Who among us retains sentimental views about the late 1960s?

Who, really, still clings to the fiction of free love, considers folk music to be the summit of musical expression, gets misty-eyed about flower children, or looks back on the Vietnam War as unquestionably and uncomplicatedly bad? Evidently there remains an aging, graying remnant of nostalgists for the cultural affectations of that decade, but I would have never guessed that filmmaker Paul Schrader was among their ranks.

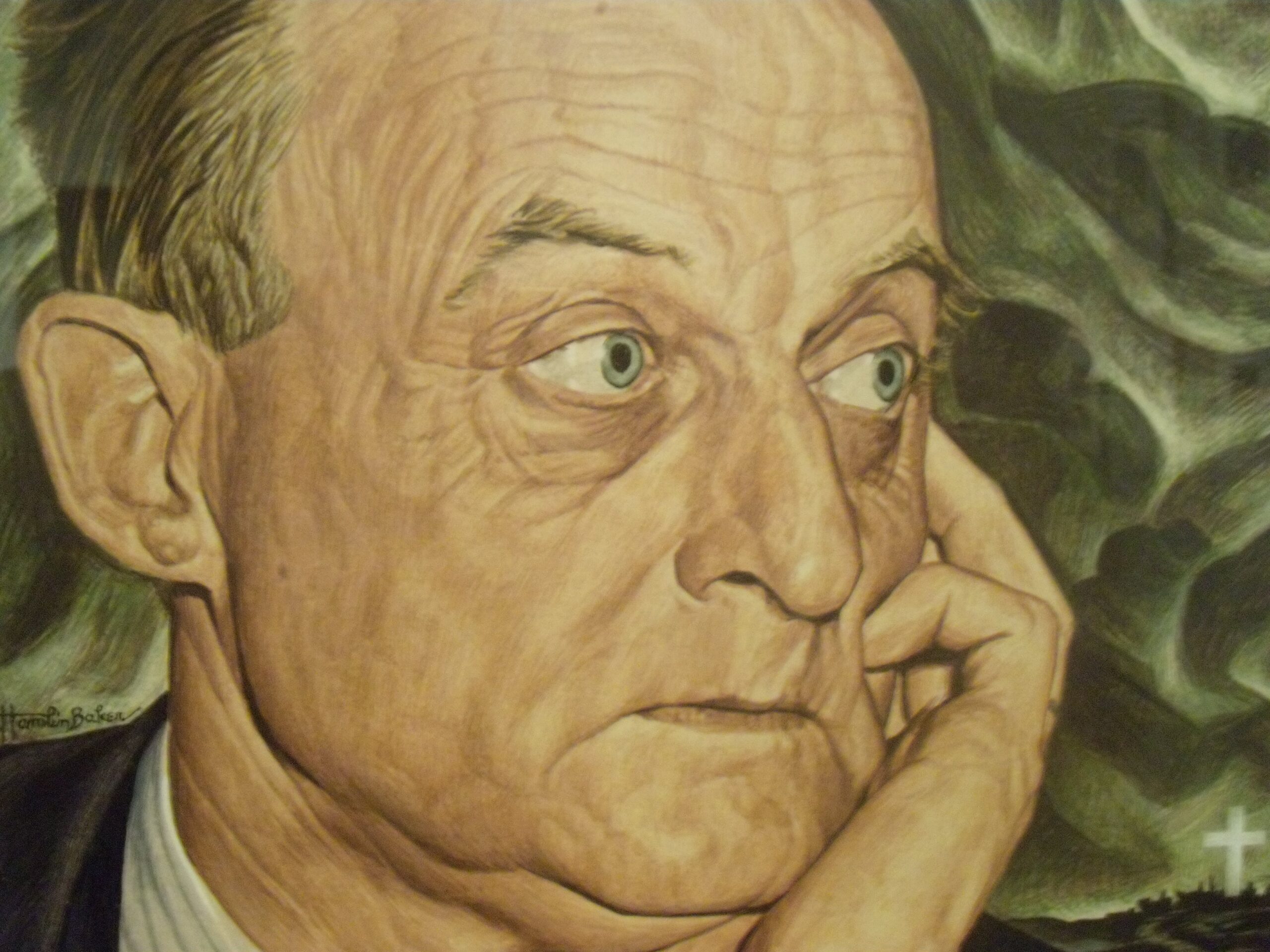

Schrader, who was born in 1946 in Grand Rapids, Michigan, belongs to the generation that fell hard for the clichés of the late Sixties, but, owing to the unique circumstances of his upbringing, he was better equipped than some to resist it. Shielded from popular culture by the Dutch Calvinist faith of his parents, Schrader has generally characterized his subsequent professional embrace of film as one of defiance—“I fell in love with movies because they were forbidden,” he said in the book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls—but his own cinematic tastes were arguably informed by, rather than opposed to, his religious training.

At a time when many young cinephiles were operating under the influence of mainstream artists such as Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, and even Chuck Jones, Schrader attended to the work of theologically oriented international filmmakers such as Robert Bresson, Carl Theodor Dreyer, and Yasujirō Ozu, about whom he wrote a book, 1972’s well-regarded Transcendental Style in Film. By the time Schrader began writing and directing, he had to negotiate the competing interests of his spiritual inclinations and studios’ commercial obligations, but, every so often, he struck the proper balance: Blue Collar (1978), Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), Light of Day (1987), Affliction (1997), and, more recently, First Reformed (2017) were serious films that, for better or worse, seemed to emanate from a directorial personality unpolluted by the secular, materialistic industry in which he toiled.

