Since 1976 Modern Age has been published by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute. But when ISI began seventy years ago, its educational mission was narrower than it is today. What began as an ambitious initiative to counteract socialism on America’s campuses evolved into an organization whose mission is to educate for liberty in the broadest sense, preparing future generations for the responsibilities of freedom by acquainting them with the profound moral and civilizational patrimony to which they are heir. As Modern Age celebrates ISI’s seven decades, we present Lee Edwards’s account of ISI’s founding and founding fathers. —ed.

Frank Chodorov tilted against windmills all his life. As a student at Columbia University in the early 1900s, he fought the socialists, arguing that “man’s management of man is presumptuous and fraught with danger.” He voted in 1912 for the independent Theodore Roosevelt rather than the Democrat Woodrow Wilson or the Republican William Howard Taft. He never voted again, declaring that politics was the problem, not the solution.

Born in New York City of immigrant Jewish parents, Chodorov turned to atheism as a young man, stung by antisemitic remarks at Columbia. He asserted that religion was “at the bottom of social discords.” In his later years, however, he came to believe in what he called “transcendence,” even writing an essay titled “How a Jew Came to God.”

He said the income tax was the root of all evil and took up the philosophy of the nineteenth-century reformer Henry George, apostle of the single tax. As editor of The Freeman in the 1930s, Chodorov delighted in attacking the economic prescriptions of Franklin Roosevelt and opposed U.S. involvement in World War II until Pearl Harbor.

Like his libertarian friend Albert Jay Nock, Chodorov regarded the state as the enemy. Though uncompromising in his beliefs, he was no ideologue. He respected “the integrity of personality and a mistrust of aggregated power.” His books and journalism in the decade after World War II influenced many younger conservatives like William F. Buckley Jr., who wrote for The Freeman in the pre–National Review days.

Chodorov took aim at one of the most powerful institutions in the country, the academy, believing that it was largely responsible for the shift from “individualism” to socialism. In 1950, most of the levers of higher education were in the hands of an informal but self-cognizant coalition of progressives, pragmatists, and socialists. Resisting them were a small congeries of private colleges, a handful of classical liberal academics, and conservative parents shocked at what their children were learning, and not learning, in class.

Writing in his newsletter analysis in 1950, Chodorov said that the collectivization of America had begun when progressive college students in the early twentieth century adopted the slogans of the socialists, impressed by their pretensions to “scientific exactitude.” They organized the Intercollegiate Socialist Society (ISS), which changed its name to the League for Industrial Democracy in 1921. ISS’s members included future leaders such as Clarence Darrow, John Reed, Walter Lippmann, Walter Reuther, Frances Perkins, Norman Thomas, and Stuart Chase. Speeches were made, pamphlets were distributed, conventions were held. The “success” of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia added impetus to the socialist crusade in America. At the head of college departments, Chodorov wrote, the socialists practiced their peculiar kind of “academic freedom,” scrupulously hiring their own kind.

When President Franklin Roosevelt looked for advice on how to deal with the Great Depression, he chose champions of the left who had established themselves through their books and articles. Businessmen were ignored because the socialists had convinced the public that businessmen “were at the bottom of all the trouble.” In his analysis essay, Chodorov argued that the only way to stop the descent into ever more statism was not by changing socialist laws through the political process but by inculcating the values that “make such laws impossible.”

Such a chore, he conceded, was difficult and lengthy; it would require perhaps as long as fifty years. It called for a “sincerity of purpose amounting to religious fervor.” It required the kind of zeal that had brought socialism to America and it ought to start, he said, where the socialists had begun—on the college campus. He titled his essay “For Our Children’s Children.”

It was a variation on a pamphlet he had written, “A Fifty-Year Project to Combat Socialism on the Campus.” Chrodorov proposed the creation of a network of campus clubs, a lecture bureau, and a publication “directed at the student mind.” He suggested the organization be called the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists (ISI). He shrugged off the non sequitur.

Chodorov believed that independent college students would respond favorably to a “radical” idea like individualism because he had given well-received talks at schools in New York City and at Yale. As a Yale undergraduate, Buckley remembered Chodorov’s manner as quiet, firm, “resolutely undemogogic.” The purpose of teaching individualism, Chodorov emphasized, was not “to make individualists but to . . . help them find themselves.” He knew how difficult it was to challenge a prevailing consensus. He wondered whether there was in America “a will for freedom of sufficient vigor” to support his idea.

