If I wish to spend time in the company of Flannery O’Connor, I might pick up her novel Wise Blood or turn to any random page in one of the volumes of her correspondence, especially The Habit of Being. I might listen to the recording of her strikingly inflected reading of her short story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” or burrow into the journal she maintained in her youth, published as A Prayer Journal.

More often than not, though, when I find myself wanting to renew my acquaintance with this great American writer, I sit down with her short story “A Temple of the Holy Ghost.” At the heart of the story are the sentiments of a nameless twelve-year-old girl who, in the credible opinion of O’Connor’s biographer Brad Gooch, was “an obvious stand-in” for the author herself. The child, as she is identified throughout the story, is precociously contemptuous of a pair of loud, catty, and boy-crazy older girl cousins who speak with irreverence about the third person of the Trinity: instructed by a nun to maintain their virtue by thinking of themselves as “a Temple of the Holy Ghost,” the cousins have taken to referring to each other, jokingly, as “Temple One” and “Temple Two.”

One can easily imagine young Mary Flannery O’Connor—who was born into the Catholic Church as surely as she was born in the Deep South—sharing her young protagonist’s abhorrence at her cousins’ mocking attitude. In contrast to her flighty, flippant cousins, the child loves the idea that she and all people house God within them: “I am a Temple of the Holy Ghost, she said to herself, and was pleased with the phrase,” O’Connor writes. “It made her feel as if somebody had given her a present.” The rest of the story illustrates the richness of that present and shows the demands it places on the recipient. Later on, in the sort of detail that cemented O’Connor’s reputation as a master of the Southern Gothic, the child hears of a hermaphrodite in a carnival sideshow who cautions onlookers against feelings of superiority: “God made me thisaway and if you laugh He may strike you the same way.” Then, in the final act, the child renounces her prideful piety in favor of something close to genuine repentance. At a chapel, she prays to become less mean and to speak with less sass. Then, her eyes fixed on the Eucharist, her mind turns to that hermaphrodite. “The freak was saying, ‘I don’t dispute hit. This is the way He wanted me to be.’” Here, O’Connor is writing frankly, candidly, and, I suspect, autobiographically.

O’Connor (1925–1964) did not always write so personally, but, to a striking and rare degree, her fictionalized vision of the world aligned with her private belief system. If one wonders what she thought about life, suffering, faith, religious doctrine, and the South that she both embodied and reflected, all one needs to do is read her words—in my case, “A Temple of the Holy Ghost.” Her life is intriguing enough (and, in parts, inscrutable enough) that it will always attract biographers, but she wrote with such clarity that she was perhaps her own best biographer—sometimes in letters and journals, but not infrequently in her works of fiction, too.

Yet that has not discouraged multiple generations of O’Connor interpreters, expositors, and explainers. The latest, and perhaps least, such explainer is the actor Ethan Hawke, who has co-written and directed a strange and strained filmed biographical account of O’Connor called Wildcat. Ostensibly a reference to a 1947 short story by O’Connor, the title serves to advance the movie’s actual agenda: it is dead-set on presenting O’Connor as a woman stifled by her time and place who was bristling to emerge in her full untamed feralness—a view of her life that appeals to modern sensibilities but fails to capture her in full.

Hawke portrays O’Connor as a victim, a trapped creature of some sort.

