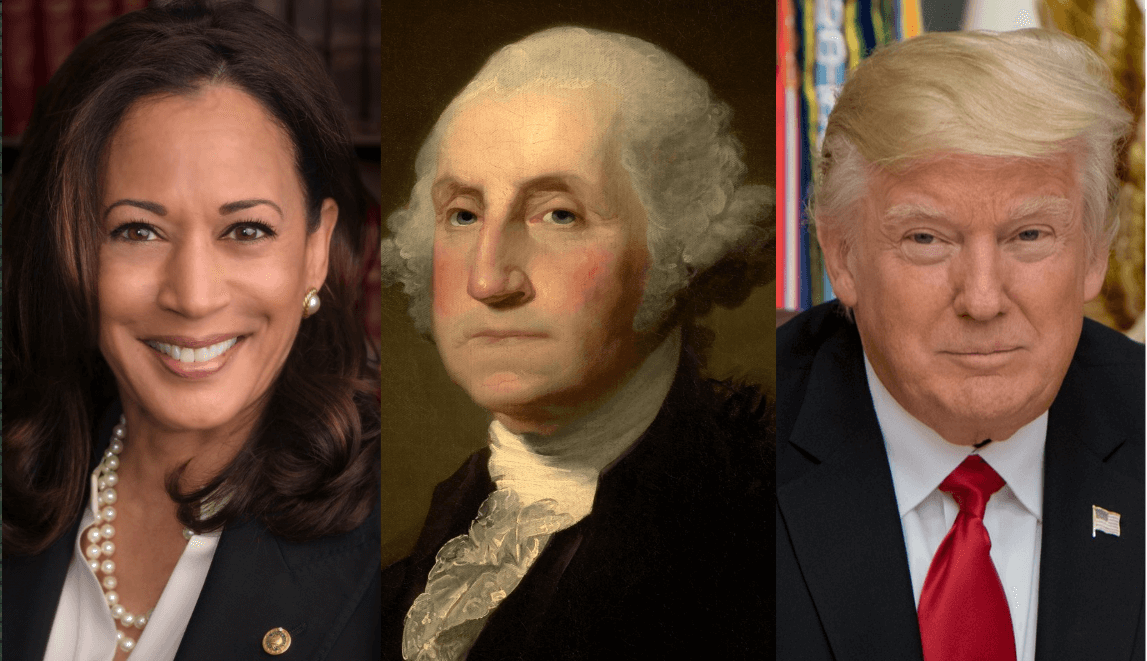

Donald Trump and Kamala Harris are both intimately familiar with the White House—Trump as a former president, Harris as next-in-line to President Biden—but the 235-year record of the presidential office has much to teach even these experienced leaders at the pinnacle of today’s politics. One of them will be sworn in next January, and with the burden of executive responsibility will come the possibility of living up to the highest and most salient examples from the past. But which former president imparts the most important lesson for the next commander-in-chief?

Modern Age asked nineteen historians, political journalists, and other thinkers to suggest which past president’s legacy affords the surest guide for the incoming administration—what achievements to emulate or failures to avoid, what character and virtues to cultivate, what philosophy of government and society to follow.

We encourage readers to make their own recommendations and share their thoughts with us @ModAgeJournal on X.com. —ed.

Our contributors are:

Sohrab Ahmari

Whoever is elected on November 5 will face a bedeviling “poly-crisis”: from the rise of China and the relative decline of U.S. primacy to an eroded industrial base, from the fentanyl scourge to declining prospects for families and youth. All that calls for a leader in the mold of Andrew Jackson, the founder of the Democratic Party, our first president from humble (as opposed to quasi-aristocratic) origins, and the first true populist in the American political tradition.

His sheer grit never fails to inspire. His body was home to a bullet lodged in it from dueling, desiccated by heavy smoking, and long sustained on little but diluted gin. He was toothless and prone to constant, violent coughing. A colorful and at times brutal life had left him unafraid to take on vested interests (the Second Bank of the United States), foreign rivals (such as Spain, from whose domains he forcibly extracted Florida), or even those ostensibly on his side: “Our federal Union, it must be preserved!” he famously yelled at Vice President John C. Calhoun amid the Nullification Crisis.

