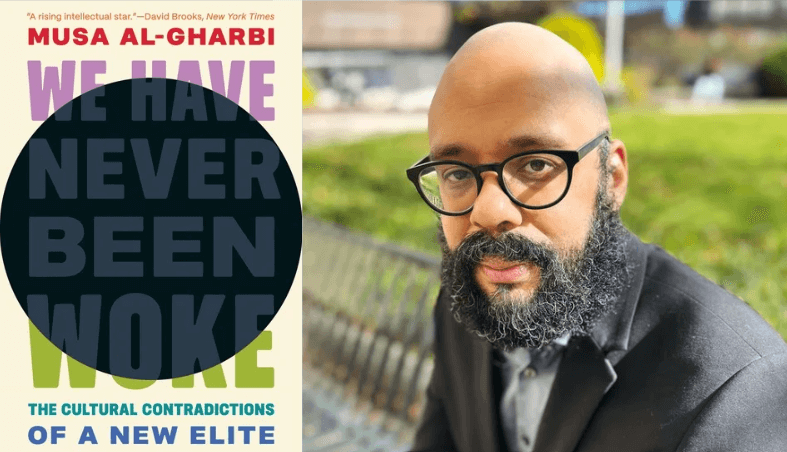

Today’s “Great Awokening” is not the first time the media, academy, and other “symbolic capitalist” professions have adopted a seemingly compassionate ideology as a means to entrench their own status. In his new book We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite, Musa al-Gharbi—an assistant professor of communication and journalism at Stony Brook University and a former Paul F. Lazarsfeld Fellow in Sociology at Columbia University—examines the motives and methods of the knowledge economy’s winners as they embrace a self-serving, yet sincere, new moralism. Modern Age’s Gene Callahan recently interviewed Professor al-Gharbi. Below is a lightly edited transcript. —ed.

Gene Callahan: First of all, let me say congratulations on writing such an excellent book.

Musa al-Gharbi: Oh, thank you.

GC: There were a couple of things that perhaps I disagree with you on. But the wealth of material you assembled in defense of your thesis is really impressive. How long did you work on this?

MA: Longer than I had planned to. But that’s because I actually ended up writing two books.

Basically, what I wanted to do in the initial pitch to Princeton was to spend about half of the book looking at “symbolic capitalists” and the social order that we preside over and the ways we legitimize our power grabs.

Then in the second half, I was going to turn the analytic lens from the winners in the knowledge economy towards those who perceive themselves to be the losers. I was going to look at people who are sociologically distant from us, people who are living in small towns or more suburban areas, or people who live in more rural areas, people who do jobs where they’re providing physical goods and services to people.

The basic argument of the second half was going to be that a lot of political things that we think of as separate stories—the diploma divide, the urban and rural divide, and the gender divide—are all proxies for this more fundamental divide in American society, which is between symbolic capitalists and people who feel alienated from the social order that we preside over.

Then I was going to argue about things like the rise of populist leaders like Trump or the crisis of expertise or tensions around identity politics: these are, similarly, different fronts in the same struggle, which is the real struggle between symbolic capitalists and people who feel alienated from their world. That’s going to be a second book—it’s probably going to be called Those People.

GC: Perhaps it would be good to do a little intro to what a symbolic capitalist is, and what you see as the cultural contradictions of this new elite.

MA: Symbolic capitalists have been known by other names by other scholars. They’ve also been called the “professional managerial class,” the “creative class,” the “New Class”—there are a whole bunch that involve “class.” I don’t think they actually combine into being a class in the traditional way that class was understood; that’s one of the reasons I didn’t stick with one of the existing terms.

Basically, symbolic capitalists are people who make a living by manipulating symbols and data—rhetoric, images, and things like this. These are people who don’t provide physical goods and services to people. If you want a nutshell way to think of who symbolic capitalists are, think about people who work in fields like science and technology, education, finance and consulting, law, human resources, et cetera.

