Climate is the dominating and definitive issue of our time, a compound of acutely emotional considerations concerning science, politics, society, culture, anthropology, and religion, the breadth and complexity of which has yet to be recognized comprehensively.

In the late ’70s and early ’80s, a fresh movement on behalf of “wilderness” was growing and coalescing, chiefly in the Rocky Mountain West. Its members believed in what they called “biocentrism,” radical activism including threats, physical confrontation, and the destruction of private property such as bulldozers, employed by companies involved in the “rape” of the land. At the center of this movement was the organization Earth First!, headed by an activist from Tucson named Dave Foreman. Other aggressive biocentrist groups founded about the same time include Sea Shepherds, Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, Rainforest Action Network, the Animal Liberation Front, and Hunt Saboteurs.

In 1968, Desert Solitaire, by the novelist and essayist Edward Abbey, appeared. It is a literary work on the order of Walden or Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek: an intensely personal account celebrating nature through adventure and description, and only secondarily a social and political “statement.” Desert Solitaire is not a book written for policy people but for outdoorsmen, and then not in the sense of sportsmen but of men and women for whom nature is not just their second home but in a very real sense their first one—far more so, indeed, than Walden was for Thoreau.

None of this prevented Abbey from developing into a cult figure of the biocentric environmentalists in general, and Earth First! and Dave Foreman in particular. Flattered by their adulation, Abbey tolerated and even enjoyed them, while refraining from endorsing their more extreme ideas and behavior. The explicit rule of his heroes and heroines in his monkey-wrenching novels about dam-blowing and other joyous acts of environmental sabotage was “Nobody gets hurt.” It was by no means clear to anyone, including itself, how far Earth First! was prepared to observe this rule.

For two decades Abbey had a literary and personal following whose devotion was unshakeable, admirers for whom he was nothing less than a prophet. There is no one like him today, the environmentalist movement having devolved over the thirty years since his death into a collection of leftist ideologues and propagandists who, if they think of him at all, remember Edward Abbey—a Jeffersonian democrat and old American republican—as an anti-feminist, anti-immigrant, and racist reactionary.

