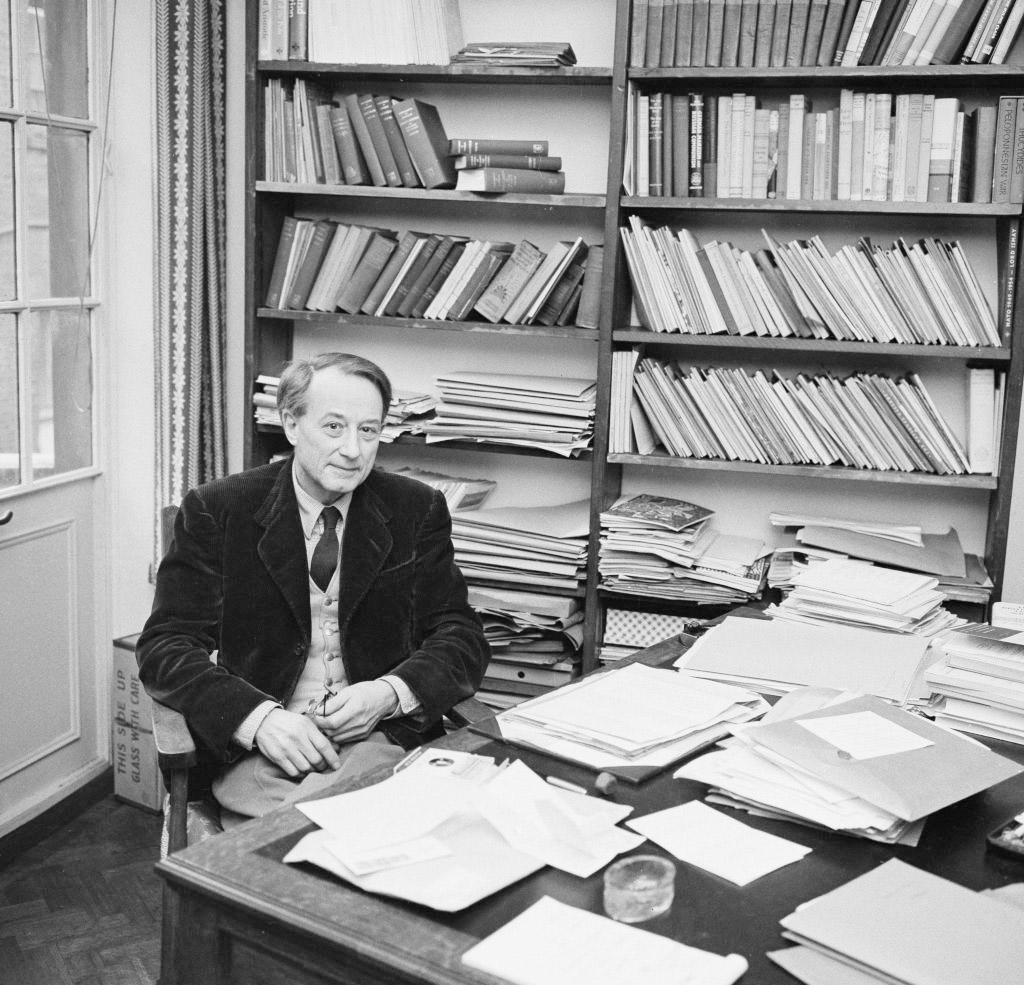

Timothy Fuller of Colorado College is one of the world’s foremost scholars on the work of the British philosopher Michael Oakeshott. Fuller was also a friend of Oakeshott’s for the last sixteen years of the latter’s life, for a time shared an office with him, and later took frequent trips to England to converse with him. As such, this collection of Fuller’s essays (many previously published) on Oakeshott is a welcome addition to the ever-increasing volume of secondary literature on the thinker.

The book opens with a charming reminiscence of Fuller’s various encounters with Oakeshott, beginning when in 1959, as a student at Kenyon College, Fuller first read Oakeshott. He recalls Oakeshott “smoking continuously” as he repeatedly revised his papers for the History of Political Thought seminar at the London School of Economics and recounts how they would go out to eat at Luigi’s or Mon Plaisir afterward. When Fuller visited Oakeshott at his Dorset cottage, he saw him drive his 1958 MGB “at excessive speed through the hedgerows” and learned that he was a skilled cook and gardener.

