What keeps modern man from religion? Of course, it may be contended that this question is quite misleading, no real question at all. It may be contended that modern man, in this country at least, is not in any special sense alienated from religion. Never, certainly not in the past century and a half, have church membership, religious belonging, or attendance at religious services been so high in the United States as in recent decades. That is well established and beyond controversy. Yet, acknowledging all this, we nevertheless cannot escape the feeling—and it is a feeling considerably buttressed by facts—that however impressive the high religiosity of the American people may be, modern man, even in America, seems to have become peculiarly insensitive to religion and its historic appeal; in a way, it might be said that, although the churches are full, the man of today, even in America, has become virtually religion-blind and religion-deaf. And so the question still remains: what keeps modern man from religion?

Through the past two hundred years, explanations or quasi-explanations of this phenomenon have accumulated in the West. It would not be very profitable to examine these attempted explanations in detail, and to point out their manifest in adequacies. I will merely mention three, perhaps the best known of the lot.

At the moment, the most popular of the three, at least in some intellectual circles, is the one derived as a sort of by product from the speculations of Rudolf Bultmann, the distinguished Protestant New Testament scholar and theologian, on the theme of “demythologization.” It traces modern man’s defection from religion to the discrepancy between the “primitive world-picture” of the Bible and the so-called “modern scientific world view.” That the world-picture of the Bible is “primitive,” that is, pre-scientific (flat Earth, three-story universe, etc.), is obvious enough; but that it is this discrepancy that has played any part in discrediting religion is more than doubtful. After all, this discrepancy was as real and as obvious in the thirteenth century, or even earlier, as it is today: recall the planetary orbs, the crystalline spheres, and the round Earth of the Ptolemaic system as against the flat Earth of the Bible. Yet religion did not suffer in the least on that account, nor does it today. The reader of the Bible either ignores the discrepancy or “demythologizes,” automatically and unconsciously, as he goes along. There is no point in this kind of explanation.

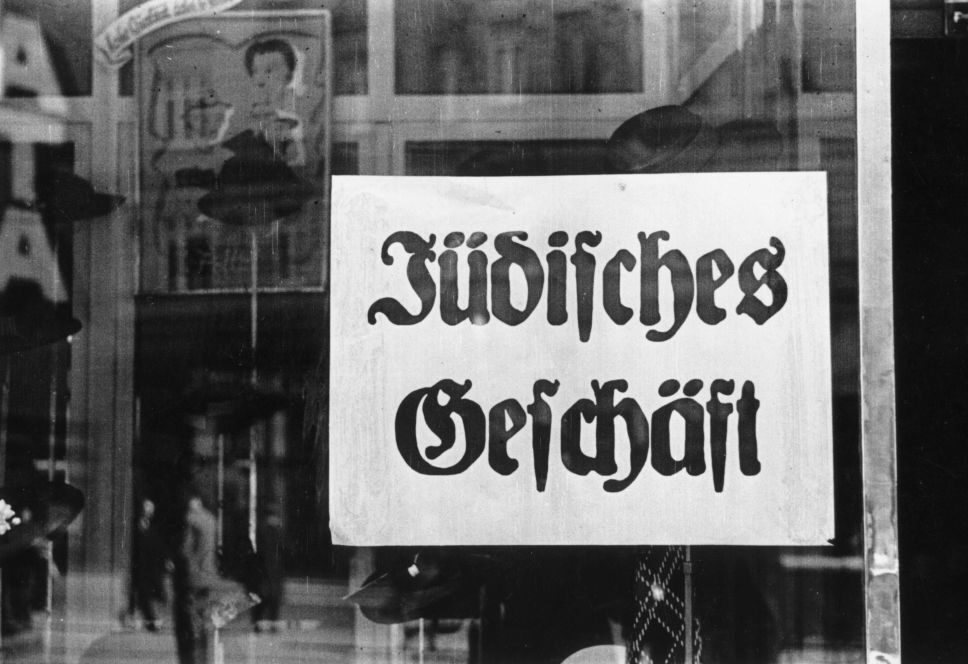

Perhaps equally popular, this time among what are called “socially conscious” intellectuals, is an explanation that stems from a kind of Marxist attitude, though Marx himself did not employ it. The church has so flagrantly sided with the ruling classes, it is alleged, that it has alienated the masses from religion. Whatever grain of truth there may be in this account so far as French anti-clericalism is concerned, it has no relevance whatever to this country or to Great Britain. In these countries there never has been any significant anti-clericalism. In the United States, moreover, the Catholic Church has always stood with the working people, while in Great Britain, the labor movement was virtually born in the dissenting chapel. And yet it is in these countries precisely that the problem is most perplexing today.

