The contrast between the success of America’s Cold War strategy and the failure of the strategy Washington has pursued for the last thirty-odd years could not be more striking. In 1992, the U.S. had no rival anywhere in the world. Today, China contends to be the strongest power in the Pacific. Twenty years of conflict with Iraq—beginning with the 1991 Persian Gulf War and ending with the official withdrawal of U.S. forces from the country in 2011—failed to bring stability, let alone liberal democracy, to the Middle East. And twenty years of U.S. combat operations in Afghanistan concluded in 2021 with that country immediately reverting to the rule of the radical Islamists we overthrew in 2001.

The Cold War victory itself has turned to ashes. The U.S. expanded NATO yet failed to contain post-Soviet Russia. For nearly a decade, a newly free Russia posed little threat to its neighbors, but whatever opportunity existed to incorporate this former opponent into the U.S.-led order was squandered. American policymakers took pride in having contributed to the fall of the Soviet Union through far-sighted strategy, but they had no success in devising equally far-sighted strategies to win the peace and secure Russian democracy.

The architects of America’s unsuccessful foreign policy of the last three decades have been almost uniformly liberals. That has been true in Republican administrations as well as Democratic ones. Liberal internationalists tend to believe that harmony is the default condition of mankind. On that assumption, the fall of authoritarian or totalitarian regimes should always produce democratic and liberal outcomes, though they may take time to emerge. That’s one reason Washington invests billions in nongovernmental organizations, international institutions, and “peacekeeping” missions around the world. After a despotism is toppled, social work is all that’s needed to set a country right, even if some of that social work must be performed by soldiers.

