I have been trying to write something about The Zone of Interest, Jonathan Glazer’s Oscar-winning film about Rudolph Höss (played by Christian Friedel), the commandant at Auschwitz, for months, ever since I saw it for the first time. That was on October 13, 2023, less than a week after brutal massacre of Israelis perpetrated by Hamas on October 7. I walked into the screening at the New York Film Festival with more than a little trepidation. Was a film about one of the most diligent perpetrators of the Holocaust really what I wanted to see at such a time?

The experience was overwhelming, and quite different from what I anticipated. I had heard something about the film, so I knew more than just its subject. I knew that it was primarily about Höss’s personal and professional life rather than, in any direct way, his crimes. I knew that Glazer used hidden cameras to capture much of the interior life of the Höss home and give the audience the experience of being a fly on the wall, as if they are watching security camera footage. I knew that the soundscape made an outsized contribution to the tone of the film (which ultimately won an Academy Award for Sound Design in addition to the award for Best International Feature) and that the sounds of the camp—screams, shots, the crematoria belching flames—underscored the mundane scenes of family life to ominous effect.

What I didn’t anticipate was what Glazer’s design added up to. Audiences watching a horror film, if they are knowledgeable about the genre, will recognize its tropes; knowing that they are watching a horror film, and that the characters they are watching on screen are therefore in a horror film, they will get a powerful urge to scream at the screen: “Don’t laugh at that creepy guy warning you to stay away! Don’t split up to search the area more quickly! Don’t go down to the basement! Don’t you know you’re in a horror film?” The audience identifies with the poor saps about to be eaten by the eldritch horror but is in a position of superior knowledge to the film’s victims simply by virtue of knowing how these films work, and is satisfyingly infuriated by the sheer ignorance of the characters on the screen.

The Zone of Interest is a species of horror film, focused almost exclusively on engendering that feeling, but its tricks are deployed in a highly novel direction. Though it is a horror film, the horror—the mass murders and routine tortures of Auschwitz—is never shown. The audience must bring not only knowledge of the genre but also specific knowledge of the Holocaust to understand what the film is even about. The poor saps the audience identifies with, meanwhile, are not the victims of the horror, but its monstrous perpetrators and enablers. There are other characters, including inmates and even one servant girl who performs small acts of kindness for those inmates, but we never get a clear fix on any of them, never get to know them as people. It is the members of the Höss family that we watch going about their daily lives, and for a full 105 minutes we want to scream, “Don’t you know you’re in a horror film?” But they seem blissfully unbothered by the monstrousness of the lives they are living, almost as if they didn’t know.

Of course, both in reality and in the film, the Höss family did know what was happening in Auschwitz, as intimately as anyone on earth. This is not a film about people who could claim they “had no idea” what was happening behind the walls of the most infamous camp in the Nazi archipelago of extermination. In one of the earliest scenes in the film, Höss meets with engineers who have designed a more efficient crematorium that could operate continuously, processing vastly more corpses than the camp’s current setup would allow. The scene is there to remind us of the scale of the crimes perpetrated there, and to show not only Höss’s but the engineers’ satisfaction at finding a way to scale up those crimes further.

