriately ascribe to advocates of the minimum wage, affirmative action, and the graduated income tax? On the other hand, is it true that New Rightists are “rationalistic” and “utopian”? Do they assume “that people and institutions are more malleable than they are”? Are they unaware of the likelihood of “unintended consequences”? Indeed, aren’t these fallacies among the fundamental targets of the conservative—including New Right—criticism of the welfare state?

The “new class” that produces those reforms, says Mrs. Kirkpatrick, is a sociological, not ideological, phenomenon; members of it are to be found at all points on the political spectrum. On the average they differ from most Americans in being professionals, having higher education, making more money, enjoying more prestigious occupations, and often belonging to the more liberal religious denominations. “Party reform, especially the Democratic variant, advanced the class interests of” those reformers. Note the question-begging phrase “especially the Democratic variant,” which tries to maintain the balance between the two extremes. But who constitute the New Right? New Right leaders represent genuine grass-roots constituencies and are usually of lower social and economic status than the left-wing “new class” reformers.

Mrs. Kirkpatrick accurately notes that some New Rightists have lost faith in the Republican party and have toyed with the idea of restructuring the parties to make them represent clear and consistent philosophies. These Republican reformers failed and will continue to fail, she says, because they misread the temper of the American electorate. Why then did the McGovernites, who were even worse readers, succeed? Could it be that the cases are not, after all, analogous? Mrs. Kirkpatrick is, I think, confusing externals with substance and motive. The New Rightists’ tactics were, as Mrs. Kirkpatrick admits elsewhere, reactive and in defense of what the left had been destroying. The radicals succeeded, by ideological intimidation and manipulation, in making the Democratic party reflect their own ideology; the New Right has, rather, been trying to induce the Republican party to defend traditional values. It is simply grotesque to characterize the pro-prayer and anti-abortion movements, for instance, in the same way as their adversaries on the left, as equally “rationalistic” and “ideological.” One might as well contend that a burglar and his victim, who resorts to drastic means to defend his home, manifest the same views of human nature, the same attitudes toward ideas, the same indifference to unintended consequences, the same desire to replace custom with purpose.

Mrs. Kirkpatrick justly criticizes some New Rightists’ tendency to assume “that people who are conservative on one issue are ‘conservatives’” and “that voters are more ideological than they in fact are.” But conservatives would take issue with the word “ideological” in that context. If we say instead that they are not “consistent,” we suggest a different model. If Joe Voter, union member, supports both a higher minimum wage and a reduction in taxes for CETA, is he being commendably ideological or deplorably inconsistent? When someone denounces South Africa for being undemocratic but supports aid to Nicaragua, Mrs. Kirkpatrick does not say he is being pragmatic and unideological. She criticizes him for being inconsistent, for applying a double standard. She approves of efforts to enlighten public opinion on foreign policy, to make it more consistent, but on domestic policy she accepts inconsistency as normal: “The New Right belief that the large majorities who support traditional values and practices would vote conservative in presidential elections if only the conservative candidate provided adequate leadership” is wrong because elections do not offer clear-cut choices.

The same criticism may be made of Mrs. Kirkpatrick’s answers to the question, What caused the parties to weaken? She replies: new issues; less confidence in social and political institutions; TV, which politicians and new-class symbol-manipulators use to make direct contact with voters; “and, perhaps especially . . . the progressive ineffectiveness of the family and other traditional agencies of socialization.” In addition, “the most important sources of party decomposition are the decisions made by persons attempting to reform the parties.” (Note the plural, “parties,” which includes the Republican party.) But what caused the weakening and loss of confidence in the family and other traditional institutions? Nowhere does Mrs. Kirkpatrick include the welfare state among the causes. She does say that “The New Deal brought significant numbers of intellectuals and semi-intellectuals into government for the first time, to solve pressing problems that had eluded solutions.” In recent decades, she adds, the new class has wielded decisive influence in “shift[ing] responsibility for the quality of social life from the individual, family, and other private groups to government.” This is, she argues, not the outcome of welfarism but a departure from its “traditional” form. The New Deal did not set us on the road to the current situation; the rationalistic reformers illegitimately tacked cultural-moral issues onto politics and caused the present political disarray.

The logic is clear: since the welfare state is good, and since the ideologizing, moralizing, and deinstitutionalizing of the parties are bad, the welfare state did not cause them. The reformers on the left are just the newest representatives of the age-old rationalism against which Aristotle polemicized. The New Right version of it “represents a strain of nativist populism whose roots are deep in American history. . . .” (The illogic is clear, too: how can a New Rightist be a populist and also assume, as Mrs. Kirkpatrick says all “rationalists” do, that he “knows better what is good for the people than the people themselves”?) Although some programs of the welfare-state liberals are new, their approach to politics is allegedly traditional and goes back to the Founding Fathers’ “social engineering.”