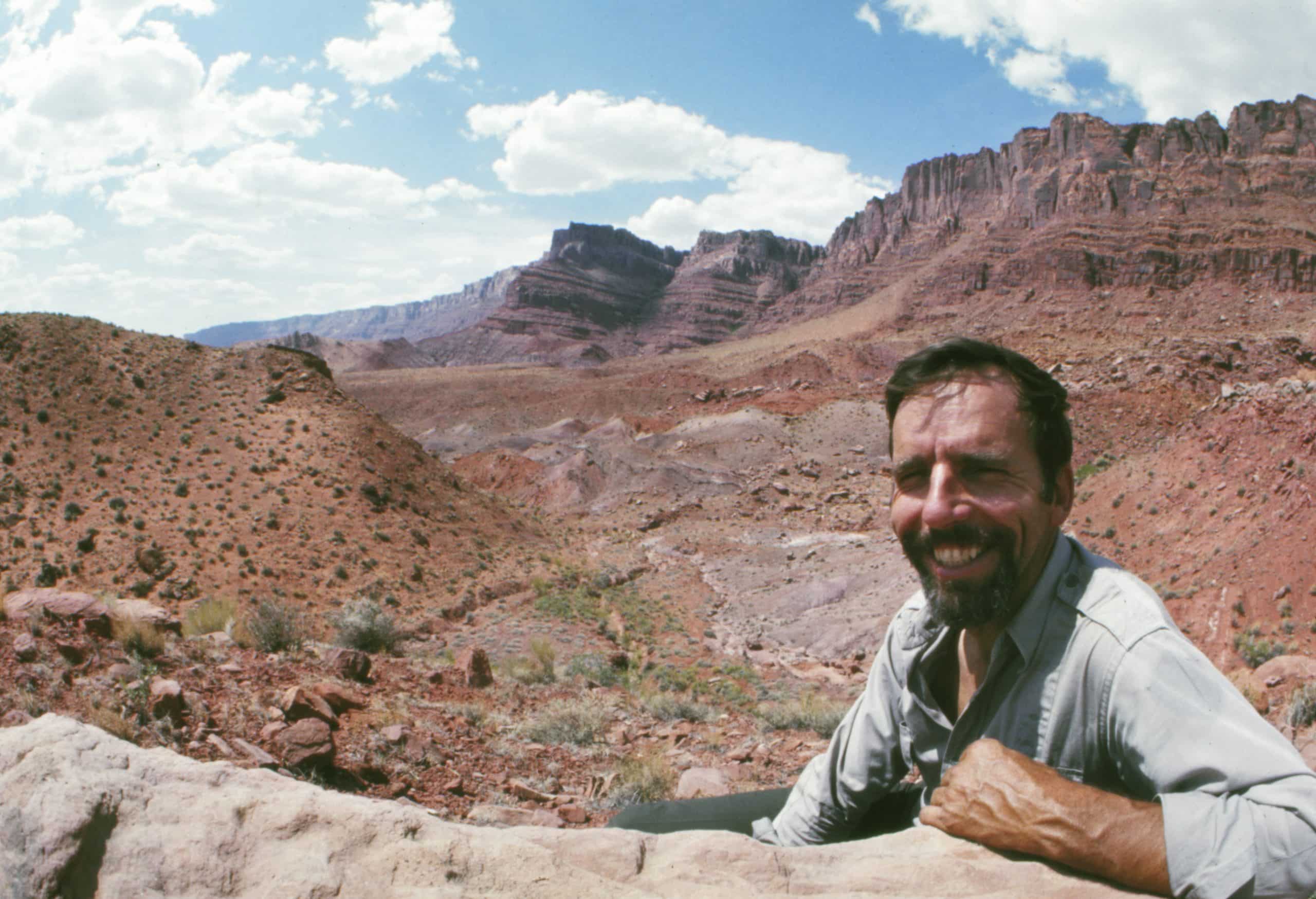

While I will not venture to assert what Abbey’s response to the climate change crusade would have been—he died in 1989—Abbey and I thought alike. More importantly, we felt alike, loved and hated together on certain matters regarding nature and the proper relationship between the human and the natural world, while diverging on others, including the most fundamental ones. This essay being an attempt at working through, sorting, and resolving some of these feelings and ideas, I begin with a few memories and reflections on an old friend long dead.

The postal card stamped TUCSON AZ arrived one brilliant fall morning at my home in Kemmerer, Wyoming, around the beginning of November 1988. Boxed somewhere with my wholly unsorted papers in the cellar, it exists in memory as a humorous card in bold colors showing a horse and a cowboy in a comedic situation, one of a number of such communications I’d received from Edward Abbey over the years.

Our correspondence typically ran on the following lines: “When are you going get down here to God’s country?—Ed”; “Too hot in summer where you are. Why don’t you come here for a visit and cool off instead?—C”; “Too damn cold up there.—Ed.”

This time was something different. “I’ll be signing books at Weller’s in SLC week after next. We could meet for lunch afterward”—or something close to that. “Weller’s” is Sam Weller’s Zion Bookstore on South Main Street, a few blocks south of Temple Square. Ed’s new book—Hayduke Lives!, the sequel to The Monkey Wrench Gang—had just dropped back on the East Coast. I chose what I considered to be a suitably amusing card and wrote back, saying I’d be on hand on the specified day. We agreed to meet at Lamb’s Café, a simple but excellent restaurant directly across South Main from the bookshop, where I often ate breakfast or lunch while in town. It made superior martinis for a place founded, owned, and run by Mormons—or by any other standard you can mention.

I’d seen Ed last in the summer of ’87, when he, his wife Clarke, and the two youngest of his five children were living in a house rented for the summer on Moenkopi Drive in Moab, Utah. (Ed had five children by five wives, a fact he excused when challenged by members of the population control crowd by explaining that the total averaged out to the environmentally responsible number of one child per wife.)

