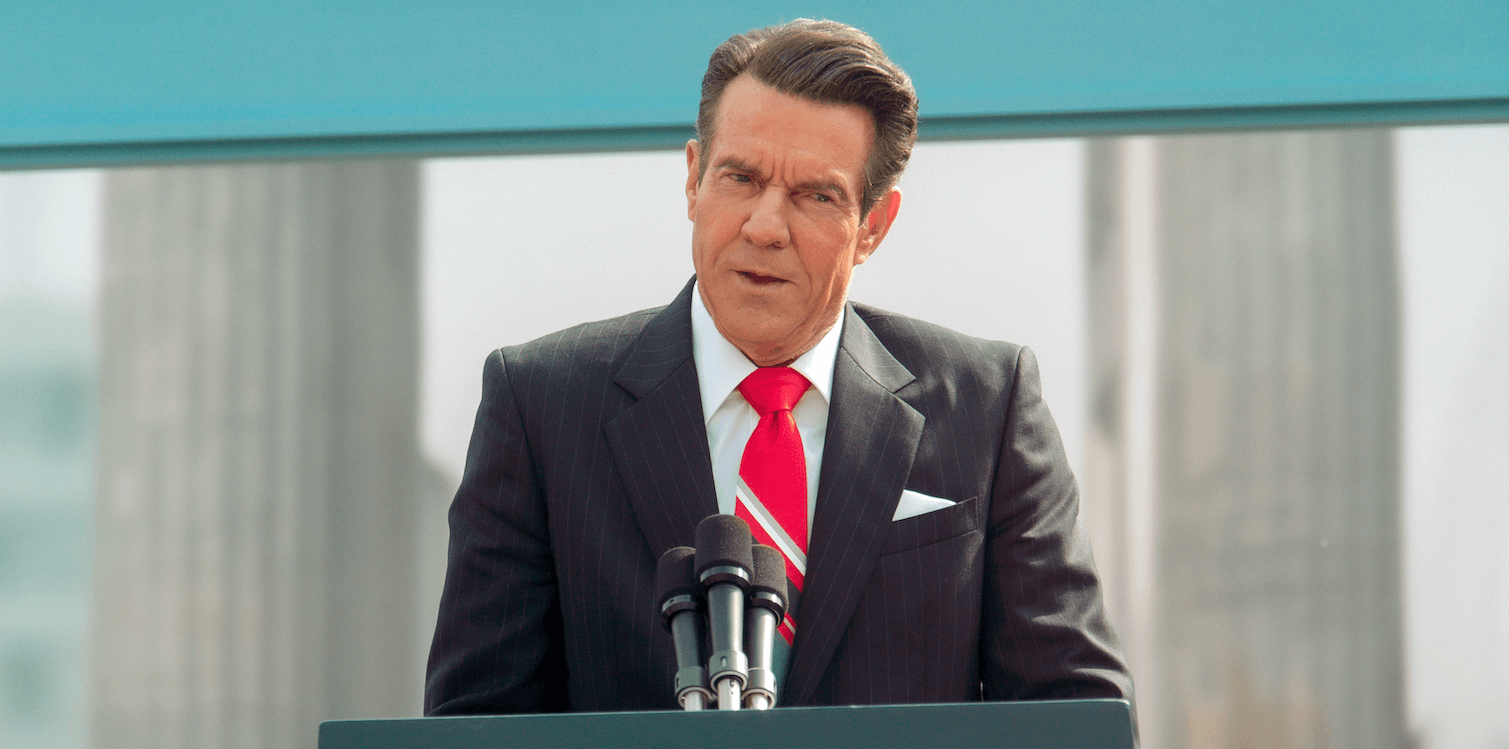

Ronald Reagan is back on the big screen, this time with a look back at Morning in America rather than Bedtime for Bonzo. The new film Reagan, starring Dennis Quaid as the fortieth president, hits theaters as the 2024 presidential campaign kicks into high gear.

