We are the first of mankind to see and sense the Earth as a small place. I can now hang upon my wall, just as easily as a picture of my own house, a photograph of our terrestrial ball taken from outer space. But the essential reason for our new assessment of our planet is our recent ability to move to almost any point of the sphere within a day or two. Distances have been contracted by a miraculous increase in our speed of displacement. It is a common saying that thought is quicker than action: this holds true in the case of imagination, not so in the case of more reflective use of the intellect. Our popular fiction now, boldly over-stepping our powers, sets its adventures in “The Galaxy”; in the meantime, however, our approach to our here-and-now problems is still weighted down by our age-old habits of slow movement. Our views lag far behind the change in our circumstances: this change deserves to be stressed.

The Revolution of Speed

For many centuries, the fastest means of land transport was the horse. Given roads or tracks, a horseman can cover seventy-five miles in a day; across country, the cavalry of Alexander the Great is said to have covered the same distance in thirty-six hours: two thousand years later this was still accounted a remarkable performance. Cruising speeds maintained over a long journey were of course a good deal lower: an average of forty-five miles was very fair. Horse-drawn wagons, when loaded, could under the most favorable circumstances equal the achievement of a walker. Thus, during the long-lasting Age of the Horse, there was a low “ceiling” on the speed of human displacement. This can be illustrated by an anecdote involving that exceptionally dynamic figure, Napoleon. In September 1805, he proposed to “fall upon the Austrians like a bolt,” and for that purpose he transported himself in his specially equipped car from St. Cloud to Strasbourg in three days: this amounts to one hundred fifty miles a day, and involved the frequent change of the best horses available to the Emperor.

Not only was the horse slow, according to our modern reckoning, but moreover the diffusion of its employment was slow. The horse was domesticated more than five thousand years ago in the great plains of Central Asia. But within classical Greece it was a scarce asset and its ownership a badge of class; the same situation obtained in the Roman Empire and in feudal Europe, which was all but overwhelmed on several occasions by an avalanche of Asiatic horsemen. Even though our children associate “Red Indians” with horses, we know that horses were introduced on the American continent only by Cortés, who owed his conquest of Mexico in no small part to the impression made upon the Aztecs by this hitherto unknown animal.

Turning our attention to sea transport, we find that the transatlantic clippers, soon after the Napoleonic wars, held an average cruising speed of over one hundred fifty nautical miles per day on their westward journey, a performance which was halved on the eastward passage. Strangely enough, a Viking ship is said to have done as well a thousand years earlier, crossing from Norway to Iceland in four days and nights at an average of one hundred fifty sea miles per day—or so a saga bids us believe. We have more solid authority, that of Thucydides and Xenophon, for the achievements of Athenian triremes twenty-five centuries ago: we are told of one such ship covering one hundred sixty miles in twenty-four hours, and of another covering six hundred twenty miles in four and a half days—of course impelled by a combination of sail and oar. It seems then that the great gain in navigation which had been achieved over the years was not mainly one of speed: it was an enormous improvement in seaworthiness and manageability, the major step of which was made in the construction of the Portuguese caravels in the fifteenth century, thanks to which Columbus reached the New World.

It is indeed fascinating to think that an improvement in the design of the sailing ship, and mainly of its rudder, allowed the hub of the modern world to be transferred from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic: it would surely be wrong to say that this technical factor was the cause of the event, but it was its precondition. And if an alteration of means, relatively so small, has been followed by so major an alteration of circumstances, what can we not expect to follow now that man has made a prodigious break through the long-lasting ceiling on his speed?

The gain in speed achieved over the Age of the Horse ranges from ten to one in the case of the motorcar to as much as a hundred to one in the case of the jet airplane. The change seems even more sensational when we associate with the increase of speeds the increase of weights which can be moved. By far the most striking progress of human technique is that which affects transportation of persons and goods. The economic benefits derived therefrom are too well known to need any stressing. Instead, I should like to draw attention to some of the political consequences.

