Alexis de Tocqueville was encouraged by what he saw in the United States of the early nineteenth century. America was a democracy in which the people’s needs were met by their own local, self-organized “associations” of all kinds, not by an all-provident centralized authority. Equality did not mean social atomization and dependence upon one great unequal power, the state itself. American democracy was neither mob rule nor the equality of pupils under a master.

Yet Tocqueville was not at all certain that this kind of self-government would survive in the long run. He had many practical grounds for concern, but the root of his doubt was to be found in human nature itself. To continue ruling themselves, Americans would have to persist in taking an interest in politics. But the very freedom they enjoyed gave them the opportunity to turn to private pursuits instead, leaving higher levels of government to do for communities what active citizens should have been able to do for themselves. Over time, government at every level has in fact become something millions of Americans are content to leave to the experts: professional bureaucrats and policymakers.

Tocqueville had seen—and eventually described in The Old Regime and the French Revolution—how the nobles responsible for local government in France had given up their duties to the communities in their care to lead lives of greater luxury in Paris and at court instead. To take their place in the country, the king of France appointed new officials answerable directly to him. Some thing similar could happen in America: if French aristocrats willingly gave up the burdens of responsibility for a life of ease in the capital, wouldn’t American democrats sooner or later give up self-government for the comforts of private life?

In the modern world freedom begins in virtue and ends with utility. To oppose a tyrant requires great courage, and a liberator risks his life for the good of others. As long as freedom is an aspiration, it inspires selflessness and the highest human virtues. But freedom has a different character once it is securely obtained. Instead of a single noble goal—the defeat of a wicked ruling power—freedom once in hand comes to be defined by the lack of any clear aim: it means everyone can do anything he or she wants, and every desire becomes equal. Tocqueville already saw this tendency in democratic equality nearly two centuries ago.

Because qualitative political distinctions between different personal aims are generally disapproved in a modern egalitarian democracy, distinctions are instead justified by quantitative measures. These include not only the obvious quantitative rule of greater numbers in elections but also, and more profoundly, the quantifying of the human good itself in the form of money. Whatever makes money will be perceived as good, while what makes less money—or loses money—must be bad; after all, money is simply a stand-in for the multitude (and scale) of human aims and desires.

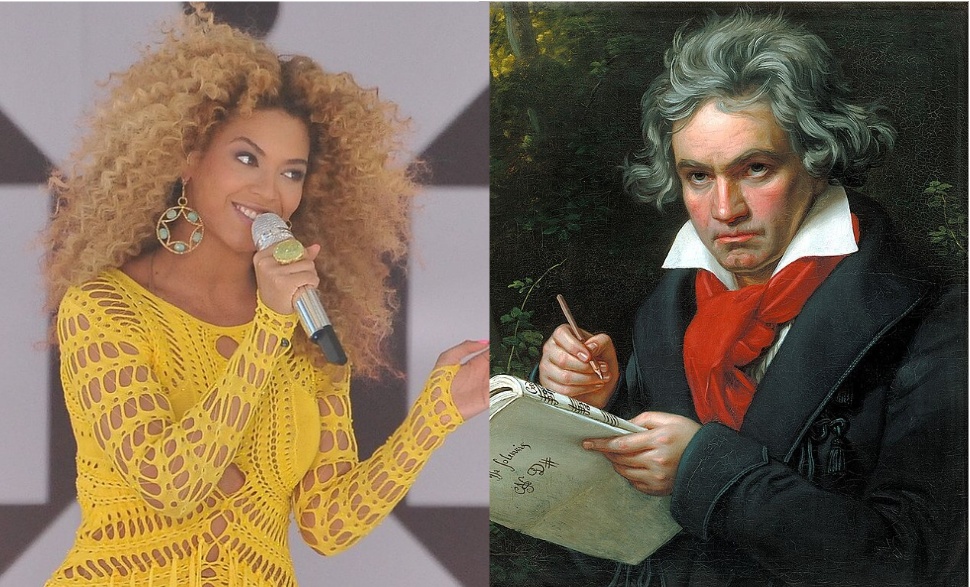

King Numbers not only prevails in elections but in the marketplace, too, and little by little in the realm of cultural status. Today many Americans are outraged by the suggestion that Beethoven might be “better” than Beyoncé. What could justify such a claim, other than sales data? (In fact, even sales don’t necessarily settle an argument on these terms, since numbers and dollars don’t always trump the underlying cultural presumption of equality.)

In the cultural realm, and in morals too, democratic equality levels the good and the bad. The only thing that remains truly bad is whatever is more-than-equal or gets deemed undemocratic. The good is increasingly understood in utilitarian terms, not only as what satisfies the greatest number but also as the most efficient means toward producing subjective satisfaction. The result is that human beings become uncertain about what ends to pursue, but they know that they must prioritize making as much money as possible in order to succeed. Americans can no longer agree on whether a man is a man or a woman, but they are united in recognizing the importance of a good career. Sex is controvertible; utility is not.

Tocqueville feared what would become of the virtues associated with nobility in a regime of democratic equality. He despised despotism, including the new democratic despotism that he saw on the horizon, in which a busy, hedonistic people gladly surrenders the burden of self-government. But his reasons were ethical, rather than arising from a reflexive hatred of statism. What made human beings noble and good could be lost—men could forget their own souls.

As important as elections and economics certainly are, the conservative’s primary task is to remember what makes us human. Democratic self-government of the type that Tocqueville admired calls for engaging with other human beings not as numbers but as persons, in all their incommensurability, which is one reason why it is most readily practiced locally. This democracy and the freedom that attends it cannot supply a single, unifying human end—not even resistance to tyranny. But it’s a democracy that puts personhood above utility, and friends before means.