The historian Brook Poston gives readers an interesting take on James Monroe’s political career. The fifth president of the United States was the first not to have been central to the Revolution and the consequent establishment of republican governments for the new American states and federal union, but his presidency seemed to many at the time to be a kind of culmination of the country’s republican Founding. Readers of The Founders’ Curse: James Monroe’s Struggle Against Political Parties will see how a protégé of Thomas Jefferson both could have participated in strongly partisan endeavors in the 1790s and worked energetically to prevent a recrudescence of party activity in the 1820s.

The text of this book is only 167 pages long, and over one-third of it goes by without Monroe’s engaging in “struggle against political parties.” In the first chapter, one sees Monroe serving a kind of apprenticeship under Jefferson, the figurehead of 1790s Republicanism, who tutored him in law and supported the younger man in his political endeavors. “Of all his many political connections,” readers are told, “Monroe’s friendship with Jefferson was the most important.” Poston calls Jefferson Monroe’s “mentor” in both law and politics, saying that “it is difficult to overstate the role Jefferson played in shaping Monroe’s political career” and that “the teacher-student nature of their relationship lasted until Jefferson’s death in 1826.” Monroe always conceded this point. Poston describes Monroe as “perhaps the most ardent” of the Republicans, which is a hard case to make. (How is one to weigh his ardor against that of, for example, John Randolph of Roanoke, Spencer Roane, John Taylor of Caroline, or Jefferson himself? All of those men were entirely unabashed too.) This is a point at which, since the book is from an academic press, historiographical references appear in the main text, not in the endnotes. Lay readers will likely find this format to be distracting through the rest of the book, and since Poston relies on classic works by Lance Banning, Noble E. Cunningham, Jr., and the like, along with Harry Ammon’s leading and Tim McGrath’s recent Monroe biographies and the new edition of Monroe’s papers, experts may find the sources to be obvious. Saving this material for the endnotes would have been preferable.

Poston’s account of Monroe’s early life and career is generally sound, though the reader may be perplexed by the assertion that “Monroe was nominally an antifederalist, but he never actively opposed the new constitution.” Monroe voted “nay” on ratification in the Virginia Ratification Convention of 1788, in which he was seen as ranking with the Anti-Federalist leaders Patrick Henry, George Mason, and William Grayson. Yes, his objections to the unamended Constitution were less far-reaching than theirs, but he did stand against James Madison for a Virginia seat in the first U.S. House of Representatives. If he had been merely a Federalist who was for amendments, he could have contented himself with Madison’s pledge to seek amendments.

Monroe was a close ally and top subordinate of Jefferson’s during the famously heated political battles of the 1790s. He became increasingly devoted to the American friendship with the French Republic and thus found himself to be suspicious of the motives of Federalist Francophobes such as Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. The latter had earlier irked Monroe during the Confederation by requesting a change in diplomatic instructions that would have allowed him to cede America’s access to the Mississippi River in exchange for trade access to Spanish colonial markets in the Caribbean, and Monroe’s suspicion of him would linger until the end of Jay’s life. In this political battle, Monroe made himself a kind of hero for Americans beyond the Appalachians, who could not have done without the Mississippi. Not for the last time, political benefit and political principle went together for Monroe.

Soon, Monroe found himself posted to Paris, where he made Francophile noises. As Poston writes, “Monroe’s posting eventually led to his locking horns with almost every major Federalist of the era, from Hamilton and Washington”—not precisely a Federalist, but close enough—“to John Jay and John Adams.” It was as a Jeffersonian that he quarreled with them, and his Jeffersonian hopefulness about the French Republic made them unhappy with him—to put no finer a point on it.

The book’s second chapter concerns the vehement struggle between the Republicans and Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist Party in the 1790s. Monroe sniffs out an intention for “a dismemberment” of the Union in John Jay’s behavior in particular, and, as Poston puts it, “came to view most differences of opinion as political intrigue from his opponents.” Like Jefferson and Madison, however, Monroe did cast many of his objections in constitutional terms. In general, Poston’s retelling of the tale of the 1790s is consistent with the reigning accounts (though at one point he mistakes Hamilton for a secretary of state).

