As I sat down to read R. Emmett Tyrrell, Jr.’s witty new memoir, How Do We Get Out of Here?, I remembered a story. Some years ago, I accompanied Tyrrell, or “Bob” as he is called by those who know him, to an Army–Navy football game out at what was then named FedEx Field in Landover, Maryland. It was a more innocent time, back when the NFL team that normally played there was still permitted to be called the Washington Redskins.

The temperatures were frigid. We were joined by the broadcaster and longtime American Spectator contributor Mark Hyman, who immediately observed that I was underdressed for the occasion. As a Bostonian, I adhere to strict standards as to when and under what circumstances I will wear a coat in the Washington, D.C., area. Tyrrell, a Chicagoan, fortunately had no such bizarre sartorial hang-ups.

What I was not quite so fastidious about was remembering where we had parked the car. I hasten to add that no one had drunk anything stronger than hot chocolate, which was purchased more for warmth than consumption. I merely held mine and might well have bathed in it if an appropriate location for doing so could have been found. After several hours in the cold air, we were doomed to wander the parking lots for what felt like forty years in search of our escape vehicle.

Luckily, though then approaching seventy, Tyrrell was in impeccable shape. His daily handball regimen easily surpassed my meager exercise routine. Tyrrell eventually led his young charge to safety, and I lived to tell the tale. Around this time, we were entering a period of unified Democratic control of the federal government that we at the American Spectator then called our “wilderness years.” Tyrrell was just as determined to lead us out of the wilderness as he was to figure out the answer to his question: how do we get out of here?

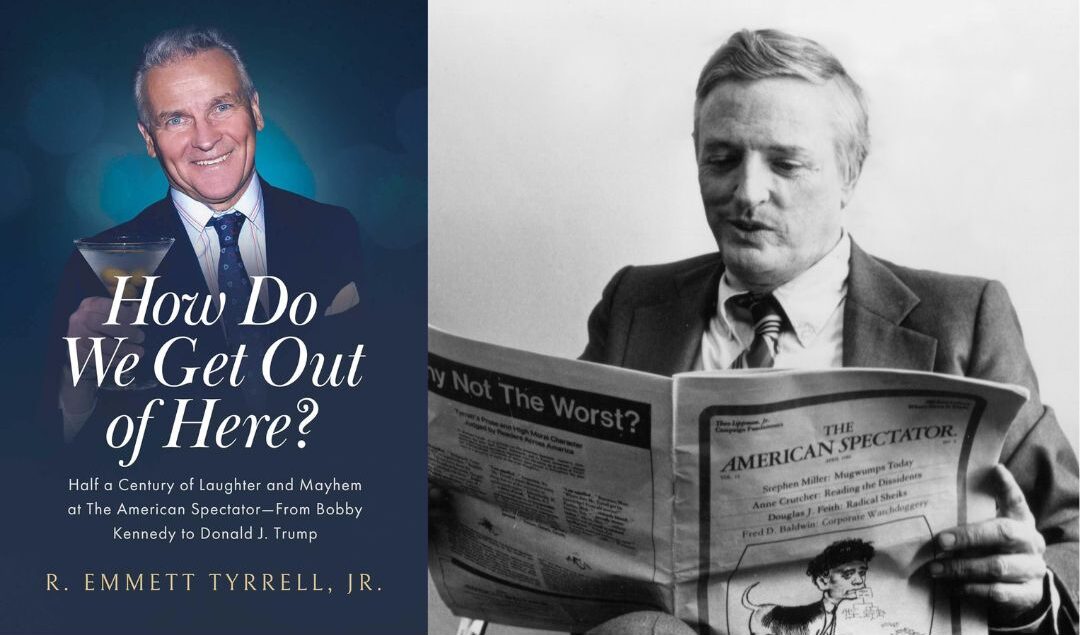

Tyrrell’s new book should nevertheless not be doomed to the same fate as Richard Weaver’s Ideas Have Consequences, remembered, not least by conservatives, as much for the title as its contents. How Do We Get Out of Here? is an interesting story that could double as a history of the modern American conservative movement, told with vigor and good humor.

It begins with Tyrrell as a young conservative upstart on the campus of Indiana University in 1968. Robert F. Kennedy was there in his quest to win the state’s Democratic presidential primary, speaking to a packed auditorium of students who rather than get clean for Gene preferred to get slobby for Bobby. Tyrrell, however, was the only one on stage with him, a “solitary figure standing behind the massive black curtains that were his backdrop.”

“All that was on my mind that day was how ironic it was that I, a stalwart of the New Right as it was then called, was within a few feet of the liberals’ great hope for a reiteration of Camelot or of the New Frontier, Bob Kennedy!” Tyrrell writes. But the then twenty-four-year-old was already committed, with a Reagan for President campaign button stored safely in his pocket, which he eventually gave to Kennedy.

Many conservative journalists get their start in college, emulating William F. Buckley Jr. and National Review. “Bill was the conservative movement’s guiding light,” Tyrrell writes. “Certainly, he was our guiding light.” Few, however, start publications during their college days that go on to become peers with Buckley’s magazine, as the Alternative, later renamed the American Spectator, did.

