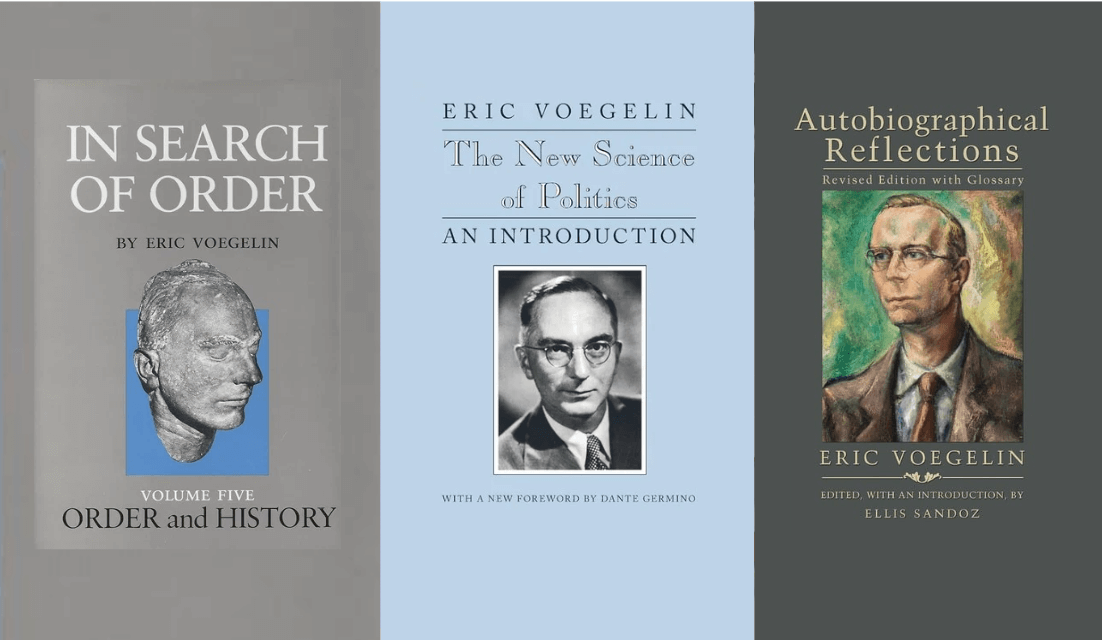

A seminal political theorist, Eric Voegelin wrote on a variety of topics, including the history of political ideas, the philosophy of order and history, and the philosophy of consciousness. Voegelin’s five-volume Order and History (1956) and his New Science of Politics (1952) are among his best-known works.

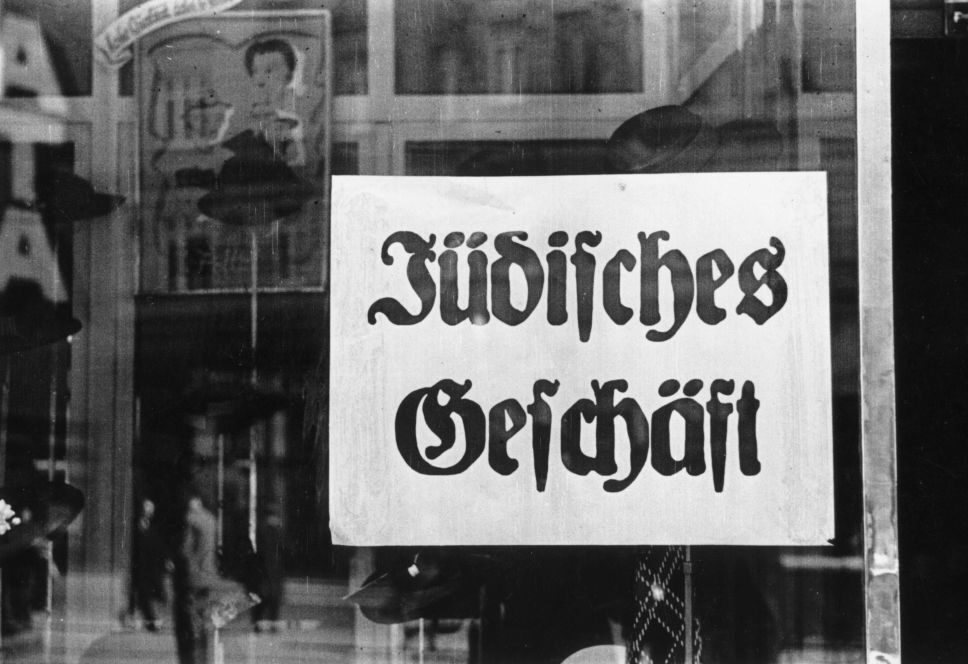

Voegelin was born in Cologne, Germany, and moved to Vienna, Austria, at the age of nine. Receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Vienna in 1922, he was investigated by the Nazis after the Anschluss and escaped to the United States in 1938 via Switzerland. He became an American citizen in 1944 and held academic appointments at Harvard, Bennington College, and the University of Alabama before accepting a position at Louisiana State University, where he remained for sixteen years. In 1958 he was named the director of the Institute for Political Science at the University of Munich, but he returned to the United States in 1969 as a Henry Salvatori Distinguished Scholar at the Hoover Institute.