The book is trying to highlight the cultural contradictions of the new elite. The core one, probably the one that anchors the rest, is the beginning of these professions—when they started to form into professions as we understand them today. This was in the period between World War I and World War II. Starting then, and accelerating after the 1960s and the move away from the centrality of industry, we saw the rise of symbolic capitalists, who started gaining more affluence and influence over society. The global economic order shifted in favor of the symbolic professions and away from traditional industry. One of the things that’s interesting about that move is that we symbolic capitalists, from the beginning of our professions, defined ourselves in terms of altruism and serving the common good.

Let me look at my own professions: Journalists are supposed to be a voice for the voiceless and speak truth to power, and academics are supposed to follow the truth wherever it leads, to tell the truth without regard to economic and political considerations. If you look at who in America is most likely to self-identify as an anti-racist, as a feminist, as an environmentalist, as an ally to LGBTQ people, it’s most likely to be symbolic capitalists. Who[ever] is engaging in the modes of discourse and self-presentation and interaction that people call woke are symbolic capitalists.

What you might expect, given our strong social-justice orientation that has been present since the beginning of our professions, is that as people like us have more power and influence over society, we would see a lot of social problems being ameliorated. We would expect to see growing trust in institutions as a result of all the great work that we’re doing. Instead, we see the opposite. In many respects a lot of social problems have persisted or even grown worse.

We see increasing institutional dysfunction, increasing distrust in institutions, increasing social mistrust, and growing affective polarization. So the core question the book is trying to wrestle with is, what’s going on here? Why do we see what we see, instead of what we promised and expected and maybe hoped would happen as we got more power over society? There are a number of subordinate puzzles that the book is wrestling with, but that’s the core one.

GC: I have two follow-up questions to that answer. The first is, why do the symbolic capitalists not form a class?

MA: One of the things that makes us “classy” is that we do tend to have convergent issues and convergent interests on a number of issues like intellectual property rights or investments in infrastructure, and we tend to cluster in similar communities. We live and take part in interrelated institutions like nonprofits, higher ed, the media, and the arts.

But there are a few reasons why we don’t cohere well into being a class per se, despite the class-like aspects of us. One of them is that there’s this basic bifurcation within the symbolic professions where one track of people have a lot of prestige, a lot of autonomy, and they have really high pay; and you have other people who make a lot less, they have a lot less autonomy, they’re mostly executing other people’s visions. They have a lot less prestige, but they still have more than normie workers. This is one way in which we consistently misunderstand our own class position. A lot of symbolic capitalists who are, say, adjunct instructors, or similar positions, who are the lower end of this bifurcation, think of themselves as poor. The only reason they can even think of themselves that way is because they really have no understanding of how most of the rest of America lives, of what normie jobs look like, the kinds of income that most Americans make.

But set that to the side. Another thing that argues against us being a class, as my advisor Seamus Khan said, one of the most defining things about us is that we tend to think of ourselves as excellent individuals; we define ourselves in terms of our merit and our individualistic striving. In fact, our institutions select for people who have these kinds of individualistic understandings of themselves and these individualistic narratives. They tell us we’re especially WEIRD [Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic], to use a term from Joe Henrich.

So despite convergent interests, we don’t think of ourselves as a class in a meaningful way. At best, we’re kind of a class in formation, but we’ve not been able to cohere that way because of this deep division that lies within the symbolic professions.

GC: One of the problems the Marxists always had was actually getting the proletariat to conceive of themselves as a class. So this is not new.

MA: Yeah.

GC: The second follow-up question I have is, at the end of the book you spend some time defending the sincerity of the commitment to social justice of the symbolic capitalists. Preparing for the interview, I realized I had enough notes that I might as well publish a book review, and what I wrote there was “Let’s say I tell you I have a ‘sincere’ commitment to sobriety. But every single night you find me out in a bar. At some point, wouldn’t you say that, however often I assert how sincere my commitment is, my actions show that it really isn’t that sincere?”

I know that symbolic capitalists will assert that they’re very tied to their values. But after a certain point, are we entitled to say, well, you’re not putting your money where your mouth is, are you? You seem to defend them against that charge, and I wonder if that defense is fully justified.

