In the eulogy of Leo Strauss that I delivered in November 1973, shortly after his death, I said that I would leave to others “more detached and more objective, the judgment of Strauss’s place among the political philosophers.” That warning needs to be repeated in the light of developments in the near decade that has intervened. The interest in Strauss’s work has grown apace. A bibliography of the articles about him would be a substantial one. The character of his work, no less than its merit, has become matter of ever-increasing controversy with every passing year. But this, we must remind ourselves, has also been true of all the great figures of the great tradition that Strauss himself did so much to bring back to life. It would then be less than candid to conceal from my readers that I myself appear to be at or near the center of the disputations about Strauss. Anything I write should then be taken with all the caution with which one approaches the views of a partisan.

Readers of the January 22, 1982, National Review will be aware that I was roundly abused by Walter Berns for “presenting [myself] as the chosen spokesman for Leo Strauss.” I was not in the least aware of having done any such thing. Certainly I did not see myself as “speaking” for Strauss by writing about him—and interpreting his work—more than I had “spoken” for Abraham Lincoln, for example, in writing about him. Nor did I think that I had written differently about Strauss than Strauss himself had done about the political philosophers before him. In an essay entitled “In Defense of Political Philosophy” published in that same issue of National Review I had written:

Leo Strauss’s life and work had a motive that was not less political than philosophic. The political motive was to arrest and reverse “the decline of the West.” That decline consisted in the West’s loss of its sense of purpose. It no longer believed in its purpose, because it no longer understood that it had a purpose.

In this I thought I was merely repeating thoughts encountered many times in Strauss’s writings, as for example the following from the Introduction to The City and Man (1963):

The crisis of the West consists in the West’s having become uncertain of its purpose. The West was once certain of its purpose—of a purpose in which all men could be united, and hence it had a clear vision of its future as the future of mankind. We do no longer have that certainty and that clarity. Some among us even despair of the future, and this despair explains many forms of contemporary Western degradation.

Walter Berns, after denouncing my presumption, declares unhesitatingly that

Strauss did not believe he, or political philosophy could save Western civilization (or reverse “the decline of the West”). It is precisely hopes of this kind that distort the quest for truth. Eternity, not history, is the theme of philosophy, which Strauss believed, must beware of wishing to being. Jaffa, like Marx, wants to change the world, not to interpret it; he does nothing but edify.