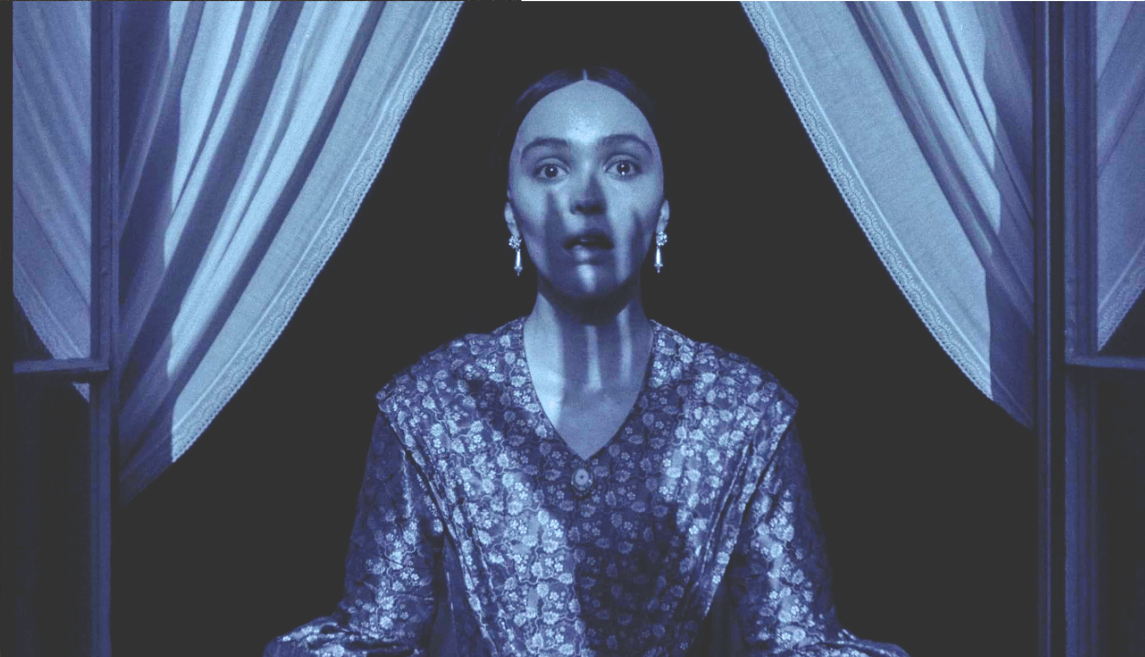

Höss’s wife, Hedwig (played by Sandra Hüller), is fully aware of her husband’s role and proud of all that he has achieved, and she takes her own pride in the little slice of paradise she has made of their home, with its elaborate gardens and its backyard swimming pool. Her mother is even prouder; she used to be a cleaning woman for a Jewish family, and now look how far up in the world her daughter has come. Members of the Höss family know how their comfort has been purchased; Hedwig gratefully receives a fur coat that once belonged to an inmate, and, after finding diamonds hidden in toothpaste, comments on the ingenuity of the Jew who hid them there and suggests that they should order more toothpaste, because you never know. Her comfort extends to the power over life and death: when she is frustrated with a Polish servant, Hedwig snaps at the girl that if she doesn’t shape up, her husband could have her ashes spread in the garden. Though she does not carry out that threat, we later see an inmate spreading human ashes as fertilizer in that very garden.

This is not a film, in other words, about people who are ignorant of the horror in which they are complicit. Nor is it a film about people who merely turn a blind eye to a horror, compromising with evil and pretending they aren’t tainted by it. Höss’s family doesn’t just approve of the benefits reaped from his efforts but endorses the efforts themselves. Yet even that approval doesn’t come in the guise of obvious monstrousness. Their antisemitism is casual, but it isn’t expressed with any especial ferocity. Hedwig’s mother wonders at one point whether her old employers might be on the other side of the wall, but not because she is concerned for them; she surmises that they were up to some Judeo-Bolshevik mischief all along, and so they deserve whatever they’re getting. As for the children, we never learn what they think, but we do know what they know. At night they gaze out of their bedroom windows at the flames. As they play with their toys, we hear their father on the other side of the wall ordering an inmate to be drowned for fighting over an apple. At another point, we see them playing with human teeth.

These are intrusions, though, into a landscape that is portrayed as normal, even aggressively so. The Höss family has its problems, but they are those of a normal family. Rudolph is an awkward nerd with a ridiculous haircut, but he’s also a doting father. Hedwig is a petty gossip but also a diligent hausfrau. Rudolph has his vices—he receives sexual services from a servant (clearly intimated, but not shown)—but he is discreet about them, and he is plainly devoted to his work. The main plot point of the nearly plot less film is when Höss is kicked upstairs to become an inspector of all the camps rather than a single camp’s commandant, and Hedwig refuses to leave her home or move the children to join him, declaring that their home is their Lebensraum. Her husband is startled by the idea of being apart but acquiesces to her logic. By and large they seem a happy couple, sharing little marital jokes (Hüller’s porcine snort is alarming, but that’s because it’s authentic, not at all overplayed), and genuinely caring for and appreciating each other. It is precisely this normalcy that makes this a horror film, because we know that these normal people are actually among the greatest of history’s monsters.

The last moment we see the couple share together is a perfect synecdoche for the tone of the film. Rudolph calls his wife from Berlin late at night after a big party. He has just learned that he will be brought back to Auschwitz to oversee the destruction of Hungarian Jewry, a big job that they feel requires a capable hand. Naturally, he finds this recognition of his capabilities gratifying. Weary but happy for him, Hedwig asks if he enjoyed the party. Not really, he replies; it’s not his kind of affair. He occupied himself by calculating how much gas it would take to kill everyone there—a tough problem given the ballroom’s high ceilings.

