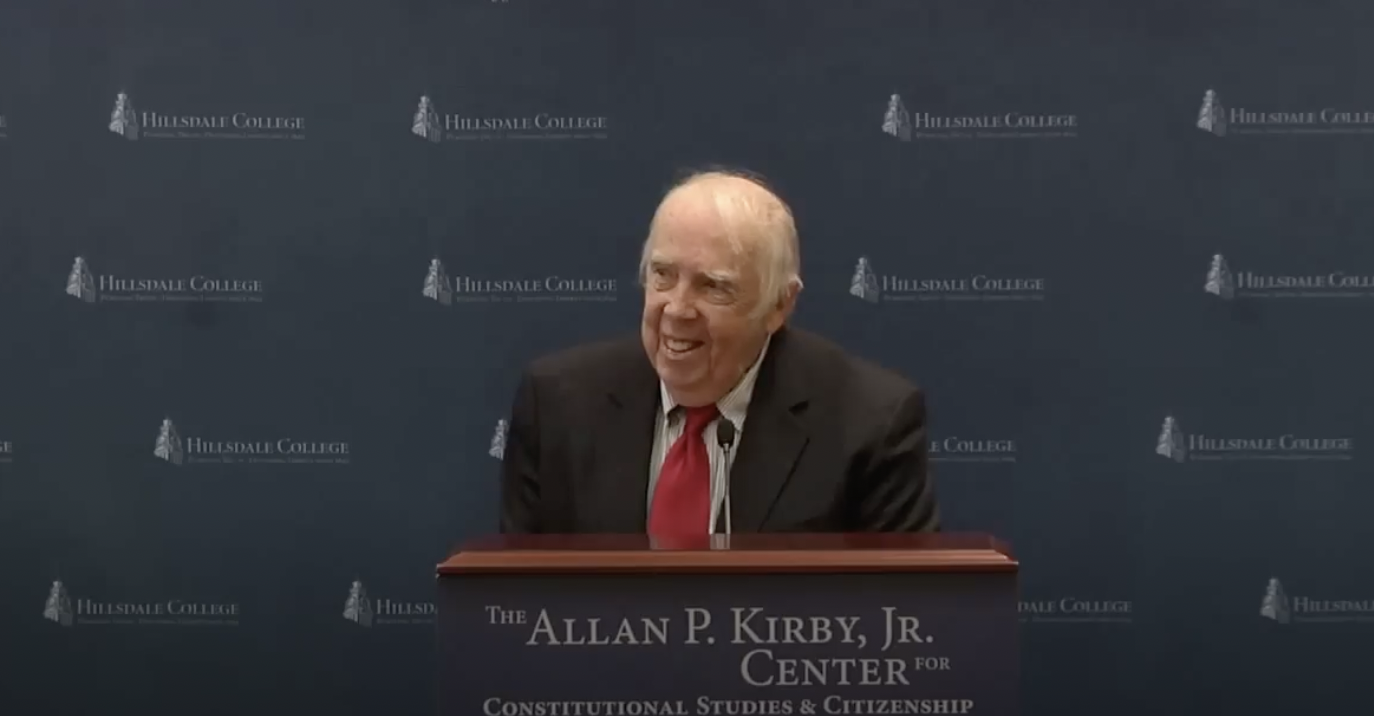

M. Stanton Evans had only to stand before a microphone to bring smiles to an expectant conservative audience. Would he report the latest grab for power from the Land of Leviathan—Washington, D.C.? Would he make an ironic remark, delivered in his sonorous voice underlaid with accents of Texas, the Midwest, and Yale, about the current liberal hero? Or would he offer an Oscar Wildean reflection on the undependability of conservatives when they come to power? “The trouble with conservatives,” he observed, “is that too many of them come to Washington thinking they are going to drain the swamp, only to discover that Washington is a hot tub.”

Second only to Bill Buckley, Stan Evans was the voice of conservatism in the pre–Ronald Reagan years. Yet he is unknown today to most conservatives under forty. “He was,” says his close friend and Reader’s Digest editor Ralph Kinney Bennett, “one of the greatest men you never heard of.”

He was a man of many parts, author of a revisionist biography of Senator Joseph McCarthy, who, he declared, had underestimated the number of communists in the U.S. government. He was the founder of the National Journalism Center that graduated more than 1,500 aspiring journalists, including notables such as Ann Coulter, John Fund, and Greg Gutfeld. Rare in her praise of anyone on the left or the right, Coulter described Evans as “great, amazing, incomparable.” Associated with William F. Buckley Jr. for decades, Neal Freeman said after Buckley’s passing that Stan had “become the indispensable man of our common enterprise, the wisest among us.”

Stan was the author of the iconic Sharon Statement, adopted by Young Americans for Freedom at its founding in September 1960 and widely regarded as a key document of modern American conservatism. The statement represented the three major strains of conservatism:

- Traditional conservatism: “Foremost among the transcendent values is the individual’s use of his God-given free will, whence derives his right to be free from the restrictions of arbitrary force.”