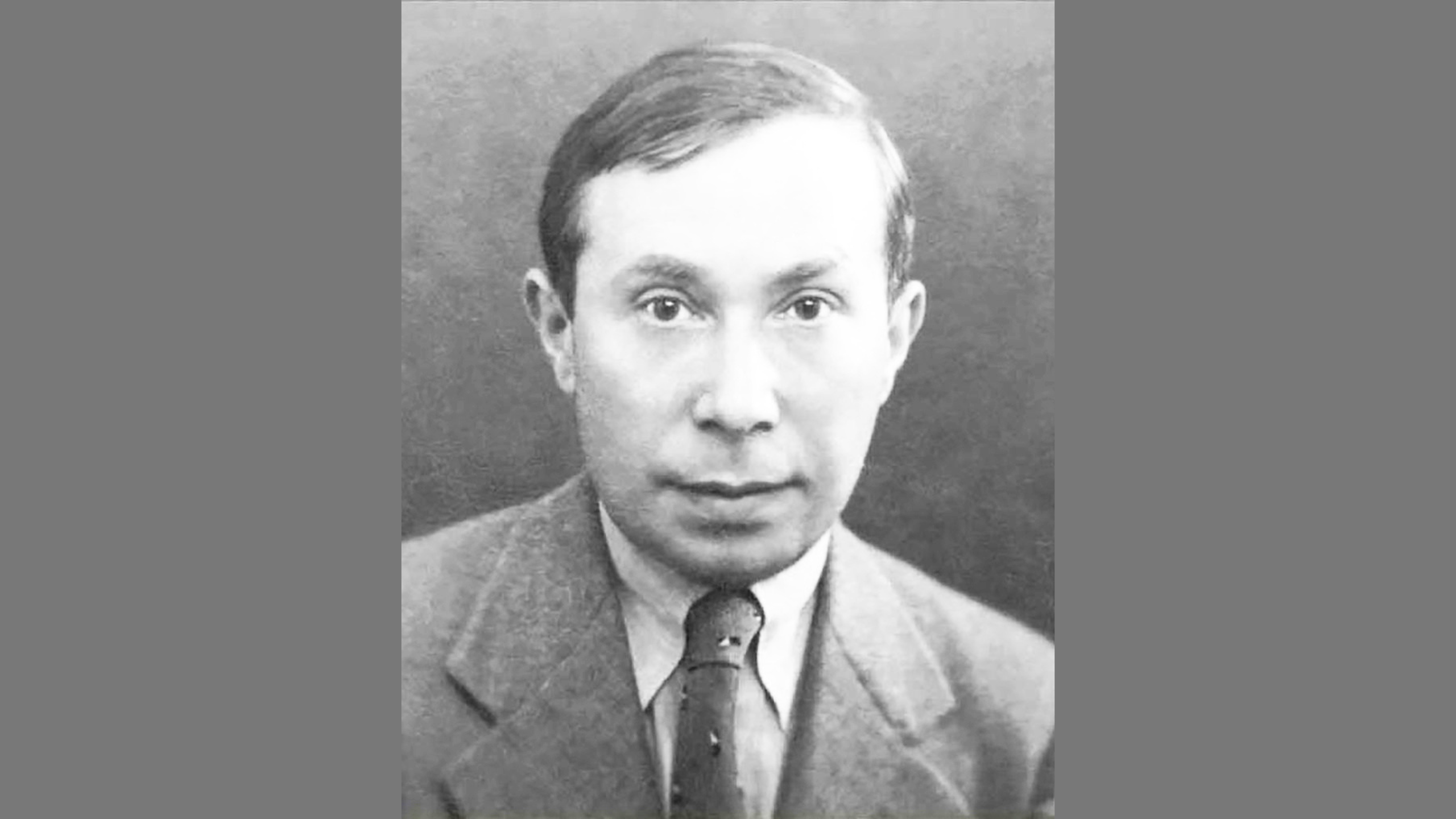

In the revised and enlarged edition of On Tyranny, also published in 1963, Strauss included a forty-five page critique of his interpretation of Xenophon’s Hiero by Alexander Kojeve, whom Strauss regarded as the most competent philosophic interpreter of Hegel. Kojeve (nee Kojevnikoff), originally a refugee from the Bolshevik revolution, was a French civil servant, and one who, if not strictly speaking a Stalinist, did not object to a Stalinist regime. He believed that a homogeneous world state, ruled by someone like Stalin, was inevitable on the basis of the dialectic of world history, and for that reason desirable. It was from this perspective that he criticized—and rejected—Strauss’s understanding of tyranny in On Tyranny. Whatever the defect of Kojeve’s political philosophy, he made absolutely clear Strauss’s disagreement with him, concerning both the necessity and the desirability of that “end of history” that Strauss had identified with the decline of the West. Strauss’s thirty-seven-page “Restatement,” in reply to Kojeve, completes what may well be the most philosophically competent intellectual confrontation of our times. It is sufficient to note here that, had Strauss resigned himself to the “decline of the West,” as Walter Berns says that he did, he neither would nor could have written his “Restatement.”

Berns says that I am “like Marx” in wanting to “change the world” rather than “to interpret it.” He accepts Marx’s dichotomy, in the theses on Feuerbach, between “change” and “interpretation.” He pretends not to notice the difference between that kind of change which aims to prevent the destruction of decent constitutional regimes, and their replacement with the homogeneous world state, and its opposite. Yet Walter Berns himself, in the late 1950s, wrote a brilliant essay entitled “The Case Against World Government,” which was precisely in the service of that philosophic understanding of politics, for which he now denounces me as being “like Marx.”

