It is hard not to be struck by the similarities between Thucydides’ Athens and the post–Cold War United States. Admittedly, Periclean democracy, in which only a fraction of the men made political decisions without the participation of women and slaves, is very different from modern American democracy, which, whatever its other faults, at least has a much broader franchise.1 In other respects, though, comparisons seem apt.

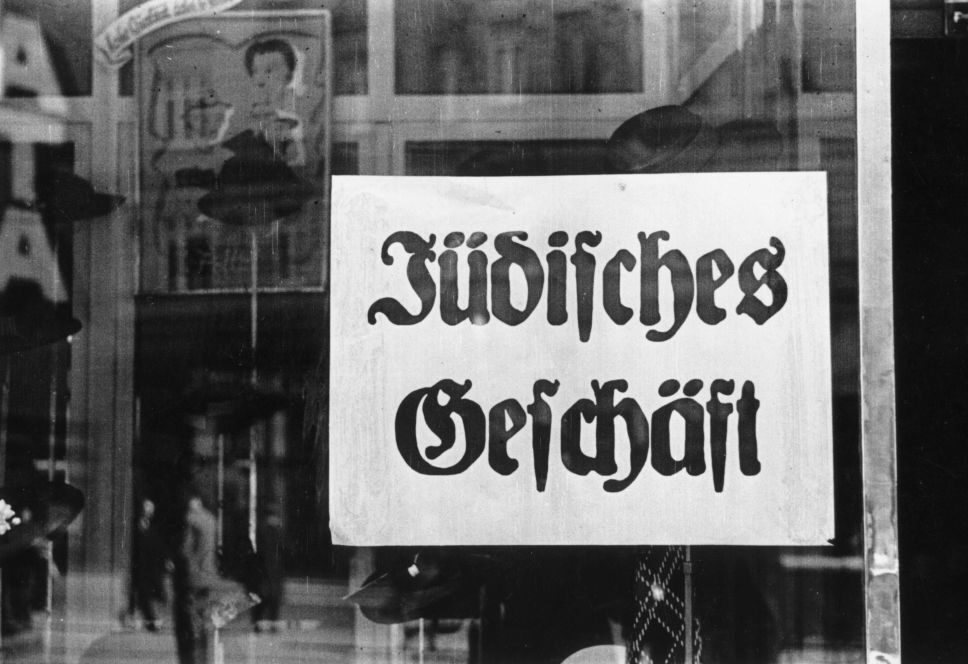

Athens, for example, played the key role in the victory of Greeks in their ancient world war with the Persian Empire at Marathon and especially Salamis; the United States would double that, as a victor over both fascism in 1945 and communism in 1989. America’s victories over Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan placed it in the center of a postwar web of multilateral and bilateral alliances intended to keep the long peace of the Cold War, and its unexpected, bloodless victory over the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War ushered in its “unipolar moment,” in which the United States bestrode the world like a colossus for a quarter of a century. As with ancient Athens, America could claim not only that its hegemony had emerged from victorious wars but also that its allies joined for the most part willingly.

Both democratic hegemons would eventually overplay their hands, however. The overbearing power of Athens inspired fear among the Spartans and the rest of the Greek world. America’s post–Cold War “hyper-power” annoyed allies, who saw themselves as increasingly subordinate in an American-dominated hierarchical order, and eventually spurred the rise of new rivals such as Russia and China, who are now pushing back against its hegemonic position at both ends of Eurasia.2

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has engaged in numerous wars of choice. So far, their failures have been catastrophic mostly for the unfortunate people of Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria, whom U.S. leaders believed they were liberating from Islamo-fascism, nuclear dictatorship, civil war, and massive human rights violations. It is not unreasonable to fear that Ukraine, Gaza, and Taiwan could become today’s Epidamnus and Corcyra, in which conflict in small, peripheral states becomes the spark that ignites the conflagration of great power war.

There is also a reflection of Pericles, the Athenian foreign-policy restrainer who nonetheless set the stage for overreach, in President George H. W. Bush. In an effort to bolster the flagging spirits of the Athenians early in the Peloponnesian War in his “Funeral Oration,” Pericles perhaps imprudently praises the splendor of imperial Athens, which has “forced every land and sea to be the highway of to our daring . . .” and called upon his fellow Athenians to fall in “love” with her.3 The first President Bush declined to publicly dance on the fallen Berlin Wall but privately refused to rule out post–Cold War NATO expansion, a central cause of today’s Ukraine war.4 As a candidate, his son urged America to be a “humble nation” but after 9/11 boldly proclaimed that “it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world,” echoing Pericles’ imprudent rhetoric in his Funeral Oration.5

Nor can we ignore the echoes of Nicias and Alcibiades making the case against and for the Sicilian Expedition in the debate between Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz about how big a force was necessary to overthrow Saddam Hussein in 2003.6 We can also recognize Athens’s feckless Sicilian allies the Egestans, falsely promising to underwrite the Sicilian Expedition with wealth they do not have, in America’s misbegotten Iraq intervention, which was similarly launched in the mistaken belief—encouraged by Iraqi exiles—that Saddam Hussein had reconstituted his weapons of mass destruction program.7