Our flesh crawls at this ease with horrible actions both because of our background knowledge and because of the doom-laden underscoring. Yet none of it is played as horrible, nor archly as blackly comic satire. It’s played entirely straight. Why tell this story in this way? Why make us live with the Höss family and identify with their normalcy when we know of their active embrace of evil?

It’s tempting to see this approach as a cinematic illustration of Hannah Arendt’s diagnosis of banality as central to the Holocaust’s evil: that what the Nazis did most paradigmatically was to get ordinary people to pursue ordinary ends within their view— career advancement for themselves, bureaucratic efficiency for their organization—to the most monstrous ends for the organism as a whole. If that’s the diagnosis, then the cure, presumably, is the escape from the realm of banal virtues such as diligence into the realm of higher values, to a conscious determination to care about the purpose an organization serves and not just our role within it. This doesn’t fit the Höss case as depicted in the film, though (nor did it fit Eichmann’s case, which prompted Arendt’s comments about banality, as further investigation revealed Eichmann to have been an enthusiastic antisemite). Höss is trying to do a good job and get ahead, yes, but he made love to his employment because he believed in it. He was, in his horrible way, an idealist, even in his and his wife’s pursuit of a comfortable, “normal” life.

In Glazer’s film, it turns out that evil itself can be banal, can be embraced wholeheartedly without making the people clasping evil to themselves obviously monstrous in any way, unless we know what they are about. The effect of intimacy with such normal-seeming monsters is to turn our gaze inward—or so it was for me. What am I doing that is monstrous, fully cognizant of its monstrosity but convinced that that monstrousness is justified? How have I grown comfortable with monstrousness? And how badly have I been deformed—how much of a monster have I become—as a result? These are the questions I walked out of the theater asking myself.

I had never seen a Holocaust film that produced such an effect in me as a viewer. I’d seen numerous films about the experience of survivors, both during and after the Holocaust, and am particularly fond of films that depict these people simply as people with the normal range of human traits to show that the mass murderers didn’t discriminate in whom they killed or whom they spared. I’m fond of quoting Angelica Huston in Enemies, A Love Story when she upbraids her husband for coming to her to complain about the problems he’s having with his other two wives: “Were you always like this? Or did the war do it?” I’d seen fewer films focused on the perpetrators, because, I felt, they tended toward sentimental narratives of unearned redemption. But The Zone of Interest is the first Holocaust film I’ve watched that seeks, and achieves, the effect of making me feel that the worst mass murderer is only a little different from myself.

So I planned to write an essay about that novelty. I read Rich Brownstein’s comprehensive index of Holocaust films, appropriately titled Holocaust Cinema Complete, to make sure I hadn’t missed an important antecedent; it appeared that I hadn’t. I read Martin Amis’s novel upon which the film is nominally based to see whether he had undertaken the same task in fictional form, but he hadn’t; the Höss of Amis’s novel is a loathsome and pathetic creature, despised by his wife and by the reader. My argument, as I originally conceived it, would be some thing to the effect that the film marked an important evolution in the meaning of the Holocaust: with the passage of time, the dwindling numbers of living survivors, and the loss of moral confidence in the West, Holocaust films have transitioned from warnings against being a bystander to evil to fears of becoming a perpetrator.

Then, at the Academy Awards, Jonathan Glazer explained in his acceptance speech precisely what he intended his film to mean, and whom he thought needed to be warned against becoming a perpetrator, by connecting the Holocaust with October 7 and its aftermath:

All our choices were made to reflect and confront us in the present—not to say, “Look what they did then,” rather, “Look what we do now.” Our film shows where dehumanization leads, at its worst. It shaped all of our past and present. Right now we stand here as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many innocent people. Whether the victims of October the 7th in Israel or the ongoing attack on Gaza, all the victims of this dehumanization, how do we resist? Aleksandra Bystroń-Kołodziejczyk, the girl who glows in the film, as she did in life, chose to. I dedicate this to her memory and her resistance.

This statement, as Glazer surely must have expected, ignited a firestorm of criticism. Many saw the speech as an act of Jewish self hatred, in part because of its confused phrasing (Glazer was clearly “refuting” Israel for “hijacking” his Jewishness, not “refuting” his Jewishness itself, whatever that might mean), but more broadly because they saw self-criticism as giving aid and comfort to a deadly enemy. Most notably, László Nemes—the director of Son of Saul, another film set at Auschwitz (about a member of the Sonderkommando, the Jewish inmates charged with disposing of the bodies from the gas chambers) that also won the Academy Award for Best International Feature—praised Glazer’s film but denounced the director’s speech for having “no understanding of history and the forces undoing civilization” and for being little more than “talking points disseminated by propaganda meant to eradicate, at the end, all Jewish presence from the Earth.”

