From the mid-seventeenth century until Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, France was what we would today call a superpower. Not only did international relations tend to revolve around France’s pursuit of its European and global ambitions; the French language, philosophy, theology, art, and fashion dominated the outlook of elites throughout the European world.

The beginnings of that dominance can be traced back to the House of Valois’s victory over Plantagenet England during the Hundred Years’ War and the French monarchy’s successful consolidation of its control over the hexagon of modern France. But the more immediate antecedents of France’s rise to supremacy lay in the statesmanship of Cardinal Armand de Richelieu, chief minister of Louis XIII. Besides successfully preventing the disintegration of the French state as the country was torn apart by fierce religious conflict between Huguenots and Catholics, Richelieu has good claim to the distinction of having decisively checked the growth of the Habsburg empire and facilitated France’s eclipse of Spain as Europe’s leading continental power.

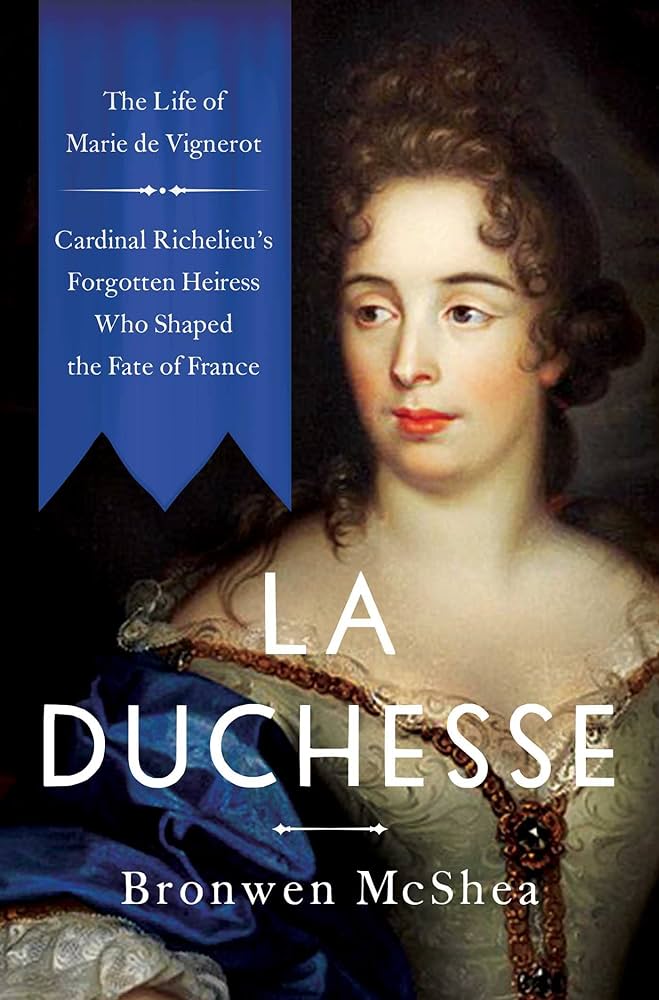

Richelieu’s world was a man’s world. This makes it all the more remarkable that Richelieu made his niece Marie-Madeleine de Vignerot (1604–75), the duchesse d’Aiguillon and a Peer of France, the prime heiress and administrator of his vast estates. The historian Bronwen McShea observes in La Duchesse: The Life of Marie de Vignerot that this represented a violation of longstanding French norms insofar as Richelieu sidelined his nearest male relatives in favor of someone who, for all her titles, was in the end a mere woman. Along with the financial assets associated with Richelieu’s estate came immense power. McShea demonstrates that this mere woman didn’t hesitate to use her influence to advance distinct political and religious objectives.

By her own account, McShea had two goals in writing this book. The first was to ensure that “Marie would recognize herself in this portrait.” The second was to put “a strong, high-achieving, faithful, but also flawed and real woman of the Catholic Church and of France’s Golden Age back onto history’s center stage.”

Had Marie de Vignerot been a man, she would likely be as well known today as Richelieu, his successor as chief minister Cardinal Jules Mazarin, and even le roi soleil himself, Louis XIV. Gradually, however, she disappeared from French history. That she was a woman may have had something to do with this, but McShea emphasizes other reasons: the fact, for example, she always lived in her uncle’s shadow. Even after his death in 1642, Marie was considered an extension of sorts of Richelieu’s famous career and subsequently was buried by it in the history books. Yet, McShea argues, any history of Richelieu is incomplete without addressing the role of someone whom the political and religious elites of Europe simply called “La Duchesse.”

To rescue Marie from her relative obscurity, McShea draws upon many published French-language studies of the period and numerous unpublished sources and manuscript collections. These range from documents such as correspondence between Richelieu and Marie to the memoirs of prominent courtiers. McShea has also thoroughly investigated archives across two continents, especially those of religious orders noted for keeping meticulous records (most notably the Jesuits), found in locations such as Montreal; Paris; Cambridge, Massachusetts; and Vatican City.

