There seems to lurk in the chests of Russia’s greatest musicians a westward—or even a specifically American—yearning. Take the composer Igor Stravinsky, for instance. Unable to return to Russia after the Russian Revolution of 1917, he moved around Europe and the United States and ended up in Los Angeles. The violinist Jascha Heifetz also migrated to California, where he set up a private teaching studio that attracted the best students from around the world. Sergei Prokofiev, another legendary Russian composer, headed to San Francisco at the start of the Russian Revolution and did not return to Russia until 1936. The piano virtuoso Daniil Trifonov appears to have done something similar. Trifonov did not leave Russia under the duress of political upheaval; he came to the Cleveland Institute of Music (CIM) to study with the great Sergei Babayan. But westward he nonetheless went, and he has now released an album of his favorite American musical influences.

Born in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, in 1991, Trifonov became a piano sensation while studying with Tatiana Zelikman at the Gnessin School of Music in Moscow. After medaling at three of the world’s most prestigious piano competitions, he pursued studies in both piano performance and composition at CIM (where he subsequently premiered his own piano concerto with the CIM Orchestra in 2014). Trifonov now tours the world as a piano soloist and chamber musician and has produced nearly twenty recorded albums.

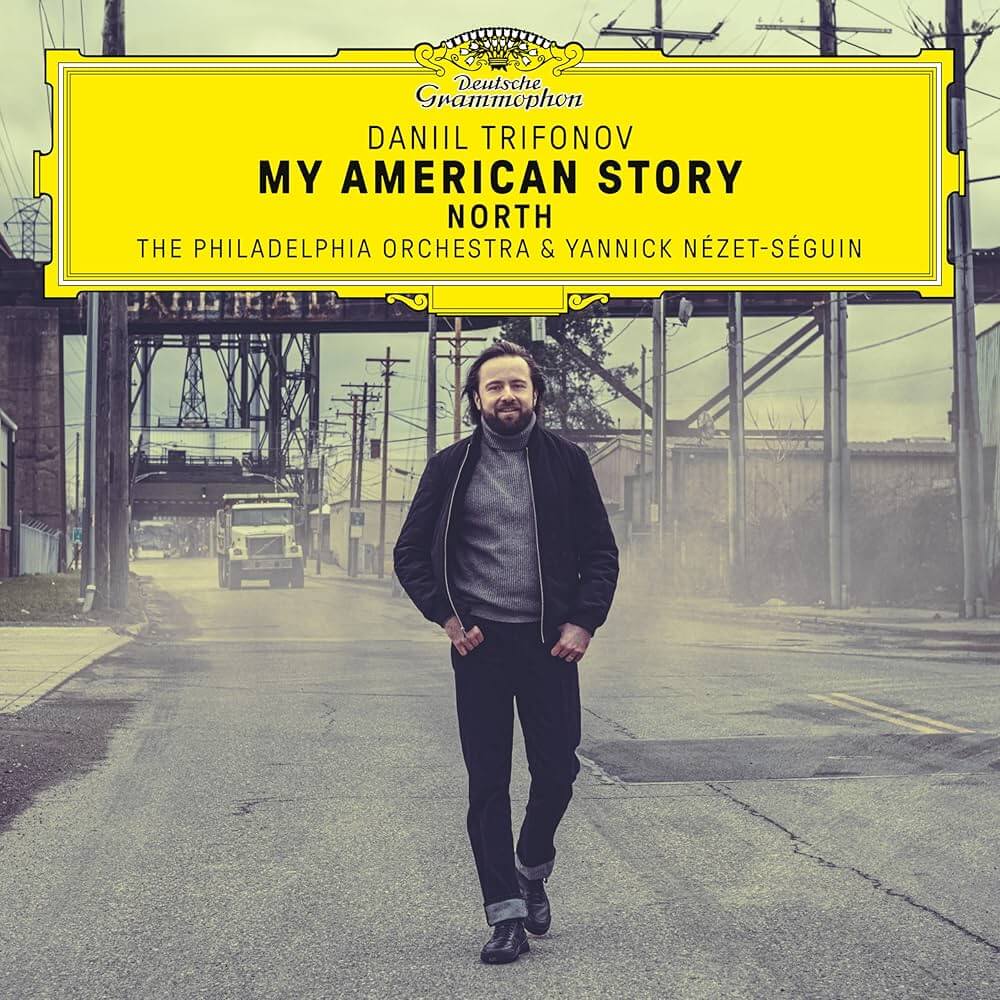

Trifonov’s latest offering is titled My American Story: North. Such a directionally specific title left me wondering whether Trifonov will circumnavigate his way around the compass and release three more albums that lean to the south, east, and west, respectively. Regardless, North is an impressive achievement. Trifonov applies his stupendous talent to jazz, swing, film music, serialism, minimalism, video game music, and Romantic-style concerti.

The album begins in earnest (after a brief but breathtaking Trifonov transcription of Art Tatum’s “I Cover the Waterfront”) with George Gershwin’s famous Concerto in F. For this performance, Trifonov is accompanied by the Philadelphia Orchestra and the conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Both Trifonov and the orchestra are at their best with the concerto, which rambles along with a perfect blend of bombastic eagerness and jazzy relaxation. Trifonov’s playing captures those most Gershwin-esque of influences—nostalgia and romance—so naturally that I came away with the impression that he could just as easily have become an internationally famous jazz pianist.

As great as the Gershwin is, the highlight of the album is another Trifonov jazz transcription: Bill Evans’s “When I Fall in Love.” If you listen to nothing else from the album, listen to this. It’s the kind of performance only a true virtuoso could give. It’s magical.

Not often do I say of a contemporary classical composition that we are fortunate to have heard it, but Mason Bates’s piano concerto is, I believe, such a piece. One could reasonably see the Bates concerto, which Trifonov places at the end of the album, as a microcosm of the musical tastes at play in North: jazz, film music, minimalism, romanticism, and so on. And the similarity of interests between the composer and the pianist—particularly their shared love of jazz music and film music—resonates in the score. The first movement in particular seems as if it could have been pulled straight from a 1950s film score and dropped onto Trifonov’s keyboard. The percussion is used heavily, but unlike many modern compositions, its presence is not overdone.

The album is not without blemish. There are two of them, in fact: Copland’s Piano Variations, a serialist composition written in 1930, and John Cage’s 4’33”, a minimalist composition written in 1952 in which the performer simply sits at the piano without playing any notes. I’m willing to forgive Trifonov for the Cage, if only because 4’33” is such a staggeringly (but famously) ridiculous composition that the fault for its appearance cannot be placed wholly on Trifonov’s shoulders. Sadly, its inclusion in the album achieves the same effect it always does: a sense of unending aimlessness, mixed with the urge to laugh at what one imagines must be a joke and the simultaneous fear that it is, in fact, not. For the Copland piece, however, Trifonov cannot be allowed to escape so easily. As I listened, I found myself wondering what Trifonov hears in the unintelligibility and clangor of Copland’s serialist experiment. Copland abandoned serialism soon after composing the Piano Variations and began writing the tonal and melodic music that, to this day, defines the American musical landscape. Leonard Bernstein once said that he used Copland’s Piano Variations at parties to “empty the room, guaranteed, in two minutes.” Had even Trifonov been the one playing it, I confess that I would have left the party too.

Thankfully, these unfortunate selections offer only a momentary distraction from the brilliance of the album. Trifonov is, well, Trifonov. And his presentation of the sounds of America is, on the whole, a delight. I look forward to following the next direction his musical compass points him.