He did great and terrible things. Through it all, there was no denying his unblinking patriotism. Appropriately enough, on his last day as president, Jackson left the Oval Office in a sporty open carriage crafted from the timber of the U.S.S. Constitution, one of the Navy’s six original frigates, which had seen dramatic and triumphant action during the War of 1812—not unlike Jackson himself, the Hero of New Orleans. Tall, with his upright military bearing, his austere face topped by a thick flock of white hair combed straight back, Jackson sent the assembled crowd into a transport of tears as he exited the stage of history. He acknowledged his fellow citizens’ outpouring with a nod.

Sohrab Ahmari is a founder and editor of Compact and a contributing writer for the New Statesman.

F. H. Buckley

This year’s election won’t be decided by the extreme partisans on either side, neither by the MAGA crowd nor by the Trump haters. Instead, the winner will get the support of the 3 to 4 percent of voters who’ve been switching back and forth between the two candidates.

They have lives. They’re not invested in politics and bore more easily than people who are. They’re more concerned about their families, jobs, and churches than the flint-eyed true believers on either side.

And yet, they’re the people who can be trusted to get it right, when they’re aroused and when it matters. They were the people who tuned out the country’s racial problems, but when they were required to face them provided the crucial support for the 1964 Civil Rights bill. After 9/11 they supported the War on Terror, until they saw the pictures from Abu Ghraib. They never gave up on the principles of the Founders and are quick to recognize departures from them.

They’re liberals, and they know that that which is not liberal is not American. They know that criminalizing political differences and dividing us up by race is un-American. They’re liberals in the same way that the best of our presidents have been liberals. If I had to pick an exemplar, I’d choose the most popular president of the last century, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

F. H. Buckley’s most recent book is The Roots of Liberalism: What Faithful Knights and the Little Match Girl Taught Us About Civic Virtue (Encounter Books, 2024).

Jennifer Conner

Modern presidents would be wise to remember the story of the 1844 Democratic Convention and the nomination of James K. Polk. Polk received the nomination totally unexpectedly; on policy he was an established moderate, a compromise candidate, but personally he was so unknown that the opposing Whigs’ slogan against him was “Who is James K. Polk?”

Setting the particulars of Polk’s policy aside, the story of his nomination is a good reminder for a world in which we are tempted to assess political candidates and officeholders based solely on personal criteria or the “vibe” of an individual. Character and temperament are real qualities to consider in a leader, but our excessive emphasis on personality has led to ridiculous debates over which candidate would “make a better babysitter” or has more “dad energy” or is more “Brat summer.” Our politicians and elected leaders are often tempted to lean into these misguided criteria at the expense of clear policy proposals. Such candidates and leaders would do well to remember that there was a time in American history when leaders were chosen based on issues and policy rather than ego and personality—and it is largely based upon the first two that posterity will judge them.

Jennifer Conner is editorial associate at Modern Age.

Alan Pell Crawford

Thomas Jefferson’s first term in the presidency was such a stupendous success that his 1804 landslide reelection was hardly a surprise. “Taxes repealed; the public debt amply provided for . . . sinecures abolished; Louisiana acquired; public confidence unbounded”—so said Randolph of Roanoke, his fellow Virginian.

The embargo on trade with Great Britain, declared during Jefferson’s second term, proved catastrophic. He had hoped to teach a war-weary world how citizens of a free republic, united in defense of their rights, would respond to a crisis. A generation would remember Jefferson’s presidency for this disastrous exercise in “peaceable coercion,” though the embargo today is forgotten.

All that most Americans seem to know about Jefferson these days stems from allegations made during his first term—that he had a “concubine” back at Monticello satirized by his detractors as “Dusky Sally.” For this, Jefferson has been effectively canceled, and the lessons his long and admirable public life can teach us go unknown and unheeded.

Jefferson was an optimist with great faith in his fellow citizens and their capacity for self-government. His embargo, however well-intentioned, was an example of that confidence and might be seen in that light, if we reflect on his presidency at all. Did he put too much faith in the American people? Maybe, but we could use more of it, considering how little seems to exist in those fans of centralized power most hell-bent on saving “our democracy.”

Alan Pell Crawford is the author, most recently, of This Fierce People: The Untold Story of America’s Revolutionary War in the South (Knopf, 2024).

Donald J. Devine

The incoming president will pay the price of Ronald Reagan’s inability to get his gold commission to support his desire to end the United States’ fiat-money economic system. But Reagan was resourceful enough to assist Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker in acting as if he were following gold or some related monetary mixture. Although it led to a necessary recession, that solution pretty much continued supporting prosperity until the 2008 Great Recession, after George W. Bush’s Treasury and the Fed switched back to loose money.