In many cases this gives us direct insights into thoughts of Marie and others in her life that were meant to remain private. We see the spiritual and intellectual seriousness of Marie’s religious faith, which was characteristic of seventeenth-century French Catholicism during the Counter-Reformation and which impressed even many Protestants of the time. But we also encounter Marie’s deep realism about the human condition, her awareness of her contemporaries’ strengths and limitations, and her subsequent willingness to act decisively and, occasionally, ruthlessly.

Deep religious conviction and political practicality are not often found in the same person. Marie, however, had both. Indeed, she was positively entrepreneurial in her promotion of her favored interests. Chief among these was the projection of French power across the globe by supporting the efforts of religious orders to evangelize the native peoples of the Americas, Africa, and East Asia. For Marie, political and religious concerns went together: the cause of France was also the cause of the Church.

Marie’s characteristic determination was evident from a young age. Like many women of her rank, she was quickly married off. At the age of sixteen she was wed to a fighting nobleman, Antoine de Grimoard de Beauvoir du Roure, Marquis de Combalet. He died just two years later at the siege of Montpellier during the first Huguenot rebellion.

Her cardinal-uncle expected Marie to quickly remarry an even higher-ranking nobleman, possibly of princely rank, to advance Richelieu’s political designs. That Marie declined to do so testifies to her independence of character. Few people were willing to cross someone who was already a powerful figure in French politics. Marie, however, decided that she wanted to become a Discalced Carmelite—then as now one of the most demanding of cloistered religious orders. In the end, Richelieu was able to pressure Marie not to enter religious life. She declined, however, to remarry. Instead, she became part of Richelieu’s household, just as he was on the point of becoming France’s de facto prime minister.

Marie was especially well positioned to promote her uncle’s agenda. For one thing, Marie’s position at the royal court gave her access to the informal networks of aristocratic women who, in their own way, exerted subtle influence upon their suitors, husbands, and lovers. Despite their inferior status by virtue of their sex, women who moved in the royal court of seventeenth-century France were able to accumulate and use power by virtue of friendships, connections, and, above all, their ability to exercise patronage.

Even more important was Marie’s closeness to the Queen Mother, Marie de’ Medici, perhaps one of the most formidable political figures in French history. Marie de’ Medici and Richelieu did not always see eye to eye (to put it mildly). In her role as the queen’s dame d’atour, Marie was able to see far beyond her formal responsibilities of supervising Her Majesty’s clothing arrangements or managing numerous staff. She could also keep an eye on the queen’s militant brand of Catholicism. This was useful to Richelieu, who did not necessarily regard the queen’s religious severity as being in France’s interests, not least because it was likely to alienate those French Catholics who believed that some type of rapprochement needed to be made with France’s Huguenot population if France was not to see its great power status destroyed by an all-out religious civil war.

Much of McShea’s account of Marie’s life is focused heavily upon her place in the endless intrigues surrounding, and sometimes initiated by, her uncle. Marie’s periodic efforts to follow through on her ambitions to enter religious life may indicate that she did not always find such constant maneuvering to her taste. McShea suggests, however, that Richelieu’s reason for his obstruction of this desire to enter the cloister was not that she was a mere pawn for him to play on the chessboard of French politics. Instead, the cardinal was able to look beyond the convention of his times and recognize that his niece was superior in character and intellect to other members of his extended family. The very fact that she would have preferred to lead a cloistered life meant for Richelieu that “she would prove a trustworthy assistant to his ambitions,” as McShea puts it.

Marie’s elevated position at court before and after Richelieu’s death, her closeness to the Queen Mother, and her acquisition of great wealth following her husband’s death and that of Richelieu also gave her the freedom to pursue many of her own ambitions. Some of those interests were intellectual and on a scale beyond that of most aristocratic women of her time. She helped support, for example, talented mathematicians, including one Blaise Pascal, and even appears to have supported the publication of René Descartes’s Discourse on Reason.

At the same time, Marie put her extensive contacts and financial weight behind figures such as the priest Vincent de Paul and the religious sister Louise de Marillac—both later canonized—who embodied the missionary zeal of seventeenth-century French Catholicism. Marie turned out to be a forceful patroness and was not afraid to tell these strong-minded individuals how she thought they should carry out their missions, whether in mainland France, New France in North America, or French colonial and missionary outposts in Africa and Southeast Asia. To the extent that she enabled them to spread the Christian Gospel and French power far beyond France’s shores, Marie’s influence assumed global dimensions.

La Duchesse lived a full life, and, as McShea illustrates, she exemplified how some iron-willed aristocratic women—Marie de’ Medici, Anne of Austria, and Henrietta Maria of England, to name just a few others—were able to shape events in ways that defy the stereotypes often projected back on the seventeenth century. In doing so, McShea has not only brought back to life someone who has long deserved such a thorough biography. She has also demonstrated that power wielded from behind the scenes is often the most consequential.