- Libertarianism: “The market economy, allocating resources by the free play of supply and demand, is the single economic system compatible with the requirements of personal freedom and constitutional government, and . . . is at the same time the most productive supplier of human needs.”

- Anticommunism: “The forces of international communism are, at present, the greatest single threat to these liberties,” and “the United States should stress victory over, rather than coexistence with, this menace.”

In the mid-Seventies, Stan laid down his most famous axiom, sometimes referred to as Evans’s Law of Political Perfidy: “When ‘our people’ get to the point where they can do us some good, they stop being ‘our people.’” He delighted in exposing the hypocrisies of the left, remarking of the National Council of Churches: “The National Council of Churches is alarmed at the Pat Robertson phenomenon, for mixing religion and politics. That’s a mistake [the Council] doesn’t make, since it has nothing to do with religion.” (Robertson was a well-known TV evangelist of the eighties.)

Stan edited or wrote for every important conservative journal in America. He was a contributing editor to Human Events for more than forty years and an associate editor of National Review for more than a decade. At twenty-six he was named editor of the Indianapolis News, making him the youngest editor of a daily metropolitan newspaper in America. Following Vice President Spiro Agnew’s public criticism in the late Sixties of the biased news media, Stan was invited to become a conservative commentator on CBS Radio as well as National Public Radio (NPR) and the Voice of America.

He was the epitome of an unsung conservative hero.

Medford Stanton Evans was born in Kingsville, Texas, on July 20, 1934, to strongly conservative, highly educated parents. He grew up in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where his father Medford Bryan Evans held a high position in the Manhattan Project and later with the Atomic Energy Commission. Stan’s mother, Josephine Stanton Evans, was a classics scholar. Stan graduated magna cum laude in 1955 from Yale, where he met and became friends with William F. Buckley Jr. Like Buckley, Stan was an editor of the Yale Daily News.

At Yale he read One Is a Crowd by the libertarian Frank Chodorov, whose book, he said, “opened up more intellectual perspectives for me than did the whole Yale curriculum.” He admitted that Chodorov “probably had more to do with the conscious shaping of my political philosophy than any other person.” Upon graduation he moved to New York City, where he became assistant editor of The Freeman, which Chodorov edited. Stan found time to do graduate work in economics at New York University under the famed free-market economist Ludwig von Mises.

The following year he joined the staff of Bill Buckley’s newly launched National Review and at the same time became managing editor of Human Events, remaining a contributing editor there until his death. A major Human Events responsibility was to mentor young conservatives like Bill Schulz, Allan Ryskind, and David Franke, who went on to major careers in journalism. Under the influence of National Review editor Frank Meyer, Stan expanded his philosophical thinking, blending traditionalist and libertarian thought in a political philosophy known as “fusionism.” “The idea that there is some sort of huge conflict between religious values and liberty,” he said, “is a misstatement of the whole problem. The two are inseparable.”

Although protesting he was no political philosopher, Stan more than holds his own in Meyer’s classic collection of essays, “What Is Conservatism?,” first published in 1964. He provides a tight analysis of the two main species of conservatives—“authoritarians” who urge conservatives to abandon an insistence on individual freedom, and “libertarians” who insist that conservatives give up “a Christianized view of man.” Stan argues that reconciliation of these apparently conflicting positions can be found in the U.S. Constitution.

It is noteworthy, he writes, that neither the “authoritarian” ideas of Alexander Hamilton nor the “libertarian” notions of Thomas Jefferson dominated the Constitution. Instead the conceptual balance struck by James Madison prevailed and was accepted by the Founders. They combined “a conservative mistrust of human nature with a libertarian desire to extend and nurture human freedom.” Their answer to both problems, writes Stan, “was the classic Anglo-Saxon reliance upon limited government.”

Stan handled the demands of being the editor of the Indianapolis News, a syndicated newspaper columnist, and a radio commentator with seemingly little effort. For the most part, he reserved his martini-dry humor for his public talks, beginning with a remark about an issue of the day. During the 1982 Falkland Islands crisis, precipitated by Argentina’s attempt to take back real estate over which Great Britain had enjoyed sovereignty for many years, Stan could not resist commenting. The crisis, he conceded, was a difficult one for conservatives. “On the one hand, we like imperialism. On the other hand, we like military dictatorships.” Liberals were nonplussed: Was he serious or not? Or was he mocking the liberal cliché that conservatives have no sense of humor? During the Watergate scandal, he used humor to lessen conservative disappointment with the president, remarking, “I was never for Nixon until Watergate.”