The current race is being conducted in Reagan’s shadow even though a baby born the day he left office would now be old enough to run for president. Conservatives have been debating whether it is time to move past the old Reaganite consensus. Liberals, and Republicans disenchanted with their three-time standard-bearer former President Donald Trump, are trying to rebrand Kamala Harris’s Democrats as the new party of Reagan.

Democrats have celebrated their past presidents for decades after the fact long before Republicans venerated Reagan. Pictures of Franklin D. Roosevelt adorned the mantles of rank-and-file Democrats of my grandparents’ generation well into the 1980s. Bill Clinton is still dragged out of mothballs to address the Democratic National Convention every four years, avoiding a #MeToo cancellation. Jimmy Carter has been rehabilitated. Family members ritually denounced Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s Trump endorsement because it ostensibly sullied the memories of his father and uncles Ted and John F. Kennedy.

Meanwhile, Republicans discarded Richard Nixon and George W. Bush quickly after their presidencies ended badly. Republican nominees from Bush all the way to Mitt Romney feel out of step with today’s GOP, with hundreds of their campaign alumni now quadrennially endorsing Democratic presidential candidates. George H. W. Bush and Gerald Ford were respected, but not held up as examples for future Republican leaders. Herbert Hoover did get to speak at every Republican National Convention from the time he was voted out of office during the Great Depression until he died, but to little fanfare.