As Ruchir Sharma’s new book What Went Wrong with Capitalism demonstrates (short version), debt has won, and the rest of the world resents the U.S. using its “reserve currency” to solve its debt problems by reducing the value of their currencies. There is no chance Harris would change course. But Trump tried to appoint Judy Shelton to the Fed, so if forced into doing so by events he might just follow Reagan and Volcker and allow the market to return us to monetary sanity.

Donald J. Devine is senior scholar at the Fund for American Studies and the author of America’s Way Back: Reconciling Freedom, Tradition, and Constitution (ISI Books).

Glenn Ellmers

Even if I weren’t a “Claremonster” and the author of a book about Harry Jaffa, I would still suggest that, objectively speaking, Abraham Lincoln’s presidency is the most instructive for our current crisis.

Here, then, are two lessons from Lincoln’s career that I think are especially valuable:

- Union, but . . .

Lincoln constantly reiterated his ardent desire to preserve the Union and was willing to go to great lengths to achieve that aim. But the moral approval of slavery, implicit in Stephen Douglas’s “popular sovereignty” doctrine, was where he drew the line. There are some things a free people, under a republican form of government, cannot tolerate in principle. How and when to bow to necessity, and when to fight for that principle—that’s the hard part. But Lincoln always insisted on clarity over the moral question.

- All one thing, or all another

Closely connected with the point above was Lincoln’s observation in his 1858 “House Divided” speech that as regards slavery and freedom, the United States must “become all one thing, or all the other.” In every society, the citizens must agree on certain basic truths that define the essence of the regime. There can’t be diversity over the meaning of what a man or a woman is, who gets to be a citizen, or whether or not we can redefine human nature according to our whim.

The parallels to today seem obvious. Let us hope God gives us another statesman.

Glenn Ellmers holds a Ph.D. in political science from Claremont Graduate University. He is the author of The Soul of Politics: Harry V. Jaffa and the Fight for America and is the Salvatori Research Fellow in the American Founding at the Claremont Institute.

Gary L. Gregg II

More than three decades ago, Forrest McDonald quipped that the history of the American presidency has been one of steady decline since George Washington left the stage. We should feel that this is much more apt a statement today than when it was made. Our presidents can’t be Washington, but they could at least carry themselves as people worthy of inheriting his high office.

Washington carried himself with dignity and strength. He always spoke and conducted himself knowing he was the symbolic embodiment of a greater people and greater causes than himself. He held himself and his tongue to exacting standards and always strove to raise his followers rather than appealing to the least common denominator. He demonstrated selflessness, both in resigning power voluntarily and in serving when he had nothing to gain and everything to lose. He warned us about the dangers of thinking of ourselves as members of political parties rather than as one nation. He understood the centrality of religion and morality to our political culture and upheld the Constitution above any temporary cause—including his own. In his rhetoric and his actions our Washington called his people together, healed wounds, created a national bond of friendship, and founded a people that would shape the world.

In our age of informality, profanity, selfishness, demagoguery, ideology, political spectacle, and short-sighted political thinking, Washington calls on our chief executives to hold themselves to higher standards and invite the American people to rise with them again and be worthy of the great nation we all have been blessed to inherit.

Gary L. Gregg II holds the Mitch McConnell Chair in Leadership at the University of Louisville and is director of the McConnell Center.

Kevin R. C. Gutzman

Among the urgent imperatives facing the country regardless of who wins the 2024 election is one neither presidential candidate is mentioning: to come to terms with the looming fiscal calamity of Medicare and Social Security insolvency. Politicians have long recognized that voters will reward them for promising something for nothing, and so they have tuned up their fiddles as this particular fire began to burn. But statesmanship, that more-or-less forgotten concept, will require leadership in Congress, in the executive branch, or—optimally—in both, to grab the nettle and give it a good, hard squeeze. Presidents Truman, Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton, among others, all made substantial steps in the budget-paring direction. It did not necessarily win them approval from the electorate, but a statesman is one who leads where the country needs to go. Let us hope Donald Trump or Kamala Harris surprises us by being a statesman.

Kevin R. C. Gutzman is professor of history at Western Connecticut State University. His latest book is The Jeffersonians: The Visionary Presidencies of Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe.