Political Consequences of Speed

Let us compare the desks of Augustus, Jefferson, and Eisenhower. To all three desks come news “from all over the world.” There is a great difference between the desk of Jefferson and that of Augustus; since a far smaller fraction of the world was known to the Roman Emperor than to the American President, news came in from fewer points, and the geographic coverage of information was very much narrower. But there is a no less important difference between the desk of Jefferson and that of Eisenhower. News reaching Jefferson were affected with time lags which distance and difficulty of communication often made considerable. Therefore, the picture of the world pieced together by Jefferson from all items of information was a picture made up of non-simultaneous events and situations, even as is the case today with our picture of the heavens. Many “facts” he took into account had ceased to be “facts” by the time they had become “information” available to him. It is otherwise with Eisenhower: in his overall picture of the world there are no outdated elements; all the “facts” of which he is informed are “live facts,” facts in being.

It is a novelty that information should be instantaneous. But it is an even more important novelty that action at a distance should be near-instantaneous. The “Berlin air-lift” in 1948 was a striking demonstration in this respect, intervention in Korea another; the French air-lift to Madagascar offers a recent illustration: a century and a half ago, relief would have reached the island at best four months after the disaster, whereas in this case the delay was only three days.

Any increase in man’s power involves greater possibilities not only for good but also for harm: while it is unhealthy to concentrate upon the latter, it is unwise to ignore them. In past ages mere distance afforded a protective cushion to local autonomy and national security. Slow and costly communications opposed a physical obstacle to the centralization of decisions in a country’s capital. As all incoming information had to be borne by messengers, and all outgoing orders to be conveyed in the same manner, no central government could bear the costs involved in keeping sufficiently informed about local conditions to make decisions concerning them. Further, in the case of any rapidly changing local situation, the time-lag between composing a report and receiving the corresponding instructions was apt to stultify the latter. Therefore, it was in the very nature of things for local problems to be coped with by local authorities. And even if local dispositions ran counter to the will of the central government, it was such a complex and lengthy operation to bring agents of enforcement to bear that it was practical to let the local people settle their own affairs except in extreme cases. When such physical circumstances are kept in mind, it becomes clear that the opportunities for far-reaching dictation were insignificant compared to what they are today. Political despotism as we know it is a novel phenomenon. Not only were the kings of Western European States quite bereft of formal despotic authority; even the tsars and sultans and other Asiatic rulers, to whom despotic authority did belong, lacked the means to exercise this despotism throughout their vast empires.

It was an old Asiatic tag that if you wished to be safe from the will of the ruler you should stay away from his Court: but now this is not enough; the ruler’s eye and hand are everywhere. In the same manner it was an old European tag that if you wished to be safe from a surprise inroad of foreigners you had to stay away from the seashore. This latter idea dates back to the snatch raids of the Vikings. Sea-power was always the power to surprise. But even in the heyday of England’s mastery of the seas, the sharpest blows which England could deal at an enemy without warning were to pounce upon its merchant ships on the high seas and to bombard its naval forces in port. The more vital threat of invasion was one of which the intended victim inevitably obtained ample warning. It took a great deal of time to assemble infantry forces, which lumbered forward at a slow pace. It followed that the threatened nation was always at leisure to muster its own forces. Although it could be swamped by a great superiority of forces, it could not be struck down by surprise.

I clearly remember the discussions on the prevention of aggression which were initiated at the League of Nations thirty-five years ago; we then worked on timetables involving two assumptions. One was that quite some time would elapse during which the preparations of the aggressor would make his intentions manifest, and that this afforded a period for diplomatic intervention by the Council. The second assumption was that if the aggressor did indeed strike, the actual progress of his operations would be sluggish enough to allow the rescue of his victim by means of a long-drawn procedure comprising three stages: the formal decision by the Council to call upon member States, the mustering of forces by these States, and their combination on the field. It was stoutly maintained by British and Scandinavian representatives that the prior availability of some forces of intervention was unnecessary. All this implied a leisureliness which now seems quaint. Such procedures are clearly inadequate to the danger of a mission period during which visible preparasile attack, where there is no pre-aggressions invite diplomatic action, and no post-aggression period during which the victim is still unharmed enough to be rescued by hastily joined international forces.