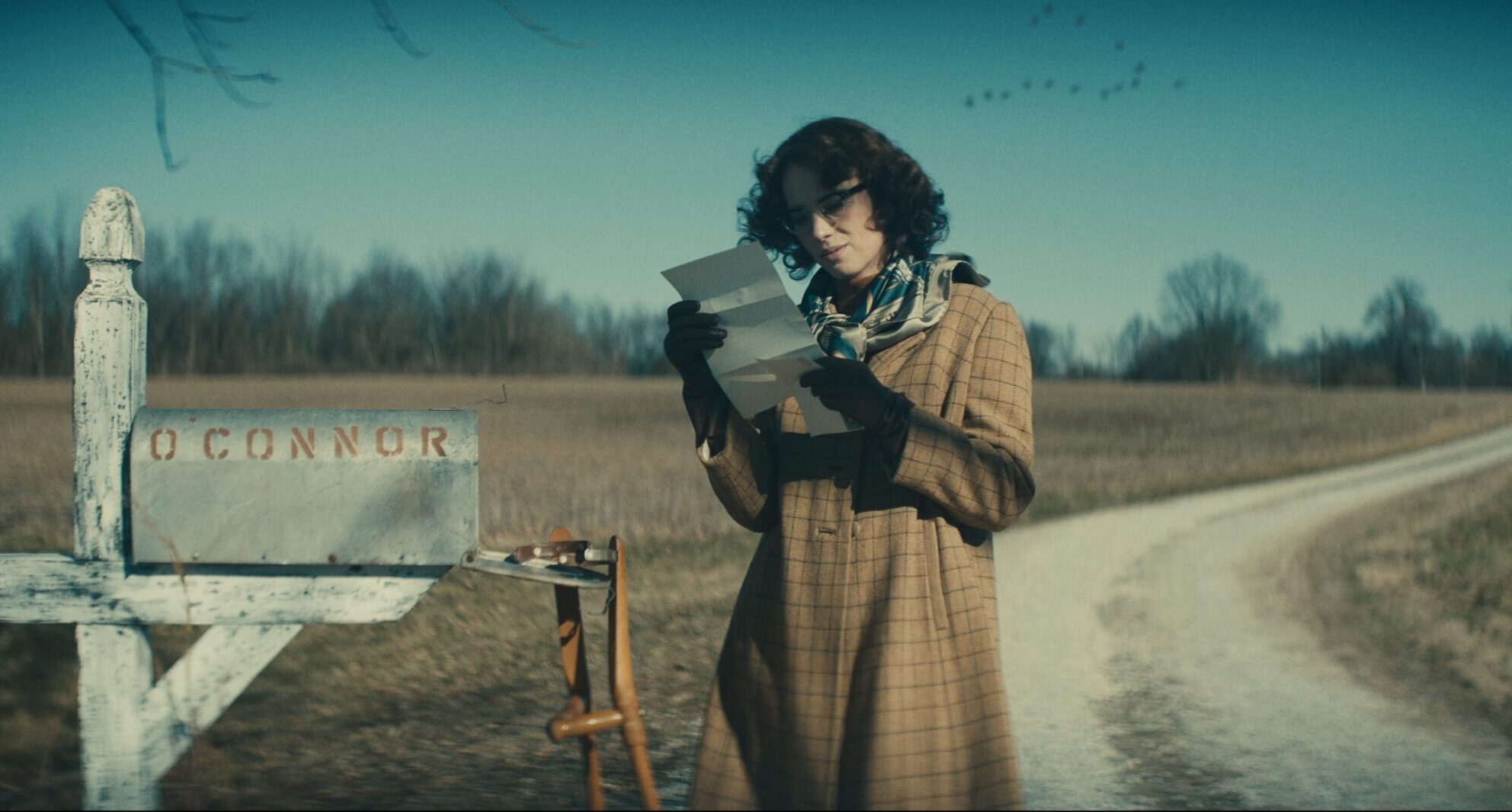

The movie, released by Oscilloscope Laboratories in May and now playing in theaters around the country, stars Hawke’s daughter Maya Hawke as Flannery O’Connor. In her favor, the actress bears a passing physical resemblance to the writer. Her weak, wobbly chin goes a long way to selling the characterization, though, like Marlon Brando in his screen test for The Godfather, she looks like she has Kleenex stuffed in her cheeks. But the external aspects of a performance can only carry an actress so far. Maya Hawke knows what O’Connor looked and sounded like, but like many performers playing personages from a past time they may find discomfiting, she can’t quite imagine what her subject was actually like. From those of us who know O’Connor through her words, Hawke’s embodiment of O’Connor seems too stern, too humorless, too defensive about having to explain to her mother, Regina, the importance of appearing in the Partisan Review.

