What’s Jordan Peterson’s favorite Bible story?

The Canadian psychologist and cultural commentator’s new book provides commentary on Old Testament stories, expanding on his last two works, 12 Rules for Life and Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life, which have helped make him a go-to self-help guru for a generation of young men.

In his new book, We Who Wrestle with God, Peterson analyzes the story of Cain and Abel as an archetypal story, one he says is perhaps the densest in meaning in all of Scripture. In his interpretation, Genesis and the stories of Moses and Jonah show that man has within his power to transform himself and become like God if he is only willing to take up responsibility and make the proper sacrifices.

The story of Cain and Abel is brief and powerful. The brothers each offer a sacrifice to God: Abel, a shepherd, offers choice meat while Cain, a tender of the fields, offers God the fruits of his harvest. God is not pleased by Cain’s sacrifice and warns him that he is headed down the wrong path. Cain responds in anger, killing Abel out of envy.

“The story of Cain and Abel therefore has a significance that extends directly into the political,” Peterson writes. “It constitutes the pattern for the victim/victimizer narrative that plays such a key role in the ideologies of resentment that so truly characterize our time.” The fact that this struggle resonates today, Peterson writes, proves this story to be “eternal.”

For Peterson, Westerners are subject to the temptations of bitterness and jealousy, both because of the richness of their civilization’s patrimony and the realities of human nature. Families, institutions, and nations are collections of the vices that spring from the human heart, Peterson says, and therefore any reforms ultimately depend on the individual.

While Peterson correctly identifies our human weaknesses, his solution leaves much to be desired. For him, the solution to the soul’s defects as described in the story of Cain is simply to perform the necessary sacrifice and to engage in struggle, a struggle with God.

The story of Cain lends itself to this interpretation—to a point. The text hints that God’s displeasure stems from the fact that Cain fails to give the proper sacrifice. Peterson notes that Cain’s offering of fruit “echoes the divine prohibition against consuming the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil” and that he displeases God because he wants “to usurp the right to create that moral order.”

While Peterson correctly identifies our human weaknesses, his solution leaves much to be desired.

In contrast, Abel’s offering is accepted because he “works honestly and hard, sacrificing most diligently and completely, offering what is both firstborn and of the highest quality.” Unlike Cain, Abel understands that reality has changed for mankind—we no longer live in paradise, and existence now requires struggle and sacrifice.

Cain, like his parents before him, has tried to become the arbiter of the good, failing to recognize that the structure of reality has changed—he is no longer in the garden, and God requires real sacrifice from mankind.

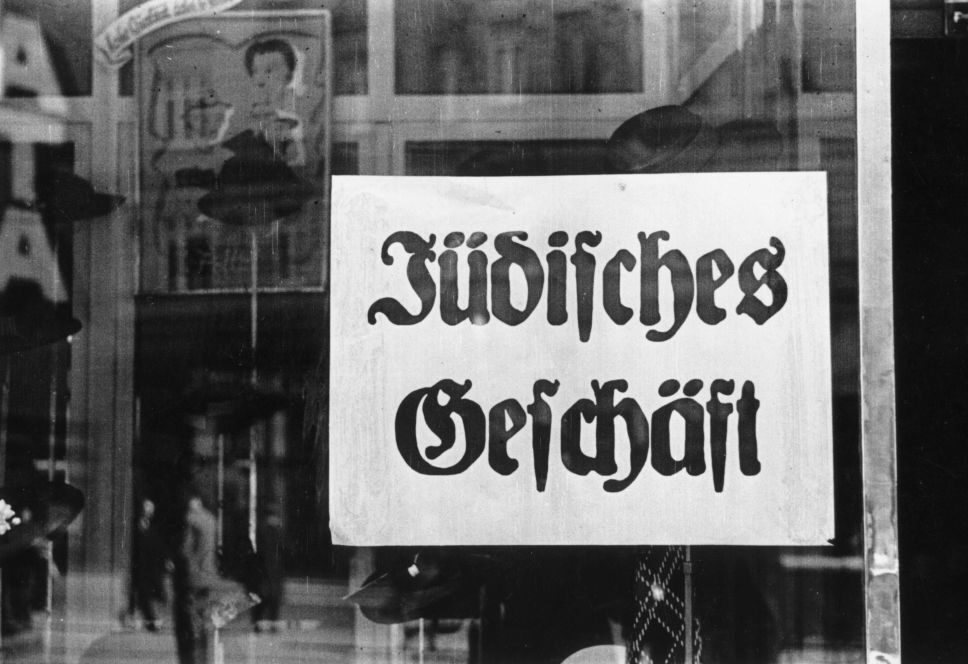

For Peterson, Cain’s actions foreshadow the utopian delusions of totalitarianism. Cain reveals his false belief that man can ignore the reality that mankind has been cast out of the garden and his world is no longer perfect; it requires struggle with man and sacrifice to God. Cain is unwilling to truly sacrifice—and once he is confronted by God for this failure, he sets off to kill his brother Abel out of envy.