Thus, we find that our gains in speed place the subject more in the hand of the ruler, and the nation more at the mercy of a foreign power than was the case until our time. This conclusion can be used to depress us or to fortify our spirit. It can fortify our spirit if we perceive these chances for evil as a challenge to mankind. By our own material achievement, we are driven so to educate ourselves that we shall forbear from harmful uses of our powers.

Social Consequences of Speed

The population of the Earth has increased more since the beginning of our century than it had done in the preceding two hundred fifty years. Furthermore, the rate of growth is increasing: two hundred years ago it required a good one hundred fifty years for the doubling of the population: by a century ago, this duplication period had fallen to about one hundred ten years; on the basis of current trends, which may of course change, the duplicating period has shrunk to forty years. Demographers worry over this and foresee an overcrowded planet, but any difficulty due to mere numbers stands a long way in the future and can be coped with in ample time. Speed, however, is a much more effective and immediate cause of overcrowding. A simple comparison will show how this is so.

We all know that if we heat a gas, it seems to demand more space, and if we deny it that space it bursts the receptacle in which it was formerly held without difficulty. Chemists tells us that heating is nothing but speeding up the movements of the atoms composing the gas so that each travels faster and collides more frequently and violently with others: here we find overcrowding arising from speed, not numbers. We enjoy over atoms the fortunate superiority of being able to control our movements (and that of our vehicles) in order to avoid collisions; but to do this we must submit to traffic regulations, which extend downwards even to pedestrians. The importance of traffic problems, and the status of traffic authorities, is sure to rise beyond present recognition.

We have compared our gains in speed to what occurs as the result of heating; and indeed, the comparison is justified, since heating is an input of energy, and we do increase, continuously and sharply, the input of energy into transportation, some of this energy going into the increase of the weights carried and a greater proportion into the increase of speeds. The comparison with heating can be used also to stress the point that speed, like heating, facilitates the mixing and combining of various substances. Difficulties of transport have in the past held back geographic movements of populations. In the nineteenth century the westward trek of the Americans and the northward trek of the Boers were regarded as epic, although in terms of “logistics” there was little difference between these migrations and the southward treks of the Germanic tribes which overran the Roman Empire, and historians have made it clear that these invaders were not at all numerous. Now, however, vast movements of populations are physically feasible. As a consequence, we must expect that the uneven distribution of world population over the surface of the planet will become an issue.

Reducing inequalities within the nation was the great theme of the last few generations in the various countries of the West, since people naturally compared their condition only with that of their neighbors. But we have invited the other nations of the world to take cognizance of our living standards. And while at present they are concerned to rival these standards on their own ground, should this hope prove fallacious (in part because of the unequal distribution of natural resources), the pressure to immigrate to countries which have achieved great success will be renewed, and it will pose moral and political problems.

One World

Two thousand years ago, enlightened Romans were wont to repeat a saying learnt from their Greek tutors: “Though mankind lies dispersed in many cities, yet it forms but one great City.” This saying has become imbedded in Western education through Cicero, who repeatedly referred to the Society of Mankind. Thus, when Wendell Willkie spoke of “One World,” it seemed that the statesman was at last acknowledging what philosophers had stressed for a long time. But the world today is “One” in a sense quite opposite to that which the Greek Stoics had in mind. The purpose of their saying was to contrast physical distance with moral proximity: moral nature made it as easy for men to get on together as physical nature made it difficult for them to come together. Now the situation with which we are faced is utterly different: it is one of physical proximity and moral distance.