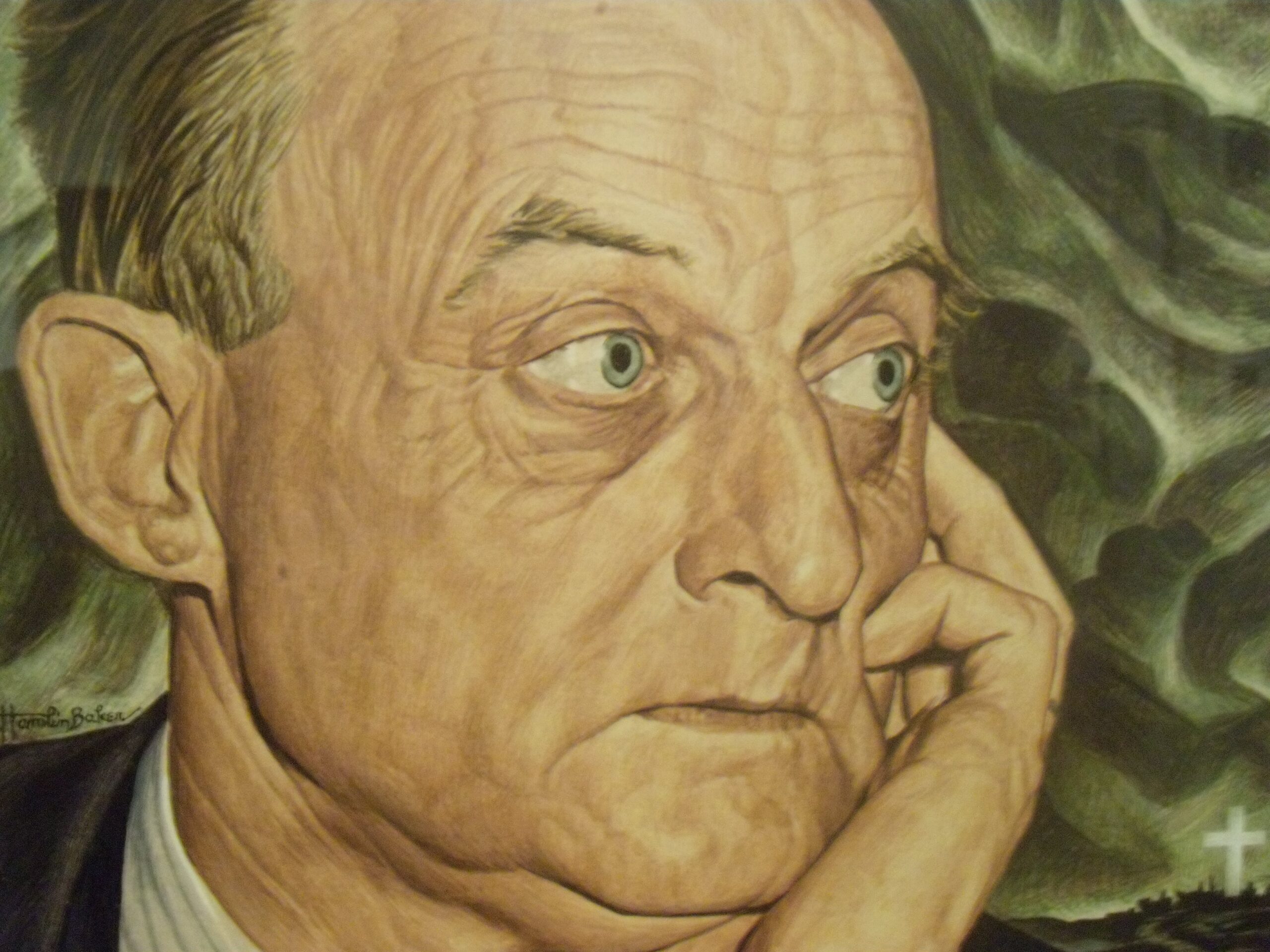

Reagan is unique in this respect because he is the only modern Republican to boast achievements that sit alongside those of the New Deal or Great Society. “[E]very American president will be remembered in history with but a single sentence,” Pat Buchanan declared at the 1992 GOP convention in his famous “culture war” speech. “George Washington was the father of his country. Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves and saved the Union. And Ronald Reagan won the Cold War.” (Something to remember when prominent conservatives lament that the Reaganites have been replaced by Buchananites in the Trump era—Buchanan actually served in the Reagan White House.)

In addition to the Cold War, Reagan helped steer the United States’ economy out of stagflation. It took forty-one years for inflation to become a major economic and political problem again. This accomplishment gets some play in Reagan, but the battle with the Soviet Union—the film is based on Paul Kengor’s book The Crusader: Ronald Reagan and the Fall of Communism, after all—takes center stage.

That’s not to say that the movie doesn’t try to be comprehensive. It shows scenes from Reagan’s childhood and stretches back to acting days. As Reagan’s career in Hollywood declines, his political interests deepen. As president of the Screen Actors Guild, he has his first run-ins with communists. Reagan’s budding anti-communism and union leadership bores his first wife, the actress Jane Wyman, to such an extent that it leads to the dissolution of their marriage. But the same interests also attract the love of his life, Nancy.

If anything, Reagan is reminiscent of the Sopranos’ prequel The Many Saints of Newark in that any omission—for example, how much Reagan’s commitment to individual freedom extended beyond the struggle against Soviet communism—is a direct product of how much the movie tries to do. The greatest hits are all there, but they can’t all be played at the same length.

Dennis Quaid is believable as Reagan (a police officer I overheard discussing the film at the Republican convention in Milwaukee agreed). Jon Voight is also entertaining narrating Reagan’s life story as a KGB agent explaining the downfall of the Evil Empire. Despite the power of Voight’s performance, however, that plot device does at times get old. Reagan’s life story is compelling on its own, and the insertion of fictional characters—Edmund Morris employed the same technique in his officially sanctioned memoir Dutch—is unnecessary.

In his farewell address to the nation, Reagan took issue with the nickname “the Great Communicator.” He said that he was actually a communicator of great things. One of the best parts about the Reagan movie is that it equally showcases his steadfast anti-communism and his aversion to war, his willingness to take political risks both to enhance American military might and engage in diplomacy that could save millions of lives. “Peace through strength” remains a popular slogan in Republican circles, but strength was a means to achieving peace rather than a goal in itself—a point lost less on Trump than on some self-styled neo-Reaganites of the past three decades.

Nevertheless, there are few figures in today’s GOP who simultaneously speak in Reagan’s idealistic terms without subordinating foreign policy entirely to idealism, like a hawkish answer to the Carter administration the Gipper replaced.

As someone who has a strong attachment to Reagan and the period of time when he was president, I find the movie hits the right emotional notes. I worry that some of that will be lost on younger viewers who do not share that nostalgia, many of them conservative.

Critics can debate the movie’s greatness. It indisputably communicates great things.