The murder of Abel is the first instance of a utopian vision leading directly to death, and it signals the birth of the totalitarian soul. Peterson claims Cain as the “spiritual” forerunner to evil archetypes throughout history, calling Karl Marx “Cain to the core.” “Cain enters into a creative union with the spirit of sin and renders himself murderously vengeful,” Peterson writes. “He does so, instead of changing—instead of undergoing a transformative metanoia; instead of confessing, repenting and determining to do better, even when called out by God Himself.”

Totalitarians try to reconstruct the good into their own prideful vision. When that inevitably fails, they often strike out to kill those who attempt to recognize reality as it truly is. Peterson ends his section on the Cain and Abel story by emphasizing this fact: “The turning away from God and the failure to sacrifice properly corrupts and degenerates and, simultaneously, motivates the efforts of the prideful intellect to build structures that obviate the need for God and the burdensome moral striving that relationship with Him requires.”

Peterson nails most of the symbolism and especially the political significance of the story, but when his analysis is applied to man’s ultimate end, it falls short. This becomes clear in the story that Peterson offers as the corrective for Cain’s tragedy: that of Jacob’s wrestling with God. In the section that gives the book its title, Peterson claims that it is man’s attempt to make the proper sacrifice and willingness to wrestle with God that leads to his salvation.

In the biblical story, Jacob encounters a mysterious man whom he wrestles with until daybreak. The man turns out to be an agent of God, and though Jacob is permanently wounded he is renamed “Israel,” making him the namesake of God’s chosen people. “This transformation proceeds to a point so revolutionary that the men who undergo [it] are in some sense reborn,” Peterson writes. “If that wrestling is done in the proper spirit, there is no difference whatsoever between those two newly bestowed, fully integrated, and properly sacrificial identities.”

Later, he adds, “We are therefore by necessity those who wrestle with God. If we do that while gazing heavenward, we can align ourselves with the reality that is eternal and walk with God while we keep and dress the paradisal garden . . . we can have the redemptive romantic adventure of our life, transforming ourselves as we do so into the giants who once walked the earth.”

This conclusion demonstrates Peterson’s own personal struggles with God, why he has not made, at least publicly, the leap of faith, and the failure of his interpretation of Scripture. For Peterson, Scripture is a self-help manual for personal transformation through personal effort, not a call to personal faith. In a debate this fall with the evolutionary biologist and atheist Richard Dawkins, Peterson was pressed on whether he thought Jesus was a real person. He responded, “There are elements of texts that I am incapable of fully accounting for. I can’t account for the fundamental reality and the significance of the notion of the resurrection.”

Peterson’s inability to see Scripture as more than a symbolic text makes his analysis incomplete. Like Cain, Peterson asserts that man can make his own paradise on Earth if he only makes the proper sacrifice. But the Christian vision, so essential to the Western civilization that Peterson claims to defend, offers more. Many Christians interpret Abel as a foreshadowing symbol of Christ, the Good Shepherd who makes the perfect sacrifice acceptable to God. In this richer view, the story of Cain and Abel is not only the story of good and evil battling out within the human soul but the story of how sin has fully corrupted humanity. Like Cain, we can offer sacrifices and prayers as our path to salvation, and it will not be enough: we will still lash out at the world because the gap between God and us is that great. No number of Peterson-style exhortations to try harder, make your bed, and “be a bigger man” will change that reality.

But in the biblical story, God offers more than Peterson does: he grants a pathway to redemption for Cain. God tells him that his brother’s blood is crying out from the ground. In many Christian interpretations, his brother’s blood is the foreshadowing of the Son of God, the only one who could gain the full satisfaction of God that mankind seeks.

Peterson sees the stories and his interpretations of the Genesis and Moses stories as a roadmap for his audience of primarily young men. The heroes in these stories are men like Abraham who seek adventure and take up the responsibility to redeem the world through their own acts of heroism. It’s these small acts of heroism, not faith, that ultimately lead to salvation for Peterson.

While Christian readers might find this conclusion to be limited, Jordan Peterson’s new book is still a work worth wrestling with.