Jacob Heilbrunn

Like his fellow Ohioan Ulysses S. Grant, Warren Harding is often unfairly dismissed as a presidential buffoon. Though his first term was truncated in 1923 when he suffered a fatal heart attack, Harding is more than worthy of emulation for the courageous moral spirit that he displayed on several occasions.

The first was his visit to segregated Birmingham in October 1921 to celebrate the city’s semicentennial. To the astonishment of a crowd of over one hundred thousand attendees, Harding delivered a speech at Capitol Park on race relations demanding political (not racial) equality for African Americans. “I would say let the black man vote when he is fit to vote; prohibit the white man voting when he is unfit to vote,” said Harding. “Whether you like it or not, our democracy is a lie unless you stand for that equality.” What a contrast to his malignant predecessor Woodrow Wilson, who resegregated the federal government!

The second was his commutation shortly before Christmas in 1921 of the ten-year prison sentence of Eugene V. Debs. A vengeful Wilson had the outspoken socialist and labor leader arrested for ten counts of sedition for a speech he gave in June 1918 in Canton (decrying the military draft) that supposedly violated the 1917 Espionage Act. In 1920 Debs campaigned for the presidency from jail, winning a million votes. Harding ended Wilson’s witch hunt, welcoming Debs to the White House for a private meeting. Whoever wins the presidency might well profit by channeling Harding’s magnanimity and seeking a return to normalcy.

Jacob Heilbrunn is editor of the National Interest and author most recently of America Last: The Right’s Century-Long Romance with Foreign Dictators (Liveright, 2024).

Bill Kauffman

If Donald Trump wins, he ought to take a cue from the other president to have served two nonconsecutive terms, the noble Buffalonian Grover Cleveland. Upon returning to office in 1893, President Cleveland appointed a genuinely anti-imperialist secretary of state, Walter Q. Gresham, who opposed the annexation of Hawaii and warned his countrymen that if Americans refused to “stay at home and attend to their own business” we would “go to hell as fast as possible.” Our modern Gresham—say, Andrew Bacevich, Tulsi Gabbard, or Rand Paul—could begin the long-overdue task of dismantling the American Empire; disentangling its tendrils from Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and everywhere else; and re-localizing American political, economic, cultural, and social life.

If Kamala Harris wins . . . well, spurning the temptation to make a William Henry Harrison joke, I propose that she take Chester Arthur as a model. Vice President Arthur was lightly regarded as ethically dubious and a fastidious clotheshorse, but as successor to the assassinated James Garfield he turned out to be honest and competent, if more or less an orthodox Gilded Age Republican. Alas, Harris gives no indication that she is capable of reenacting the Arthurian legend, so perhaps the best we can hope for is that a President Harris might live up to H. L. Mencken’s (somewhat unfair) eulogy for Calvin Coolidge: “He had no ideas, and he was not a nuisance.”

Bill Kauffman is the author of eleven books, among them Dispatches from the Muckdog Gazette (Holt) and Look Homeward, America (ISI).

Daniel McCarthy

Joe Biden has been a second Jimmy Carter, presiding over a nation bedeviled by inflation, humiliation abroad, and a sense of helplessness as new crises erupt worldwide.

There’s a parallel, too, in the way liberals imagined Carter to be a repudiation of Richard Nixon, just as Biden was supposed to be a repudiation of Donald Trump.

Yet far from being permanently discredited after Watergate, the Republican Party quickly regained the White House from Carter, led by a man progressives considered every bit as bad as Nixon.

The Carter era was a prelude to Ronald Reagan. The Biden years may prove only an interregnum between Trump administrations.

But whichever candidate succeeds Biden, Reagan is the right model for repairing the country after a Carter-like presidency—the real Reagan, that is, not the zombie Reagan of neoconservative mythology.

Reagan was a realist in foreign policy who pursued bold diplomacy with the Soviet Union, ushering the Cold War to a peaceful conclusion hardly anyone dared imagine. He withdrew troops from Lebanon rather than being lured into a Middle East war after 241 U.S. military personnel were killed in the bombing of their barracks in Beirut. He used military force when necessary, but he understood its limits better than any president for a quarter-century after him.

Reagan made Americans proud again and celebrated the working man as well as the entrepreneur. He fostered prosperity not through tax cuts and deregulation alone but in combination with wise industrial strategy. On social policy and immigration his example is insufficient, but the Gipper remains the starting point for a successful modern presidency.

