A type of totalitarianism, fascism arose out of the chaos that followed World War I (1914–18), when economic hardship, thwarted idealism, and bruised national pride combined to radicalize European politics. The fascist era in Europe is usually dated from 1922, when Mussolini came to power in Italy, to 1945, when Hitler’s Nazis were crushed at the end of World War II. But it was an international movement of somewhat longer duration, finding supporters throughout the European continent as well as in Britain, North America, and South America.

The word “fascism” was coined by Mussolini. It derives from the Latin fasces, referring to the bundle of rods and projecting ax-head that in antiquity was carried before Roman consuls as a sign of state authority. The rods symbolized social unity; the executioner’s ax, firm political leadership. (Use of the fasces as a political symbol is not restricted to fascist parties: in America fasces adorn the wall behind the Speaker’s platform in the U.S. House of Representatives and are stamped on the so-called Mercury dime.)

As the British philosopher Roger Scruton has pointed out, fascism is characterized more by a common ethos than a consistent political philosophy. Nevertheless, around Italian fascism, German Nazism, and Spanish falangism clustered several distinctive traits. Fascist parties showed implacable hostility toward parliamentary democracy, egalitarianism, and the values of the liberal Enlightenment; and because fascists viewed the world as a Darwinistic jungle in which only the most militant could survive, they tolerated no domestic competition. To secure control of a people, fascists advocated one-party rule by an elite, the use of secret police to eliminate dissent, strict control over the media, and unquestioning obedience to a charismatic leader. To incite enthusiasm for their rule they made appeals to youth and promoted a cult of violence. Nazi calls for organic social harmony (in the name of das Volk), militaristic chauvinism, and Lebensraum (living space) appealed to the popular imagination as did the use of vivid symbols, torchlight parades, uniforms, and military discipline to express unity in a fragmented age.

Hitler’s Brown Shirts and to a lesser extent Mussolini’s Black Shirts added two further doctrines to these traits: a barely disguised hostility to Christianity, whose traditional forms they intended eventually to stamp out, and anti-Semitism, which led to the state-sponsored execution of between five and six million Jews.

Despite fascists’ harangues against democracy and egalitarian economic arrangements, they were able to win massive popular support in Europe before the 1940s, a fact that has vexed many students of the movement. Moreover, to the embarrassment of the avant garde, a number of modernists flirted with fascism at one time or another. In Britain, for example, Ezra Pound, George Bernard Shaw, William Butler Yeats, T. S. Eliot, and Wyndham Lewis were drawn to certain fascist ideas. Influential antimodernist Catholics such as G. K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, and Roy Campbell were also receptive to fascist notions when the movement was still young. Indeed, for a brief time, fascism enjoyed a radical chic in British high society. But Eliot, Lewis, Chesterton, Belloc, Campbell, and others recoiled from Il Duce and Der Fuhrer when they recognized fascism’s nihilism and hostility to the West’s historical religions.

The fact is, fascism never took root on American soil and was never an attractive alternative to the right.