Progress in transport has flung down the walls of distance which insulated the many human communities; but men have not rushed over these toppled walls to greet each other as long-lost brothers now enabled to merge in one great community. In North America and Australia the advent of Western man has led to the near-extinction of the natives rather than to their combining with the newcomers in one society. The prolonged presence of Western man in Arab, African, and Asian countries has quickened a feeling of kinship, not with him but against him. Clearly nationalism is the great political force in our age of No-Distance. Nationalism made Hitler, and unmade him when he ran foul of Russian nationalism, which alone saved Stalin’s regime. Nor is the will to nationhood dependent upon actual oppression: men now define oppression as the denial of recognition as a separate and distinct sovereign community.

There seems to be no basis in fact for the idea that men are naturally prone to treat each other as brethren and have been artificially weaned by institutions from this original propensity. The only evidence which can be adduced in favor of this natural brotherhood is that all men seem to have a deep-seated reluctance to kill another man, a reluctance which is overcome only under the stress of fear or extreme excitement: hence the war dances required to put them in that unnatural mood. But “not-killing” and “regarding as a brother” are very different attitudes, the second far richer in content. And the second is developed by institutions. It is quite impossible for us to estimate the number of distinct political communities which have arisen on our planet since the appearance of man. All but an infinitesimal fraction of these have disappeared; and, for want of any other means of picturing them, we pay a great deal of attention to the minute communities which have subsisted long enough to allow our anthropologists to examine them.

The feature common to all of these communities is an intense but narrowly restricted sense of fellowship. This makes us aware that the building of political societies which have mattered in history involved an enlargement, coupled with a weakening, of the sense of fellowship: our bond with a compatriot is nothing like the bond between members of a tribe; still it is a bond. And we may then think of the art of building large societies as the art of stretching bonds of fellowship as far as possible without snapping. The diffusion of a religion, of a language, of a legal system is here of far greater importance than the diffusion of tools and skills, though the importance of the latter is not negligible.

It would be mere wishful thinking, than which there is nothing more dangerous in the management of human affairs, to assert that mankind now forms One Great Society. This poses a problem because, and only because, mankind must increasingly be thought of as gathered in One Place. While it is certainly an obstacle to the achievement of human excellence that a society should be too small, it is far from clear that such excellence is fostered by increasing bigness. Greek society which has afforded us models in arts and philosophy was small: a constellation of towns of which the largest did not count a hundred thousand inhabitants. Even smaller was Jewish society, wherein was kindled the Light of this World. It is readily believable that the advocacy of the all-embracing society by the late Greek philosophers was in no small measure a means of consoling themselves for their absorption in the vast Roman Empire, which never got near to the achievement of Athens alone.

But if it can be doubted that the hugeness of society is desirable, there is little doubt that the mixing together of distinct societies retaining their distinctive traits is a cause of trouble: it was long illustrated in the Ottoman Empire. Contrary to the dreams of those who see in World Government a cure-all, experience proves that the unity of government by no means solves the problems raised by the distinctiveness of the communities over which it presides. Incidentally, in that event, the nature of things forbids that government should he of a representative character: if men attempted to make it such, it would be at worst representative of the dominant society and at best representative of the coalition of certain component societies against others. Representative government assumes that what is to be represented is a dominant opinion or feeling within one society.

Tensions between societies are not amenable to the remedy of a common government, unless it be a very authoritarian one. But on the other hand, when societies have distinct political existence, their conflicts are far more disastrous than those which occur between different States belonging to one and the same society. Burke explained the mildness of eighteenth-century wars in Europe by the fact that the nations involved belonged to same system of manners and could therefore contend only about some specific interest, which was not worth any great fury or havoc. It takes great folly to drive war to the extreme under such circumstances, and history offers but two such examples, the Peloponnesian War and the War of 1914. On the contrary war between societies is by nature absolute since it is not a squabble occurring within the same frame of values, but rather one in which neither camp recognizes the values of the other: this is potentially a war of destruction. Such were the wars waged by the Mongols and the Turks against Europe—wars between societies.

At present the combination of strong diversity between societies and of effective physical proximity poses a political problem of major dimensions. It is just not good enough to think of it in terms borrowed from the experience of diplomacy between States belonging to the same society.

