In 1860, Jacob Burckhardt published The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, which helped to invent—some would say created—the Renaissance as a historical period. Until the years following World War II Burckhardt’s fame in the German and Anglo-Saxon worlds was largely the consequence of this book. The reexamination of the European and especially the German past led to a new interest in and a reevaluation of the role of Burckhardt as a liberal-conservative thinker, historical innovator, teacher, prophet, and philosopher of history.

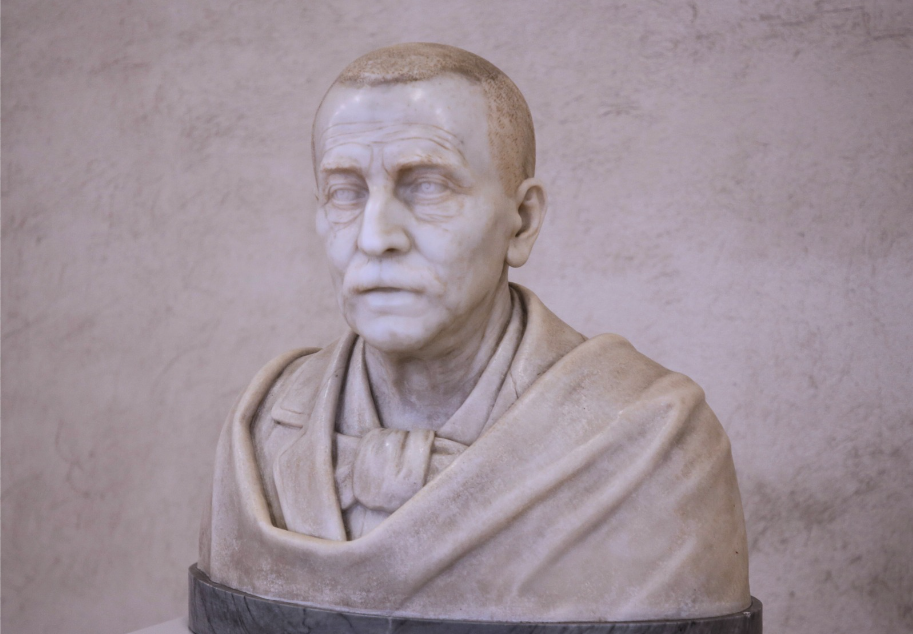

Jacob Burckhardt was born in 1818 in Basel, Switzerland, and died in that same city in 1897. His family was patrician rather than bourgeois and had long been involved in the economic, political, and cultural life of Basel. Because of the location and culture of Basel, Burckhardt was as European in outlook as he was Swiss-German. He was educated at the University of Berlin, where he was von Ranke’s student, and at the University of Bonn, where he and Carl Schurtz were both members of the circle of Professor Gottfried Kinkel. Early in 1845, he became editor of the important conservative newspaper Basler Zeitung, a post in which he served for eighteen months. In 1844, he was given the honorary title of professor at the tiny University of Basel, a post he held for virtually the remainder of his life (until 1895). When von Ranke retired from his post at the University of Berlin, Burckhardt was chosen as his successor. Burckhardt declined the appointment, no doubt because Prussia had become the epitome of everything in the modern world that Burckhardt detested: centralization, growing democratization, the commercial spirit, militarism, and a crass and vulgar smartness. He preferred culture to conquest. Besides, his colleagues at the University of Basel, Johann Bachofen and the young Friedrich Nietzsche, made the university one of the greatest constellations of genius in nineteenth-century Europe.

Burckhardt’s lifestyle was one of ascetic dedication. He saw his mission as the instruction of his fellow citizens of Basel. He never married and, although he possessed independent means, lived in great simplicity. He never lectured at universities other than Basel and traveled to London, Paris, and Italy only in order to study the great art and architecture of the past.

Burckhardt viewed history as an act of contemplation and the creation of culture and its study the highest adventure of the human spirit. Cultural creativity, he believed, was possible only in the city-state: the Greek polis, the medieval cities, and the Renaissance cities of Italy. The enemies of culture were democracy, centralization, materialism, and the geographically extended state. He scorned specialization in historical writing and avoided meetings of professional historians, which he observed were attended by historians “in order to sniff each other like dogs.”

Burckhardt was unabashedly elitist and aristocratic in his values. The Renaissance he viewed as an elite culture. While skeptical of the claims of orthodox Christianity, he was a Christian in ethical practice and hoped that a religious rebirth would rescue Europe from decadence and disaster. Both socialism and materialism he held to be evidences of cultural decline. He detested militarism and the pursuit of power. He believed that the world of the nineteenth century was moving inexorably toward a socialist tyranny. He saw the French Revolution and the Paris Commune as the beginning of this tragic development.

The rediscovery of Burckhardt in the Anglo-Saxon world immediately following World War II had a marked influence on the revival of conservative thought. The publication of Force and Freedom (1943), with its brilliant and trenchant introduction by James Hastings Nichols, was of decisive importance. Alexander Dru’s selection, translation, and editing of Burckhardt’s letters (1955), and his long and appreciative introduction, were also very important. Werner Kaegi’s scholarly editions of Burckhardt’s works, together with his biography (Burckhardt, eine Biographie, 1947–82), were essential to Burckhardt scholarship. The translation by Moses Hadas of Burckhardt’s Age of Constantine the Great (1949) and Harry Zohn’s translation of Judgments on History and Historians completed the sources of influence.

Further Reading

Thomas Albert Howard, Religion and the Rise of Historicism: W. M. L. de Wette, Jacob Burckhardt, and the Theological Origins of Nineteenth-Century Historical Consciousness

John Roderick Hinde, Jacob Burckhardt and the Crisis of Modernity

Richard Sigurdson, Jacob Burckhardt’s Social and Political Thought

This entry was originally published in American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia, p. 100.