From 1971 to 1977, he served as chairman of the American Conservative Union (ACU), which in 1974 spawned CPAC, now the largest and most influential political conference in America, with more than ten thousand attendees. In 1976, ACU ran a $250,000 independent expenditure campaign in support of Ronald Reagan’s bid for the Republican presidential nomination. Reagan won the pivotal North Carolina primary with ACU’s help, establishing himself as the conservative alternative to the Ford–Rockefeller wing of the GOP and laying the foundation for his 1980 presidential victory. Stan called the North Carolina primary one of “the most important elections in terms of the conservative movement.” Under Stan, the ACU joined the landmark case Buckley v. Valeo. Along with liberal plaintiffs like the American Civil Liberties Union, it argued that limits on campaign contributions and spending violated the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech. In a per curiam decision, the Supreme Court agreed.

Always a good soldier for the conservative movement, Stan served as president of the Philadelphia Society, a trustee of ISI, an advisory board member of Young Americans for Freedom, and a member of the Council on National Policy. He enlivened their meetings with his contrarian humor. Tobacco, he declared, was his “favorite leafy vegetable.” His other favorite vegetable was ketchup, preferably on top of French fries. He doted on the Atlanta, Georgia, “elixir” Coca-Cola. He would come to a breakfast meeting, sit down amid the eggs and bacon and Danishes and coffee, and place a pack of cigarettes and a can of Coke in front of him. “My mother always told me,” he would explain, “that breakfast is the most important meal of the day.”

Ever cognizant of the rising generation, Stan taught journalism at Troy State University’s school of journalism, making the arduous weekly trip to and from the Alabama school for three decades. “The most important element in a story is you,” he told the students, “because you have to get the story accurately, completely, and fully in order to do your job as a journalist correctly.” Following his death, the university created the annual M. Stanton Evans Journalism Symposium on Money, Politics and the Media.

Stan Evans made a significant contribution to American conservatism in the field of letters. He wrote two of the most discerning books in the conservative canon: Revolt on the Campus and Blacklisted by History: The Untold Story of Senator Joe McCarthy and His Fight Against America’s Enemies. Published in 1961, Revolt described a conservative revolt on the American campus against liberal conformity and collectivism and made a fearless prediction.

While admitting that the majority of students were liberals, Evans wrote that some 5 percent of them were “articulate, forceful and resourceful” conservatives. In twenty years, he predicted, they would be “the nation’s journalists, teachers, clergy and leading businessmen.” In fact, he said, the conservative movement in fifteen or twenty-five years “is going to be taking possession of the seats of power in the United States.”

That seemed far-fetched at a time when liberal John F. Kennedy had just been elected president, Walter Cronkite was “the most trusted man in America,” Robert A. Taft and Joseph McCarthy were recently dead, and only Senator Barry Goldwater was articulating conservative ideas in Washington. Twenty years later, almost to the day, a proudly conservative Reagan was elected the fortieth president of the United States.

In Blacklisted by History, published in 2007, Stan examined the career of one of the most controversial politicians of the twentieth century, Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, beloved by millions of conservatives. Many historians have written that from 1950 to 1954, an anticommunist “reign of terror” raged in America, during which the loyalty of patriotic Americans was impugned, innocent people lost their jobs, and public dissent was nearly eliminated. One man and one man alone, they assert, was responsible—Joseph McCarthy.

Not so, insisted Stan Evans, and in a 663-page masterpiece of research and analysis based on confidential FBI files he obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, he shows that McCarthy was right—there were dozens of communists in the State Department and other government agencies. Furthermore, most of McCarthy’s investigative methods were careful, thorough, and of the highest ethical standard. His adversaries were the ones who practiced McCarthyism and conducted a Star Chamber investigation of the Wisconsin senator. A volunteer worker in his Washington office summed up her experience: “He eats, sleeps, and lives his crusade. His whole conversation is what to do next to further ‘cleaning out the subversives.’”

Typical of Stan’s deadly humor, points out Ralph Bennett, was the chapter in Blacklisted by History about the pro-communist “scholar” Owen Lattimore. Stan quotes from a Lattimore article in which the Soviet apologist portrays the slave-labor camp at the Magadan-Kolyma gold mines as a kind of Siberian arts colony with a “first-class” orchestra and ballet company. “Instead of the sin, gin and brawling of an old-fashioned gold rush,” writes Lattimore, there were “extensive greenhouses growing tomatoes, cucumbers and melons to make sure the hardy miners get enough vitamins.” Stan follows this grotesque description of a Gulag camp by recalling the historian Robert Conquest’s description of Magadan-Kolyma as one of the deadliest labor camps, killing about one-third of its inmates each year. “Of course,” comments Stan, “without all the cucumbers and tomatoes, the death toll might have been even higher.”

Once queried by Time as to his politics, Stan replied: “I think my philosophy is pretty close to the farmer in Seymour, Indiana. He believes in God. He believes in the U.S. He believes in himself. This intuitive position is much closer to wisdom than the tormented theorems of some of our Oxford dons.”

Stanton Evans died on March 15, 2015, at the age of eighty, having received awards and honorary degrees from nearly every conservative institution in America.

Somewhere in Heaven, Stan is telling a story about St. Peter, and all the angels assembled are laughing hard.