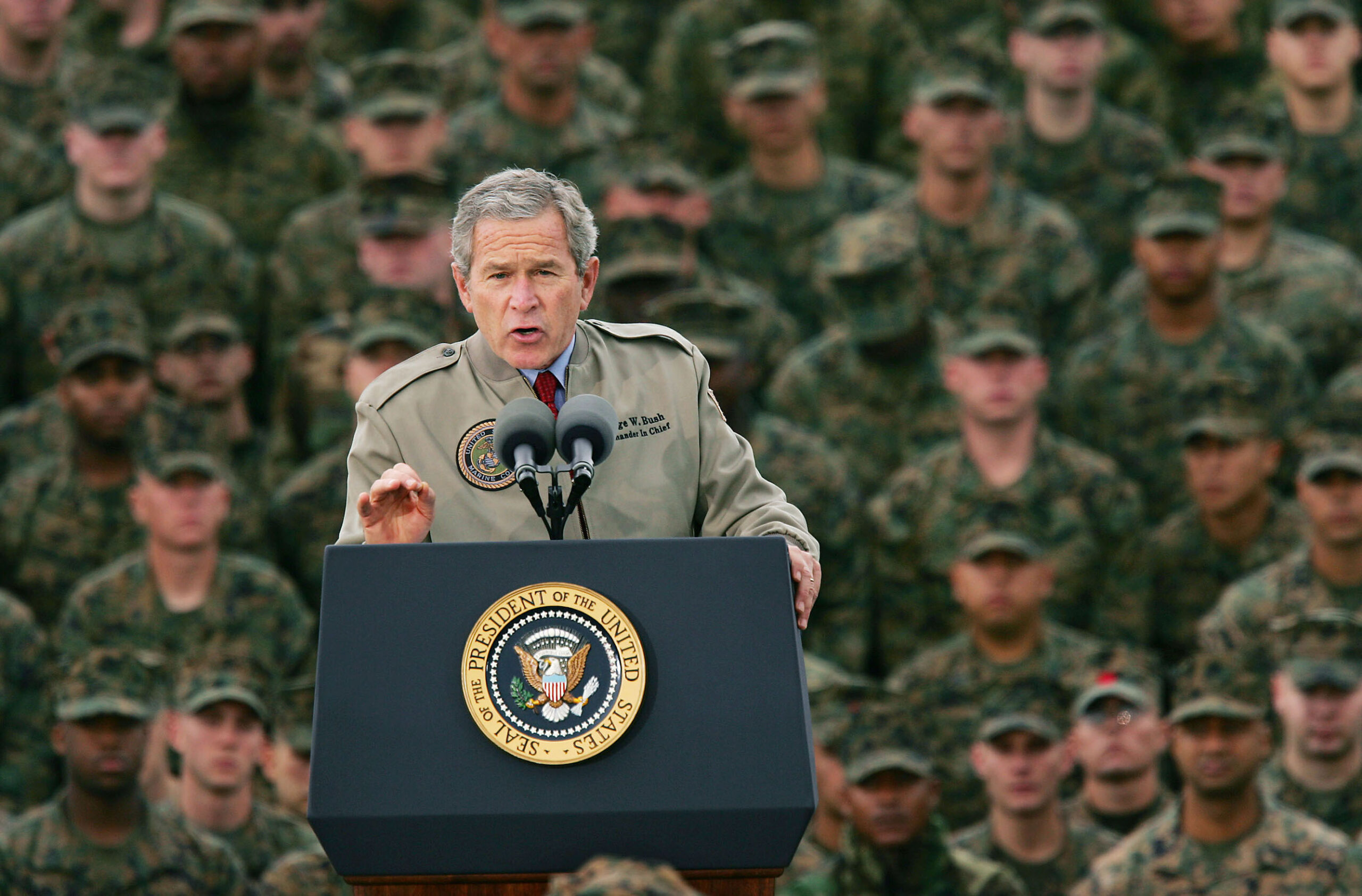

A certain kind of self-described conservative or realist believes much the same thing, only with a narrow emphasis on the formula’s first part, the destruction of evildoers. These quasi-realists insist that they are not democratic idealists or liberals (or indeed neoconservatives). Yet they have only half a foreign policy and must rely on liberals to supply the other half. George W. Bush could decry “nation-building” when he ran for president in 2000, but once he went to war he and his administration could conceive of no alternative to prolonged occupation and nation-building in both Iraq and Afghanistan. John Bolton is not so much a realist as an embarrassed neoconservative, one bashful about admitting that nation-building is the natural corollary of regime change as practiced by an overwhelmingly liberal foreign-policy establishment in both parties. Right-leaning defense intellectuals might focus on enemies to be defeated, but they defer to their liberal colleagues when it comes to envisioning peace.

A bipartisan liberal foreign policy is failing once again under President Biden. It presents no answers to the Israel–Gaza crisis. Gaza is as inhospitable to liberalism as Afghanistan ever was, if not more so, while Israel cannot wholly adopt liberalism without endangering its own existence. The Biden administration, unable to make sense of this reality, proceeds to arm Israel while condemning the country for not fighting the war by liberal means or for liberal ends. Republicans in Congress characteristically see the immediate need to eradicate Hamas but imagine the peace will take care of itself. American policy is similarly aimless in Ukraine: neither the Biden administration nor congressional Republicans outline a plausible path to victory no matter how much aid the Ukrainians receive. The bipartisan strategy is all but explicitly one of deferring defeat.

Politicians who for twenty years offered Americans vague yet confident assurances that victory in Afghanistan was around the corner now say the same about Ukraine. Kyiv may not be Kabul, but the least qualified people imaginable to make that determination are the center-left and center-right politicians and intellectuals who were so unshakably wrong the last time. Whether or not the war is different, the chorus is unchanged.

What has not worked for the last thirty years is not about to start working tomorrow. A serious alternative to the course down which liberal in both parties have led America is overdue for consideration. Indeed, every facet of the “liberal international order” built during the Cold War should have been subjected to rethinking in 1991. But those public figures and scholars who did propose a new path were for the most part demonized. Today conservative critics of the disorder to which post–Cold War liberalism has given rise continue to be dismissed in Washington, D.C. A recent event at the Center for the National Interest is a case in point.

The center is the publisher of the National Interest, a foreign-policy magazine founded in 1985 by Irving Kristol and Owen Harries. Kristol was one of the few neoconservatives then or now who accepted the label without objection; he titled one book Reflections of a Neoconservative. Harries was an Australian academic who had helped shape his country’s foreign policy after the Vietnam War. He came to Washington in the early 1980s to work at the Heritage Foundation.

Harries and Kristol were both staunch anticommunists, and although the National Interest was not an exclusively right-of-center periodical, it had Reaganite affinities that distinguished it from older foreign-policy journals. In 1989 it also distinguished itself as the magazine in which a thirty-six-year-old State Department official named Francis Fukuyama published his essay “The End of History?” Fairly or not, Fukuyama’s essay and the book he later published under the same title—minus the question mark—became a totem for the emerging post–Cold War liberal intellectual consensus.

