“Perhaps we should rejoice in the disappearance of Canada. We leave the narrow provincialism and backwoods culture; we enter the excitement of the United States where all the great things are being done. Who would compare the science, the art, the politics, the entertainment of our petty world to the overflowing achievements of New York, Washington, Chicago, and San Francisco?”

Among Canada’s modest literary contributions, Lament for a Nation continues to stand out. Published in 1965, George Grant’s most well-known work is a 160-page essay with a simple thesis: Canadian nationalism has been defeated.

It appeared just two years after Canada’s 1963 federal election, in which the Progressive Conservative (PC) government of John Diefenbaker was defeated by the Liberals, who were aided in that victory by John F. Kennedy. President Kennedy detested Diefenbaker, in large part because of the latter’s refusal to allow American nuclear missiles to be placed on Canadian soil. At the time, the Liberals stood for Cold War internationalism and had the support of corporate Canada, while the PCs were backed by western Canadian populists and small-time business owners.

For Grant, the 1963 election was the last gasp of Canadian nationalism, asserting itself in the desire for an independent foreign policy. Diefenbaker’s defeat, then, was a coup de grâce for the extinction of a nation. Grant declared that the decline of Canada as a distinct, British American entity robbed it of purpose and independence and judged that Canada would be swallowed up economically, politically, and spiritually by the United States. Six decades after Lament’s publication, the first months of Donald Trump’s second presidency have both affirmed and challenged Grant’s assertions about the future.

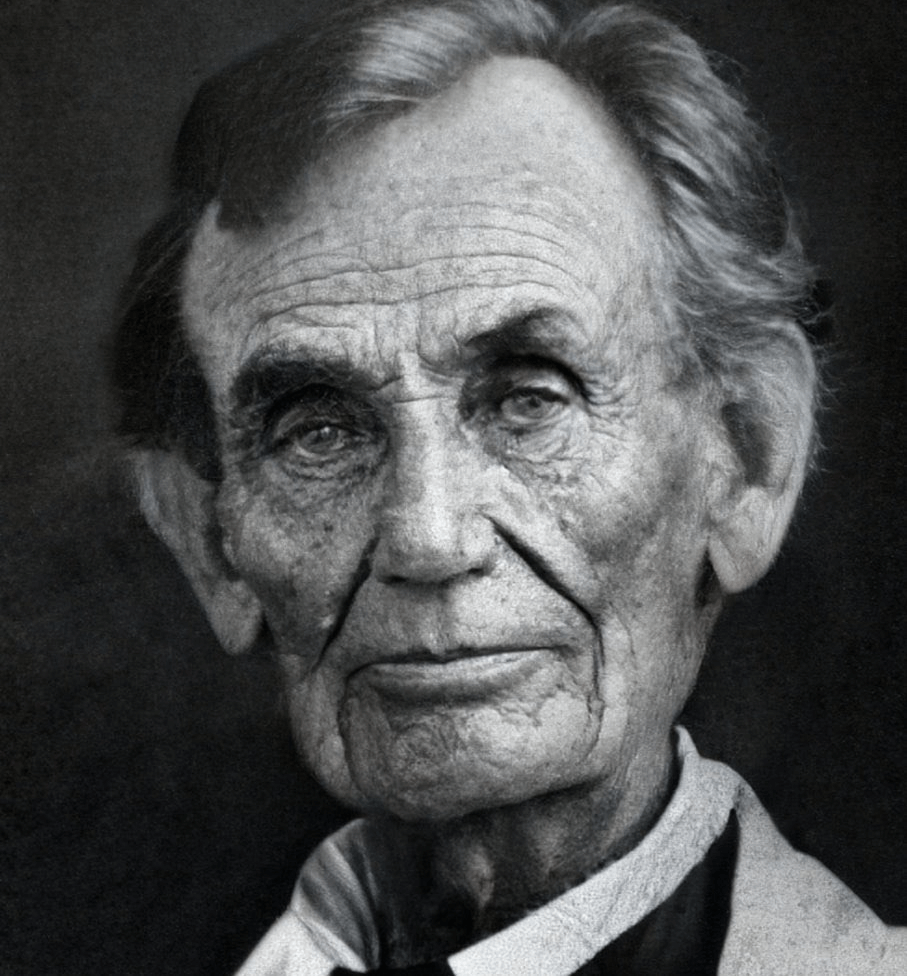

For one, Grant, a professor of philosophy and religion, believed the tide of American liberal modernity of his time was an unyielding force, as was the power of American industrial corporations spreading around the world. He died in 1988, so it can only be guessed what he might have thought of Trump’s economic nationalism, his socially and culturally conservative populism, and the retreat from unquestioning free trade. Perhaps he would have thought that a window has opened for Canada to rediscover a truly distinct identity and regain a measure of economic and political independence. But if such a feat proves impossible for Canada, Grant would hardly have been surprised.

To see why Grant was no optimist about his country, it is important to understand the Canada that he grew up in and cherished. The Grants were well-off Anglicans from Ontario with a long history of higher education and public service. Toronto, where Grant was born in 1918, was regarded as the “Belfast of Canada,” where the Irish Protestant diaspora and the Orange Order held a near-monopoly on political power. Whether Liberal or Conservative, every mayor of Toronto in the twentieth century until 1954 was an Orangeman. The city was decorated with Union Jacks and monuments to imperial adventures such as the Boer War.

Like many patrician Canadians, Grant studied at Oxford and lived through the London Blitz, which helped turn the young student into a deeply religious man. His Christianity was very important to his future Lament.