Daniel McCarthy is editor in chief of Modern Age.

Noah Millman

After promising a return to normalcy, the Biden years have instead proved tumultuous, with the first significant inflation in decades, an unprecedented surge in migrants seeking asylum, two major wars launched by adversaries against friendly countries, and the perpetuation of the cultural divisions that have torn America’s civic fabric. Four years ago, when Modern Age asked for a fictional character I would like to see as president, I named Cordelia, King Lear’s youngest daughter, to soothe our raging sovereign, the American people. This year, asked to pick a past president best suited for our moment, I once again pick an emblem of stability: President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Eisenhower inherited a stalemated war and a society wracked by labor strife and vulnerable to demagoguery. A conservative pragmatist rather than an ideologue, Eisenhower settled the Korean War on the best terms available, consolidated America’s position in the Cold War, and carefully orchestrated the end of the McCarthy era. He rebuked Southern segregationists, signing the first major Civil Rights Act since Reconstruction and enforcing Brown vs. Board of Education. He signed the Refugee Relief Act and also secured the southern border. He built the interstate highway system, founded NASA, signed the National Defense Education Act, and promoted nuclear power. He expanded Social Security, kept inflation low and employment high, and balanced the budget, in part by refusing to cut taxes.

It’s almost embarrassing how much of Eisenhower’s agenda remains relevant to our era.

Noah Millman is theater and film critic for Modern Age and writes the newsletter Gideon’s Substack.

Henry Olsen

Both of this year’s candidates have been guilty at times of dialing the rhetoric up to eleven to demonize their opponent and whip their supporters into a frenzy. The winner should take a page from our early history and emulate Thomas Jefferson’s behavior after the contentious election of 1800.

Contrary to popular belief, our Founding Fathers were not disinterested patriots all of the time. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were both ardent revolutionaries, and each played a key role in the drafting of the Declaration of Independence and in diplomacy (Adams as ambassador to Great Britain; Jefferson as ambassador to France) during the young nation’s early years. Yet these one-time brothers in arms levied political scorched-earth warfare against each other when they faced off for the presidency in 1800.

Adams and his Federalist Party were said to be England-loving monarchists, while Jefferson and his Republican Party were accused of being atheist allies of French Jacobin revolutionaries. Jefferson was elevated to the presidency only when the Federalist Alexander Hamilton decided that he was preferable to the man with whom he was tied, Aaron Burr. (At that time, electors did not vote separately for president and vice president, and Jefferson and his putative running mate were tied.)

Jefferson could have sought vengeance on the Federalists. Instead, he sought conciliation. He understood that many Federalist voters merely disagreed with him and were not implacable foes. He used his inaugural address to begin the national healing process. “We have called by different names brethren of the same principle,” he intoned. “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

Jefferson’s approach worked, both for the public’s interest and for his party’s. Political temperatures dropped as he showed that citizenship was more important than party—country above party, if you will. Many Federalist voters, seeing their foe act temperately, started to move over to the Republican Party. Federalist support collapsed precipitously; by 1804, the party was in terminal condition and never mounted a sustained challenge until it dissolved in the early 1820s.

Either Trump or Harris would have to face down the party’s base if he or she were to pursue this approach, but either has the political capital to do so if he or she insisted. Trump in particular has that ability, and the change in attitude he would display—from pledging retribution to offering peace and harmony—would be so unexpected that one cannot see how Democrats could effectively respond.

Americans who are not extreme partisans want our Thirty Years’ War to end. They would likely reward a president—and his or her party—handsomely if that prospect were seriously offered them.

Henry Olsen is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and host of the podcast “Beyond the Polls.”

Jeff Polet

“When small men cast long shadows, the end of the day is near.” Does the quality of our two candidates suggest we are in our last days?

Surely in a nation of 340 million people we can find someone with the qualities that made Gerald Ford a good man and a respectable president: courage, character, cooperation, compromise, conviction, civility, and competency. He understood the importance of doing good things instead of great things, of elevating national interest over self-interest. Recognizing political and constitutional limits, he didn’t make promises he didn’t think he could keep.

His lack of ambition for the presidency made him especially desirable as president. His approach to governing—cooperate where you can, stand your ground where you must, back off when consensus is not available—demonstrated prudence and a democratic temperament. He didn’t think bipartisanship was a good in itself but saw that it was necessary to achieve good outcomes.