By the same token, Ethan Hawke hits many of the key milestones of O’Connor’s early years: her stint as a student at the University of Iowa, her experience as a novelist in the making on the East Coast, and, after discovering the earliest signs of lupus, her permanent homecoming to Milledgeville, Georgia. Yet Hawke seldom gives the impression that he has a deep or intuitive understanding of O’Connor. By forcing her into a proto-feminist box, he misses, or understates, other aspects of her character, especially the depth of the Catholic faith that quieted her soul, nourished her intellect, and gave her the raw material with which to write. Hawke includes the occasional cursory scene of O’Connor praying or going to Mass, but her faith is usually presented decoratively rather than substantively, let alone dogmatically. It is taken as a given rather than rigorously contemplated.

Hawke is far more comfortable showing O’Connor as yet another victim of the 1940s and ’50s—moviedom’s favorite decades to target for their supposed complacency and conformity. The filmmaker gives us scenes of the writer being condescended to by the New York literary establishment while writing Wise Blood, coming to loggerheads with Regina (played by Laura Linney), or being flat-out misapprehended by folks back home in Milledgeville. All of these scenes have a basis in reality and can be justified on those grounds, but why these scenes and why this emphasis?

Instead of focusing on publishers who didn’t know what to do with O’Connor, why not highlight later publishers who warmly embraced her talent? Instead of portraying the bleakness of O’Connor’s initial return to Milledgeville, why not show the abundant internal existence she developed back home through correspondence, speaking engagements, and, above all, her church? Instead of giving furtive glimpses of her Catholicism, why not explore it more fully—by noting, for example, the way she encouraged her friend Betty Hester’s formation in the faith? And instead of dwelling on the onerous physical manifestations of her lupus, including her facial rash and reliance on crutches, why not find a way to visualize O’Connor’s actual view of sickness? “Sickness before death is a very appropriate thing,” she wrote to Hester in 1956, “and I think those who don’t have it miss one of God’s mercies.”

Every filmmaker depicting a real historical figure must select what to include and what to omit. Yet Hawke’s choices seem informed by his desire to make O’Connor’s story palatable to modern sensibilities. By stressing the challenges O’Connor faced as a female writer at midcentury, Hawke aims to place his subject into a framework that makes sense to contemporary, largely secularized audiences. In some ways, who can blame Hawke for wanting his heroine to come across more as a rebellious, independent-minded young woman than what would today be called a “trad” Catholic? Of course, O’Connor was both things, but the film makes her more one thing than the other, and that choice is a matter of making her more likable—more relatable—to moviegoers, something the writer herself, in all her prickly oddness, would never have countenanced.

When O’Connor is asked by a Milledgeville denizen, “You been writing any cute stories lately?” the obvious reaction comes too quickly and too easily: Of course we laugh at the lameness of the question. Of course we are mildly enraged at someone expressing such a crude misunderstanding of O’Connor’s artistic aims. And of course we empathize with O’Connor’s diffident, mildly contemptuous reaction—nicely played by Maya Hawke. But this moment is a sign of the movie’s simplemindedness; a more complex movie would not have made O’Connor such an easy source of identification with the audience.

Hawke portrays O’Connor as a victim, a trapped creature of some sort. One shot, photographed from above, shows her in a train station whose elaborately patterned tiles are meant to suggest a prison from which she is trying to escape. Granting that sexist attitudes existed in O’Connor’s time (as they do today), and granting that O’Connor’s lupus subjected her to a kind of confinement, such a shot makes the point too emphatically and too simply. The story of an O’Connor who was as trapped as the film suggests cannot account for the striking work she was able to produce, the patronage she received from Robert and Sally Fitzgerald, or the increasing attention and acclaim throughout her life.