He allowed himself some measured optimism when Human Events, the leading conservative newsletter of the time, reprinted his manifesto in September 1950. Letters poured in praising his proposal, although some parents argued that educating for liberty should begin earlier. Thousands of copies were distributed. The names of about one hundred students, suggested by parents and friends, were collected. Yet no organizational steps were taken because there was no seed money and no one to run the program. Chodorov thought someone young ought to lead the effort.

The idea simmered for over a year until March 1952, when Chodorov revisited it in another Human Events article headlined “The Adam Smith Clubs.” He argued that the clubs were needed “to find and help the submerged individualism on campus” and to provide an opposition “to the collectivism being ladeled out by the professors.” The reaction was not as dramatic as the response to the earlier essay had been, with one crucial difference—in the mail came a $1,000 check (equal to $10,000 today) from one of the most generous early benefactors of the conservative movement, the Sun Oil Company head J. Howard Pew.

Defense of the “American system of enterprise” was central to Pew’s philosophy. He said that “no economic planning authority could ever have foreseen, planned, plotted and organized the amazing spectacle of human progress that the world has witnessed in this country during the last one hundred years.” Chodorov’s proposal to start an organization of pro-freedom, anti-socialist college students inspired Pew.

Chodorov was uncertain how to respond to Pew’s largesse, however. Suggesting the formation of an intercollegiate society was one thing; building it was another. He put Pew’s check in a desk drawer and debated whether he should return it with his thanks. At last he showed the $1,000 gift to his boss, Frank Hanighen, the veteran journalist and editor who had built Human Events into an influential publication read widely on Capitol Hill. “I have one rule,” Hanighen said to Chodorov, “never send money back.” With Hanighen’s encouragement and after visiting Pew in his Philadelphia office, Chodorov formalized plans for the organization.

On April 3, 1952, the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists (ISI) was incorporated in the District of Columbia with Frank Hanighen, Frank Chodorov, and Patricia Lutz (Hanighen’s secretary) as the directors. William F. Buckley Jr. was listed as president, Frank Chodorov as vice president, and Aris Donohoe as secretary-treasurer. Buckley accepted Chodorov’s invitation to head ISI after being assured that the title was pro forma and his responsibilities would be strictly limited.

It would have been difficult for the young writer to say no: Chodorov had helped to edit Buckley’s best-selling book God and Man at Yale and recommended that Henry Regnery publish it. Chodorov himself had published Buckley’s first professional article in the spring of 1951 in Human Events, paying the usual $25. Buckley would publicly acknowledge Chodorov’s tutelage: “It is quite unlikely that I should have pursued a career as a writer but for the encouragement he gave me just after I graduated from Yale.”

ISI’s articles of incorporation reflected Chodorov’s libertarian philosophy, stating:

The particular business and objects of [ISI] shall be to promote among college students and the public generally, an understanding of and appreciation for the Constitution of the United States of America, the Bill of Rights, the limitations of the power of Government, the voluntary society, the free-market economy and the liberty of the individual.

Next, ISI had to test the market for a collegiate network committed to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. A questionnaire was sent to the original list of one hundred college students. Almost forty responded, saying they were either in “complete agreement” with ISI’s objectives or would like to receive ISI materials. They provided the names of several hundred other students who they thought might be interested. After dropping the 1952 graduates and adding the new names, ISI had a mailing list of six hundred undergraduates—out of a college population of 2.5 million.

Then Chodorov had to decide what materials should be sent to ISI members. Providentially, Leonard Liggio, a Georgetown University undergraduate, called on Chodorov in the late summer of 1952. A Catholic libertarian from the Bronx, Liggio had helped to form a group, Students for America, intended to carry on “the spirit of [Senator] Robert A. Taft and [General] Douglas MacArthur,” two of the most prominent conservative figures of the time. Liggio also visited Leonard Read, the head of the Foundation for Economic Freedom (FEE), and connected him with Chodorov. A deal was struck, and soon thereafter FEE began mailing its literature to ISI members free of charge. For Chodorov, this was manna from an individualist heaven. Missing from the mailings, however, were traditionalist conservative authors like Richard Weaver and Peter Viereck.