While Thucydides’ History reads a lot like a Greek tragedy, in which the disastrous outcome seems inevitable, it is possible to learn some positive lessons from it. For example, leadership matters, and if Athens had better leaders than those who succeeded Pericles, it might have prevailed in the Peloponnesian War.8 Thucydides gives up looking for another Pericles by Book VIII, calling the “mixed regime” of the Five Thousand “the best government that [Athens] ever [had], at least in my lifetime.”9 Truly great statesmen and -women have always been rare, and today we no longer live in the era of great men (or even women).10

But the most important lesson that Thucydides could teach post–Cold War America is the virtues of prudence and restraint in the acquisition and wielding of overwhelming power. Unfortunately, like the Athenian delegation at Sparta before the Peloponnesian War, the current American foreign-policy elite combines an arrogance about the country’s unrivaled power with a self-righteousness based upon its undeniable domestic virtues and contributions to defeating odious regimes and undergirding an efficient and just international order.11

Those things can be true at the same time that rivals and even allies chafe at a dominant America that throws its weight around on a regular basis. As Pericles candidly reminded the Athenians, even their democratic empire was a tyranny, and Americans should have taken the point that humility and restraint ought to have been their watchwords during the United States’ unipolar moment.12 Perhaps one of the few upsides to its end and the return to great-power politics is that overt balancing by other states may finally still America’s post–Cold War restlessness by imposing upon it the need to think hard about its commitments and resources in a way it has not had to do over the last quarter of a century.13

Of the grand strategic options available to the United States today, the most Thucydidean is some version of restraint or offshore balancing rather than more activist approaches such as deep engagement, liberal internationalism, or conservative primacy. This is because only the former acknowledge the superiority of balance over preponderance of power as an objective of statecraft. This remains Thucydides’ most enduring lesson for us, as a balance-of-power, realist reading of the History makes clear.

- Though see Loren J. Samons II, What’s Wrong With Democracy: From Athenian Practice to American Worship (Berkeley, CA: The University of California Press, 2004). ↩︎

- Christopher Layne, “This Time It’s Real: The End of Unipolarity and the ‘Pax Americana,’” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 1 (March 2012): 203–13. ↩︎

- Robert B. Strassler, ed., The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War (New York: The Free Press, 1996), 2.41.4 and 2.43.1. [Hereafter, LT, {book}, {paragraph}, {line}]. ↩︎

- Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson, “Deal or No Deal? The End of the Cold War and the U.S. Offer to Limit NATO Expansion,” International Security, Vol. 40, No. 4. (Spring 2016): 7–44 and John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 93, No. 5 (September/October 2014) at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2014-08-18/why-ukraine-crisis-west-s-fault. ↩︎

- Compare “The Second Gore-Bush Presidential Debate,” October 11, 2000, at https://www.debates.org/voter-education/debate-transcripts/october-11-2000-debate-transcript/ with “President Bush’s Second Inaugural Address, National Public Radio, January 20, 2005. ↩︎

- Michael E. O’Hanlon, “Shinseki vs. Wolfowitz,” Brookings, Tuesday, March 4, 2003, at https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/shinseki-vs-wolfowitz/. ↩︎

- LT, 6.6.2 and 6.46.1–5 foreshadow J. D. Maddox, “The Day I Realized I Would Never Find Weapons of Mass Destruction in Iraq,” The New York Times Magazine, January 29, 2020, at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/29/magazine/iraq-weapons-mass-destruction.html?referringSource=articleShare. ↩︎

- Daniel L. Byman and Kenneth M. Pollack, “Let Us Now Praise Great Men: Bringing the Statesman Back In,” International Security, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Spring, 2001): 107–46. D. M. Lewis, “The Archidamian War,” in David M. Lewis, John Boardman, J. K. Davies, and M. Ostwald, eds., The Cambridge Ancient History [Vol. 5] The Fifth Century, B.C. (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 432 argues that “Athens had won the war.” Also LT, 518–19. ↩︎

- LT, 8.97.2. ↩︎

- Brian Rathbun, “The Rarity of Realpolitik: What Bismarck’s Rationality Reveals About International Politics,” International Security, Vol. 43, No. 1 (Summer 2018): 7–55. And they do not always last very long, as Thucydides himself recognized. S. N. Jaffe, “The Regime (Politeia) in Thucydides” in Ryan K. Balot, Sara Forsdyke, and Edith Foster, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Thucydides (New York, Oxford University Press, 2017), 402. ↩︎

- Michael C. Desch, “America’s Liberal Illiberalism: The Ideological Origins of Overreaction in U.S. Foreign Policy,” International Security Vol. 32, No. 3 (Winter 2007/08): 7–43. George F. Kennan, American Diplomacy, 1900-1950 (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1951), 6 similarly deplores the “torpor and smugness” of America’s foreign policy elite. ↩︎

- LT, 2.63.2. ↩︎

- The Corinthians in Book I describe the Athenians as “born into this world to take no rest . . . and to give none to others” (LT, 1.70.9). They are, in Thucydides’ view, like Alcibiades, incapable of not indulging “their tastes beyond what [their] real means would bear,” and this, in his estimation, “had not a little to do with the ruin of the Athenian state” (LT, 6.15.3). It was only after the Sicilian debacle that the Athenians, including Alcibiades, embrace prudence and restraint. See LT, 8.1.4, 8.24.4–5, and 8.86.4–5. ↩︎