“Cut out the middleman”: this common idiom reveals the uncomfortable position of the go-between in capitalist economies. The middleman’s position in the market is all too often misunderstood.

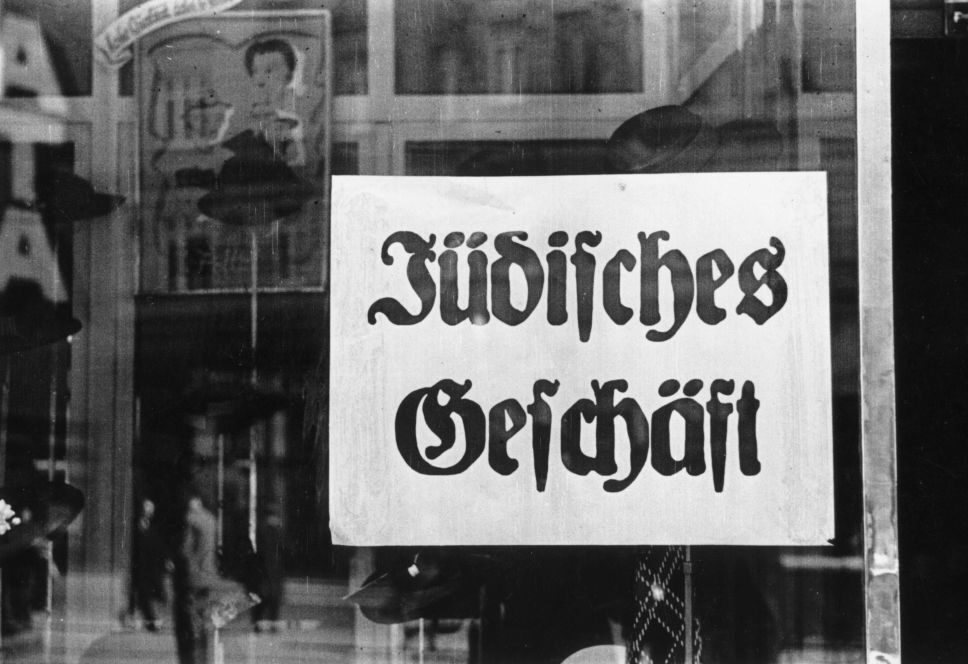

That’s particularly the case when he comes from a minority group. Throughout history, “middleman minorities” have been associated with occupations such as retailers and moneylenders, not directly producing goods but performing a vital role in connecting producers to consumers. And yet when these minorities achieve modest prosperity, they are often met with hostility. Jewish communities in the West are notable examples: despite starting with nothing and earning their success, they historically have been wrongly accused of maintaining a stranglehold on economic resources, a myth that continues to fuel antisemitism today.

Jews are not alone in this unenviable position. In an article titled “Is Antisemitism Generic?” the economist Thomas Sowell argues that such anti-Jewish attitudes reflect a broader pattern of persecution toward “middleman minorities.” Other groups that fall into this category include the Chinese overseas, Indians in Southeast Asia, and the Igbo people in Nigeria.

The rise of globalized trade and digital economies has only expanded the role of middleman minorities as they have moved beyond traditional industries like retail and exerted influence in global tech and e-commerce. After its forced expulsion from Malaysia, for example, Singapore transformed from a small island into Southeast Asia’s financial center and one of the world’s most developed countries in just thirty years. And in the United States, Silicon Valley’s South Asian diaspora has significantly contributed to advances in technology.

And yet the middleman minority, and his role in the economy, is as poorly understood as ever. In fact, this success comes in part from the suspicion with which they are often viewed. In his book Migrations and Cultures, Sowell argues that the “middleman minorities” were united by society’s reaction to them, as many individuals within these minorities may not hold middleman jobs but are nonetheless treated similarly by the majority population. While middleman minorities are not confined to a single race or culture, all have been persecuted for having something in common: what Sowell describes as the human capital of “experience and knowledge used in economic activity.”