Mrs. Kirkpatrick’s several discussions of “unintended consequences” of well-meant policies are invariably on the mark. What is missing is attention to the unintended consequences of the liberals’ state-expanding policies. Indeed, she denies that busing is merely a logical extension of school desegregation “or that regulations stipulating the size of toilet seats for employees are ‘only’ a logical extension of the same concern for work safety involved in mine inspection.” Logical extensions they are not; political consequences they certainly are. For, once economic and social questions, hitherto dealt with in the private sphere, are made subjects of politics, consensus will never be possible on where to draw the line. Mrs. Kirkpatrick draws that line according to her own logic: affirmative action is good, although it restricts employers’ freedom, because it increases that of employees who might otherwise not be hired; quotas and forced busing are bad, because they decrease individual liberty too much. But people who want quotas and busing, and people who disapprove of affirmative action, will use other logics. One can always find a principle to ratify what one likes and to bar what one does not. The difficulty of reaching consensus on where to draw the line is sufficient evidence that those latest reforms are consequences of the policies of centrist liberals—consequences they never intended but could not prevent. The chief antecedent of the unintended consequences was the politicization of economic and social decisions. Of course the moderate liberals did not intend coerced busing, quotas, silly regulations, weakening of family ties, psychological dependence of citizens on redistributionist programs, and the other things she deplores. “The continuous expansion of government’s jurisdiction and functions,” she notes with disapproval, “reflects a spreading belief that government action should supersede private social initiative (whether individual or group).” But who expanded government’s jurisdiction and functions? Intentions are not causes, and the absence of intent is not proof of the absence of causal connection. As Mrs. Kirkpatrick herself writes, “No universal abstract principle can mechanically distinguish between caring that sustains and caring that coerces.” Yet her own fine balancing of liberty and equality is just such a principle, and that is why the caring that sustains should not be done by the one institution—government—that monopolizes the right to coerce.

There is, however, one line that can be drawn between justified and unjustified government, a line that people may argue over but that is nevertheless clear. That line is between positive and negative governance. Traditionally our constitutional and legal systems have emphasized the negative: government may not do this or that to individuals, and individuals may not do this or that to each other. Positive requirements have been limited mainly to the obligations of individuals to pay taxes: sit on juries, serve in the armed forces, and educate our children. Since the 1930s, however, reformers have been attacking this preference for negative governance. They began modestly, with such positive requirements as employers’ obligation to negotiate with unions and to pay wages above a certain legislated amount. Inevitably the positive duties came to be matched by the positive “right” by some citizens to receive the fruits of other citizens’ labor. The liberals’ latest requirement, affirmative action, is as inherently unlimitable as are open-ended “entitlements.” The emphasis on negative governance—inconsistent and limited though it was—set us on the road to the greatest economic development in history. The reversion to the omnicompetent state is paying off now in economic stagnation, increasing coercion by government, the punishing of enterprise, the rewarding of idleness, moral degeneracy, and an understandable feeling that our institutions are not worth dying for. That Mrs. Kirkpatrick doesn’t believe in any of these things, she has proven as our U.N. Ambassador and in all the essays in this book. But they are consequences of the legitimation of social-activist politics.

“[I]n those countries where citizens enjoy the widest freedom,” writes Mrs. Kirkpatrick, “ordinary people use collective bargaining and politics to get an increasing share of income, education, leisure, health care, and other available goods.” Precisely: they use politics to get economic goods. Once that door has been opened, not only can it not be shut, but ever more economic decisions are invariably transferred to the political realm. The welfare-state measures that the author favors did more than anything else to further the political-party decline that she deplores. By making those areas subjects of federal authority, welfare-state liberals gave the new-model reformers both the incentive and the opportunity to implement their schemes through the government and, in the process, to buy the votes of the designated beneficiary groups, thereby transforming and bypassing party organizations. This began to happen long before the McGovernites took over the Democratic national convention in 1968. Experience here and abroad revals a natural affinity between welfare-statism and the ideological politics that Mrs. Kirkpatrick condemns. The weaker the private sector is vis-à-vis the government, the greater the opportunity both zealots and thugs have to capture the government. The welfare state weakens the private sector ideologically as well as materially, by promising the end of risk, by making decisions hitherto made by individuals and community leaders, and by making “profit” a dirty word. A vicious spiral has been created whereby the material weakening of the private sector enhances the ideological claims of the reformer, who then use their ideological claims to further weaken the private sector. The difference between the welfare state and Communist totalitarianism is therefore quantitative, not qualitative (if I may use these Marxist terms), for the germ of the latter is already present; that is, the ideological delegitimation of a political opposition. The more everything is politicized, the more superfluous politics becomes.