Monroe ended up in Paris, where he seemed to Federalists and, ultimately, to President Washington to be too sympathetic with his hosts in the ongoing European wars. For his part, though Monroe thought that Jay’s Treaty was just as excessively pro-British as he had feared it would be, he labored to keep the United States in its allies’ good graces. Secretary of State Timothy Pickering recalled him anyway.

He returned to the United States just in time to find himself at the center of a controversy involving the only Federalist more important than Jay, Alexander Hamilton. It is hard to see how the Reynolds Affair could be blamed on Monroe or his Republican colleagues, but Hamilton certainly thought they might have violated their word as gentlemen. Pushed by Hamilton to concede that he had given his endorsement to documents that might be read as impugning Hamilton in relation to his behavior as treasury secretary, Monroe repeatedly insisted that he had no opinion on the matter. When Hamilton insisted that was insufficient to absolve him of official misbehavior, Monroe at last replied, “If your object is to render this affair a personal one between us you might have been more explicit”—in other words, if you intend to challenge me, do so. While that was not the case for Hamilton, Poston notes that “this was the only time on record when Monroe seriously considered a duel.” The matter ultimately petered out.

In Chapter 3, “The Antiparty Presidents: James Monroe and George Washington,” the book arrives at its subject. Like virtually all of his cohort of American politicians and the generation before him, Monroe deeply admired George Washington. His experience in the Continental Army likely gave him a particular appreciation of the commander-in-chief’s remarkable performance in the political aspect of the war and its aftermath. Despite their political falling-out over Monroe’s Francophile public behavior as minister to France in the 1790s, Poston says that “with Washington’s death in 1799, Monroe not only forgave his former commanding officer, but almost immediately renewed his worship of the man.”