MA: What I’m trying to do is push back against two things. One, there’s this thing in the culture wars, this tight focus on hypocrisy. I think hypocrisy is analytically uninteresting, in part because pretty much everyone is a hypocrite. If you believe in something, you’re basically a hypocrite. And there’s a lot of reasons for that. So I don’t think this kind of conversation about hypocrisy and different sides pointing at each other: “You’re a hypocrite!” “No, you’re a hypocrite!”—that’s not a useful way of understanding. Everyone’s a hypocrite to some extent.

GC: Everyone except me!

MA: [Laughs.] I think two things are true about symbolic capitalists. One, just because you believe something sincerely doesn’t mean something is important to you. You can think, “Oh, it’s great if the homeless people are all off the street.” I don’t think that most Americans want homeless people in their neighborhood, and I don’t think they want to see people struggling to survive and things like that. But solving that problem doesn’t mean simply feeling that way. It doesn’t mean that it’s a really big priority for you in your life to fix it.

A related issue is that while it’s true that symbolic capitalists are sincere in their commitments to social justice, that’s not their only sincere commitment. We’re also sincerely committed to being an elite, which is to say, we think that our perspective should count more than the person checking us out at the grocery store, we think we should have a higher standard of living than Walmart workers, and we want our children to reproduce our own class position. This sincere set of beliefs and desires is in tension with the other set of social-justice-oriented beliefs and desires. It’s hard to be an egalitarian social climber, right?

Often when these two sincere beliefs come into conflict, the desire to be an elite ends up winning out, leading us to pursue social justice in largely symbolic ways—or to pursue social justice by trying to expropriate, to take things from others, and assign blame onto others, without making any meaningful sacrifices to how we live our own lives and what our own aspirations are.

I think that’s what’s happening. It’s not that they’re not sincere. It’s that this isn’t their only sincere commitment, and it’s not their top sincere commitment.

The last thing I’ll say about this point is, read Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier. He was looking at what makes socialism unappealing to normies, and he said one of the things that’s really unappealing about socialism is this intense focus on things like automation. There’s this utopian vision: they call it fully automated luxury communism, where no one has to work anymore. They think that’s a paradise. Orwell says that would be hell. It would be miserable because one of the ways that people find community, meaning, and purpose in life is through work. Work isn’t just the way that we pay the bills. There’s this deep human need to be productive, to do things that are valuable and to produce things.

A lot of the socialists say, “You know, under fully automated luxury communism, there’s nothing that would stop you from working. If you want to work, you could go ahead. You could do that.” But the truth, Orwell argued, is even if that were technically a possibility, no one’s going to do it in practice. What they would end up doing is to spend that time trying to fill that hole with drugs, alcohol, and entertaining themselves to death. The fact that most people would do that doesn’t mean that this is what they want. They don’t want to just get drunk and high and entertain themselves to death. But that’s what they would end up doing, because social defaults are strong.

I think this is a powerful point about how people can embrace states of affairs that they detest, or they can fail to live up to the things that they say they value, and that doesn’t necessarily mean that they don’t actually believe those things. It’s just that there’s all sorts of things that frustrate our desires to see a certain type of society or to live a certain way.

GC: Your remarks about that tension remind me of when I was a visiting Ph.D. student at NYU, and I attended two colloquiums. One was Mario Rizzo’s free-market-oriented colloquium, which met in a small, cramped room with kind of crappy tables, with a view of another building and no amenities. And then there was Thomas Nagel’s and Ronald Dworkin’s very egalitarian colloquium, which met in a luxurious room with leatherback chairs and a view out over Washington Square Park, and pitchers of ice water every few seats. I thought, it’s kind of funny that the egalitarians have so much nicer accommodations than the free-market people.

Now, I started to wonder at times—reading the beginning of your book, describing beliefs as self-interested—does anyone actually believe in anything, or is everyone just acting in their self-interest? Was it in your self-interest to write this book, for instance?