Back then I’d driven the 350 miles between Kemmerer and Moab in my old Land Cruiser and spent several days being royally entertained by the Abbeys: savoring Clarke’s excellent Southwestern cooking, floating the Colorado River above Moab with Ed in his boat, and riding horseback into the La Sal Mountains, while discussing, among many other subjects, a rough plan to make an extended exploration along the Arizona–Mexico border and write up the experience separately for eventual publication. Having returned the horses to the Pack Creek Ranch south of town, we sat afterward in the pickup truck while I drank a couple of cold beers and Ed a few tablespoons from a bottle of cough medicine, for a non-alcoholic kick. I knew he’d been experiencing trouble in his gut for years, and alcohol didn’t help. Before we’d started out that day he’d shown me where he was hiding the keys inside a wheel well. “In case something should happen to me,” he’d explained in a diffident way.

For our meeting in Salt Lake I parked downtown and walked half a block north to Weller’s, where Ed was signing a few last copies and helping to box up what hadn’t been sold. Then we crossed South Main and went into Lamb’s, where the lunch crowd was finishing up. We took a booth facing the bar and backbar, and when the waiter came over I ordered a dry martini. So did Ed.

“I thought you weren’t supposed to drink,” I told him.

“Oh, one little drink now and then can’t hurt.”

After thirty-five years I no longer recall what we discussed for the next two hours. We paid up and walked out together, down South Main to my truck. Ed crossed the street with me and waited while I unlocked the door. Then, as I prepared to step up to the cab, he came forward and embraced me in a full bear hug. He was a big man. I expect the sensation was similar to what the hunter on my family’s property in Vermont decades ago felt when the bear he’d just shot took him from behind and crushed the life out of him when he was still twenty feet from the rifle he’d set aside against a tree.

I never saw Ed again, though we stayed in touch. Then, on March 15, I had a call from a friend in Salt Lake who had just heard on the news that Ed Abbey had died the day before at his home in Tucson. He was sixty-two years old. The martini he’d drunk with me in Lamb’s probably hadn’t killed him, but it certainly hadn’t done him any good.

His body, as stipulated in his will, was packed in dry ice in his old sleeping bag by his widow, his brother-in-law, and two of his oldest friends in mayhem. They loaded Ed into the bed of his pickup and drove him west of the city, across the Tohono O’odham reservation to a location in the Sonoran Desert between Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and the Barry M. Goldwater Range Air Force Base. They dug a hole in the caliche on federal land, buried him there, and piled rocks on top of the grave to keep the coyotes from digging him up. All completely illegal, of course, but the authorities apparently decided to look the other way: Ed had been enough of a nuisance for them in life without their asking for trouble with his public post mortem.

A decade later Tom Sheeley—the late classical guitarist who had joined Ed, pulling an oar, on float trips down the Colorado River many years before—drove out with me to try to find the grave. We had instructions dictated over the phone by the brother-in-law, a medical doctor on the staff of the University of Utah, that sounded credibly precise, so we were pretty confident of success. We made camp for the night on the desert, built a big fire of mesquite branches and cholla, burned a steak, drank a lot of red wine, and the next morning commenced the hunt. Since the burial a decade before, the bank against which the grave had been dug had collapsed, depositing a further thirty feet of caliche on top of it. We had planned to pour a libation over the spot but discovered that we’d left the sixpack in Tucson. Or perhaps we’d drunk it the night before and didn’t remember. You don’t offer a friend warm beer on the desert, anyway.

I had never heard of Edward Abbey before I moved West from New York City in July 1979 and went to work on a drill rig on the high desert between Kemmerer, a coal town founded in 1897, and Evanston in southwestern Wyoming. That was the period of the so-called Sagebrush Rebellion, and the battle was fully joined between the energy companies and the environmentalists who were resisting what they called the rape of the West.