After returning to Canada, Grant began an academic career that took him to Ontario and Nova Scotia. Among his contemporaries was the historian Donald Creighton, and it is remarkable that there is no recorded instance of the two ever actually meeting, given their similar interests in Canada’s politics and economy. Still, their shared concerns are well worth exploring in parallel to one another.

Creighton wrote sweeping histories of Canada that focus heavily on economics. His first major work, The Empire of the St. Lawrence: A Study in Commerce and Politics, traces colonial Canada’s failed efforts to turn the St. Lawrence River into the backbone of a commercial empire. It concluded gloomily in 1849 with the liberalization of Britain’s imperial trade laws, which enabled manufacturers and consumers to buy goods and materials wherever they were cheapest and thus hit the colonies very hard. Creighton’s two-volume biography of Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, came next and serves as a sequel of sorts. It rightfully portrayed Macdonald as the force who united the colonies into a federation in 1867, giving British America a renewed purpose.

Grant also praised Macdonald as vital to Canada’s story. The former is often described as an adherent of Red Toryism, an ideology grown from the branch of British One Nation conservatism, as championed by Benjamin Disraeli. It rejects individualism as the basis for governance and seeks to defend and preserve organic societies. Grant considered this view to be a form of nonrevolutionary socialism for conservative ends, namely, the conservation of Canada itself. He described the power of government as one of the few bulwarks in Canada against the homogenizing corporate power from the south.

This opinion shows how relatively recent is the alignment of Canadian conservatives with free market ideals. Not so long ago, theirs was the faction that favored government monopolies for sectors such as energy and transportation services. They followed the spirit of Macdonald, whose government sank millions into constructing transcontinental railways in the nineteenth century to secure the fledgling country.

Opposite the Conservatives were the Liberals, who then endorsed limited government and freer trade with the United States. By World War II, the Liberals had gained the vital position as Canada’s natural party of government. Creighton despised the Liberals for progressively distancing Canada from Britain and moving the country closer to the United States. In fairness, the British themselves had little interest in old imperial connections after World War II as their empire began to disintegrate. What good was Canada as a British American redoubt when Britain itself was more interested in cementing its “Special Relationship” with Washington?

Creighton, who also was a speechwriter for Diefenbaker, warned that the domination of foreign companies in the natural resource sector rendered Canada into a mere economic vassal, with little of the profits going towards Canada itself.

Similarly, in Lament, Grant saw Canada’s future as a “branch-plant” economy where American corporate giants dominated local industry, leaving little for the native hands. He foresaw Canada’s fate as permanently tied to the United States, relieving it of any agency to truly shape its own future.

Grant classified postwar liberalism and its emphasis on freedom and progress as a flattening, homogenizing force that would also drown Canadian culture, which he readily admitted was brittle and provincial. He extended this argument to the United States, as well: When he expressed his sympathy for the five southern states that voted for Barry Goldwater in 1964, it was not due to support for segregation or Goldwater’s libertarian ideals but because he saw those five states as attempting to defend a distinct, local culture in defiance of Great Society liberalism.

Back in Canada, then, what was that distinct identity that Grant described as frail and backwoods? To answer this question, he looked to the Loyalists who rejected the American Revolution and migrated north to the remaining British colonies. He identified the Christian, communitarian thought of the Anglican theologian Richard Hooker as the source of Loyalist ideals rather than John Locke’s liberalism. Canada, according to Grant, was intended as a sober redoubt of order that challenged the march of Jacksonian ideals in the United States. In this sense, Red Tories like Macdonald and other Canadian conservatives embodied this ideal of a sterner, more heavy-handed but ordered alternative.

And in many ways, he was right about modernity’s devouring of Canadian culture. By 1954, Toronto elected a mayor who did not belong to the Orange Order. In 1965, the same year Lament was published, Canada adopted the red Maple Leaf flag, replacing the Red Ensign, which was adorned with the Union Jack. Canadians seemed to be attempting to adopt a wholly progressive worldview, looking only ahead and primarily south of its border. There was little pause or inward reflection on what it meant to be Canadian as they drank Coca Cola and watched the Ed Sullivan Show. It was earning its nickname as “America’s Hat” or, worse, “Diet America.”

By comparison, the Loyalist heritage appeared almost medieval, if not vestigial. Modernity and American liberal optimism seemed eternal, with a figure like Trump and his more protectionist, America First politics impossible to imagine.

What would Grant have made of the Trump era? Trump is the greatest challenge so far to the postwar order that Grant criticized, and he may well finish it off. This would certainly challenge Grant’s assumptions about the inevitability of an American-led liberal world order. For this reason, Grant may have seen Trump’s presidency as a good sign.

Yet the possibility of Trump’s tariffs wreaking havoc in an economic war would be disastrous for Canada’s economy, exposing the vulnerabilities of integration with the United States. So Grant may have lamented about Canada’s continued inability to fully assert its own national identity.

And indeed, the country seems unprepared to revive any authentic sense of Canadian nationalism. For the incumbent Liberal government, asserting Canadian identity in recent weeks in the wake of Trump has amounted to doubling down on slogans like “inclusivity” and acting as the foil to Trumpian populism.

A genuine Canadian nationalism remains elusive, but there has always been a cadre of Canadians who cherish the country’s history and culture. Perhaps their time has finally come. If so, their efforts are sorely needed.

But whatever happens to Canada, Grant knew it wasn’t his final home. He led a thoroughly Christian life and always reminded his followers and readers that there are powers beyond time and space: “The kindest of all God’s dispensations is that individuals cannot predict the future.”