The most basic objection to the parallelism between the far left and the right and to the overlooking of the unintended consequences of moderate welfare-statism is that majoritarian democracy, linked with the welfare state (history has, of course, known examples of each unaccompanied by the other), creates an appetite that grows by what it feeds on. The evidence is in the news every day. In October 1982 a network-TV news segment showed Vermont apple orchards manned by Jamaicans because unemployed Vermonters refused jobs picking the apples. One man interviewed before the camera said over and over, “I don’t have to take any job paying less than $8 an hour.” The ballet-dancer son of a well-known millionaire refused his parents’ offer of help during a season of unemployment, preferring to collect unemployment insurance because he wanted to be “independent.” Dependence on taxpayers is not dependence; family help is.

What is the minimum security to which the moderate welfare-stater would limit the government’s obligations? Above the level of sheer survival, it is whatever people get used to. The minimum does not define welfare benefits; welfare benefits define the minimum. The point is not that benefits have been too generous. It is that the vast, bureaucratic, tax-supported system in which nobody is responsible is the opposite of private philanthropy in most vital respects: using taxes raised involuntarily from everyone, it destroys discrimination based on need and desert, affords the donors no recourse that would not hurt the deserving along with the freeloaders, disguises dependence as “entitlement” to other people’s earnings, and fosters the illusion that one can order a free lunch—and instant service—and then surprise when one is presented with the bill as an “unintended consequence.” It also gives a blank check to politicians who buy votes with promises of more. That this is the unstoppable logic of the welfare state was proven in the recent election campaign when even conservative Republicans found it expedient to reiterate that the Reagan administration had not cut welfare spending but merely slowed its increase. To Mrs. Kirkpatrick’s thesis that welfarism aims “to eliminate the most important abuses of the capitalist system,” conservatives can reply that it causes abuses that liberals blame on “the capitalist system.” These two hypotheses measure the distance between Mrs. Kirkpatrick’s and conservative political philosophies.

There is, in addition, a more subtle measure in this book. Mrs. Kirkpatrick, who pointedly criticizes radicals’ semantic obfuscation, nevertheless seems not to have examined one of the most common forms of it, the use of certain words and inverted commas that betray a subliminal acceptance of the claims of the left. “Communists in France,” she observes, “attempt to identify themselves with the symbols of the Resistance, the French Revolution, and the tradition of the Left.” As to the latter two, why shouldn’t they? Furthermore, in several places she puts the words “socialism’’ and “socialist” between inverted commas when referring to countries ruled by Communist parties, implying that they are not really socialist. In another place, she asserts that the counterposing of liberty and equality is “a familiar justification for tyranny in many new nations and so-called socialist states. . . .” Why the “so-called”? Behind these seemingly trivial practices lurks the unexamined equation of socialism not with its program but with its professed ideals. But the essence of socialism is not the promise of peace, affluence, security, brotherhood, equality, and justice, most of which goals are shared by nonsocialists. Its essence is its program of nationalization of the means of production, abolition of the free market, concentration of both economic and political power in the hands of government officials, and—in those countries in which this program has been carried out thoroughly—tyranny. This is not 1933, when reasonable men might have said, “The socialist program has not been tried long enough and in enough countries to prove that it is not the means to its professed ends.” This is 1983; by now the full socialist program has in every case produced tyranny, and the partial socialist program has in every case produced declining productivity, destruction of incentives, enormous deficits, inflation, unemployment, and social disintegration.

These verbal quirks would not deserve much comment if they did not serve the logic of Mrs. Kirkpatrick’s demarcation of her own welfare-state liberalism from the left and the right. The great delusion of our time is no longer Communism but the belief that the majoritarian-democratic welfare state has nothing in common with Communism and, as some even argue, is our best defense against it.

Mrs. Kirkpatrick sees no inconsistency between her positions on foreign and on domestic policy. But conservatives should not be satisfied merely to point out the contradictions between them. Our philosophers have written copiously on political philosophy, and our journalists have written copiously on practical politics. But the area where these twain meet needs more systematic thought than we have given it. That area is the middle ground where the most abstract and the most concrete overlap, where emotional preference for a policy should be informed by general principle applicable to an immediate issue, but where the general principle cannot be translated directly into political action. It is to be hoped that our scholars will write their own versions of Dictatorships and Double Standards. The inconsistencies and lacunae in Mrs. Kirkpatrick’s book augur success for our efforts to show that a single set of principles can inform our positions in both areas and that our alliances and compromises, inevitable in politics, can be both realistic and conformable to our values, in both areas. By filling that gap, conservative political thinkers will clarify the nature of our practical alliance with nonconservatives, give more guidance to our own practical politics, and save us from those unrealistic expectations that many of us had in November 1980. In Mrs. Kirkpatrick’s case, conservatives should be grateful for the inconsistency of the champion of welfarism at home who has fought against its unintended—and in many cases intended—consequences abroad.

Aileen S. Kraditor was a professor of history at Boston University and the author of a number of books on feminism.