Sir Ridley Scott is on a losing streak. Last year’s Napoleon fell badly flat. This year’s equally hyped sequel to his sword-and-sandals masterpiece, Gladiator, is faring little better. Gladiator II is not a particularly good movie. It suffers from a surfeit of greasy CGI effects—a sad departure from the original’s preponderance of physical effects. The script is tinny, a world removed from its predecessor’s collection of unforgettable one-liners. The actors are strangely inert, exempting the delightful scenery-chewing of Denzel Washington, a consummate professional—he, at least, is going to give the people a good show. And it’s oddly unoriginal, particularly if one is to believe the reports that Scott has been ruminating on this sequel since the release of the first installment; at its best, it is almost a beat-for-beat reenactment of the original film.

But all of that is itself interesting. Classical historical epics and their low-rent imitations were box-office staples in the 1950s through the ’70s. They were a way for Westerners, particularly Americans, to speak to themselves about their culture’s own internal questions: the meaning of political freedom (Spartacus); the role of Christianity in public life (Quo Vadis, Ben-Hur, The Robe); democracy and imperialism (The 300 Spartans). This is an inevitably American tic—our togate statues of the Fathers, the turgid Latin tags on our currency, the Cheesecake Factory monumentalism of our capital city (the layout of which, it is strangely unremarked, is visibly based on the Campus Martius in Rome itself).

The original Gladiator, which was already a bit old-fashioned at its release in 2000, fit perfectly into this tradition. The kernel of the far-fetched plot is that Marcus Aurelius, disgusted with Rome’s political repression and endless wars of expansion, would like to entrust his powers to the general Maximus for the purpose of restoring republican government. Aurelius’ son, Commodus, does not care for this idea, kills his pop, tries to have Maximus executed, and proceeds to ransack the fisc to fund an endless series of public entertainments.

To recapture the feeling of this film, it is perhaps necessary to bring to mind the public life at the turn of the millennium, an almost impossibly different time. Pat Buchanan’s campaign book, A Republic, Not an Empire, came out in 1999, just before his turn at the top of the Reform Party ticket. NATO was expanding eastward. The son of a former president was running for the White House on a “status quo with fewer taxes” platform. The Balanced Budget Amendment was still a live political option. Fifteen years after the publication of Amusing Ourselves to Death and Tipper Gore’s crusade against rap music, Americans still had the sense that perhaps there was something wrong with popular culture and the TV, that perhaps the occupants of the entertainment industry’s commanding heights did not in fact have their best interests at heart. Evangelical Christians were on the ascent, and secularist atheists were becoming more strident in response. Of course a big, bloody historical epic about Rome and the nature of political life was the movie of the year. You’d have thought it was the beginning of a renaissance for the genre.

But then something happened—specifically, I think, 9/11 and the Global War on Terror. The historical epic with its classic characteristic traits again disappeared from the big screen. Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ, released in 2004, is conspicuously uninterested in the Roman aspects of first-century Judaea, let alone big questions about government or culture. Zack Snyder’s 2006 movie 300 is more or less an explicit, gleeful repudiation of the historical epic genre. Religion and political government are derided; Gerard Butler’s Leonidas does not deliver ponderous speeches, but gleefully prances about hollering and killing diplomatic personnel; in place of the family-friendly gallantry of Gladiator, 300 had what is (I believe) the world’s first CGI-enhanced sex scene in a mainstream motion picture. Instead of the great problem being some disorder within the Spartan or Greek body politic, it is a horde of Middle Easterners who hate us for our freedoms. In short, a paroxysm of fascistic Bush-era propaganda.