Finally, there are explanations stemming from the notion traceable to Dietrich Bonhoeffer, another distinguished Protestant theologian, that now, in our time, the world has at long last “come of age” (die mündige Welt). It is a world in which “modern man” can “stand on his own feet.” His alienation from religion is seen quite simply as a consequence of his spiritual and intellectual maturity. But this is, perhaps, the most futile explanation of all. Every age, from Homer’s to Bonhoeffer’s, a quick glance at our cultural history will tell us, has always tended to regard itself as having at last achieved “maturity”—a pretension that the succeeding age could only regard with amused contempt, knowing full well that “maturity” was really being achieved in its own, the succeeding time, and not before. This notion of finally achieving “maturity” in our time, and therefore no longer needing the “props” of religion, is one of the most pathetic illusions of Western mankind, and flies in the face of everything we know about man, phenomenologically and historically. No explanation here.

It appears to me that we ought to look in a rather different direction. There are a number of aspects of modern Western culture, there are a number of aspects of massive social and cultural forces that have been operative since the eighteenth century at least that seem to have affected modern attitudes to religion deeply. These are, I should say, (1) the triumph of the technological spirit in our time; (2) the triumph of the omnicompetent, all-engulfing modern Welfare State; (3) the triumph of mass society and the Mass-Man.

In other words, what keeps modern man from religion, it seems to me, is the pervasive dehumanization that comes of the technologized mass society which characterizes our world.

Let us examine each of these factors in some detail.

The Triumph of the Technological Spirit

It should be clear from the very beginning that I am not engaged in an indictment of technology, which is man’s way of coping with the harshness and recalcitrance of nature and, as such, is in the ordinary providence of God. It is not technology as such that is the problem; that has accompanied man through his history from the earliest times. It is the incredibly rapid, high-pressure elaboration of technology in the West in the past two centuries, and its consequences for the social and spiritual life of Western man, that constitute the problem. Sand-hogs, who work deep underground, descend into the bowels of the Earth gradually and by stages, to acclimate themselves, so to speak; failure to do so would result in the “bends,” agonizing cramps that sometimes prove fatal. Well, we are suffering from the social, cultural, and spiritual “bends” induced by an intense, high-pressure, technological progress that has compressed the work of many centuries, perhaps a millennium, in the brief period of hardly two hundred years. That is our problem.

The tremendous advance of science and technology, under high pressure, through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has engendered in modern Western man a monstrous sense of technological arrogance. Man, collective man, has come to see himself replacing God as “Maker and Master of all”; and, most ironically, he has come to see himself not only as Creator and Maker, but also as his own destroyer! The same technological spirit has promoted in Western culture a pervasive technological climate, with a mechanistic bias toward depersonalization and “thingification.” Everything about man—body, mind, and spirit—tends to be mechanized. One of the most telling indications of this way of thinking is the way modern Western man dreams of the World of Tomorrow. Beginning, with the Crystal Palace exhibition in London in 1851, or perhaps even earlier, the dream World of Tomorrow has been regularly projected as a prefabricated technological paradise—machines, mechanisms, technological wonders, gadgets.

Man, collective man, has come to see himself replacing God as “Maker and Master of all”; and, most ironically, he has come to see himself not only as Creator and Maker, but also as his own destroyer!

Perhaps the most deep-going effect of the technological spirit engendered by the incredibly rapid development of technology under high pressure has been our tendency to convert all human problems into technological problems, to be dealt with by some kind of machinery, mechanical or organizational. We have lost all sense of what a human problem really is, and therefore all sense of the profound distinction between knowledge and wisdom, which Gabriel Marcel has examined in such an illuminating way.

Technological problems are, in principle, always solvable; and the movement from problem to solution is negotiated by way of increasing technical knowledge and know-how. Human or social problems, on the other hand, however simple they may appear at first sight, are of an entirely different kind. The more we deal with a human problem, the more deeply we think ourselves and “live” ourselves into it, the more the difficulties and dimensions multiply. The more we pursue solutions to human problems, the more, like the horizon, they recede into the distance—until, finally, we come to see that human problems, utterly unlike technological problems, which are always solvable in principle, really have no solution; the best we can hope for is a kind of makeshift arrangement to get us over the immediate agony that has brought forth the problem. What is needed in human problems is wisdom, which goes deeper and deeper, rather than scientific-technical knowledge, which extends more and more widely.

This whole attitude runs so contrary to our technological prepossessions that it may, perhaps, be worthwhile to buttress it with some documentation. I am taking this documentation from what may appear the most unlikely sources, two of the acknowledged and certified liberals of our time. Wrote Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., the American liberal historian, some twenty years ago: “Man generally is entangled in unsolvable problems; history is consequently a tragedy in which we are all involved, whose keynote is anxiety and frustration, not progress and fulfillment.”1

And Gunnar Myrdal, the Swedish liberal sociologist, commenting on his book An American Dilemma, published in 1944, makes a like distinction between technical problems, which can in principle be solved, and human or social problems, which are, in their very nature, incapable of solution in the proper sense of the term (see the interview with Dr. Myrdal in U.S. News & World Report, November 18, 1963).