In “What Is Political Philosophy?” Strauss wrote that “All political action aims at either preservation or change. When desiring to preserve, we wish to prevent a change to the worse; when desiring to change, we wish to bring about something better.” Thought about better or worse necessarily implies thought of the good. Political philosophy clarifies the opinions of the good implicit in the political actions of men, and clarifies them in such a way as to replace these opinions with genuine knowledge. Moreover, Strauss says, “political philosophy deals with political matters in a manner that is meant to be relevant for political life; therefore its subject must be identical with its goal, the ultimate goal of political action.” Political philosophy is thus meant to guide political life, in the light of its ultimate goal, “the good life,” or “the good society,” which is “the complete political good.” In this, Strauss certainly followed Aristotle, who criticized Plato’s idea of the good, as being insufficiently “relevant for political life.” And he also followed the Aristotle who declared near the beginning of the Nicomachean Ethics that the end of political philosophy was “not knowledge but action.” Aristotle also declared (in Book II) that political philosophy “does not aim at theoretical knowledge . . . for we are inquiring not in order to know what virtue is, but in order to become good, since otherwise [our inquiry] would have been of no use.” It is for this reason, Aristotle proceeds, that “we must examine the nature of actions.” We must examine them, in order to know “how we ought to do them.” Clearly, if Walter Berns thinks that wanting to know about actions, for the sake of knowing how to do them, as distinct from the purely theoretical exercise of knowing how to interpret them, is being “like Marx,” then Aristotle, not less than Strauss and Jaffa, falls into that category.

Berns, in the context of this stricture, says (as we have noted): “Strauss believed [philosophy] must beware of wishing to be edifying. Jaffa . . . does nothing but edify.” Now the last two sentences of Thoughts on Machiavelli are as follows:

It would seem that the notion of the beneficence of nature or of the primacy of the Good must be restored by being rethought through a return to the fundamental experiences from which it is derived. For while “philosophy must beware of wishing to be edifying,” it is of necessity edifying.

The restoration of the idea “of the beneficence of nature,” which may alternatively be called the restoration “of the primacy of the Good,” by a “return to the fundamental experiences from which it is derived” is as good a summary statement of the intention of Leo Strauss’s life work as I can imagine. Strauss thought that the fundamental human experiences had become almost inaccessible, because of what modern science, modem technology, and modern philosophy had done to obscure and distort those experiences. He sometimes compared modern life to a cave beneath the “natural” cave represented in Plato’s Republic, and he compared his own work of philosophic recovery to an ascent to the natural cave. Nevertheless, this return was not in the service of understanding the truth about those experiences in the light of “Eternity” alone. In the Introduction to The City and Man he spoke of the “return to classical political philosophy”—which provided access to those “fundamental experiences”—as being “both necessary and tentative or experimental,” as follows:

Not in spite of but because of its tentative character, it must be carried out seriously, i.e. without squinting at our present predicament. There is no danger that we can ever become oblivious of this predicament since it is the incentive to our whole concern with the classics.

Let us repeat that, according to Leo Strauss, “our whole concern with the classics” was a hope that, according to Walter Berns, is “precisely”of the kind that distorts the quest for truth. Strauss did here warn against “squinting at our present predicament.” What he meant by this, I am confident, was that—to use his oft-repeated dictum—we must understand the classical texts as their authors understood them. We must, in this, exclude everything peculiar to our situation, but alien to theirs, from the work of interpretation. But the “fundamental experiences” to which he referred at the end of Thoughts on Machiavelli were of course fundamental human experiences, experiences of the human condition qua human. At issue is the question of whether there is a human condition intrinsic to man’s humanity, as distinct from an infinite number of possible human conditions, such as might or might not be thrown up by history, necessity, or chance, from the void of an unknowable universe. Strauss never, so far as I can tell, doubted that all possible human conditions might be denominated human. That implied that the distinctively human underlay all its possible manifestations. While he called the “return” to classical political philosophy “tentative and experimental” he also called it “necessary.” This implied that there was a necessity underlying the possibility of this return. Such a necessity was constituted by a nature that was “everywhere and always,” a nature that determined, what was intrinsically just and good.

