Margaret Canovan sustains, as do girders a building, throughout the entire development of her argument, that a key to Chesterton’s mind was his hostility to the clerisy of his times. Chesterton scoffed at “intellectuals.” Mrs. Canovan points to the oddity of Gilbert Keith Chesterton as a child of the upper-English middle class, in no sense either aristocrat or proletarian but comfortably Edwardian and even Victorian in his origins and in his style of life, who identified himself fiercely with the aspirations, as he understood them, of the poor of England.

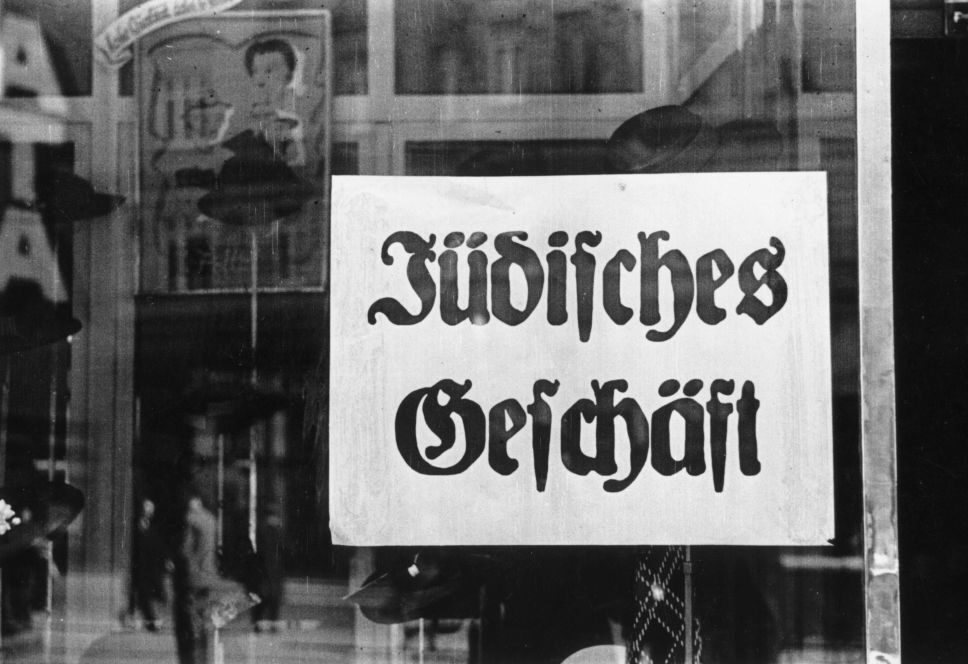

Abominating all forms of socialism and communism; insisting that he was a liberal although all liberals had abandoned liberalism; rejecting, often with violence and once with ill-concealed petulance, all forms of Burkean conservatism (no reverence for the rich, even the landed rich, in G. K. C.), Chesterton could find no political home in the England of his day. Negating all forms of “social reform” as coldly calculating in their goal of enslaving the poor or as mindlessly stupid, Chesterton set himself against Reformers and Eugenicists and raised the flag of “Beer and liberty versus Soap and Socialism.”

An adamantine simplicity suffused G. K. C. He was—if I may gloss the text of Margaret Canovan—a man with the wondering and enchanted sensibility of a child at Christmas in whose head was lodged a mind of astonishing and even frightening genius. Chesterton is the old pub down the street against the pretentious club of the rich; Chesterton is the corner grocery store against the chain; Chesterton is neighborhood against town, town against city, city against state, land against industry, poor against rich, traditional wisdom against lettered arrogance, war against a peace that settles servility upon the soil of civilization. Chesterton is eloquence given the dumb; elegance, the awkward; erudition, the unlettered. He thunders in the name of a humanity that dared not, even could not, utter its own name in the soulless squalor of industrial blight and ugliness.

Chesterton is eloquence given the dumb; elegance, the awkward; erudition, the unlettered.

Chesterton, the populist, fiercely set himself against every scheme concocted to “better” the poor. In arguing for the romance of domesticity, he opposed all laws which gave the agents of the state the presumed right to enter into the slums and dictate health conditions to their “inferiors.” The solution: abolish the slums! The famous peroration of his What’s Wrong With the World (the most elaborate political syllogism known to this writer) has Chesterton launching a revolution in the name of the right of a little urchin of the slums to keep her red hair against the scissors of the state that would cut it off because she might have lice. It was typical of Chesterton’s cavalier and even sloppy scholarship that in this case he got the facts wrong even though nobody before him or since has articulated the principle with greater brilliance. Canovan is not unaware of the defects of her subject.