Ed had been fighting the miners, the riggers, the timber and lumber companies, and the ranchers all of his adult life, and now I was in the middle of it all. I discovered his books in the aisles of Sam Weller’s a few months after my arrival and brought home an armload. I started with Desert Solitaire—his wonderful (and best) book about several seasons working as the sole U.S. Park Ranger at Arches National Monument north of Moab—and went on to his volumes of essays and stories and The Monkey Wrench Gang. More than forty years later, I still read Solitaire once a year and browse the collections regularly. My country is the American West, Ed had written: all of it. It’s all down in the books, too.

Growing up in a family that divided the year between a large and handsome apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and a 225-acre farm in south central Vermont, I had an upbringing that was one-half deep country and one-half deep city. The country part of me won out, and since 1979 I have lived in small-town Wyoming surrounded by vast spaces of high sagebrush desert and ten- to twelve-thousand-foot mountains. I am at home in the back country, going horseback with a rifle in the scabbard under my leg and a good tent in my packs, and I wish to see the wild country protected and preserved—forever, if possible—from human development.

On the other hand, I appreciate and support most of what economic development there is in the big Western states, most of it related to various types of energy extraction and to ranching and agriculture. (The unspeakable tourist and recreational industry is another matter entirely.) The honest, industrious, indigenous Western culture I find compatible with the natural landscape, which it complements. It remains, as I understand it, essentially a pioneer culture.

Ed Abbey did not agree about this, though he did have friends among the ranching populations of Arizona, Utah, and elsewhere. He considered the vast majority of cattle and sheep ranchers with their generous federal leases parasites on the state and federal governments, on the taxpayers, and on the land and the rest of the natural world. Having spent my childhood among farmers, loggers, and other rural people, I have never been able to feel that way—a difference of viewpoint between us that disturbed me even before I met Ed. It seemed to me that to object to pioneer America as too humanized is to misunderstand the proper balance between the human and the natural worlds.

My grandfather Robert D. Williamson, born in 1874, grew up on a farm on the Michigan frontier that, in many ways, he never really left, despite having run away from home at the age of ten, put himself through the University of Michigan sleeping three to a bed, and gone on to become editor-in-chief of the Silver Burdett publishing house, based in Boston and afterward in Manhattan. All his life he was a habitual, almost compulsive reader of the lengthy series of frontier memoirs published by the Lakeshore Press; he introduced his grandchildren to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books, which I continue to reread to this day. To me, the frontier implies people and human civilization as much as the city does, only a great deal less of it and in better adjustment to each other.

In 1992 I was received into the Catholic Church, sponsored by a ranching couple in Kemmerer with whom I’d become close friends, and whose son was ordained by Pope John Paul II in St. Peter’s Basilica. Of all the many places I’ve lived, Kemmerer, population about three thousand, is the one I consider home. I’d already written the first two volumes of my Fontenelle Trilogy and was well into the final one when I became a Catholic. To anyone who knows Kemmerer, Fontenelle and it are one and the same place. I do not believe that Ed could have written anything like these novels—not that it would have interested him to do so, of course. His fiction concerns socially isolated individuals, alienated from the industrial world, whose sole commitment is to eco-warriors like themselves and to “the Earth,” which to them are all that is worth loving and fighting for.

“What else do we need?” is a question that Ed asks time and time again in his work. It is a position that I have often myself been tempted to take from frustration, disgust, and despair at the destructiveness, the vulgarity, the depredations, the increasing inhumanity, and the senselessness of the industrialized—and now post-industrial—world, but without being able to accept it finally as my own. Ed Abbey and the “monkey wrenchers”—the industrial saboteurs who were among his friends and account for many of his fictional characters—were, and are, people who make nature the measure of everything, including man. Temperamentally and now as a Catholic, I cannot do that, though I see as clearly as anyone that Homo sapiens has spent the past two centuries desacralizing the natural world and his own nature, and offending God in the process.