I had a very different reaction to the speech myself. In part, this was because when I saw the film that first time, back in October, I already felt it was implicitly about Gaza. This wasn’t because what was going on behind the wall that the terrorists breached on October 7 was in any way comparable to what went on in the Nazi death camps, nor because Israel bore a comparable level of responsibility for the suffering there to that which the Nazis bore for their crimes. But the wall itself was an expression of a larger attitude of moral indifference that had come to predominate Israeli attitudes toward Palestinians. In his speech, Glazer described his film as a warning about where that kind of indifference could lead, and, even in the face of genocidal violence perpetrated by Hamas against innocent Israelis, I still felt the force of that warning.

Of course, if there is anything more banal than evil, it is moral sermonizing by the winners of Academy Awards. Glazer is a filmmaker, not a foreign policy analyst, so the interesting question from my perspective is not his assessment of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians but his assessment of his own film. On my first viewing, I already had the experience, unprompted by his sermon, of being impelled to reflect and confront myself in the present. I wonder whether Nemes or anyone else who praised the film while criticizing Glazer’s speech for Jewish self-hatred had truly absorbed what they had seen. But Glazer’s understanding also struck me as questionable. He described the Polish girl—whose role seemed enigmatic but peripheral to me when I saw the film—as its hero and the locus of the film’s ultimate meaning. I returned to watch the film again to see whether I found that plausible.

It was a different experience the second time around. I was now familiar with the basics of the film, so its primary effects were less visceral. This time I focused, instead, on some of its secondary aspects. I more closely followed the Polish girl’s story, which revolves around apples. Early in the film, we see a number of apples nestled under piles of straw. Later, we see a mysterious girl secretly placing apples in the straw; she is shot in infrared so that the heat of her body makes her glow white while the cold world around her is various shades of gray and black. Later still, as we watch the commandant’s children play in the foreground, we hear Höss discover that a fight has broken out among the prisoners over an apple. Höss orders that the prisoners be drowned.

In another scene, the glowing white girl plays a song as we hear Yiddish singing via voiceover. I was puzzled by the scene the first time around: the music felt intrusive, like it was coming from another film. But the second time around, more aware of Glazer’s intentions, it felt like a heavy-handed symbol. It turns out that the song was written by Joseph Wulf, a prisoner in Auschwitz who survived the war but never thought to do anything with his composition, which he deemed trivial. Wulf may have been correct in that assessment, but by having the girl rescue his words and his voice from the charnel house the film seems to be drawing a blunt contrast with the gleeful petty looting perpetrated by Madame Höss.

There is a contrast between the two women, for certain, but a facile and shallow one. It’s not much of a moral to say that the Polish resistance fighter who feeds hungry prisoners marked for death exists at the opposite end of a moral spectrum from the wife of the commandant of Auschwitz. Surely everyone in the theater knew that already. More to the point, though, the film gives no sense of the character of the girl beyond her virtuous acts. She is as much a symbol as the song is; if one wanted to learn what it was like to be her—as opposed to what it was like to be a member of the Höss family—Glazer’s film would be of no use at all. So Glazer is wrong about this aspect of his film, I think. Perhaps the girl on whom this character is based was a hero, but she is not the hero, not the protagonist of the film, not the point of identification, not the bearer of its message. Of course, we would like to identify with a hero, and audiences will do so whenever art invites us to. But The Zone of Interest forces us to do the opposite, to identify with the perpetrators. Which leaves the question of what to think about a film that, to appropriate a phrase, hijacks the Holocaust to achieve that effect.

The case against the approach taken by The Zone of Interest—or the case against Glazer’s speech applying it to Israel, and therefore against Israelis and their supporters watching the film and feeling its effects—is that Israel and the Jews have enough enemies eager to accuse them of being the new Nazis. Their motives may range from the expiation of their own burden of guilt with respect to the old Nazis to the weaponizing of rhetoric in an ongoing conflict between two peoples, both of which have blood on their hands. One could go further, in fact, and argue that the determination by some sign-waving critics to identify Israel as the “new” Nazi Germany derives in part from a recapitulation of the Christian idea of supersession (an idea repudiated by Pope John Paul II, among others). In rejecting Jesus, the supersessionsist argument goes, the Jews proved that they never understood their original revelation and thereby became the most un-chosen people. Similarly, in insisting that the Holocaust has a distinctive meaning for Jews about their own vulnerability and the exceptional nature of antisemitism, Jews are rejecting its “true” universal meaning about human nature and our capacity for evil. Worse, asserting any kind of distinctiveness for themselves, even as victims, they become like those who, waving the banner of Aryan distinctiveness, perpetrated the worst horror in Jewish history. Isn’t Glazer, by insisting that his film about Höss has lessons for Israel, saying something similar? And why would a self-respecting Jew join hands with him in that?