Yet Harries was not persuaded by Fukuyama’s case for the triumph of liberalism. His views were not entirely aligned with Kristol’s, either, and as the Soviet empire crumbled the National Interest became the venue for competing schools of foreign-policy thought, mostly on the center right, to lay out their agenda. Patrick Buchanan, Charles Krauthammer, and Jeane Kirkpatrick were among the right-of-center intellectuals who contributed to a series of essays in the magazine about the future of U.S. engagement with the world. Kirkpatrick and Buchanan both advised America to look homeward and reconsider Cold War–era alliances and institutions.

The National Interest, like other small magazines, has had its share of travails over the decades. Under different editors and publishers, it has moved somewhat left or right of center while remaining broadly realist and well-connected with D.C. policymakers and intellectuals. Its current editor, Jacob Heilbrunn, is a political moderate who enjoys casting a critical eye on the left and right alike—but on the right especially. His first book, published in 2008, was a stinging account of the neoconservatives called They Knew They Were Right: The Rise of the Neocons. This year he published an even more astringent volume on what he believes to be the genealogy of Donald Trump’s outlook on foreign affairs. It’s called America Last: The Right’s Century-Long Romance with Foreign Dictators.

In May, the Center for the National Interest hosted a luncheon panel to discuss the book, featuring Heilbrunn and the new executive director of the American Conservative, Curt Mills, who once worked for Heilbrunn as a National Interest reporter. Heilbrunn gave a précis of his book, which argues that from World War I onwards the American right has had a fondness for authoritarian leaders abroad, a fondness expressed by obscure figures and famous names such as H. L. Mencken and Donald Trump toward foreign strong men ranging from Kaiser Wilhelm II and Benito Mussolini to Viktor Orbán and Vladimir Putin. Heilbrunn casts a wide net—with wide holes. Both his tyranny-loving right-wingers and his gaggle of dictators (or even unfashionably illiberal democrats) are wildly heterogenous. As he personally presented his material, however, Heilbrunn made a point to say that “conservatives” were not his target: “the right” was.

The trouble with such a disclaimer is that Heilbrunn’s method of attacking the right is identical with the way in which foreign-policy liberals have historically attacked conservatives. The pattern is the same all the way back to Edmund Burke, who was charged by the British admirers of the French Revolution with being a lover of Bourbon absolutism. The ideological factions that would soon come to be called “liberal” or “left-wing” tarred “conservative” or “right-wing” opponents of revolutionary radicalism as enemies of freedom itself. Great conservative statesmen like Klemens von Metternich, who restored order to Europe after the Revolution and Napoleon’s wars, were portrayed even by liberals and leftists who did not suffer repression within the bounds of the Austrian empire as authoritarian monsters who took tsars and tsarism as their models of rule. Peter Viereck wrote one of the first books of the post–World War II conservative revival in America—1949’s Conservatism Revisited—in part to clear the names of Burke and Metternich.

This was not only a European phenomenon. Loyalists in the American Revolution often had impeccable Whiggish pedigrees, yet they were branded “Tories” by the patriots, at a time when the word “Tory,” on both sides of the Atlantic, carried the implication of allegiance to the Stuart dynasty and its purported desire to re-establish the unchecked divine right of kings. In the generation after the revolution, Jefferson Democrats lobbed similar accusations against their Federalist opponents, only this time it was the House of Hanover and George III that the left-liberals said their foes wanted to restore.

I suggested to Heilbrunn that, despite his caveats, he was really accusing conservatives of being conservative. Some of the least well-known figures whom Heilbrunn discusses were indeed promoters of tyrants and tyranny. George Sylvester Viereck—Peter Viereck’s deeply troubled father (who may also have been a grandson of Kaiser Wilhelm I)—was an agent of Germany in both world wars. Mencken was not, though the deeply illiberal wartime government of Woodrow Wilson investigated and harassed him. One semi-literate informant reported to the American Protective League, an organization sponsored by the State Department, that Mencken was a close acquaintance of “Nitsky, the German monster,” meaning Nietzsche, about whom Mencken had written a book but whom he never met. Albert Jay Nock—an actual friend of Mencken’s who would become an important early influence on such post–World War II conservatives as William F. Buckley Jr., Robert Nisbet, and Russell Kirk—also fell afoul of the Wilson administration, which imposed postal censorship on an issue of the Nation in which Nock criticized the labor leader Samuel Gompers, a valued partner in Wilson’s war effort.