MA: It definitely was part of the reason that I wrote it. I have this set of questions that I’m interested in, but part of the reason I wrote and published it with Princeton University Press is because I’m on the tenure track. One of the things that’s interesting about the book is that in some ways it’s a physical embodiment of the things that I talk about. It’s a literal, direct, physical embodiment of a lot of the things that I criticize. For instance, one of the things that the book highlights is the use of educational credentials—and especially credentials from elite schools—to sort out who deserves to be taken seriously, which perspectives are valuable. But this is a book that I targeted at prestigious university presses, and the reason this book was picked up was in no small part because I am affiliated with Columbia University.

If I were a Ph.D. student at the University of Arizona or Stony Brook, even if I sent in the same manuscript, changing absolutely nothing, it’s likely that the book wouldn’t have gotten picked up by anyone, let alone Princeton. There probably wouldn’t have been a competitive auction for the rights, in the same way that before I was at Columbia University, when I was at University of Arizona, I would pitch to places like the New York Times and the Washington Post, and I wouldn’t even get a no; I was below rejection. And then, when I moved to Columbia, I had editors from the New York Times and the Washington Post reaching out to me cold, saying, “Hey, would you like to write something for us?” It wasn’t because I became a much better writer between the time it took to move from Sierra Vista to Manhattan; it’s purely network effects, institutional effects, and the like.

The same is true with respect to race and ethnicity. The book highlights ways that symbolic capitalists leverage their association with marginalized and disadvantaged groups to advance their own interests. But the reality is that part of the reason that this book was published in the form it was is because I’m black. It’s not the case that everyone who’s black gets a Princeton book, but if I weren’t black, if I were white, if I had written the exact same book, especially if I had any hint of conservatism or evangelical Christianity or something like that about me, chances are this book wouldn’t have been published. Or even if I were just a white liberal, chances are this book wouldn’t have been published by this press, certainly not in its current form. Part of why this book was so attractive to a lot of publishers is because I’m black. So the book is itself in many respects a direct embodiment of the things I criticize in the pages, and rather than just pretending that’s not true, I think it’s important to lean into that and wrestle with that contradiction, apply it to myself reflexively.

GC: So in writing the book you not only proposed your thesis, you exemplified that thesis at the same time. Well done! Very meta of you.

MA: I’m a sociologist of knowledge, so I can’t help getting super meta at all times.

GC: The book talks about racialized inequalities at a number of places. Are you familiar with Gregory Clark’s The Son Also Rises? It came out a decade or so ago.

MA: The name is familiar . . .

GC: He was trying to show that there were different degrees of social mobility in different societies and wound up discovering that social mobility was mostly constant across societies and that elite status tended to persist for many generations. He went back into the Domesday Book and found that some of the same names are still prominent at Cambridge and Oxford. It is very well researched.

So when we look at the racial characteristics of the elite in the U.S., how much of this could be explained simply by the fact that two hundred years ago, essentially if you were elite in the U.S., you were white? And this elite status persists: what we see now is simply this persistence. Now we could try to pull this apart from race itself, for instance by seeing how likely are the descendants of a poor white family and a poor black family to have attained elite status.

MA: Yeah.

GC: So what do you think about how much of this is any current racial issue aside from the fact that all the elites were white a few generations ago, and so naturally today more of them are?

MA: I wrote about this a little bit. For the Heterodox Academy, I had an essay looking at the composition of the professoriate along the lines of race and gender. This is one of the things that I argued, that one of the big obstacles to diversifying the professoriate is that these are lifetime appointments, and society changes a lot faster than there’s turnover in terms of the lifespan of people who work in these professions. So even in the absence of formal discrimination, you can see this pattern where the professoriate will be unrepresentative, and actually in some respects increasingly unrepresentative of society as a whole, even in the absence of formal discrimination. In fact, there is a great paper that was published in the National Bureau of Economic Research recently. It showed that even in a world where there was no Jim Crow, where there was no segregation, where there was none of that, you would expect to see significant black and white income gaps for some of these same reasons. An element of these disparities is a result of this kind of path dependency and elite reproduction. But one of the things that’s interesting is that if you look at the symbolic professions, and if you look at some of these macrosocial trends, part of what’s happening is there’s this, as Richard Reeves called it, “opportunity hoarding” by people who are elites—to protect and preserve their elite status, to create glass floors for their children, to make sure their children reproduce their status—in ways that undermine things like social mobility. You see this cartel-like behavior.