Our Home

Underlying this paper is a feeling which it is perhaps time to express, an affection for the Earth similar in kind to that which our home and garden inspire, an awareness that our inheritance is precious and vulnerable. In most pre-Christian religions figured a cult of Mother-Earth, the Bountiful. She was the primeval giantess on which short-lived men scrabbled punily; from her flanks sprang all things necessary to the sustenance and enjoyment of life; her power was adored. The Earth is still our abode and provider, but the giantess now seems far smaller, and the majestic processes of her life are not immune to interference. We know that we live upon a few feet of soil, with a few miles of atmosphere above us; we know that we can blight the soil and corrupt the air, that we can produce smog and dust-bowls; we could poison the sea; we could melt the ice-caps at the poles; we might kill off bacteria on which we depend, or propagate viruses mortal to us.

Therefore, the juvenile pride which we have understandably taken in our fantastically increased ability to “exploit the Earth” should now give way to a more mature thoughtfulness in “husbanding the Earth.” Man, impatient with the weakness of his hands, has transformed his weakness to strength: now his handling must become more discriminating and delicate. We are like children who, as they acquire vigor, must become aware of their new capacity to injure. Many of us no doubt have had the experience of nursing with love in our maturity a small garden through which we had blundered brutally as small children, then deeming its riches unlimited: such is the experience which mankind is now repeating.

Now that we have reached the limits of the Earth, we understand: this is the land of promise, the land beyond Jordan, a land of milk and honey, to be enjoyed, and cherished, and tended.

The Capacity to Harm

I have traveled enough not to fall into the easy accusation that modern industry is responsible for defacing the Earth. I know that shepherds, so favored by poets, can with their lambs and sheep cause the soil to become barren; I know that noble savages will burn down a forest to raise a crop, and move on to cause another desolation; I have seen the squalor of the Arab medina and of the Asiatic large town. Man is careless; and if our factories pour filth into our rivers, this is just in line with age-old behavior. Yet the combination of education and wealth always fosters in men the will to live in graceful surroundings, and if this is an attitude of individuals it may also be an attitude of communities. It was the attitude of Athenians, of Florentines. Surely, if they were wealthy enough to build themselves beautiful towns, so are we. The preoccupation with urban beauty seems to me to be rising in the United States; I find it to a lesser degree in Europe. Also it is an attitude of mature minds to be provident, to think of improving the home, the farm, or the plant. Certainly we cannot blame our contemporaries for any lack of investment-consciousness, but this preoccupation has not yet, or at least not adequately, extended to the conservation of the very basis upon which our structures are reared: we do not realize that the natural requiring upkeep. This basic capital of mankind is entered in our account books at zero, and so taken for granted that it receives no attention.

The time has come for a new spirit of “stewardship of the Earth.” Every animal, however humble, provides for its offspring. As one ascends the chain of beings up to man, the period during which the young are protected by the parents stretches, allowing for more complete development. But man is unique is his determination to hand down to his adult successor some asset he has built up, to be enjoyed and improved by his son, and handed to the grandson for further improvement. As this propensity is peculiar to man and has obviously served the progress of our species, I doubt whether the legislative fashion against it, however plausible on other grounds, is well founded. But we must at least transfer this fortunate propensity to the asset on which the children and grandchildren of all of us shall be dependent, our Earth itself.

In towns where we have no animal company other than that of an occasional cat or dog, and see no plant other than an occasional tree, we are apt to forget that Life, with a capital L, depends upon a complex combination of an immense variety of forms of life, between which the balance must be maintained. We may have air-conditioning, but should be aware that the availability of breathable air depends upon a complex cycle of operations turning upon green plants. All our devised processes in which we take justifiable pride are, as it were, derivations installed on natural circuits; and our increasing understanding of the latter not only conveys a greater power to exploit them but also implies a greater awareness of a duty to preserve them.