Wildcat also suffers from a certain problem inherent in movies that attempt to dramatize the inner lives of writers. Even those I admire often include scenes that heighten the writer’s trade in phony, labored ways. In Fred Zinnemann’s Julia, for example, Jane Fonda’s Lillian Hellman is shown writing the play that becomes The Children’s Hour, but even if we accept that the play had a difficult birth, it doesn’t seem plausible that Hellman agonized over her creation quite so emphatically: Did she really heave the typewriter out of her window? Julia is an important and artful movie—and still not entirely credible.

Wildcat also dials up the drama, but even more dubiously. It attempts to compensate for the essential staidness of O’Connor’s existence by supplementing the main narrative of her life with highly condensed dramatizations of a number of her best-known short stories, including “Good Country People,” “Revelation,” and others. Sometimes, as in the case of “The Enduring Chill,” the stories’ contents seep into the main narrative. But in spite of the seemingly bold gambit of having Flannery and Regina embody her own characters, these filmed mini-stories are too numerous, too abbreviated, and too tossed-off to either add excitement to the main narrative or provide substantial insight into O’Connor herself. Instead of adding to the viewer’s understanding, they come across as a Classics Illustrated–style highlight reel, and Flannery and Regina’s presence in them seems like a gimmick.

Even some famous episodes from O’Connor’s life are needlessly embellished. For example, O’Connor fans will surely anticipate seeing a dramatization of that famous New York party when O’Connor stood up for the Sacrament of the Altar. At the party, after writer Mary McCarthy commented that she considered the Eucharist to be a “symbol,” O’Connor replied, as she recounted in a 1955 letter to Betty Hester: “Well, if it’s a symbol, to hell with it.” This is perhaps the finest, firmest remark ever made in support of the doctrine of the Real Presence in the Sacrament, and one that O’Connor pointedly told Hester required no further elaboration: “That was all the defense I was capable of but I realize now that this is all I will ever be able to say about it, outside of a story, except that it is the center of existence for me; all the rest of life is expendable,” O’Connor wrote.

Yet what O’Connor actually said—in its unyielding brevity—was not enough for the moviemakers. So, in Wildcat, Maya Hawke speaks O’Connor’s actual line (“Well, if it’s a symbol, to hell with it”) and then proceeds to elaborate with lines that O’Connor did not actually say to McCarthy but instead wrote in another letter, from 1959, in which she stressed “how much religion costs” and refuted the mistaken idea that “faith is a big electric blanket, when of course it is the cross.” These are wonderful insights, but to combine them with O’Connor’s actual remarks to McCarthy distorts her entire point in being so adamant yet so concise in her defense of the Real Presence: that, when it came to the Sacrament, she had very little to say except that it was Real and that it was essential to her existence.

To Hawke’s credit, O’Connor’s words are all over Wildcat, but as spoken they sound curiously out of tune. We hear, in a piece of concluding narration, a verbal stew made up of O’Connor’s actual accounts of her being compelled, by her illness, to pull up stakes for Georgia. “I stayed away from the time I was 20 until I was 25 with the notion that the life of my writing depended on my staying away,” she wrote to Cecil Dawkins. “I would certainly have persisted in that delusion had I not got very ill and had to come home.” This account is melded with another letter to Maryat Lee: “This is a Return I have faced and when I faced it I was roped and tied and resigned the way it is necessary to be resigned to death, and largely because I thought it would be the end of any creation, any writing, any work from me,” she wrote. “And as I told you by the fence, it was only the beginning.”

When read, O’Connor’s sentiments have the fullness of rich and complex thoughts—that there was both defeat and opportunity in her homecoming—but when heard, in somewhat reworked form and in the context of a movie that seeks to simplify rather than complicate its subject, they come across as another “girl power”–style awakening. Most regrettably, so does the film’s use of O’Connor’s signature symbol and favorite of God’s creatures, the peacock: in this final image, a peacock’s tail feathers are seen emerging behind O’Connor as she sits at her typewriter. This is not only a heavy-handed image but one that insists on this movie’s image of O’Connor as an alleged victim. The feathers are meant to represent—what? Wings? Liberation? Freedom of expression? O’Connor had all these things already—she was, after all, a temple of the Holy Ghost.