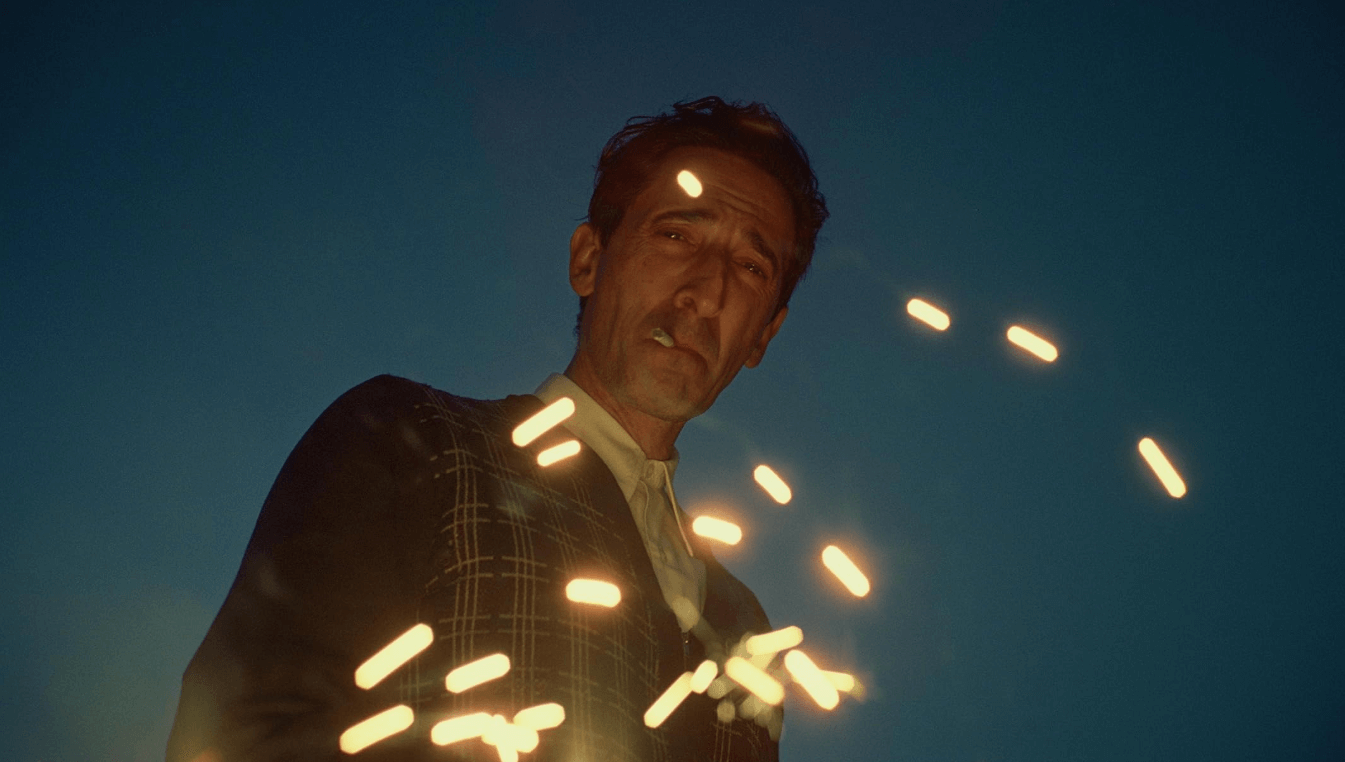

I am struggling to recall a film that made me as angry as The Brutalist did. The top-tier contender for Academy Awards Best Picture directed by Brady Corbet and starring Adrien Brody as the fictional modernist architect László Tóth, who survives the Holocaust, comes to America after the war, toils in undeserved obscurity until being plucked therefrom by a wealthy industrialist who commissions him to build a complex that will make his name enraged me in a way that is entirely out of proportion to the ultimate significance of the film—or, arguably, of any film.