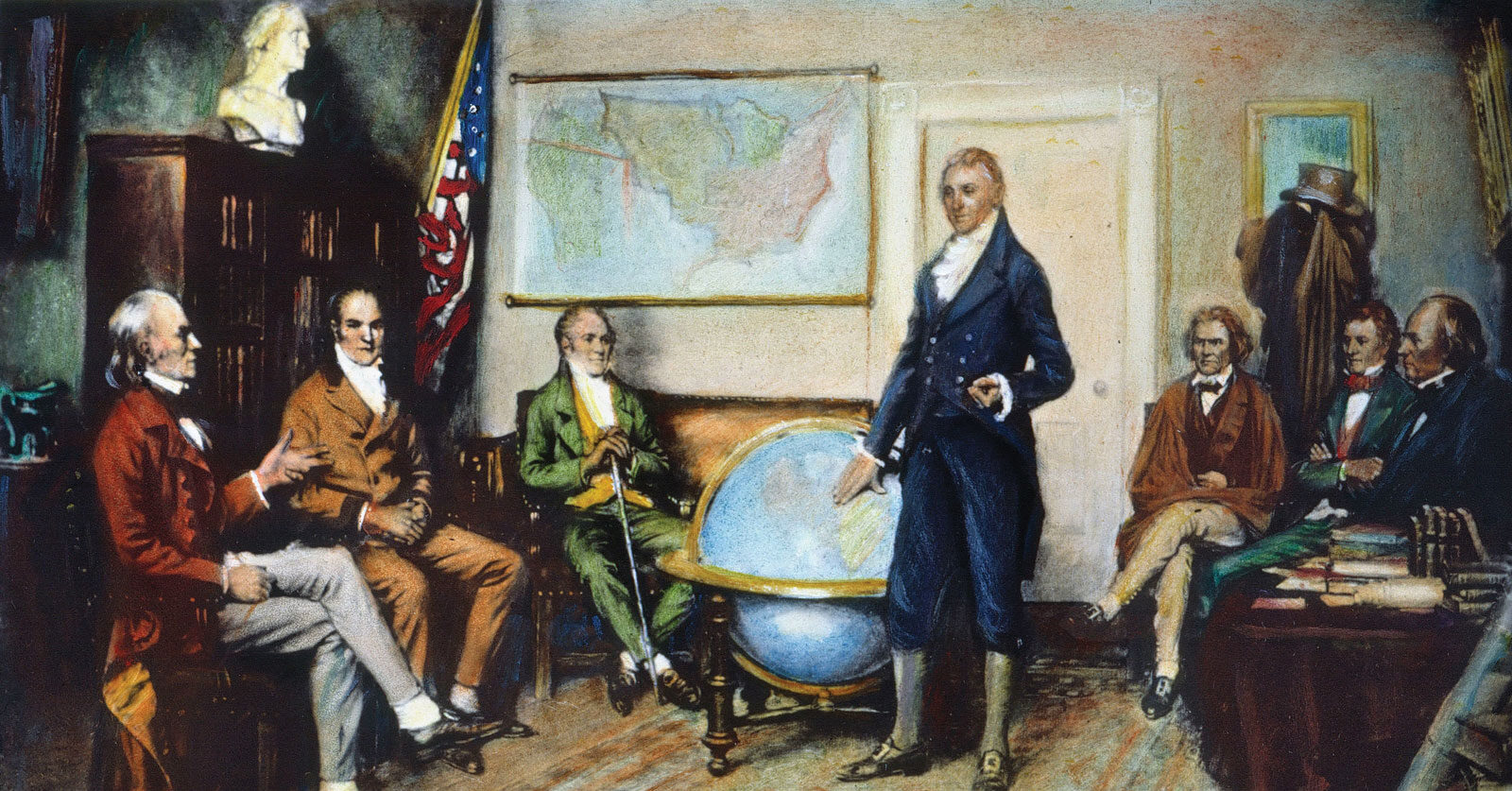

One manifestation of this “worship” was Monroe’s notable emulation of his presidential predecessor in undertaking three tours of the country. It was during one of those tours that a formerly Federalist Party–aligned newspaper in Boston said that the United States had entered into “an era of good feelings”—a nonpartisan epoch. Here was precisely the development Monroe hoped to bring about. If the Republicans maintained their principles while accepting the sincerity of prominent former Federalists who had seen the error of their ways, they could hope to bring common party members to see the light. Popular and elite response to Monroe’s tours seemed to him to show that his approach was working.

Given his hopes and observations, Monroe might be expected to have been perplexed by the Missouri Controversy—which mushroomed from an attempt by some Northern congressmen to exclude slavery from Missouri into a debate about slavery’s future in the entire American West. To the contrary, however, he had a ready explanation for this significant manifestation of sectionalism: Senator Rufus King of New York, a former Federalist, stood against his principles as John Jay and Alexander Hamilton had done. As Poston describes Monroe’s thought at the time, King was “the last major Federalist leader and, in Monroe’s mind, the prime mover behind the Missouri controversy,” and through manipulation of the crisis “Federalists planned to return to power.” This was a last-ditch effort “to use the Missouri question as a means to inflame antislavery sentiment in the North” and by doing so to steer northern voters into opposition to the new dispensation. (Poston even entitles this chapter “The Last Monarchist.”) That King had played a prominent role in early such conflicts, those not involving slavery, predisposed Monroe to read his behavior in 1819 this way.

Probably the most obviously anti-party step James Monroe ever took was his fateful appointment of John Quincy Adams to the office of secretary of state. One might have thought that a member of what John Randolph of Roanoke famously dubbed “the American House of Stuart” would be the very last person Monroe would put in the No. 2 slot in his administration, but this would be to ignore Monroe’s intention to write finis to the tale of federal party politics. That neither John Adams nor his son had been a partisan, exactly, made Monroe’s elevation of John Quincy a particularly apt gambit—even if he had not been so entirely fit for the post. The two of them worked superlatively well together. When Monroe stood for reelection in 1820, he received all but one Electoral College vote.

Poston’s account of Monroe’s career ends on the disappointing note of Martin Van Buren’s, John Calhoun’s, and Thomas Ritchie’s use of Andrew Jackson’s image to undo Monroe’s great achievement of nearly ending party conflict. Van Buren’s dismissal of anti-party policy as “the Monroe Heresy” captures the following decades’ attitude nicely. Poston thinks the almost immediate disappearance of nonpartisanship from the highest political circles owed much to Andrew Jackson’s personality, but although Jackson was indeed insistent that people were either for him or against him, one can wonder whether James Madison, writing as Publius, was not right in insisting that in complex societies party is more or less inevitable. “Faction Jackson” (as Poston entitles his final chapter) was, after all, a vehicle for Van Buren, Calhoun, and Ritchie, not the Democratic Party’s chief organizer.