This philosophical stance has not always brought me peace of mind and equanimity on the question of man versus nature. The fact is that I love the American West—the land, the flora, the fauna, the traditional way of rural life, the people—with a jealous love. From my Vermont childhood on a two-track dirt road far back in the Green Mountains I learned to survey my own equivalent of what Faulkner called his postage stamp of ground in a spirit of fierce defensiveness that shades toward the offensive. The appalling plastic and featureless suburbs, annealing the former farm towns along the Front Range of Colorado into one massive urban sprawl extending from Fort Collins in the north to Pueblo in the south; the gilded plutocratic ghetto where hedge fund billionaires, money managers, members of the Federal Reserve Board, Silicon Valley CEOs, movie actors, Republican politicians, and other such postmodern savages disport themselves at the base of the Grand Tetons; the vast retirement cities of southern Arizona where executives go to drain the deserts of water, and consequently life, before they die—all this has often driven me into fits of monkey-wrench rage worthy of Abbey’s George Washington Hayduke and Doc Sarvis.

Still, there is hope. Humanity can never destroy the earth; it can destroy it only insofar as it exists for human purposes. As for the very real damage that humans do inflict on the earth, it is necessary to consider that it is impossible for humans or any other species to live in the world without altering it in one perceptible way or another.

The year Edward Abbey died, Bill McKibben published The End of Nature. By “the end of nature” he meant (and means)

that for the first time human beings had become so large that they altered everything around us. That we had ended nature as an independent force, that our appetites and habits and desires could now be read in every cubic meter of air, in every increment on the thermometer. . . . We are no longer able to think of ourselves as a species tossed about by larger forces—now we are those larger forces. Hurricanes and thunderstorms and tornadoes become not acts of God but acts of man.

Abbey had never gone so far, nor had his environmentalist companions in arms. Yet McKibben went further still. “We are different from the natural order, for the single reason that we possess the possibility of self-restraint, of choosing some other way. Which brings us again to politics, to the realm where we will make the collective decision on whether or not to restrain ourselves. . . . It’s not that it can’t be done.”

McKibben’s arguments for controlling and directing the impact human civilization has upon the earth, and the assumptions on which those arguments are based, are foundational to the current crusade against global warming: the industrial system was created by “us” two hundred years ago; “we” made a conscious and collective choice as a species to establish it; by doing so “we” made a fatal mistake for which we bear moral responsibility; but “we” can choose nevertheless to modify the system drastically, just as “we” chose to erect it in the first place.

Viewed in this way, industrial consumerism is the result of a social contract, similar to the one that established human society itself, according to Rousseau, though his theory has absolutely no basis, or even plausibility, in history.

The McKibben fallacy, which is the fallacy of the “net zero” campaign today, is a triple one. The first is the notion that societies are capable of a collective decision regarding the direction in which they wish to go. The second is that they are capable of knowing where they are going. And the third is that they have the ability to get there. The delusion that they can do any of these is responsible for 90 percent of what passes for rationalist social and political thought in our time, while bearing no relationship whatsoever to reality.

Just as the industrial system was never planned by individuals or societies, so it cannot be reversed, dismantled, or significantly modified by them. It was developed piecemeal by men who for the most part were not in organized collaboration with each other but worked separately, often unaware of the others’ activity. None could see far beyond the immediate consequences of his own work. Societies necessarily lack foresight according to their scale and the degree of their technological and social complexity.

We live in a liberal age, which implies, among other things, that we live in a highly moralistic one. It is among the many contradictions of liberal thought that, while liberals have always denied the possibility of collective guilt, today they recognize it everywhere in Western history and are fond of identifying examples of it. This tendency has developed to the point where progressive Westerners are questioning whether it really is a good thing that the human race should exist at all, given its history of living at the expense of other creatures and even inanimate objects.