From ISI’s earliest days, those associated with the organization learned to expect the unexpected. In early 1953, Chodorov informed Bill Buckley (via Western Union) of a new lineup of ISI officers: “Am removing you as president. Making myself pres. Easier to raise money if a Jew is president. You can be V-P. Love. Frank.” Buckley, who had been a figurehead president and was deeply involved in starting up a new magazine, was relieved to be relieved. The demotion did not affect Buckley’s conviction that ISI was doing vital work for the cause of freedom.

On June 22, 1953, Chodorov filed a federal income tax exemption application “for use of religious, charitable, scientific, literary or educational organizations” with the Internal Revenue Service. While the organization had been incorporated a year earlier, that was only half of the work. The filing of a tax-exempt application meant that the society was now able to execute its business fully as a nonprofit corporation and to offer prospective donors federal tax exemptions for charitable gifts. As such, it is this date that ISI took to be its formal founding—from then forward charting its educational course “Since 1953.”

That fall, ISI hired its first and at the time only campus organizer: twenty-nine-year-old E. Victor Milione. Born in May 1924 in a Philadelphia suburb, at age seventeen Milione enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and wound up in Colorado. At the war’s end, he took advantage of the G.I. Bill and enrolled at St. Joseph’s College in Philadelphia, graduating in 1950 with a B.S. in political science. He went to work for Americans for the Competitive Enterprise System (ACES), an educational organization supported by Philadelphia businessmen. He traveled all over the greater Philadelphia area, visiting high schools and explaining the economic fundamentals of a free society.

While contemplating enrolling at Temple University’s law school, Milione began discussing with Chodorov (whom he had first met as a student at St. Joseph’s College) ISI’s project to change the intellectual climate on American campuses. Here was a worthy challenge for a young Catholic intellectual who believed that ideas were the wellspring of civilization. Undeterred by the fact that ISI had only $2,300 in its bank account, Milione signed on. Limiting himself to visiting schools in the East to save money, ISI’s intrepid representative provided students with “the arguments that support free-market economics, a respect for private property, and self-determination of the individual.”

Seeking to broaden ISI’s base, Milione proposed the creation of an advisory board. A skeptical Chodorov responded: “Aristotle and Spinoza are our board.” But he didn’t prohibit his young colleague from forming a board, whose first members were William F. Buckley Jr.; Brigadier General Bonner Fellers, USA (Ret.), a former aide to General Douglas MacArthur; Ivan Bierly, FEE executive secretary; Human Events editor Frank Hanighen; Utah Governor J. Bracken Lee; Hollywood actor Adolph Menjou; retired Admiral Ben Moreell, chairman of Jones and Laughlin; Professor William H. Peterson of New York University; John G. Pew, Jr., vice president of Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Company; Professor E. Merrill Root of Earlham College; and investment counselor Edwin S. Webster, Jr., of Kidder, Peabody & Co. It was an impressive lineup for an organization barely two years old.

Unwilling to depend on the publications of other organizations, ISI launched a newsletter, The Individualist, in May 1954. Reaction to The Individualist was favorable, with one notable exception: Russell Kirk declined the invitation to join the advisory board. He explained that he abhorred the word “individualist.” Politically, he said, individualism “ends in anarchy; spiritually, it is a hideous solitude.” He continued: “I do not even call myself an ‘individual’; I hope I am a person.”

Noting the consistently agnostic and libertarian character of the advisory board, Kirk suggested a markedly different pantheon of advisers:

Moses in place of Lao-tse, Aristotle in place of Zeno, Pascal in place of Spinoza, Falkland in place of Locke, Dante in place of Milton, [Samuel] Johnson in place of [Adam] Smith, Ruskin in place of Mill, Burke in place of Paine, Adams in place of Jefferson, [James Fitzjames] Stephen in place of Spencer, Hawthorne in place of Thoreau, Brownson in place of Emerson.

“I think,“ Kirk ended, “you people really are conservatives in your prejudices, not ‘individualists’; and you might as well confess it, and get the credit for it.”

Milione agreed with Kirk that the West faced a foundational crisis and that ISI ought to be concerned with all sides of man, not merely the economic. But he could not yet take the necessary steps to expand ISI’s mission.