Cleverness and Thoughtfulness

Throughout the history of mankind, as we know it today, new procedures have been devised, new tools forged, and new ways of life have been adopted. It is a truism that the pace of such change has undergone a formidable acceleration: but truisms are the best starting points for meditation. When a new procedure or new tool arose in the distant past, its use was only slowly generalized in the immediate environment and its geographic diffusion was even much slower. Inventions, far between in time and spreading sluggishly, slowly affected ways of life but did not revolutionize them: for instance, I deem it quite misleading to refer to the adoption of tilling as “the Agricultural Revolution”—a phrase which implies a turbulence of events which was lacking.

For many thousands of years men lived in a world where new practices were a rarity and old practices made up the bulk of their existence. While the impact of successive new practices successively altered the environment, this alteration was so leisurely that sons were, on the whole, adjusted to their world if only they acquired the skills of their fathers and were guided by the experience of their elders. But now discoveries so press upon one another, are so rapidly accepted and so widely put into operation, that a human generation lives in a world utterly different from that into which it was born; for instance, I was born in the year when the Wright brothers first succeeded in flying a few hundred yards, and flying has become my normal mode of transporting myself to and fro.

I marvel at the rapidity of human adjustment. Man, living in a sort of symbiosis with an ever-changing population of machines, reveals a flexibility of behavior which could hardly have been forecast. Moreover, while great individual inequalities are revealed in this capacity as in every other, they bear little apparent relation to hereditary background: given favorable early opportunities, the knack of handling complex machinery can be acquired quite rapidly by men born in the most primitive conditions. We are only beginning to discover man’s cleverness.

It is again a truism to say that our thoughtfulness by no means keeps pace with this development. Prudence consists in picking out the good under the actual circumstances: faults against prudence are committed either if one fails to take full cognizance of the circumstances or if one despairs of picking out the good: such indeed are the two trends of contemporary thinking about our fast-changing world.

Certainly, the stress upon our minds arising from the pace of change is unprecedented: no man in his right senses can help feeling that he is unequal to the challenge. Yet we must humbly dare to meet it.

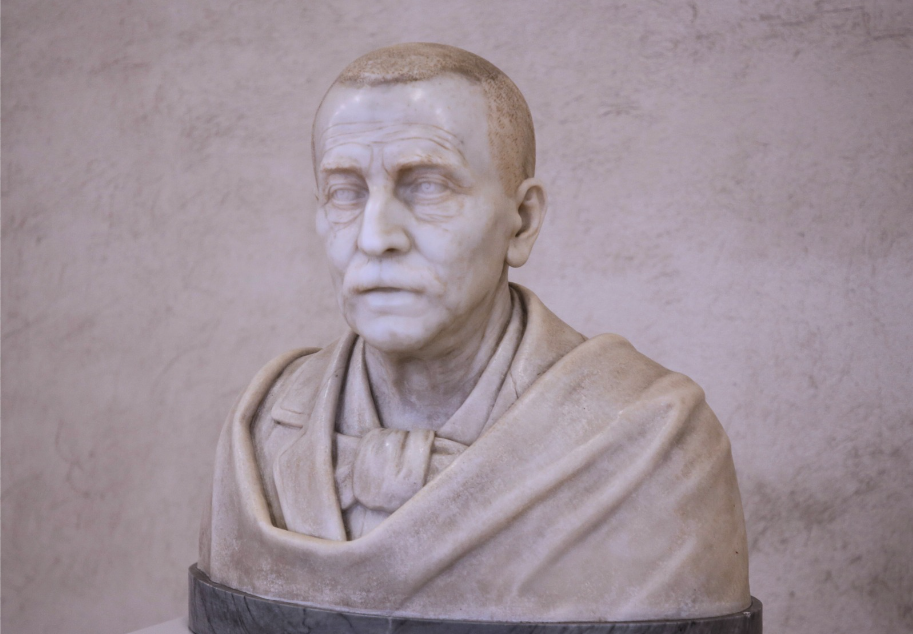

Betrand de Jouvenel was a French philosopher who wrote on topics specializing in the social sciences.