How shocking it is, then, to find Schrader responsible for the hash that is Oh, Canada, which the director adapted from Russell Banks’s novel Foregone. As a film critic, Schrader once assailed the dumb clichés of the prototypical hippie-dropout extravaganza Easy Rider (1969). “Easy Rider’s superficial characterizations and slick insights stem from the same soft-headed mentality which produced such anathema ‘liberal’ films as Elia Kazan’s Gentleman’s Agreement and Stanley Kramer’s Defiant Ones,” Schrader wrote in the Los Angeles Free Press. “But because liberals and leftists of all varieties so desperately need the strong statement Easy Rider makes, they are willing to overlook the film’s shallow, conventional method of argument.”

Amazingly, Schrader has produced something like Easy Rider Gets Cancer—except, in fairness, the lead character more closely resembles an elderly, infirm version of Jack Nicholson’s Robert Dupea in Five Easy Pieces than the motorcycle-riding bandits of Easy Rider. Like Dupea, Leo Fife in Oh, Canada specializes in desertion. By the time he makes a name for himself as a nonfiction filmmaker in Canada, the Massachusetts-born Fife has left behind nearly everything in his life worth keeping. He has forsaken the counsel of his family, jettisoned his first wife and child, abandoned his second wife and child, and finally renounced his country by setting up residence in Canada to dodge service in Vietnam.

In the movie, Richard Gere plays Fife in his present-day terminally ill state: Rendered nearly bald, mostly wheelchair-bound, and understandably (though repetitively) cranky by his cancer diagnosis, Fife has been roped into participating in an interview for a documentary on his life. The documentary is the brainchild of Fife’s former students Malcolm (Michael Imperioli) and Diana (Victoria Hill), who have embarked on the project in the most pretentious manner imaginable. The duo seems to regard Fife as a Canadian cultural institution, which is a tough sell given that the examples we see from Fife’s own work—social-issue-style documentaries with titles like The Shame of Canada and Slaughter on the Ice—suggest nothing more rarefied than what we might encounter on an episode of Frontline.

For his part, Fife seems to regard his participation in the documentary less as a chance to burnish his reputation than to bring into the open his perceived faults. Insisting on the presence of his third and current wife Emma (Uma Thurman), Fife characterizes the narration that follows—largely uninterrupted by the increasingly superfluous Malcolm and Diana—as a kind of confession. He recounts his history of romantic and familial abandonment, but to call Fife’s monologue a confession implies guilt, and guilt implies judgment. Alas, there is no judgment on offer here. Schrader seems to have lost the last traces of his Calvinist harshness.

As shown in flashbacks, the late-Sixties-era Fife (Jacob Elordi) is seldom presented as being on the wrong side of any argument. For example, the breaking point in Fife’s second marriage to Alicia (Kristine Froseth) turns out to be the invitation by her rich father to slide into the lucrative family business—hardly an unreasonable or insulting invitation, especially since the offer comes with the understanding that Fife, who at the time fancies himself a writer, will have plenty of time for his art. Yet Schrader has a way of making the grown-ups in these scenes sound just like the “plastics” guy in that famous scene from The Graduate. Fife is rendered as the typical angry young man and therefore is meant to be thoroughly empathetic in his alienation. “I just don’t feel comfortable with them,” Fife says, lamely, of his wife’s well-to-do family.

Throughout the film, Fife appears to be no more than an adequate intellect, but his proclamations are taken entirely too seriously by the suddenly gullible Schrader. Young Fife denounces the novel From Here to Eternity in the same tired terms that Truman Capote once lambasted Jack Kerouac (“That’s not writing, that’s typing”), while mature Fife is seen convening a filmmaking class in which the central text is Susan Sontag’s On Photography. As we all know, the quickest way to establish a movie character’s intelligence is for him to invoke a “public intellectual” like Sontag. (That’s why Woody Allen included her among the talking heads in his mockumentary Zelig—she embodied the sort of cerebral, erudite-sounding voice that would impress the middlebrow viewer.)

Oh, Canada becomes interminable long before it clarifies its central point, which seems to be that the motivation for Fife’s exile in Canada was not just his eagerness to avoid the draft but his restlessness and frustration with family life. Lurking here somewhere is the start of a thoughtful idea, but the film makes a hash of this, too. Implicit in the chastisement of Fife for going to Canada for reasons other than dodging the draft is the assumption that dodging the draft is a perfectly worthwhile goal (rather than a crass and cowardly one). The virtuousness of our hero may be called into question, then, but the virtuousness of liberalism itself never is. The film endorses Fife’s view of Canada and (earlier) Cuba as Edenic destinations—anywhere but that awful country that birthed him.

The film eventually descends into a catalogue of cringe-inducing clichés, up to and including the presence of Thurman in a second role in the flashback sequences. She fleetingly plays a spaced-out hippie, and, wearing a headband and donning a peace symbol necklace, she resembles an aging cast member from Godspell. The film reaches what might be considered peak late-Sixties nostalgia when we see clips from Fife’s first documentary: shots of U.S. government airplanes dusting fields with Agent Orange are blended together with psychedelic editing.

I would like to say that Paul Schrader is too smart for all of this, but perhaps it is more accurate to say that he once was too smart. Years ago, he had punctured the myths of Easy Rider; these days, he is happy to perpetuate a senescent version of them with a straight face.