Meanwhile, the ISI–FEE relationship became increasingly problematic. ISI membership grew so rapidly that FEE could no longer assume the cost of the monthly mailings. There were disagreements between Leonard Read, the strong-willed president of FEE, and the independently minded Milione. When Read tried to dictate what would be mailed to students and stated that all future funds would be raised under the aegis of FEE, not ISI, Milione decided it was time to move on. He rented space in a building near Independence Square in Philadelphia. It was only two small rooms, but the space was not shared with Human Events, FEE, or anyone else—ISI had declared its independence.

At the April 1956 trustees meeting, new bylaws were adopted and the “purposes” clause of the Articles of Incorporation was amended. Gone was any mention of “individualism.” With the new purposes clause, ISI ended its commitment to an individualism narrowly conceived and adopted a more humane understanding of man and society. No longer would there be a singular concern with homo economicus but a broad examination of what constitutes the whole man. Chodorov was re-elected president, but Milione was appointed executive vice president, preparing the way for his succession to the presidency.

The board meeting ended on a rising note of satisfaction about the thousands of students who were being exposed to the ideas of liberty; about the ambitious program of literature, lectures, and campus clubs for the coming school year; about the quiet determination and deep intelligence of the new executive vice president; about ISI’s location in Philadelphia, a place of political miracles as far back as the Declaration of Independence. Casting about for a fitting end to the meeting, a trustee quoted from Chodorov’s 1950 essay that had started the chain of events culminating in ISI: “What the socialists have done can be undone, if there is a will for it.”

Invariably describing itself as “conservative,” ISI reflected a new reality—an American conservative movement had come into being. The movement took its name from Kirk’s magisterial intellectual history The Conservative Mind, which examined conservative thinkers over a span of two centuries, from Edmund Burke and John Adams to T. S. Eliot and Winston Churchill.

One of ISI’s most important early publications was Richard Weaver’s 2,500-word essay “The Purpose of Education,” which was excerpted by the Wall Street Journal in October 1959. Weaver proceeded from the problem (education suffered from an “unprecedented amount of aimlessness and confusion”) to the cause (a failure “to think hard about the real province of education”) to the solution (a turn away from “life adjustment” theory to the disciplines that life requires). At the heart of those disciplines, Weaver argued, was language, “the supreme organon of the mind’s self-ordering growth.” Those who attacked the discipline of language were attacking “the basic instrumentality of the mind.”

Something called “social science” or “social studies,” wrote Weaver, was being substituted for history, and the student was being encouraged to give thought to the “dating patterns” of teenagers instead of the wisdom that explained the rise and fall of nations. One of the more pernicious claims made by the progressives, Weaver said, was that their kind of education fostered individualism. But true individualism was “a matter of the mind and the spirit”—it meant “the development of the person, not the well-adjusted automaton.”

What the progressives really desired, Weaver wrote, was to produce the “smooth” individual adapted to “some favorite scheme of collectivist living,” not the person of “strong convictions, of refined sensibility, and of deep personal feeling of direction in life.”

Weaver decried the educational breakdown brought about by the “collectivist political notions” of the progressives. He offered an alternative that required a discipline of the mind and the spirit that led to true freedom. Weaver was describing what we now call conservatism, although he did not use the word.

The center that had held in the late 1950s, wrote the historian James T. Patterson, cracked open in the 1960s because of a succession of cruel and mocking events. One president was assassinated, and another decided he did not dare run for reelection. The civil rights movement transformed the way America looked at its black citizens, but the leader of the movement was murdered in a Memphis motel. The most powerful nation in the world committed half a million men and $150 billion to defeating communism in Vietnam and was fought to a standstill by a small Third World nation. Millions had cheered John F. Kennedy when he declared: “we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty.” Eight years later, more than 600,000 people were participating in antiwar demonstrations in Washington, D.C. Eight million young people happily enrolled in the nation’s colleges and universities, which by the end of the decade were riven by anger, fear, violence, and death.

The right challenged the liberal establishment throughout the decade, capped by the presidential candidacy of Barry Goldwater. The 1960s were a heady time for conservatives who came to believe, swept up in the revolutionary spirit of the age, they could accomplish almost anything through politics. When Goldwater was buried under an electoral landslide, many conservatives despaired, but not Vic Milione.