After all, I’ve seen plenty of movies lately that irritated me or that I thought weren’t any good. I wrote in Modern Age about a number of such disappointments from 2023, including Napoleon, Ferrari, Priscilla, Maestro, and Killers of the Flower Moon (along with one film that did not disappoint me, Oppenheimer). At the 2024 New York Film Festival (which I wrote about here), I was profoundly disappointed in Paul Schrader’s film, Oh, Canada, to the point where I was downright annoyed that it had been programmed. I remember how irritated I was in 2018 that films like Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri and The Shape of Water—neither of which I liked or considered to be serious films—seemed to have a better shot at going home with an Oscar than fellow nominees like Get Out, Lady Bird, and Phantom Thread, all of which I thought were far superior.

None of these films made me angry though the way The Brutalist did. I’m trying to understand why.

I know it has something to do with both the level and type of praise that the film has garnered, which I feel is entirely undeserved. The Brutalist isn’t just being called a powerful or important film; it’s being called an epic, a monumental achievement, a landmark. Myself, I found it poorly written, dull, and massively overlong, but also the opposite of epic, both small-scaled and small-souled. But I don’t think the degree of my disagreement is the whole reason or even a particularly central reason for my rage. It’s not just that I think the emperor has no clothes. It’s that I think he’s prancing around naked and urinating in our faces—or in my face specifically. It feels personal.

Let’s start, though, with matters that are less personal. The writing is consistently heavy-handed, clunky, and shot through with glaring anachronisms. When Harrison Lee Van Buren Sr., Guy Pierce’s 1950s-era WASP industrialist, refers to Erzsébet (Felicity Jones) as László Tóth’s “significant other” I almost walked out. But even when they don’t sound like they are who they are or when they are, the characters in The Brutalist never sounded, to me, like real people, from any place or time. They sounded like walking symbols.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the depiction of László Tóth’s black friend, Gordon (Isaach De Bankolé), who appears to be his only friend. But is “friend” the right word, exactly? László meets him in a bread line, where he does him a kindness, then proceeds to hire him, to invite him to his home—an extended series of kindnesses. At points they also work together as equals, and Gordon introduces László to both jazz and heroin, so it’s not all one-way beneficence. But who is Gordon? We have no idea. The film doesn’t have the slightest curiosity about him as an individual human being. He exists in the film primarily to show that László doesn’t share the racial prejudice that is rampant among American whites.

The film is being lauded above all for its visual style. A single image, early in the film, exemplifies this: the Statue of Liberty viewed upside down. The symbolism, again, is thuddingly obvious and also completely unearned; we’ve seen no evidence yet that America’s promise is, in any way, false or about to be betrayed. But more to the point: whose view is this? Visually, I mean. Not László’s. Immediately before we see the statue upended, we see the Hungarian refugee’s face. He’s not looking upside down; he’s looking at the statue entirely normally. But after we pan away from him, the camera turns upside down, and now we get that vertiginous view. The shot, in other words, is entirely artificial, a view from nobody—or, rather, the view of the director telling us how we’re supposed to look at things. That’s a spirit that pervades the entire film.

I said that this supposedly epic film to me felt small-scaled. László Tóth comes to America at a moment of extraordinary ferment, into its most crowded city and its busiest port. There is no sense of this, no sense of energy, of crowds of the future happening in this place. When Tóth quickly leaves New York for Philadelphia, he might as well be moving to a small town; there’s no sense of the city at all. Even at a smaller scale, this world feels empty. We see Tóth go to a synagogue, but we never see him forming relationships of any kind with the other worshippers there (who, I will note, chant in historically inappropriate accents). We don’t even see the synagogue properly; it’s merely suggested, as it were out of the corner of the camera’s eye.

Perhaps this is Corbet’s way of saying that America doesn’t want to see this Jewish presence clearly, but I suspect more practical considerations. Shots throughout the film are routinely framed so as to avoid revealing a world that hasn’t been dressed for the period, but the consequence is that we barely see that world, are barely aware it exists. You don’t need crowds to make an epic, of course; 2001: A Space Odyssey is mostly empty; Lawrence of Arabia makes much of vast, uninhabited vistas. But emptiness is as integral to those worlds as crowdedness is to the world of The Brutalist, and yet Corbet simply doesn’t show it to us.