One of the things I show in the book is that if the knowledge economy followed traditional supply and demand, one thing that you would expect to see is a demand for a lot of service jobs. It’s hard to even find enough people to work those jobs, and for a lot of knowledge economy jobs, there’s this huge overproduction. Take higher ed, for instance: there’s this huge glut of people who want to be professors and not nearly enough jobs. If traditional supply and demand laws worked here, what you would expect to see is that the pay for professors would be going down, and the pay of service workers would be going up radically—especially relative to one another.

Instead, what you see is that the gap between professors and service workers is growing bigger. Professors are doing better and better relative to service workers, whose wages are relatively stagnant compared to the knowledge economy workers. So this isn’t just the market and path dependency. This is caused in some respects by cartel-like behaviors and opportunity hoarding and other things that prevent the kind of churn among the elites that would be necessary to allow some of these problems to mitigate themselves over time. Instead of getting better over time, they in some cases grow worse because of active choices that we make today, not carryovers from Jim Crow, not carryovers from slavery, not carryovers from racial redlining, but because of decisions that we make today that exacerbate various forms of inequality, and, in fact, especially in a lot of the professions that are hyperwoke. They tend to be some of the places where these disparities are most pronounced.

In terms of race and ethnicity, the symbolic professions are some of the most parochial workplaces, as I show in some data tables for the whole country, and even in terms of things like gender. Although a lot of these professions have been feminizing at a rapid rate, gender disparities between men and women are actually greater in the symbolic professions than they are in society at large.

I think part of it is the story of path dependency. You have the elites who looked one way, and then—even in a situation where things were genuinely open and procedurally fair—you would expect a degree of the initial distribution to persist for a while. So part of it is that. But part of it is definitely that it’s choices that we’re making today that exacerbate and perpetuate some of these unfortunate dynamics.

GC: A certain amount of that path dependency is going to arise precisely from the fact that elites have power to make sure their own kids attain elite status. Right?

MA: This is my point: it’s not a situation where you’re talking about some kind of genuinely open, procedurally fair thing where it’s just some people have advantages, they go to better schools, they have healthier diets, they live in better neighborhoods, and things like that. Those are examples of a kind of an elite path dependency. A whole bunch of other people don’t have those advantages, so you would expect to see certain inequalities reproduce themselves even in the absence of formal discrimination or cartel behavior or anything like that. But a lot of these disparities that I point in the book are not just that. They’re clearly the result of cartel-like behavior, active exclusion, and active decisions that people are making today. So, for instance, in some cities racial segregation is worse today than it was in the 1980s. You can’t explain why things are worse today than they were in the 1980s because of racial redlining, or Jim Crow, or anything like that, right? That can only be explained by choices that we make today—that took a trajectory that was going one way and turned it another way. A lot of these problems are actually the result of active decisions we’re making here and now, not just leftovers of the past.

GC: I recall there was a proposal to merge one of the school districts in elite Brooklyn Heights that would make it incorporate the housing projects on the other side of Tillary Street. The residents of Brooklyn Heights exploded.

MA: Yes, they did.

GC: They were furious about this. So the racial aspect is interesting. But if this had been a bunch of poor rural whites [added to the schools], they probably would have been just as upset. And if the neighborhood had a bunch of wealthy black doctors and lawyers in the newly included neighborhood, I think they wouldn’t have minded at all.

MA: Class is important. One of the cultural contradictions the book highlights is that a lot of times we mobilize social-justice discourse in ways that actually help us justify inequalities, that help us explain why people who are losing and suffering under our prevailing order deserve their suffering, deserve to be marginalized.