Mencken did indeed profess admiration for Wilhelmine Germany and had many satirical and philosophical critiques of democracy. But his practical politics were anti-statist and most congruent with libertarian statesmen like Missouri’s Senator James A. Reed, a fellow Democrat who opposed President Wilson’s power grabs. Nock was a philosophical anarchist who saw World War I as a war to save British imperialism, and while Heilbrunn finds Nock’s 1922 book written in exculpation of Germany, The Myth of a Guilty Nation, unpersuasive, it’s an antiwar work, not a pro-tyranny one—though many a warhawk then and now has pretended not to know the difference.

The particulars of Heilbrunn’s indictments are less important than the spirit of the work, however. Heilbrunn, whom I’ve known for many years, is no doubt sincere about the distinction he sees between the right and responsible conservatives. But it’s a subjective distinction that historically counts for little: whenever liberals criticize conservatives in matters touching on foreign policy, the charge of siding with dictators recurs. This is because liberals, when they are not actually the party of revolution, nonetheless sympathize with the revolutionary impulse: the intuition that only wicked old institutions prevent human beings from living in freedom and harmony. Conservatives are on the side of those very institutions—they even believe in defending them by force. Revolutionary sentiment doesn’t strike at the heart of liberal beliefs in human harmony and progress, but counterrevolutionary sentiment does. What’s more, morality for liberals and revolutionaries alike depends on destroying something, whatever external evil prevents humanity from realizing its natural goodness. Conservative morality involves the use of force to resist destruction, even with the full awareness that the institutions being saved are imperfect.

Liberals are capable of learning from conservatives, and vice versa. But the near monopoly that liberals—including Republican and “conservative” liberals—have enjoyed in precincts where foreign policy is discussed and made has encouraged liberals to believe their own myths about their rivals. After thirty years, it’s hard for liberals to remember what conservatism and non-liberal realism contributed to the strategies that made America successful in the Cold War. Those strategies accepted the world and humanity as inherently imperfect, took account of the persistence of religion and nationality, and recognized that many less than fully liberal and democratic regimes and movements would be needed as allies against Soviet influence. Countering radicalism, not promoting a counter-radicalism, was typically the aim.

The conservative sees in revolution the potential for the dissolution of all order, with the attendant chaos causing even greater suffering than the typical dictator might inflict. And the most likely exit from chaos involves a return to the harshest form of order. A revolution against one wicked regime clears the way for another, with all the more bloodshed in the interval between despots.

In The Roots of American Order, Russell Kirk, a conservative whom Heilbrunn includes in his indictment of the right, relates the tale of a friend who was born in Russia and lived during the Bolshevik Revolution:

When the Bolsheviks seized power in St. Petersburg, he fled to Odessa, on the Black Sea, where he found a great city in anarchy. Bands of young men commandeered street-cars and clattered wildly through the heart of Odessa, firing with rifles at any pedestrian, as though they were hunting pigeons. At any moment, one’s apartment might be invaded by a casual criminal or fanatic, murdering for the sake of a loaf of bread. In this anarchy, justice and freedom were only words. “Then I learned that before we can know justice and freedom, we must have order,” my friend said. “Much though I hated the Communists, I saw then that even the grim order of Communism is better than no order at all. Many might survive under Communism; no one could survive in

general disorder.”

To liberal eyes, that paragraph reads as an endorsement of communist dictatorship. The conservative sees it as an acknowledgement of reality. Our foreign policy since the end of the Cold War has consisted of campaigns against dictators of various kinds—and has paid scant attention to the creation of an alternative order first. Our own revolutionary forefathers had an alternative order—the one embodied by their own local institutions—before they overthrew British rule. And after they had won their independence, the greatest Americans of the age lent their genius and prestige to the counterrevolutionary work of strengthening order with a new Constitution, not in place of local government but in addition to it. The Cold War was won much as the American Revolution was—by institutions of order that were already in place, prepared for the day communism lost its grip. Deposing a dictator or despotic system was the final step, not the first.