The film gestures at the idea that his characters might have interesting inner lives, only to veer resolutely away toward something more banal and superficial. Often, these swerves involve sex. When he first gets to Philadelphia, László Tóth is taken in by his cousin, Attila (Alessandro Nivola), who came to America some years earlier and has assimilated, shedding much of his accent and marrying a nice Catholic girl, Audrey (Emma Laird). There’s a scene where Attila, László, and Audrey have all been drinking at home, and Attila begins pushing his cousin to dance with his wife. László demurs, repeatedly, and Audrey herself expresses no interest, but Attila won’t let it go. “She’s waiting for you,” he keeps saying. I don’t know what Corbet intended with the scene, but on the surface it felt an awful lot like Attila was pushing his cousin to sleep with his wife—which, I thought, could be interesting! But no. Instead, the next morning we find out that Audrey has accused László of making a pass at her, and so Attila throws him out on his ear—and takes himself and Audrey out of the movie. For what reason did she made this false accusation? She wanted Tóth out of the house, we are led to believe, because he was too obviously Jewish. How unimaginative.

Another example: when Erzsébet, after many years of separation, is reunited with her husband, she desperately wants him to touch her, sexually—but he won’t do it, and seems inexplicably angry at her very presence (something Erzsébet can’t fathom either). We already know from an earlier scene that László has been unable to perform sexually with a prostitute, so we’re led to believe he has some kind of problem. Are we going to go deeper into this? Is this a post-traumatic response? How is Erzsébet going to deal with a largely sexless marriage? We don’t know—and Erzsébet never manages to ask; she simply repeats, endlessly, how worried she is that she no longer attracts him because she is now disabled (a consequence of hunger during the war), that she has grown older, and that she knows what László has done (cheat on her, presumably) and isn’t jealous. We have acres of time to explore this marriage, and we never really get beyond this opening position. Tóth’s impotence is symbolic, not substantive.

If Tóth is symbolically impotent, the Van Buren men are symbolic sexual predators. It is strongly suggested that Harry Jr. (Joe Alwyn) molested László’s mute niece, Zsofia (Raffey Cassidy), and on a trip to Italy to buy marble for the altar of a chapel the elder Van Buren has commissioned, he drunkenly rapes László (or, at least, grabs him on a mattress and rubs up against him to the point of climax; the two men appeared to me to be fully clothed throughout). There have been suggestions all through the film of a kind of attraction to László on Van Buren’s part, something that might be but doesn’t need to be sexual. The elder Van Buren seems to have aesthetic yearnings but to lack either taste or talent, and he fastens on László as a means of satisfaction. It’s potentially interesting, and the film could have chosen to explore the inevitably fraught relationship between patron and artist. Instead, it is very typical of this film to make that metaphor brutally and simplistically literal, and thereby flatten their relationship into one that is pure exploitation and abuse.

And what about László Tóth’s aesthetic yearning? It is downright astonishing to me that, in this film supposedly about a visionary modernist architect, we get no sense of his actual ideas. We know he trained at the Bauhaus, but what did he take from that training, and where has he taken it? Modernism, like everything else in the film, is presented purely as a symbol, a signifier—of taste, of culture, of progress. László has it; the Van Burens don’t, but covet it. But what is it? The film hasn’t the slightest interest, any more than the Tóths seem to (they are the least intellectually engaged intellectuals I’ve ever seen depicted, never once reading a book, discussing the news, even going to the movies; they seem literally to have no lives).

The film appears to be convinced that these things—taste, culture, progress—have no content of their own, but are actually just responses to historical trauma.

But it’s worse than that, actually, because the film appears to be convinced that these things—taste, culture, progress—have no content of their own, but are actually just responses to historical trauma. In an epilogue, we learn that Tóth’s monumental work that he has been working on for the entire second half of the film—the community center and chapel on a Pennsylvania hillside that Van Buren commissions—wasn’t an expression of some transcendent idea about form and function, the purity and egalitarianism of simple, cheap materials like concrete (as the historic architectural movement known as brutalism actually was), but rather an expression of Tóth’s suffering in a German concentration camp. Tóth enacted a literal replication of the camp’s dimensions on that Pennsylvania hillside, transforming the most forward-looking movement in art history (for better or worse), into the most backward and inward-looking, and transforming the aesthetics of ultimate brutality into . . . well, I’m not sure into what, because the structure we see rising in Pennsylvania remains as punishing and unappealing as you would imagine something birthed in a concentration camp might be.