He recognized limits, both his own and that of the office. He properly evaluated his rhetorical skills, knowing he was a workhorse and not a show horse.

Ford didn’t tell lies or disparage his opponents. He understood, as did Washington, that the president had an obligation to model virtue and an honorable patriotism to the nation. One can be a decent president just by being decent. He halted the decline of trust in our institutions rather than exacerbating it. Never really wanting to be president, and following three egoists with expansive appetites, he helped cut the office down to size.

Jeff Polet is director of the Ford Leadership Forum at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation.

William Ruger

The presidency of George W. Bush provides an object lesson for all future executives, Republican or Democrat, in how not to conduct American foreign policy.

One could argue that Bush was doomed from the beginning due to his choice of advisors and appointees, from Dick Cheney as vice president to a slew of neoconservatives who drove the ship of state into the rocks. So the first lesson from Bush II is to be cautious about whom you choose for your administration because they may fail you and the country. They can give you bad advice rooted in personal agendas and problematic theories about the nature of the world. They can maneuver you into quicksand that is difficult to get out of. Indeed, they can help wreck your presidency beyond the national security realm, as the Iraq War did for Bush.

Blaming advisors doesn’t absolve Bush the Younger of his own mistakes; he made the final calls, after all. Still, personnel is critical to the success or failure of foreign policy. Given the failures of the establishment in both parties over the last thirty years, future presidents might want to take President Donald Trump’s advice that it is better to hire talented people who are new to government and have practical ideas rather than “those who have perfect resumes but very little to brag about except responsibility for a long history of failed policies and continued losses at war.”

Another critical lesson to learn from George W. Bush is the danger of idealism in foreign policy. The presidents who have been most successful in the realm of foreign policy, starting with the master realist Washington himself, were able to use realism in practice to advance our country’s interests and ideals. They navigated prudently and without zealousness getting the better of them. They understood, as Washington did, our geostrategic advantages and what those meant for our security. They understood the importance of power and interest—and the downsides of war and foreign commitments. They knew when to push, as Grover Cleveland did against Britain in the Venezuela Boundary Crisis, but they also knew when to retrench, as Ronald Reagan did in Lebanon.

Bush’s idealism, seen in his 2002 National Security Strategy and stated plainly in his second inaugural address, stood in contrast to those realist masters. His idealistic vision cost Americans dearly in the blood of patriots and the wallets of taxpayers. This idealism was often deaf to what prudence would counsel, as demonstrated in the Iraq War, the nation-building effort in Afghanistan, and the expansion of U.S. commitments beyond what national security required. Idealism, from Clinton to Bush to Obama, squandered the unipolar moment. Future presidents shouldn’t just master the history of our successes but also study our moments of failure.

William Ruger is the president of the American Institute for Economic Research.

Troy Senik

Grover Cleveland has been unusually salient this election season thanks to Donald Trump’s attempt to replicate his feat of serving nonconsecutive terms. Too little attention has been paid, however, to the trait that was most responsible for Cleveland’s political resurrection: brutal honesty.

At a time when Cleveland’s Democratic Party was increasingly in the grips of a populist mania to stoke inflation (in order to ease the debt burdens of its Southern and Western constituents), the former president managed to secure a third consecutive nomination in 1892 despite standing athwart his base in support of sound money. The policy may not have been popular, but the candor it demonstrated—compounded by Cleveland’s lifelong reputation for putting principle above political expediency—was.

For proof that this spirit has gone out of American politics, behold the arms race between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris over who can offer the most expansive tax exemptions and subsidy packages to politically valuable constituencies. None of these policies are ever discussed in terms of their impact on the federal budget, the coherence of the tax code, or the necessity of making difficult tradeoffs. They rely instead on the most visceral of political appeals: you’ll get yours.

A politician intent on elevating the national interest over such parochial ones might not find a market in 2024, but that owes, at least in part, to habituation. If we expect voters to make reasoned judgments about the future of the country, then presidents ought to start addressing them as if they’re capable of being reasoned with.

Troy Senik is a former presidential speechwriter and the author of A Man of Iron: The Turbulent Life and Improbable Presidency of Grover Cleveland.

Amity Shlaes

My president from the past is not one president but a pair: Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge. In 1920, the year Harding ran for president and Coolidge for vice president, the nation struggled under the burden of World War I debt. The Republican Party was badly split between its growing progressive faction and retro conservatives.