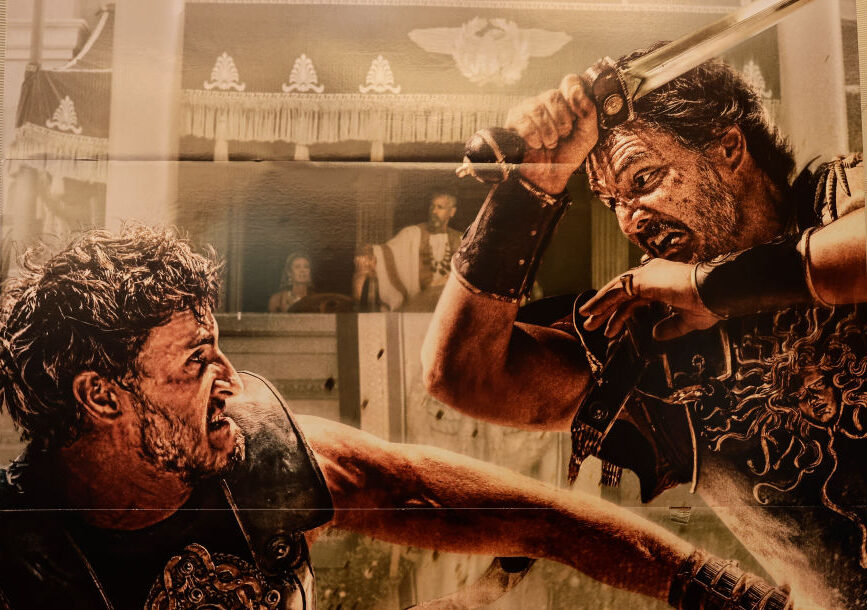

Which is why it’s intriguing that the old-fashioned article is now back in the form of Gladiator II, albeit clumsily executed. The film opens with a Roman assault on a North African city where a motley resistance to imperial rule is making its last stand. Paul Mescal’s unexpressive Hanno watches his warrior-wife Arishat die on the ramparts, is himself wounded, and is enslaved and sold into gladiatorial bondage. Washington’s Macrinus, who has made his fortune supplying weapons to the Roman legions, recognizes his talent and takes him to the big show in Rome. There, Hanno gets caught up in byzantine and frankly badly written schemes on the one hand to restore the republic—it is not clear why this did not happen after the action of Gladiator—and on the other to raise Macrinus to the purple.

It’s pretty shoddy stuff, but it’s there—the big ideas! The internal contradictions! Surely it is no accident that, after a hiatus of a quarter century, the story reopens with the apparently senseless invasion of a remote desert stronghold, or that it features a military–industrial contractor with his eyes set on yet more political power. Nor do the peculiar turmoils of these latter years over race and national identity go without oblique comment. Alexander Karim’s Ravi, a gladiator-turned-doctor, notes that he is married to a Briton with the remark, “We’re Romans now.” (It defies tasteful comment that, apparently even in ancient Rome, the doctors are of Indian extraction.) The film’s explicit central question is whether “the dream of Rome,” explicitly identified with equal justice under the law, is real or Rome is the Nietzschean jungle that Macrinus insists it is. Heady stuff, and topical. Too bad it’s not very well done.

It’s pretty shoddy stuff, but it’s there—the big ideas! The internal contradictions!

The movie’s apparent answer to that central question is not terribly encouraging, either. Gladiator II ends with the suggestion that the Senate and People are restored to power—but so does Gladiator, which is set a mere sixteen years before. This is hardly strong narrative assurance. The source material for Gladiator II, loosely, is found among the lost years of the third century and the febrile mendacity of the Historia Augusta, in whose pages fantasies of republican restoration occasionally crop up; yet they remain fantasies. Especially in the absence of some explicit, alternative history at the end of this movie, a viewer who knows what really happened finds it crowding in to fill the blank spaces. If Scott is in fact returning to a preoccupation with the nature of the American order, his prognosis is pretty grim.

Gibbon reports a strange episode from the reign of Decius in the middle of the third century, not so long after the time in which Scott sets his fable. The emperor was disturbed by the decline of the Roman commonwealth and decided to revive an ancient legal form to arrest its causes:

At the same time when Decius was struggling with the violence of the tempest, his mind, calm and deliberate amidst the tumult of war, investigated the more general causes that, since the age of the Antonines, had so impetuously urged the decline of the Roman greatness. He soon discovered that it was impossible to replace that greatness on a permanent basis without restoring public virtue, ancient principles and manners, and the oppressed majesty of the laws. To execute this noble but arduous design, he first resolved to revive the obsolete office of censor; an office which, as long as it had subsisted in its pristine integrity, had so much contributed to the perpetuity of the state.

An inconvenient invasion of Goths causes him to call off the plan (and cuts short his life), which Gibbon, that canny old skeptic, emphatically thinks was for the best:

A censor may maintain, he can never restore, the morals of a state. It is impossible for such a magistrate to exert his authority with benefit, or even with effect, unless he is supported by a quick sense of honour and virtue in the minds of the people, by a decent reverence for the public opinion, and by a train of useful prejudices combating on the side of national manners. In a period when these principles are annihilated, the censorial jurisdiction must either sink into empty pageantry, or be converted into a partial instrument of vexatious oppression. It was easier to vanquish the Goths than to eradicate the public vices, yet even in the first of these enterprises Decius lost his army and his life.

Perhaps a return to older, better traditions is too tall an order; perhaps you can’t go back to the censor, to republican government, to making historical epics in 2024. But it is nice to see someone try. And the fact that someone is trying may be a small, soft sign that at least one of the darker discursive chapters of the American story is behind us.