Voegelin’s connection to conservatism is ambivalent. He insisted on rejecting all ideologies and “ismic” constructions, including conservatism. He classified conservatism as a “secondary ideology,” by which he meant that it was created in reaction to radical ideologies like National Socialism, Marxism, even liberal progressivism. Radical ideologies destroy traditions, customs, and laws that conservatives believe are vital to the good society. To counteract the destructive effects of radical and revolutionary movements, conservatives try to preserve the wisdom of the past by defending tradition as if it were the same as truth itself. In doing so, Voegelin argued, truth becomes reified and separated from its engendering experience.

Voegelin considered the moral skeptic David Hume to be a representative of conservatism, but he had very little to say about Edmund Burke. Hume he criticized for being philosophically shallow because he relied on tradition and common sense. To gain philosophical insight, argued Voegelin, it is necessary to go beyond mere tradition and penetrate to the core experiences of order by recalling them to consciousness. Following Plato, Voegelin called this process of recollection anamnesis. He also disparaged the contribution of Cicero to political theory in his posthumously published History of Political Ideas (1997). Cicero, an important figure to conservatives, was criticized by Voegelin for thinking too highly of Roman institutions—for addressing the complex philosophical problems associated with political order by professing the majesty of Rome. Cicero’s political theory is too concrete. Plato, in Voegelin’s estimation, was a far superior thinker because he understood that true philosophers are more satisfied by questions than institutional answers. Political institutions always fall short of representing the true, the good, and the beautiful. They are not the source of philosophical wisdom. And philosophers ought never to be satisfied with particular representations of the good. The philosophical quest ends only in death.

Many aspects of Voegelin’s political theory are consistent with conservatism, however. He influenced greatly such conservative thinkers as Russell Kirk, Gerhart Niemeyer, and Ellis Sandoz. (Voegelin’s influence on Kirk is especially evident in Kirk’s Enemies of the Permanent Things [1969].) Conservatives have found Voegelin’s work appealing for several reasons. First, he was a severe critic of left-wing ideologies and political movements. He was especially critical of progressivism, positivism, Marxism, and liberalism. Voegelin also contributed to the recrudescence of scholarship in the classical and Judeo-Christian philosophical traditions, drawing on the political theory of thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, and Thomas Aquinas. Finally, Voegelin made insightful theoretical connections between liberalism and totalitarianism.

Nevertheless, Voegelin has been criticized by some Christian conservatives for his treatment of Christianity. They claim that Voegelin did not appreciate fully the contribution of Christianity to history and Western civilization. They point to the fact that in the fourth volume of Order and History (The Ecumenic Age), Voegelin connected St. Paul and other Christian figures to modern gnosticism and modern political movements. These Christian critics charge that Voegelin seems to have underestimated the positive contributions of Christianity. Other conservatives have criticized Voegelin’s conception of transcendence for being too abstract and distant from politics. Like Plato, Voegelin tended to recoil from concrete representations of the good in political life.

Voegelin was a fierce and consistent opponent of totalitarianism in all its forms. In 1933, he published two books on the race problem (Race and State [English translation, 1997] and The History of the Race Idea [English translation, 1998]) and his opposition to communism is evident in many of his books and essays. Voegelin’s review of Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) reveals his disdain for totalitarianism as well as his impatience with critics of the left and right who failed to identify the spiritual causes of totalitarianism and the philosophical roots it shared with liberalism. His lectures on Hitler at the University of Munich in 1964, published in English as Hitler and the Germans (1999), are representative of this aspect of his work.

The core of Voegelin’s political theory is the insight that ideas and language symbols are secondary to historical experience. Human understanding of reality develops from experience with transcendence. Transcendent experience is articulated by spiritually sensitive individuals (e.g., Homer, Plato, Augustine) who create language symbols to convey the meaning of reality. These symbols make it possible for others to imaginatively relive the experiences of order and in turn order their souls. In this way historical experience becomes a living force that is capable of resisting disorder. The common ordering element in all historical experience with transcendence is the parousia or the “indelible presence of the divine.” In different civilizations at different times in history, a common reality is discovered that is recognizable to those who are capable of achieving a similar level of transcendent consciousness. Restoring these experiences and keeping them vibrant was Voegelin’s life project.

The crisis of Western civilization was caused by the loss of consciousness of these experiences. Consequently, the restoration of Western political and social order depended on the reawaking of Western consciousness to the truth of existence embodied in the formative historical experiences of Western civilization. Voegelin insisted that dogma and doctrine obscure the truth of reality by reifying it. Dogmatizing truth obscures reality by separating experience and symbols. Voegelin believed that the modern crisis was due in large part to the fact that the symbols of transcendence had become obscure because of ideological doctrinization.

Voegelin determined that human understanding of truth varied in terms of its “compactness” or “differentiation.” Advances or differentiations, however, do not guarantee parallel progress in political and social order. In fact, Voegelin believed that differentiation can have a socially and politically destabilizing affect.

Further Reading

Barry Cooper, Eric Voegelin and the Foundations of Modern Political Science

Michael P. Federici, Eric Voegelin: The Restoration of Order

Ted McAllister, Revolt against Modernity: Leo Strauss, Eric Voegelin, and the Search for a Postliberal Order

Eric Voegelin, Autobiographical Reflections

Eric Voegelin, Science, Politics and Gnosticism

This entry was originally published in American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia, p. 894.