This book consists of sixteen essays by Fuller, arranged in chronological order. The first essay after the introduction is previously unpublished and is also the first of Fuller’s writings on Oakeshott. In it, Fuller takes up Oakeshott’s concept of “modes” of experience, as described in Oakeshott’s first book, Experience and Its Modes (1933). (This idea is in the background of all of Oakeshott’s later work.) In brief, a mode is the whole of experience viewed from a partial, abstract perspective. Science, for instance, is the mode that views experience through the lens of measurable quantity; practice is the mode that understands experience as the continual attempt to replace what is with what ought to be; and history is the mode that views the present world as a repository of evidence for a world gone by.

Now every mode, but in particular science and practice, is prone to hubris, to asserting that its partial view of the world of experience is complete and fully satisfactory. For example, “rationalism in politics,” a more famous concept of Oakeshott’s, is a criticism of attempts to treat practical life as though it were a part of the world of science.

The essays move on to another important concept for Oakeshott, that of “civil association,” to which he devoted much of his 1975 work On Human Conduct. By civil association, Oakeshott meant a group of people associated not by pursuit of a common end (as in an “enterprise association” such as Google, the New York Yankees, or the American Cancer Society) but by subscription to a common body of law and recognition of an authority which is that body’s custodian. In an essay entitled “Authority in the Individual in Civil Association: Oakeshott, Flathman, Yves Simon,” Fuller compares the ideas of Oakeshott on the source of civil authority with those of the American political scientist Richard Flathman and the French philosopher Yves Simon. Fuller finds Oakeshott to be flanked on one side by Flathman’s “resolute irresolution” about using authority. Of Flathman, Fuller writes:

Like Locke, Flathman would have it two ways at once: the threat of the appeal to heaven will help keep the authorities skittish about the exercise of authority, and most people will perhaps find it to their advantage to be governed by those who are skittish about governing.

On Oakeshott’s other side is Simon, who, working in the Thomistic natural law tradition, finds authority to be tasked not merely with preserving civil order but also with moving individuals towards their supreme good, as far as it is possible to do so. Oakeshott, then, occupies a middle ground, neither being “skittish” about authority like Flathman nor assigning it any role beyond maintaining order.

The next essay is the text of the eulogy that Fuller delivered at the London School of Economics’ memorial service following Oakeshott’s death in 1990. In it, among other things, we learn of Oakeshott’s love for the American West, his non-utilitarian understanding of the purpose of higher education, and his profound influence on his students. On the last point, Fuller writes, “I have not personally known anyone who could feel the beauty of youth more intensely, even at the end of his days, than Michael.”

The chapter entitled “Michael Oakeshott’s Political Thought” intriguingly begins with an extended discussion of his religious studies. This is an aspect of Oakeshott’s interests that, after the early 1930s, he was “reticent” to discuss, but Fuller tells us that his study of theology was a lifelong pursuit. Oakeshott, he writes, “thought that St. Augustine enjoyed the greatest religious imagination within our tradition and after him Pascal.”

“The Poetics of Civil Life” discusses the foundations of civil order. Along the way, it makes an important point against anarchism. Anarchists argue that any justification for the existence of government relies on the assertion that government officials are qualitatively better than the rest of us when it comes to making practical decisions about social matters. But that is nonsense: the justification for having an umpire in a baseball game is not that the umpire understands baseball better than the players or that he is infallible or even better than the players at determining what is a ball and what is a strike, but merely that it is desirable to have someone whose pronouncements on the matter are authoritative and final. Both the pitcher and the batter may, in general, be better judges of what is a ball and what is a strike than the umpire is. But clearly, given that they are not disinterested parties about the distinction, they will often disagree. So there must be someone possessed of an office with the authority to decide “ball or strike,” or the game cannot proceed.

As Oakeshott puts it: “The civil association requires someone to occupy an office of authority that is acknowledged as the source of authoritative pronouncements . . . the occupant of an office like this is not privileged with special insight or knowledge.” Oakeshott also notes that the laws of civil association “are not the rules of a game,” but that does not mean they do not bear many similarities to the rules of a game. Furthermore, there must be a way to decide where the strike zone is, whether there is such a thing as an “infield fly rule,” and, if there is, when it applies. Such decisions require an entity authorized to make them.