To see this is wisdom, even when it comes from a liberal; to overlook it is the great intellectual and spiritual pitfall of our technologized culture.

It should now be clear what is meant by the technological spirit which so dominates our culture. But it is precisely this technological spirit that is so fundamentally hostile to the sense of personal being and personal relation, which is at the heart of living religion. It is fundamentally hostile to the sense of transcendence, the sense of beyondness, that is the proper dimension of living religion. It is fundamentally hostile to the sense of human insufficiency and limitation, without which there can be no living religion. In all these respects—in its depersonalizing effect, in the erosion of the sense of transcendence, in its thoroughgoing mechanization of life—the technological spirit, so pervasive in our culture, tends to dry up the very sources of religion in modern life.

Perhaps the most revealing example of how our incredible preoccupation with technology at the expense of everything else has tended to relegate religion to the margin of life is President Nixon’s spontaneous exclamation that the landing of the astronauts on the moon was the “great event in the history of mankind since the Creation.” Mr. Nixon, who is so concerned—and, I think, sincerely—with his religious services in the White House, Mr. Nixon, the Christian, apparently forgot all about the “event” known as Jesus Christ! Mr. Nixon was only responding in a way reflecting the general trend of our culture.

The Triumph of the Omnicompetent Welfare State

Along with this overwhelming impact of the technological spirit on our culture, and therefore on our religion, we must take account of the effects of the Welfare State, of our Welfare Society, on religious attitudes in this country. Through the past century, the welfare services that ordinarily support human life in society have more and more passed over to the modern state, operating as a huge, centralized, bureaucratic, omnicompetent welfare agency. This has come as the culmination of the relentless secularization of life in the past four hundred years. In earlier days, through antiquity and the Middle Ages, into the sixteenth century, most of the welfare services that sustain life—taking care of orphans, jobless, old people, sick and incapacitated—were regularly rendered by family and friends within the scope and function of the church, which was thus bound to the people by a thousand threads of everyday welfare interest. For the Amish people, this is still a reality today. In April 1965, wind and flood did wide damage in the Midwest and destroyed many an Amish community. Groups of Amish people from the outside came to help their brothers rebuild their communities and their lives. On a TV news broadcast, a commentator noted that these days, when people are in trouble, there is one direction in which they look—to the federal government in Washington. But the Amish people don’t look to the federal government in Washington for help. They look to each other in their church.

That’s how it still is with the Amish people, but that’s how it was once all over in Christendom. I bring this forward not to encourage us to try to restore conditions long gone—that is a human impossibility—but to illustrate the profound changes that have taken place in recent centuries in our relation to religion and the church.

With the deep and thoroughgoing secularization of Western society, the hopes and expectations of the masses of people have steadily been turning from church to state, from religion to politics. This is a fact that no one, whatever his opinion or ideology, can deny, or has, in fact, denied. Consider how far this has gone in our own mass society, and our American society is only beginning to take its first steps in the direction of the Welfare State; if you want to see a Welfare State in its full development, look at Sweden. But already in our own society people have been so stripped of their human bonds in church and community that they are driven to look to the state for the most ordinary human associations and services. The state has not only become Big Father and Big Brother. It is actually brought to the point of having to supply to the forlorn members of the “lonely crowd” a state-appointed Good Friend. For what is the modern social worker but a state appointed Good Friend to the friendless denizens of mass society?

The modern state, in fact, becomes a divinized Welfare-Bringer. In the ancient world, the Hellenistic monarchs, and later the Roman emperors, prided themselves on being Welfare-Bringers (Euergetes, Benefactor), passing on the gifts of the gods to their subjects. They depicted themselves on their coins—the primary vehicle of state propaganda in those days which were without journalistic mass media, radio, or TV—as divinized figures holding a cornucopia, a horn of plenty, from which everything good is shown flowing to the grateful people. This is the modern Welfare State; even some of the ancient symbols are being revived in cartoons and pictures. The omnicompetent Welfare State thus becomes the modern substitute for God and the church, “from whom all blessings flow.”