The poor want a house of their own, not one groaning under the criminal usury of the banks. They want work as an extension, usually, of their own hands. They want a little kingdom in which to exercise the arts of domesticity, “the poetry of limits,” which involve rearing children in the knowledge and love of God. Such was Chesterton’s essentially simple political philosophy. This goal annealed him in a tradition that ran through Cobbett back to the High Middle Ages. But, Canovan asks, did Chesterton’s long romance with the downtrodden of England correspond to reality? Where were the people that their spokesman espoused? Her judgment is that such “people” did not exist in large numbers in England but that they did people the minds of a significant number of middle-class romantics who thought, as did Chesterton, that the woes of the times could be laid to industrial society. Chesterton’s Distributist Movement displayed all the crankiness its founder had already condemned in similar “back to the farm’’ and “back-to-the arts and crafts” and “bake your own bread” rages propounded earlier in the name of utopian socialism or romantic gothic medievalism. Chesterton was bigger than his own troop. He was aware that such idealism could be harnessed by conventional conservatism as a welcome instrument in keeping the Establishment in existence: these fads drain off support to the Left. Some of Chesterton’s novels center around this danger, as Canovan demonstrates with considerable critical acumen.

The author speaks of Belloc’s influence on Chesterton. After all, Hilaire Belloc had tried his hand at party politics, had served twice in Parliament, and had come away disgusted with the charade. Chesterton learned from Belloc the wisdom of never putting your trust in political parties. But the alternatives to the going system, either a populist democracy or a popular monarchy, seemed as distant then to the Chester-Belloc as they seem distant to us today. Belloc never shared Chesterton’s romance with the “little people,” possibly because he knew so many of them. Chesterton thought that the poor of his time really wanted a house and a cow and three acres. But Belloc, all along the spectrum of his life, doubted that men really wanted liberty after all; the ideal was too dim; too much time had passed since the Reformation; slavery would probably settle itself upon us in one or another form. This Gallic irony, bordering but never descending to the cheapness of cynicism, was vintage Belloc. It had little to do with the hearty romance Chesterton carried on with “the poor” until he died in 1936. Optimism was an act of faith for Belloc; for Chesterton, optimism was a condition for existence.

From this romance with God’s lowly, Canovan raises the question of Chesterton’s relation to the Catholic Church. This wildly chaotic, almost anarchical, white banner in which the humble of the world rise and throw off the shackles of industrialized misery has little to do with the severe authoritarian political philosophy marking the Catholic Right in Europe. So insists the author. She is dead on target concerning French Traditionalism and “integrism.” Chesterton never would have been comfortable there, but he would have found a home in Spanish Carlism—about which he knew nothing at all. Therefore he could permit himself the luxury of inventing an English version of Carlism: a land mastered by small farmers, artisans, reposing on prescriptive law, venerating the Church, and governed by a popular king whose title rested on familial legitimacy and thus reflected the legitimacy of every father in his family against all the laws and philosophical nostrums of this world.

Canovan could not develop the issue too deeply because it fell outside the limits of her study, but she does point to G. K. C.’s sympathy with the Thomistic tradition and his antipathy for the Augustinianism and the Platonism hovering behind its skirts. Chesterton’s Saint Thomas Aquinas was hailed by both Maritain (who did not like Chesterton) and by Gilson (who did). The Thomistic emphasis on sensation as the root of human knowledge; the Thomistic insistance on common experience rather than privileged intuition as the source of wisdom; the Thomistic celebration of the goodness of creation and of the solidity of the world (read Chesterton on Stevenson’s Treasure Island in his remarkable The Victorian Age in Literature), confirmed Chesterton in what he already believed. As an adolescent he had fought free from the temptation to doubt the existence of an external world. His subsequent life was a long song of praise to existence. But Canovan’s suggestion that Chesterton grasped only one half of Catholicism, that is, the Thomistic, and not the other unworldly half, the Augustinian, is dubious in its formulation. The Thomistic half is official doctrine and the Augustinian half perdures to the degree to which it has been absorbed into the Thomistic half. If Chesterton seized on Thomas, then Chesterton embraced the full Catholic spirit. Saint Thomas is “The Common Doctor.” There are no heresies that grow out of the reading of Aquinas. The same cannot be said of Augustine.

Canovan has sketched splendidly the Chesterton who was a populist. But Chesterton was so many other things as well. The observation implies no criticism: Canovan is aware of the gargantuan proportions of her subject. Chesterton, for example, was a first-rate literary critic. He was an even better metaphysician and theologian, without garnishing his signature with the alphabet soup of degrees that usually goes after the names of those pretending to such a competence. Chesterton’s sense of paradox, as Hugh Kenner suggested in his little book on the same topic, reflects the Thomistic analogy of being. Any man who could speak of the Blessed Trinity as a “Holy Company” and who could state quietly that “we trinitarians have known that it is not good for God to be alone,” and to write these words as he contemplated the vast deserts of Africa and the negations of Islam, is a man impossible to explicate in one study dedicated to one admittedly important aspect of his thinking. A gigantic man, physically as well as spiritually, Gilbert Keith Chesterton will perforce be approached from the prejudices and predilections of those who first come to know his thought. (Chesterton, of course, is read everywhere today in the Christian academic underground even as he is ignored officially everywhere.)

He was neither a politician, a novelist, a man of letters, an historian, a polemicist, a poet, or anything else. He was all of these things, but none of them defines him. I rather imagine that he was a latter-day Doctor of the Roman Catholic Church.

Frederick D. Wilhelmsen was a Catholic philosopher and a professor at the University of Dallas.