Rather than attempting compromise—or, as we might say today, “fusion”—Republican leadership opted for pure old. The platform the leaders wrote promised to “end executive autocracy”—a swipe at not only President Woodrow Wilson but also some fellow GOP progressives. The platform promised “rigid economy” and government cutbacks. It assailed the “staggering” tax burden.

In a display of humility that today might be mischaracterized as weakness, Harding and Coolidge hewed to the platform. Candidate Harding promised “not heroics, but healing, not nostrums, but normalcy, not revolution but restoration.” If you can get past the unrelenting alliteration—alliteration was Harding’s tic—you’ll find this is a brave statement.

In his two and a half years as president, Harding delivered, cutting the government, cutting taxes, and appointing as Treasury secretary Andrew Mellon, a financial wizard so astute he could and did cut the federal debt by one-third. After Harding passed away in 1923, the new president, Coolidge, forwent the ego hit of rebranding. Instead, Coolidge plodded ahead, vowing to finish what Harding couldn’t—and “to perfection.” The seamless transition and commitment to government restraint yielded a strong economy.

Coolidge bored intellectuals; H. L. Mencken once compared the Coolidge voter to a banquet guest who turns from a feast table and “stay[s] his stomach by catching and eating flies.” Yet those voters were numerous. In the three-way race of 1924 Coolidge took an absolute majority, beating a new Progressive Party and Democrats combined. Conservative humility can deliver more than showmanship.

Amity Shlaes is author of the New York Times bestsellers The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression (Harper) and Coolidge (Harper). She chairs the board of the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation, which is home to the Coolidge Scholarship for Academic Merit.

Kelley Beaucar Vlahos

The next president can learn from our forty-fourth commander-in-chief Barack Obama, but as a caution of what not to do when he or she gets into office.

Obama was new to Washington, having zoomed in from a seven-year stint as an Illinois state senator followed by only three years as a U.S. senator before winning the presidency in 2008. The man who had campaigned on a wave of “hope and change” was suddenly faced with the conundrum of paying back the Democrats who helped him win and facing an empty bench of experienced bureaucrats on his team.

So he turned to Clintonistas to fill his cabinet, including his chief primary-campaign rival, Hillary Clinton, whose small army of baby boomers had been waiting out the George W. Bush years in high-powered think tanks and consultancies throughout the Beltway.

To say Obama disappointed his base in this regard would be an understatement. He had won in part because he wanted to end the war in Iraq. Hillary had been an integral supporter of that war, as she had been for all U.S. interventions since she was First Lady. Her legacy as Obama’s secretary of state is one of pushing for revolution in Moscow and Kyiv and the violent overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi. Today we have an endless war in Ukraine and a failed state in Libya. The next president needs to avoid the pressures of political favors and a misplaced desire for continuity. If she or he promises change, all the retreads need to be sent packing.

Kelley Beaucar Vlahos is a senior advisor for the Quincy Institute and editorial director at Responsible Statecraft.

Tom Woods

Poor Warren Harding: despised by historians, he turns up reliably at the bottom of their worthless presidential rankings. Most Americans, if they can even place him chronologically, remember little about the twenty-ninth president except being told stories, in seventh grade, of his alleged corruption.

Whatever Harding’s faults, though, he had one thing going for him: when he urged a “return to normalcy,” he meant it. No more schemes of foreign intervention to make the world safe for democracy, no more unprecedented wartime spending, no more novel expansion of federal power.

By the time Harding took office, the economy was in bad shape: he was confronted with double-digit unemployment, terrible production numbers, and the progressive Herbert Hoover demanding action.

But what did Harding say in his inaugural address (a speech no teacher urged you to read)? A sample: “No statute enacted by man can repeal the inexorable laws of nature. . . . The economic mechanism is intricate and its parts interdependent, and has suffered the shocks and jars incident to abnormal demands, credit inflations, and price upheavals. . . . There is no instant step from disorder to order. . . . Any wild experiment will only add to the confusion.”

Thus Harding, in the face of turmoil, promised no program of grand reconstruction and delivered no messianic speeches. He said simply, We shall return to normal. Abandon the wild abnormalities of the past and let the country heal. (And heal it did: Joseph Schumpeter said the depression of 1920 in itself proved that economic downturns were self-reversing without government intervention.) Sound advice, economically and in every other way.

Tom Woods is the New York Times bestselling author of thirteen books and winner of the 2019 Hayek Lifetime Achievement Award.