Seen in this perspective, it is not difficult to understand why the church as a religious institution has become more and more marginal in the everyday life of the people. The broad scope of its interests has become drastically narrowed by the galloping secularization of life. What does the church do, what can it do, when the state takes over everything and comes to engage our deepest loyalties and emotions? Our religious feelings and religious interests have been more and more diverted from the attenuating church to the expanding state. Is it any wonder that people are losing their interest in religion? They identify themselves religiously, belong to churches, and attend religious services, but for very different reasons (I have discussed this elsewhere) than once bound them to religion and the church.2

The Triumph of Mass Society

All of these tendencies converge in the triumph of mass society. Mass society is not merely large-scale society. Mass society is a society of vast anonymous masses in which the individual person is increasingly atomized and homogenized, stripped bare of whatever particularities of background, tradition, and social position he may have possessed, and converted into a homogenized featureless unit in a vast, impersonal machine. In our homogenizing mass society, we have a horror of distinctions and differences, which are felt to be “discriminatory”; we want everybody to be like everybody else, only more so! This tendency toward homogenization, which John Stuart Mill saw and denounced a century ago as destructive of all real freedom (On Liberty, 1859; Mill called it “assimilation”), is now welcomed by liberal writers. “The ideal human society,” one recent writer promulgates as a self-evident truth, “is one in which distinctions of race, nationality, and religion, are totally disregarded. . . .”

Mass society is ruthless. Person-to-person relationships are systematically eroded in mass society and replaced by the remote impersonal connections of ever-proliferating state agencies and institutions. In this way, there is engendered that very curious phenomenon in mass society—“non-involved sociability” (the term is Riesman’s), a spurious sociability without personality, community, or responsibility.

What is this “non-involved sociability” of mass society? An illustration or two will help make it clear. Over five years ago, in March 1964, New Yorkers were startled to hear of a girl, Kitty Genovese, who was attacked and stabbed to death by an aggressor who had pursued her into the courtyard of a big apartment house in Kew Gardens, a respectable middle-class neighborhood in Queens. Awakened by the noise, thirty-four tenants showed enough curiosity to open their windows to see what was going on. They saw, and their curiosity satisfied, they shut their windows and went back to sleep! Kitty Genovese was then done to death. Subsequent inquiry elicited the explanation: “We didn’t want to get involved . . .” (all they had to do was to phone the police, without leaving their names, if that’s how they wanted it).

I have before me twenty-three such newspaper reports from eleven large cities across the United States in the past five years. I will merely mention one more, later the same year, in May 1964, also in New York, but this time in the Bronx. Here, too, a girl was attacked; she ran into an old four-story building, where her assailant caught up with her. (Fortunately, two policemen, some blocks away, heard her cries, and came to her assistance.) Here, too, the girl’s screams brought out people from the upper floors, who came out to see what was going on, saw, and went back to their business. And what was the business of the three men who came out from the first-floor apartment, looked, and went back? Believe it or not, they were members of a committee of one of the most liberal organizations in a city full of liberal organizations; they were engaged in drawing up resolutions on “racial justice,” and obviously couldn’t be bothered about the girl’s plight! As always, abstract humanitarianism, passing resolutions, making speeches, and the like reflected the erosion of concrete humanity.

But why did these people, from New York to California, act this way? They were probably no worse morally and culturally than the inhabitants of Paris or London in the Middle Ages; if anything, were you to take them at their word, they were considerably better. And yet, in London or Paris in the Middle Ages, which had no police departments, a “hue and cry” would arouse neighbors to come to the aid of anyone beset in the neighborhood. Why not in New York or San Francisco?

Because in a modern urban metropolis, unlike London or Paris in earlier days, there are no neighbors. In a mass society, people live in close propinquity, but there are no neighbors in the proper sense, no people bound by genuine community bonds. Therefore, while there are all kinds of sociability in a mass society, often factitious and contrived, it is a sociability false and spurious, a “non-involved sociability.” That is what mass society is like. Everything is big—Big Business, Big Labor, Big Government, Big Communications, Big Education, Big Entertainment, and . . . Big Religion. But in all this bigness, there is no room for the individual, the person, who is often reduced to nothing, and to less than nothing.

By atomizing, depersonalizing, and homogenizing the very substance of human life, mass society withers the roots of humanness, and thus, as Martin Buber has so well shown, it withers the roots of community and religion. It in fact leaves no room for religion and the church except as another Big Enterprise in mass society.

The technological spirit, the Welfare State, mass society: is it any wonder that in this cultural ambience religion tends to lose its proper and vital appeal? What keeps modern man from religion? The answer is here plain to see.

The criticism of the religious situation is a criticism of society and culture; this is true in a sense rather different from what Marx intended. The drying up of the living sources of religious response and religious consciousness in modern man means the dessication of the vital spirit of the culture itself, for the vital spirit of any culture, ours perhaps more than most others, is its religion. In religion, this development means that the religious task has become not primarily the saving of souls; before that even, it has become how to have human beings at all, how to have persons, not things; how to have persons, not personnel. That, it seems to me, has become the primary religious problem of our time.

This essay was previously published in Arguing Conservatism: Four Decades of the Intercollegiate Review, pp. 11–17.