For example, a lot of the narratives we tell about white privilege: We tell this goofy story where every white person has the same racial privilege. Someone who is a checkout counter clerk who lives in Appalachia has the same white privilege as a professional who lives in San Francisco, and as I show in the book, it’s just not the case that everyone benefits in the same way from their race, even if they share the same race. That’s just false. But setting that aside, when you look at what teaching people about white privilege does, what effect does it actually have on people? It turns out there’s a lot of empirical research on this, that teaching people about white privilege doesn’t cause them to think about non-whites any differently. It doesn’t cause them to behave any differently towards non-whites. The main effect is that it causes them to look at poor whites and think that those people must really deserve their plight. They were born on third base. They were born white. They had all this privilege, and look at them: they’re still poor!

This is a very convenient narrative for elites to hold because a plurality of poor people in the United States are white. You tell a story that allows you to write off the suffering of the lion’s share of poor people in America—to say, “Not only do we not have to worry about allocating anything to them because they would just waste it, they were born with all this privilege, and what do they do with it?” That then also allows us to look at their suffering and think, “Actually, in fact, maybe they have more than they deserve. Maybe they should have less than they have. We want to take from the whites, right?”

We tell these kinds of narratives that allow us to point at the people who are suffering and losing and falling behind in the prevailing order to justify why they deserve their suffering, why they deserve their marginalization, why we don’t have to take their concerns seriously. These narratives about white privilege seem egalitarian, seem social-justice-oriented. But in practice, when you look at how they’re actually mobilized by elites in their social life, what they end up doing in reality is helping us justify inequalities.

GC: We have to take from them until they learn to stop voting for Trump.

MA: We’re going to have to start taking from a lot of blacks and Hispanics, too. In fact, that’s been a big story over the last decade, not just the last election.

GC: This next point may be purely an artifact of your publisher’s requirements. But when John Gray and I were talking [Modern Age, Winter 2024], we brought up how so much social-justice activity results in an empty gesture and rather than actually fixing a problem, I said, it actually covers up for the fact that the problem is not being fixed . . .

MA: Yes.

GC: . . . and does nothing substantive. And John said, “No, I think it’s worse than doing nothing. It takes the energy that could go into fixing the problems and instead renames something.” So the homeless people are now “unhoused.” Don’t you feel better in that cardboard box now that you’re unhoused instead of homeless? But throughout your book, “black” is spelled with a capital B.

MA: Yes.

GC: Is this the kind of empty gesture we should be resisting? Because I don’t see that that’s actually improved the lot of people who are suffering in a terrible housing project. They’re still in the terrible projects. But we now spell their race with a capital B.

MA: Absolutely. That was a thing that the publisher did. In my initial manuscript, I didn’t capitalize the B.

GC: I thought that might be it.

MA: That’s their standard practice. But, you know, I didn’t fight about it precisely for the reason that there’s actually nothing at stake here, so if they want to capitalize it, okay. If I insisted on keeping it lowercase, what would that accomplish? Nothing. I was more worried about more important, substantive things.

GC: Yes, it is a minor point, but to that extent where, if you go along, if someone says to me, “Don’t call them homeless. They’re unhoused!” and I go along with it, am I agreeing to pretend that there’s a substantive change here?

MA: In the case of “unhoused” and “homeless,” there is a problem. I would push back about that, in part because there’s a lot of research that shows euphemisms make people more comfortable with adverse states of affairs. If you call them “unhoused” instead of “homeless,” what you’re doing is obscuring the brutality of the conditions that they’re living under. It makes it easier for people to tolerate that kind of thing.

If they wanted to replace a bunch of stuff in the book with euphemisms, I would have probably pushed back against that. That would actually cut against the point of the book. But a stylistic point, like if you capitalize or lowercase something, that’s the kind of thing that I don’t care about.

GC: Like I said, that’s a very minor point that just struck me. I do appreciate your taking the time to talk with me.

MA: It was a lot of fun.

GC: Thank you.

MA: And thank you.