So why are they seen as suspect if their contributions are so useful? Sowell notes that fewer people reach the upper echelons of middleman professions, which require greater education or sophistication, than the lower levels. Yet, what he calls “modest prosperity” among middleman minorities provokes more societal animosity than the wealth enjoyed by other groups, such as the nobility or entertainers. There is a common perception of middleman minorities as parasitic because the occupations they are associated with don’t produce goods directly, a view further intensified by their “racial or cultural differences” from the majority group.

During periods of heightened intergroup tensions, this can lead to mob violence. The Holocaust is an example of a culmination of centuries of resentment toward the Jewish people in Europe. In the May 1998 riots in Indonesia, anti-Chinese sentiment at the end of the New Order regime fueled mass lootings and fires targeting Chinese Indonesians, and during the 1966 anti-Igbo pogrom, mobs killed 8,000 to 30,000 Igbos en masse.

Capitalism itself often gets blamed for this persecution. But that view is mistaken. Sowell’s fellow Chicago School economist Milton Friedman, in a section about discrimination in his book Capitalism and Freedom, discusses how Jews, who became financiers and moneylenders, persevered through the Middle Ages as a result of the market sector, allowing them to operate despite persecution. While minorities are often the most vocal critics of capitalism, Friedman argues that capitalism is frequently misunderstood as the force behind “the residual restrictions” they face, rather than the force that minimized those restrictions.

How, then, does the invisible hand of the market benefit middleman minorities? Is a free-market approach superior to government policies that directly target them? Economic efficiency suggests that any preferences beyond productive efficiency will disadvantage “businessmen or entrepreneurs” by narrowing their choices, thereby raising their costs. Those who avoid discrimination based on ethnicity or race when making purchases will, in turn, benefit from lower prices. This principle applies not only to middleman minorities like European Jews during the Middle Ages and beyond but also to racial minorities such as African American salespeople during the Jim Crow era.

According to Sowell, a “special intense violence” has been directed at middleman minorities because they perform economic roles that are “misunderstood and condemned” by the majority population. This is evident in the prevalence of minority-focused conspiracy theories, such as the false claim that Jews control the banking industry. A similar dynamic is seen in Malaysia, where demagogues exploit reports such as the Forbes list of billionaires, which shows that in 2024 86 percent of the country’s wealth is held by Chinese Malaysians.

The economist Geoffrey Williams attributes this statistic to the country’s New Economic Policy and Bumiputera affirmative action, which disadvantaged the Chinese community by limiting access to certain opportunities in favor of the Bumiputera majority. These policies pushed them into entrepreneurial roles, particularly in middleman professions like trade, and further reinforced perceptions of “clannishness.” Thus, capitalism’s private economy provided a path for the Chinese Malaysian population to accumulate wealth despite the structural disadvantages imposed by such policies.

Middleman minorities have emerged for other reasons, as well. Sowell highlights the case of Jewish credit lenders in Argentina, arguing that “local middlemen” from the majority group, even when attempting to emulate their Jewish counterparts, often struggle to compete.

The bottom line is that capitalism is not only not to blame but actually can be a boon. Throughout history, it has often been only within capitalist markets that middleman minorities could sustain themselves, specializing in tasks and accumulating wealth despite government interference. Middleman minorities possess a long expertise that may be carried over by generations, and are willing to endure initial economic modesty, offsetting smaller profit margins by building a larger consumer base.

The term “middleman minorities” should be understood in more than just the economic sense; it extends into the social and political spheres, as well. In Southeast Asia, the rise of ethnic Chinese people as intermediaries in international trade reflects the majority population’s reluctance for direct interaction with foreign parties who may not speak the same language. Capitalism, in this sense, allows minorities to achieve upward social mobility by filling gaps left by the majority.

The role of the middleman minority is still integral to our society and economy—perhaps even more so in a globalized age. While there are still many local industries, such as retail, being driven by middleman minorities, the dynamics have changed with the rise of e-commerce and technology. Modest financial success, in the cases of Jewish and South Asian digital entrepreneurs, has often been met with resentment by those who exemplify a disdain toward the virtues of capitalism. With the resurgence of antisemitism in 2024, conspiracy theories have run rampant, all of which boil down to a societal resentment toward success. But in all of this, neither capitalism nor middleman minorities should be made into a scapegoat.