Liberalism strikes back in this issue of Modern Age. At a time when nationalism, populism, and newly assertive forms of traditional faith are challenging the political and economic order of the world, our authors consider what is living in liberal tradition—and what even nonliberals might find within it that is worth preserving in this age of upheaval.

Our literary editor, Samuel Goldman, leads off with an incisive look at the work of Yoram Hazony, in particular his new book, The Virtue of Nationalism. Hazony is one of liberalism’s leading critics today, but Goldman, a conservative for whom classical liberalism is not anathema, argues that the nationalism of the English-speaking world has always been tinctured with something of the spirit of John Stuart Mill, if not Immanuel Kant.

This classical liberal gene in the Anglo-American DNA is a source of congenital disease, according to the diagnosis Patrick Deneen supplies in one of the other key books of this year, Why Liberalism Failed. But the libertarian economist and historian Deirdre McCloskey offers an optimistic second opinion—liberalism and the capitalist economy associated with it have made possible human flourishing on a scale unimaginable in earlier times. That people today abuse their wealth and freedom, as people always have done when the means were available, is neither surprising nor an indictment of uniquely modern morals. Complementing this view, Ann Hartle argues in her essay that civility—a virtue now under siege by the postmodern left—has only been possible since the emergence of a civil and social sphere distinct from the state, a development whose beginnings can be found in the personality and thought of Michel de Montaigne.

The story of liberalism has its American chapters too, of course, and Kevin Gutzman in this issue reflects on one of the most important: the life and philosophy of Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’s understanding of society and politics is unfashionable today on much of the right as well as the left, and Gutzman ponders what is still “American” about the Sage of Monticello in the twenty-first century.

Russell Kirk, whose centenary approaches in October, is not a name one readily connects to liberalism. But he was no reactionary, as that term is understood by the hard right today. Jack Hunter reminds us that Kirk began his scholarly career by drawing our eyes back to an exemplary American Burkean who was also arguably more Jeffersonian than Jefferson himself—John Randolph of Roanoke. Hunter, a native of South Carolina and a former staffer for Senator Rand Paul, shows why libertarians no less than conservatives still need Russell Kirk and the humane, philosophical politics he championed.

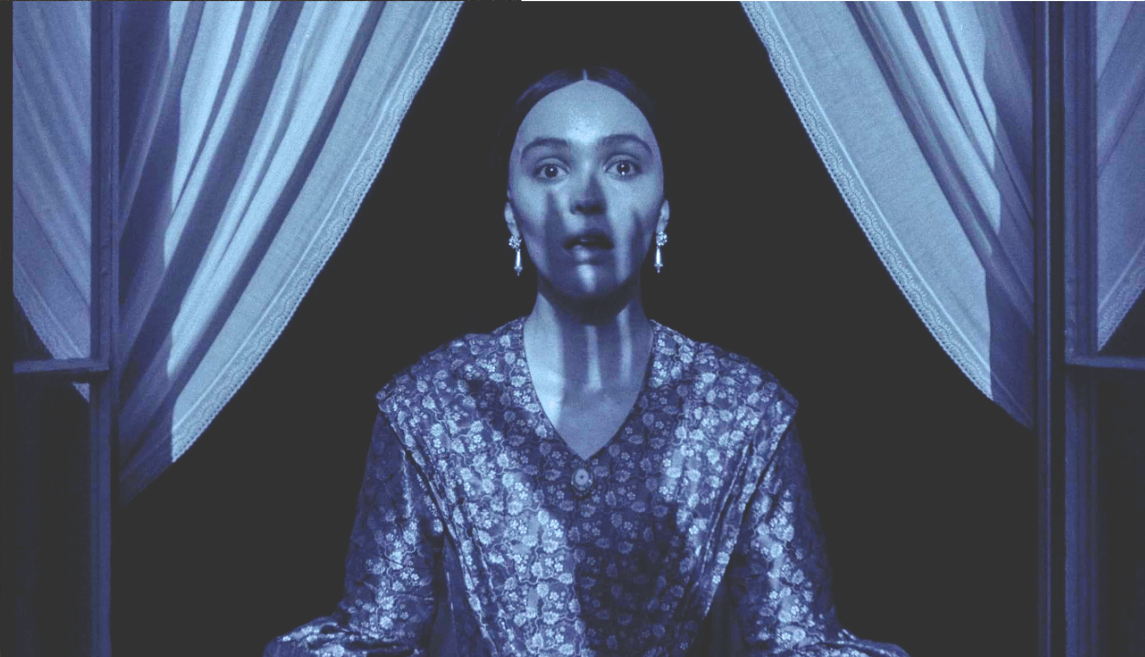

A less well-remembered side of Kirk, his achievement as a writer of supernatural fiction, is celebrated this issue by Scott Beauchamp, who juxtaposes to the nihilism of Lovecraftian horror the undeniable Presence of the good to be discovered in Kirk’s tales. The Permanent Things are not the things of politics or economics, whether liberal or otherwise, but the things of the spirit.

This year has seen a remarkable efflorescence of serious thought about the foundations of the Western order and the relationship that liberalism in all its forms bears to those foundations—questions explored in our essays this issue as well as in several of our reviews, including those that consider the fate of the “liberal order” and its rivals in foreign affairs. But the last word on liberalism, and even the specific works and theses under analysis in this issue, has yet to be written. Expect to encounter searching criticisms and serious alternatives to liberalism in future issues of this journal, as well as a continuing attention to the imperfection of all human designs.

Daniel McCarthy is the editor in chief of Modern Age.