Tyrrell nevertheless acknowledges his debt to Buckley and other National Review luminaries, such as Bill Rusher, Frank Meyer, and Ernest van den Haag, calling them “essential for keeping us on a path that was a little less madcap.”

“They provided essays and reviews, but mostly they provided interviews,” he continues. Yet Tyrrell tried to repay these debts before they had been fully accrued. “In 1966, I had sent [Buckley] a check for $264,000 in answer to his yearly appeal to loyal readers of National Review,” he recalls. “At the time I had just $27 in the bank, but if Buckley said he needed $264,000 to cover his annual deficit, I was willing to write the check. Luckily, he was not willing to cash the check. For a certitude, it would have bounced, possibly into outer space.”

From its founding in 1967, the American Spectator always exemplified its founding editor’s joie de vivre and sense of fun. It was also generally less interested in setting conservative orthodoxy than was National Review. Members of Richard Nixon’s speechwriting team were early contributors. “Its link to us was John Coyne, a superb literary stylist and master craftsman of books, essays, and reviews,” Tyrrell writes. “He lined up writers from the president’s staff, such as John Avey (really Bill Gavin), Aram Bakshian, Ben Stein, and eventually in one capacity or another Pat Buchanan and Bill Safire, who soon moved on to the New York Times.”

George Will was an early national correspondent. Decades later, the by then more established Will asked not to be named in American Spectator advertisements, saying he had not written for the magazine in ten years. Tyrrell writes that he showed the veteran columnist a much more recent piece and quips that he never heard from Will again.

Tyrrell also says his magazine served “as a bridge on which the neoconservatives could cohabit peacefully with the conservatives. Bill Buckley and Irving Kristol became genuine friends in part because of their shared relationship as mentors to The Alternative.” He adds that the first neoconservative to regularly contribute was Daniel Patrick Moynihan, before undergoing the leftward “typical evolutionary process for members of the Democratic Party since the late 1960s.”

He laments a similar evolution among the children of neoconservative eminences who had never been avowed liberals before the presidency of Donald Trump. “In the 1990s, Bill Kristol and John Podhoretz were comfortable wearing their fathers’ colors of neoconservatism,” he writes. “In 2016, they were even more comfortable wearing the colors of the Never Trumpers.” He concludes of Kristol, “My friend of fifty years had now taken up with his lifelong enemies. His father would not be pleased.”

Tyrrell’s relationships with various presidents are an indispensable part of the story. A Cold War conservative, he remains a dutiful supporter of Ronald Reagan, whom he describes as “a man governed not by the ideology of a liberal but the disposition of a conservative” (emphasis in the original). But he is also an admirer of Richard Nixon and George H. W. Bush. Tyrrell had Reagan to dinner at his house and brought Taki Theodoracopulos to dine at Nixon’s home. Ever the party loyalist, he was even an ardent defender of George W. Bush during the depths of the Iraq War.

Perhaps more surprisingly, Tyrrell was an early adopter on Trump. One of Trump’s initial outings to make inroads in the conservative movement was a 2013 American Spectator dinner during which the future president accepted an award. “He was tremendously amusing. He was gracious,” Tyrrell writes. “He had an abundance of energy . . . He made a series of perceptive observations on public policy that turned out to form the foundation for his America First program. He even flirted with my wife.” Tyrrell notes approvingly that Trump stayed for the duration of the event.

Tyrrell recounts a major Trump speech on foreign policy: “Delivered by Donald from the Mayflower Hotel in Washington on April 27, 2016, it broke with President George W. Bush and neoconservatism on the question of nation building.” Tyrrell concludes that Trump “became the first president since President Eisenhower to resist sending American troops to fight in foreign wars. Once again, Donald was making good on a campaign promise.”

But it is a Democratic president with which Tyrrell and the American Spectator became most associated. Tyrrell recounts with relish his tormenting of Bill and Hillary Clinton (the latter he nicknamed “Bruno”) while maintaining that the journalistic record of his investigations compares favorably with Woodward and Bernstein’s pursuit of Nixon.

The magazine ascended to new heights in circulation and notoriety in the 1990s, but not without cost. Tyrrell mentions the “eerie moments” that followed stories detailing Arkansas state troopers’ facilitation of Clinton’s voracious sex life. “There were nights spent with hired bodyguards in the Arkansas countryside,” he writes. “Even worse, there were nights spent without bodyguards.”

Tyrrell is a survivor. He clearly takes great pride in the American Spectator outlasting the Weekly Standard, which in 2001 seemed rather unlikely, and his success in rebuffing several takeover attempts, including what he described as a “decidedly unfriendly” one by the Clinton Justice Department that “could have ended with my incarceration.” He briefly lost control of the magazine to George Gilder, who blurbs the book and gets off much easier than the others do.

The feuds are many, and sometimes hard to follow. (Some less so than others, such as his designation of the liberal turncoat David Brock as a “gifted writer, but hopeless coward.”) But also legion are the writers mentored by Tyrrell and his longtime No. 2, Wladyslaw Pleszczynski. That is a lasting legacy.

Tyrrell ends on an uncharacteristically solemn note, pondering God and perhaps his own mortality. Life is short, the now eighty-year-old scourge of the countercultural left acknowledges. But the crisis, as ever, continues.