But if the Holocaust is a kind of inverted revelation, attesting to evil’s immanence, then presumably it is as open to multiple meanings as any other revelation. Indeed, it must mean many things—not only to those whose relationship to horrors like this one is simple but to those whose relationship with them is complex: those who could be, like nearly all of us, both victim and perpetrator, and want to avoid both fates. There’s no contradiction in saying that the Holocaust has a distinctive meaning for Jews, Western civilization, and humanity in general. For Jews, the Holocaust is a reminder of their vulnerability to destruction and what they must do to protect themselves from a recurrence. For Western civilization, it is a sign of the peculiar fault lines in its culture that lend enduring power to antisemitism. And for all of humanity, the Holocaust is an example of the dangers of dehumanization. The State of Israel falls into all three categories, so all three meanings are relevant to it.

I thought of Gaza while watching the film because I am Jewish, and because the effect of the film is to turn the gaze inward, to make us interrogate ourselves about how we might be monsters—not because we don’t know what we are doing but because we have decided not to see it as monstrous. Some one with different points of identification should, properly, have different associations, because, unless they are volunteers for World Central Kitchen, they should also be identifying with the perpetrators, not the Polish girl. If Glazer’s purpose in making the film is moral, though, I wonder whether that was a pedagogically wise strategy for him to force that point of identification. Even if we blind ourselves to our participation in horrors, most of us are not Höss, nor his wife, and never will be. The monstrous actions we refuse to acknowledge are nowhere near as egregious as those of Höss. Why isn’t it sufficient —better, even—to engage in analysis rather than introspection?

I think Glazer’s own answer comes in the film’s last moments, which I also reevaluated when I saw the film a second time. After the call where he muses to his wife about gassing the party guests, Höss trudges out of his office and down the stairs of the now-empty building. Then he stops and begins to retch, dry-heaving onto the stairwell, and turns to look down the hall. Abruptly, the scene shifts to the Auschwitz museum in the present day, where the tools of mass murder and the relics of the murdered are preserved for tourists and pilgrims to view. It is morning, and the employees of the museum are getting every thing clean and ready to welcome guests. We watch them going about their tasks and get a sense of how clean and orderly and well maintained it is—and then we cut back to Höss, staring toward the camera.

The first time around, I thought this was just a reverse shot showing Höss’s reaction to a vision of the future memorial. I thought, then, that he was realizing that Germany was going to lose the war, even its war against the Jews, no matter how many he murdered; that the Reich would fall and his victims would be remembered, and that this—not moral remorse but the anticipation that his life’s work would be a failure—was what turned his stomach. The second time around, I interpreted it differently. The scenes of the museum are framed in the same stark, objective way as the rest of the film, with static wide-angle shots, through which the workers move without comment. The implicit suggestion is that Höss and the workers at the Auschwitz museum have something in common: both are just doing a job, without feeling anything in particular about that job’s substance.

The implication, I think, is a startling one for an age committed to the idea that memorializing victims and educating the public about history’s worst episodes is crucial to avoid repeating those evils. On the contrary, the museum sequence, and the clinical, distancing way in which it is filmed, suggests that putting the Holocaust in a museum can itself be a kind of hijacking, a way of blocking identification rather than encouraging it, reaffirming the essential difference of the Nazis rather than their normalcy. Memorializing, on this reading, can have the effect of blocking perception, much as the ideological social and physical structures of Nazism blocked the proper perception of the worst evils in history. Obviously there’s nothing at all monstrous about a Holocaust memorial in itself. But remembering the past in this way, the ending suggests, makes it feel less present, so it will not help us recognize monstrousness in the present.

If I’m right about that, then part of the film’s purpose is to present itself as an alternative, or complementary, strategy to memorialization. Yes, we should learn about the evils of the past. But then—whoever we are and whomever we may identify with when we learn about those evils—we should have the emotional experience, which cinema is distinctly capable of providing, of feeling with the perpetrators, and feeling that identification as moral horror. The film’s fundamental project is to be a better prophylactic than learning about or even seeing a depiction of the past’s evils. That’s why, in that last shot, we aren’t looking at Höss looking at a vision of the future where he sees that his cause has failed. We’re looking at Höss looking at us.