Others, of a more moderate and generous temper, suggest that Homo sapiens would be a morally justifiable species had he gone into collective tribal conference in prehistoric times and decided against advancing from nomadic hunting and gathering to settled agricultural life. Here, of course, we see the McKibben fallacy at work again as an aspect of postmodern wisdom and enlightenment. It is not one that Abbey, or even his radical friends with Earth First!, thought to invent. It was left to a more advanced generation of liberal theorists to do that.

It is quite true that at one level industrialism makes no sense at all. It has done unfathomable damage to the natural world and thrown all of nature off balance and out of kilter, as Flannery O’Connor’s Misfit thought Christ had done. Moreover it is, indeed, “unsustainable,” as environmentalists say, depending on growth for the sake of growth, which Abbey called “the ideology of the cancer cell.”

On the other hand, it has brought humanity great material benefits, vastly improved its health, lengthened its lifespan, freed it to exercise its mental abilities, talents, and ingenuity on behalf of the arts and sciences, and provided it with the leisure for philosophical and theological pursuits. While it has been responsible for much that has been ugly, vulgar, dangerous, and deadly in the world, it has also produced much that has been majestic, beautiful, and sublime, including, for example, the twentieth-century ocean liner, a perfect example of the fusion of mechanical technique and the plastic arts. It has allowed man to be all he can be on another (though not necessarily a higher) plane of existence than in the pre-industrial era. The nature, power, and quality of the human mind made the modern industrial world inevitable, given the time and the circumstances necessary for men to develop and exercise the abilities of the race.

Romano Guardini, the Italian-born priest and theologian, argued in a luminous brief book, Letters from Lake Como, that the “old world”—the pre-industrial world in which human culture developed organically from the natural one, which ended roughly between 1830 and 1870—“was sustained by human beings and in turn sustained them. . . . They kept it alive in their hands. It was their work, expression, object, and instrument, all at the same time. That was culture, and what we still have in the way of culture today derives from it.” Yet

It is Christianity that has made possible science and technology and all that results from them. Only those who had been influenced by the immediacy of the redeemed soul to God and the dignity of the regenerate, so that they were aware of being different from the world around them, could have broken free from the tie to nature in the way that this has been done in the age of technology. The people of antiquity would have been afraid of hubris here.

“Only those,” he continues, “to whom Christian faith had given profound assurance about eternal life had the confidence that such an undertaking requires. But the forces, of course, have broken free from the hands of living personalities. Or should we say that the latter could not hold them and let them go free? These forces have thus fallen victim to the demonism of number, machine, and the will for domination.”

Now, twenty-one centuries after Christ, it is becoming clear that civilization as we know it cannot, and so will not, go on forever. Does this imply that it should never have existed at all? The question is an ahistorical, anti-philosophic, and anti-scientific one. Nothing is forever, including the universe—with the exception, for Christians and other religious believers, of the human soul and the celestial powers that be. Meanwhile, what is is better than what is not; what has been than what never was, and never will be.

Ed Abbey was a pagan, who welcomed what he recognized, quite correctly, as the return of paganism to the Western world.

“God? I think . . . who the hell is He?” he asks in Desert Solitaire. “There is nothing here, at the moment, but me and the desert. And that’s the truth. Why confuse the issue by dragging in a superfluous entity? Occam’s razor. Beyond atheism, nontheism. I am not an atheist but an earthiest. Be true to the earth.”

Paganism and the worship of nature have the attraction of obviousness and simplicity. But as Chesterton and Eliot said, having experienced Christianity the world has come too far and gained too much knowledge—even if most of it is forgotten—to return to the pagan one.

Edward Abbey would not have agreed with our modern nihilists that the human world should have stopped short at its hunter-gatherer stage and foregone, to begin with, “the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome.”

Nor would it ever have occurred to him to argue that the world would be a better place without people, who—as the most enlightened among contemporary environmentalists suggest—have a collective moral duty to commit species suicide and leave the earth to the animals, the insects, the trees, and the rocks. Ed liked women too much to have believed any such thing, for starters.