Writing to the Notre Dame professor Gerhart Niemeyer, Milione argued that the election of a conservative as president would mean little “without an increase in the effort to restore the root values of our civilization in the intellectual center of American life.” He conceded that such a restoration was “a tremendous task” but not an impossible one, because, he said, quoting Tocqueville, “every fresh generation is a new people.” ISI would stick to its mission to educate for liberty. This was given concrete form by Milione’s philosophy, shaped by thinkers such as John Henry Newman, José Ortega y Gasset, and Richard Weaver.

From Newman, Milione learned that fragments of the truth are found in many disciplines so that an approach to the whole truth about man requires the student to confront a variety of perspectives. In an era of increasing specialization and professionalism, ISI insisted on the importance of traditional broad learning.

From Ortega, Milione learned that true education involves the cultivation of cultural norms, which are the preconditions of sound judgment. The norms represent the best insights of the past. Milione believed it was particularly important to remind the rising generation—hubristic in an age of scientific and technical “progress”—about the great achievements of the Western tradition. ISI distinguished between the truly profound truths and passing fads.

From Weaver, Milione learned a lesson that distinguished ISI from other educational organizations—students are not “objects” but individuals. They must not be used to achieve any political end but must be allowed to develop their own intellectual abilities and cultural interests. When students encountered ISI for the first time, they were surprised to find no ulterior motive behind its activities and literature. They were soon captivated by the idea of education as education and not an ideology.

Seventy years ago, Frank Chodorov had an incandescent idea about the need to educate the nation’s children and its children’s children about the free market and individual freedom. His idea became the charter of the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists (ISI). ISI, renamed the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, metamorphosed under Vic Milione and his successors, who recognized the spiritual as well as the material side of man. Today, ISI is one of the indispensables of the conservative movement. It continues preserving and extending liberty, knowing that such work is never finished because the road to liberty is never-ending.

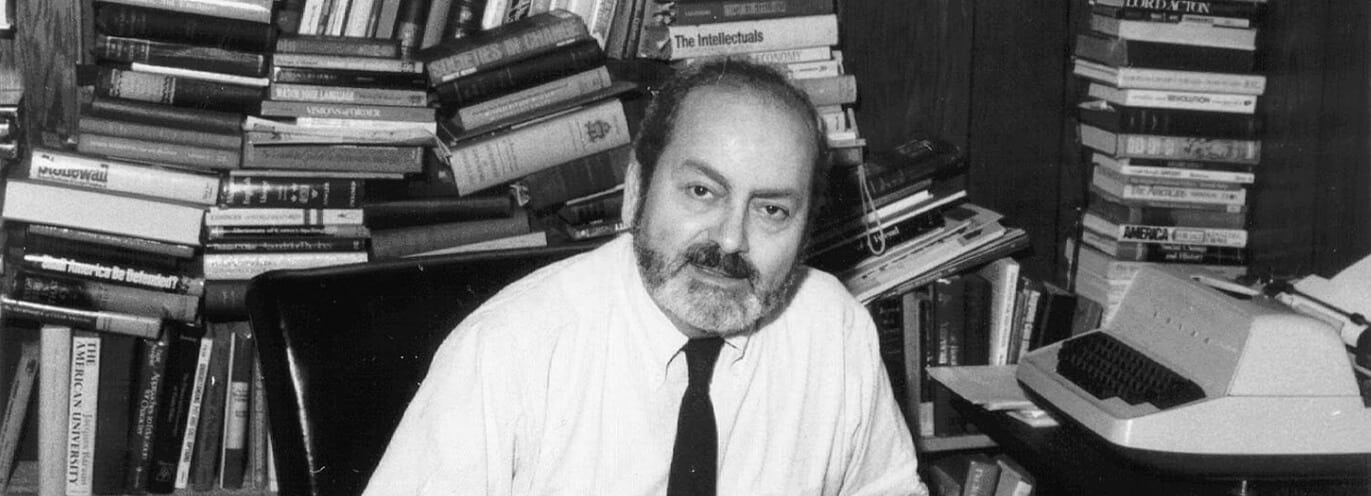

Lee Edwards is a leading historian of American conservatism and the author or editor of twenty-five books, including Educating for Liberty: The First Half-Century of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, from which this essay is adapted.