In the essay “On the Character of Religious Experience,” Fuller returns to the concept of Oakeshott’s modes, but in ways that sometimes seem at variance with Oakeshott’s thought. Fuller writes, “So far, no ‘what is’ has ever ended challenges from further thoughts of what ought to be.” While that is true, it is beside Oakeshott’s main point, which is that such a happening would dissolve the practical mode since its primary presupposition is that the existing world is in some sense unsatisfactory and requires practical action to render it more satisfactory. (On this point, Oakeshott is remarkably like Ludwig von Mises, who noted that action requires “felt unease.”) So long as there is a world of practice, it is not merely that “not yet” have we ever found our current situation completely satisfactory, but that with certainty we never will. Fuller follows up his statement with a quote from Oakeshott that makes exactly this point, that “challenges from further thoughts of what ought to be” constitute the world of practice; they are not a contingent aspect of it that might one day disappear.

I have a similar puzzle about another proposition of Fuller’s, to wit: “So long as the future is an essential element in practical appraisal, coherence has to elude us.” Here, the first three words are what trouble me: it is not as if the future could cease to be an essential element in practical appraisal. As mentioned above, the world of practice presupposes understanding experience as consisting of a somehow less-than-satisfactory current situation that ought to be replaced by a more satisfactory future situation. Appraisal without an eye to the future is not something that might unexpectedly “crop up” in tomorrow’s practical activity: instead, it would mean we had left the world of practice behind.

In another chapter, Fuller takes John Stuart Mill to be a representative specimen of Oakeshott’s ideal type of the “politics of faith”—in brief, approaches which believe that politics is the path to an earthly paradise. Oakeshott, in contrast to Mill, recognizes the politics of faith as an enduring pole of modern European politics but is himself more inclined towards the “politics of skepticism.” Oakeshott finds no foundation for the claims on the part of practitioners of the politics of faith that history exhibits regular moral and political progress “apart from a strong commitment to them among the intellectual elite.”

In an essay on historicism, Fuller finds Oakeshott, along with Hans-Georg Gadamer, to occupy a salutary middle ground between R. G. Collingwood’s embrace of historicism and Leo Strauss’s complete rejection of it. As Fuller sagely points out, if Collingwood is claiming to “re-enact” the thought of, say, Plato, while also rejecting any supra-historical truths, he is certainly not re-enacting Plato’s claim to have actually experienced a transcendent reality. On the other hand, the variety of historicism Strauss focuses his attacks upon is, per Gadamer, “naive historicism”: we can accept the existence of transcendental truths while at the same time recognizing that our necessarily limited understanding of such truths is historically conditioned.

In “Taking Natural Law Seriously,” Fuller examines Ronald Dworkin’s 1977 book Taking Rights Seriously and concludes that the eminent legal theorist “would appear . . . to be intent upon transforming the commitment to the rule of law into a commitment to social engineering.”

For Oakeshott, in contrast, a judicial authority, under the rule of law, cannot “regard itself as the custodian of a public policy or interest in favor of which . . . to resolve this disputed obligation.” Fuller contrasts both Dworkin and Oakeshott with the natural law theorist John Finnis, who “seeks to pass between the normative speculations of . . . utilitarian theorists, and the stark procedure of the pure rule of law.”

Along the way, he aptly quotes Finnis on why utilitarians cannot do the calculations that they claim are at the core of their ethics: the utilitarian’s “imaginary perspective, as a God-like figure surveying possible worlds and choosing the world that embodies greater good or lesser evil, is a perspective that is simply not open to human practical reason.”

An unfortunate aspect of these essays is that many of them are intended as introductions to the thought of Oakeshott, and thus there is a high degree of repetitiveness in them. For instance, a favorite story of Oakeshott’s, of the Chinese wheelwright unable to pass his learning on to his son, is told no fewer than three times, and Oakeshott’s notable quote on politics being the “pursuit of intimations” is repeated as often. To reuse such illuminating passages in essays published years apart in different outlets is understandable, but a little judicious editing might have relieved some of the repetition once these essays were collected together.

Despite this flaw, this collection of essays is an excellent introduction to Oakeshott for the newcomer. Those more familiar with Oakeshott should still find it packed with insights into the thinker that will make reading it worthwhile, as it certainly was for me.