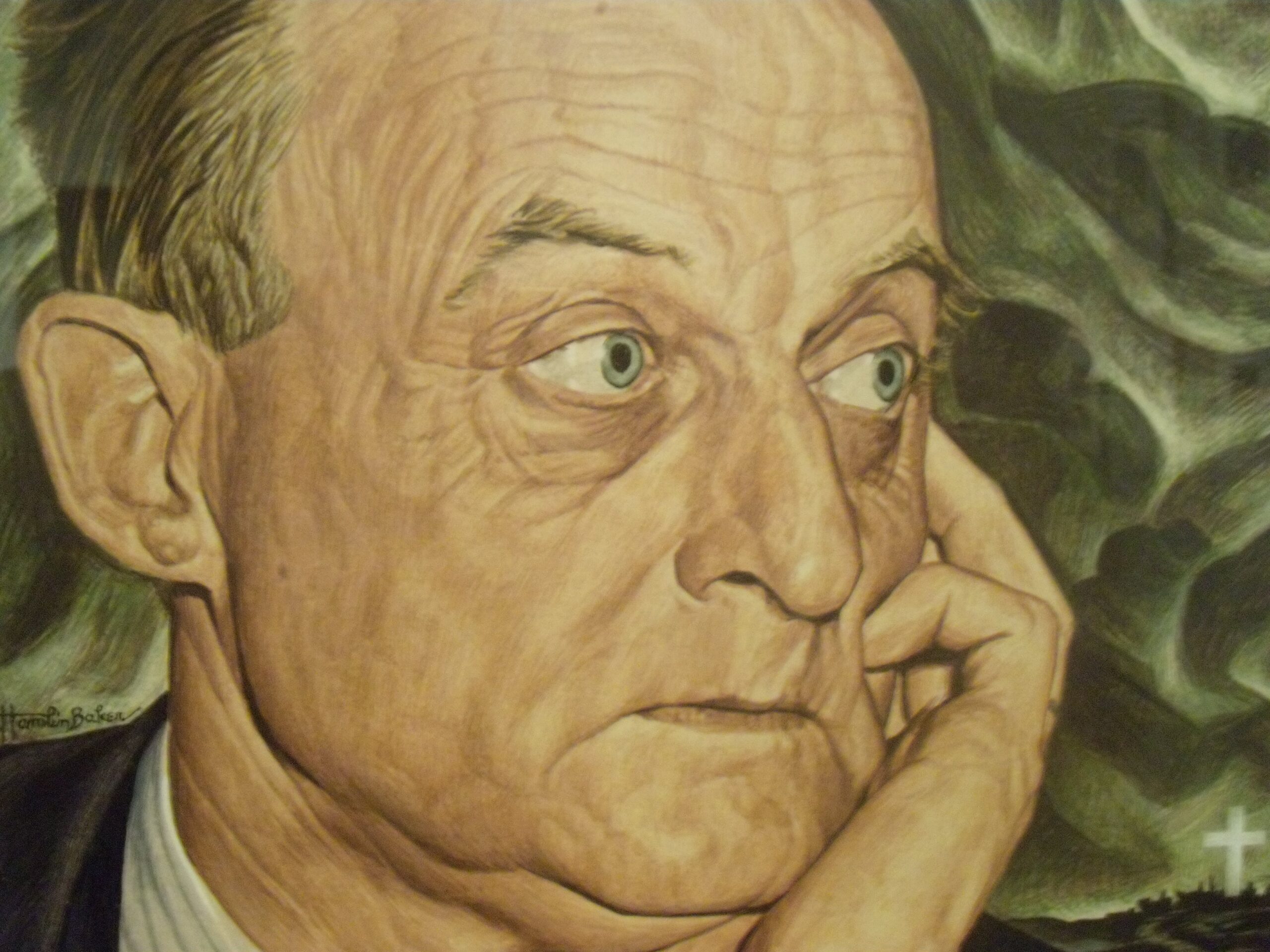

Scholars have long debated the extent to which fascism was the outgrowth of the left or right. Since the 1930s, Marxists, following Trotsky, have tried to make the case that fascism was the inevitable result of the structural crises that wracked latter-day monopoly capitalism. But even Trotsky himself recognized that “Stalinism and fascism, in spite of a deep difference in social foundations, are symmetrical phenomena. In many of their features they show a deadly similarity.” Another influential writer, the Hungarian-British writer and philosopher Arthur Koestler, abandoned the Communist Party in the late 1930s and traced the similarities between Stalinism and Nazism in novels such as Darkness at Noon (1940) and Arrival and Departure (1943)—“perhaps the best analyses of the totalitarian mind ever written,” according to Bernard Crick.

Indeed, many scholars see not just Stalinism but Marxist-Leninism as a totalitarian cousin to fascism. It would thus be misleading to place Marxism and fascism at opposite ends of the left–right political spectrum. Mussolini, after all, began his political career as a socialist, and his mature fascist doctrines bear the unmistakable stamp of Marx, Sorel, and Lenin. Other fascist leaders learned, in turn, from Mussolini: for Valois in France, Franco in Spain, Mosley in Britain, Degrelle in Belgium, Hitler in Germany, and their followers, “Nationalism plus Socialism equals Fascism,” a formula that reveals fascism’s affinity with the left. Even the word “Nazi” has a leftist connotation, derived as it is from the full party title, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei). Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn summarized the relationship between fascism and Marxist-Leninism by referring to them as “socialism national and international.”

The historian Stanley Payne wrote that fascism’s ties to the traditional right were frequently tenuous. In Europe, the marriage between fascists and conservatives during the 1920s and 1930s, when it occurred, tended to be one of convenience, not of love. Often such political alliances were forged to jettison indecisive liberal institutions and to combat what was perceived to be the common enemy—Bolshevism. The alliance was bound to be temporary once fascism’s full revolutionary agenda was revealed. One radical difference between fascists and traditionalist conservatives turned on religion. For the former, Christianity was anathema since it provided a source of moral criticism prior to and higher than the state; consequently, Nazi leaders wanted eventually to eradicate Christianity and replace it with a pagan pseudo-religion wholly subservient to the state.

There were pockets of fascist sympathy and collaboration in America prior to and during World War II, issuing mainly from anti-Semitic and extremist populist sentiment. Gerald L. K. Smith, Charles Eugene Bedaux, and T. Lothrop Stoddard were among the most prominent. Historians have also identified protofascist tendencies in politicians like Huey Long, who attempted to abolish the power of local government in Louisiana. Mistakenly, Charles A. Lindbergh’s antiwar speeches for the America First Committee were branded pro-Nazi, yet his goal was not to promote Hitler’s programs but to urge America to stay out of a costly European conflict: in this he was no different from countless American isolationists. The fact is, fascism never took root on American soil and was never an attractive alternative to the right. Its ethos was too alien to American political traditions and values to win wide support. The American Nazi Party, founded in 1958 by George Lincoln Rockwell, probably never numbered more than a hundred members at a time.

Unfortunately, the term “fascist” has been widely used by student radicals since the Vietnam War era to attack college administrators and (mostly Republican) politicians. But such use of the term is not only unfounded but irresponsible since it blunts our understanding of what fascism historically entailed.

Further Reading

Victor C. Ferkiss, “Populist Influences on American Fascism,” Western Political Quarterly

James A. Gregor, The Ideology of Fascism

Alastair Hamilton, The Appeal of Fascism: A Study of Intellectuals and Fascism, 1919-1945

H. R. Kedward, Fascism in Western Europe, 1900-1945

Stanley Payne, Fascism: Comparison and Definition

Robert A. Pois, National Socialism and the Religion of Nature

This entry was originally published in American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia, p. 294.