When Strauss, at the end of Thoughts on Machiavelli, said that philosophy must beware of the wish to be edifying, he was quoting Hegel’s Phenomenology. Although Strauss agreed with Hegel—as far as he went—Strauss himself went farther. He corrected Hegel’s thought by adding to it. Walter Berns fails to notice Strauss’s addition, which is that philosophy “is of necessity edifying.” When therefore, Berns, in his role as Inquisitor, accuses me of the ultimate heresy, he says that “Jaffa . . . does nothing but edify.” In so doing, however, he pays me a compliment as hyperbolic as the condemnation he intended.

The conviction that philosophy is intrinsically edifying is at the heart of that idea of natural right which is ultimately indistinguishable from the idea of political philosophy itself. Philosophy is intrinsically edifying because progress in wisdom is possible, even when wisdom itself appears to be always beyond our grasp, even when opinion about the whole seems unlikely ever to be replaced by genuine knowledge of the whole. Although “we know that we know nothing,” there is a sense in which we know something about the whole, however incomplete and inadequate. If I understood him aright, Strauss—like Socrates—always rejected Meno’s rejection of the Socratic quest. When Socrates convicted Meno of ignorance of virtue, Meno wanted to abandon the quest for virtue, on the ground that his ignorance appeared to be so complete as to provide no basis upon which to recognize the truth, even if he were to discover it. In this Meno seems to have anticipated certain popular opinions associated today with Nietzsche and Heidegger. Certainly, Meno’s despair would explain Meno’s degradation. It was in this context that Socrates—or Plato—introduced the doctrine of learning as recollection. That doctrine is of course not a solution, but only a reformulation, of the problem, since it leaves us with the conundrum of how and when the soul which recollects first learned what it recollects. But that we can learn somehow, and even learn something about the highest things, the things upon which we can confidently ground our life and work, is a conviction—a faith perhaps, but a rational faith—upon which the natural right tradition is founded. I believe that it is upon the rock of this conviction that the work of Leo Strauss stands foursquare.

The remark about philosophy and the edifying, which appears at the end of Thoughts On Machiavelli, is repeated by Strauss near the end of “What Is Liberal Education?” This is the first essay in Liberalism Ancient and Modern. It belongs to one of many passages of surpassing beauty that one comes upon in the writings of Leo Strauss, one of many in which, in reflecting upon an experience easily accessible to everyone, Strauss has touched, and touched us, with that kinship with the divine which is our birthright:

Philosophy, we have learned, must be on its guard against the wish to be edifying—philosophy can only be intrinsically edifying. We cannot exert our understanding without from time to time understanding something of importance; and this act of understanding may be accompanied by the awareness of understanding, by the understanding of understanding, by noesis noeseos, and this is so high, so pure, so noble an experience that Aristotle could ascribe it to his God. This experience is entirely independent of whether what we understand primarily is pleasing or displeasing, fair or ugly. It leads us to realize that all evils are in a sense necessary if there is to be understanding. It enables us to accept all evils which befall us and which may well break our hearts in the spirit of good citizens of the city of God. By becoming aware of the dignity of the mind, we realize the true ground of the dignity of man and therewith the goodness of the world, whether we understand it as created or as uncreated, which is the home of man because it is the home of the human mind.

Harry V. Jaffa was a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College and Claremont Graduate University, as well as a Distinguished Fellow of the Claremont Institute.