All of this is totally false to the history both of the brutalist movement—which I have no particular interest in defending; I’m delighted that ornament and human proportions are no longer dirty words in architecture—and false as well to America’s historic relationship to the exiles who belatedly washed up on our shores in the wake of the Nazi mass murders. I fully endorse every part of Justin Davidson’s trenchant critique of the film from this perspective. The film’s false history doesn’t even make sense in its own terms, though; Tóth’s first work for Van Buren supposedly gets profiled in a major magazine, and yet he never even considers how he might to parlay this into other jobs? Tóth’s bizarre sense of dependence on Van Buren could, again, have been interesting if the director were willing to explore or at least acknowledge it as an aspect of his character. But he isn’t and he doesn’t, because he has a point to make—a point about America—which nothing potentially interesting will be allowed to interfere with.

And this is why the film felt to me like a personal insult. No, The Brutalist is not a Holocaust film, not a serious one at any rate, because it has no real interest in the experience of the camps, or of the survivors thereof, or in Jews more generally, any more than it does in architecture. (I don’t even understand how Tóth and his wife, both Hungarian Jews who would have been shipped to the death camps Auschwitz and Birkenau, instead wound up in German concentration camps Buchenwald and Dachau respectively, nor how, if they were both liberated by the Americans in 1945, they could not be reunited in the two years before László shipped off for America. None of the history in this film is ever made clear.) The ostensible subjects of the film are just useful symbols for demonstrating America’s essential perfidy. America didn’t want these people, except as tokens to acquire the taste and class that we utterly lack in and of ourselves, and at the first chance we will literally rape and pillage them. That’s the film’s message, hammered home in virtually every scene that could have been used to explore these people’s actual experience, and give them a proper subjectivity.

I resent that, deeply, and I think that’s why this film actually made me angry instead of just annoyed or disappointed. I resent treating Holocaust survivors merely as symbols, I resent treating America merely as a symbol, and I especially resent the brutality with which those symbols are deployed against each other in this film. For that matter, I resent how Israel is turned into a thudding symbol by this film. Israel keeps coming up—at one point we hear David Ben-Gurion reading Israel’s Declaration of Independence; at another a Jewish lawyer uses a snippet of Hebrew to speak to Tóth (though Yiddish would make far more historic sense); later in the film Zsofia and her fiancé declare their intention to move there, and later still Erzsébet declares her intention to join them. But Israel isn’t a real place with its own real history, nor even a place that American Jews are fascinated with and debate about. It’s an abstraction, the only solution to the problem that Americans, no less than the Germans and other Europeans, are inveterate antisemites—or, perhaps better but not really that different, that László Tóth wants his chapel’s ceiling to be a certain height, and the guy who commissioned the building will not appreciate why that is so important to him.

I don’t think anyone needs anyone’s permission to make art about anything. I want to smash our current identity silos to smithereens. And I try not to moralize, even about Holocaust films; I’m on record on that subject as well. So if Brady Corbet wants to make a film about Holocaust survivors, gezunterheyt. But if your film reveals that you don’t really care at all about them, but just see them as handy excuses to beat up on my country in ham-fisted ways, you can’t expect me to say no worse than “it wasn’t for me” or “I don’t see what the fuss is all about.” If you want me to show you a minimal level of respect and not conclude that your only interest is borrowing the seriousness of your subject to falsely elevate your work, the least you could do is show that level of respect to your own subject.

Now, I recognize that I might wind up with egg on my face for taking such a strong stand against the critical consensus. It’s happened before, and it can happen again. The first time I saw Mulholland Drive, as my friend and I left the theater he said “that was arse” and I didn’t disagree with him. But while I still don’t think it’s one of the ten best films of all time, my opinion of David Lynch’s film has risen considerably, and I feel a bit ashamed now of not getting it at first. I saw The Beast recently, which I didn’t think was all that, and I worry it may follow a similar trajectory from cult hit to canon and that, in the fullness of time, I will once again come to be chagrined about my prior opinion. You have to take that risk, or you’ll never develop a critical sensibility in the first place—you have to commit to your opinions and take your licks, including possibly deciding that you were wrong.

This doesn’t feel like that, though. If I’m wrong about The Brutalist, I don’t know what I could possibly be right about. If the chorus of cheers for this film don’t fade, but rather swells over time, I might turn into one of those angry old men yelling at a world turned upside down.

This essay was previously published in Gideon’s Substack.