“If wishes were fishes, we’d all cast nets.” The folk wisdom in the saying is straightforward: if wishing had any power to truly shape reality, then no activity would be more important than wishing. But it doesn’t, and it isn’t, so stop wishing that things were different and focus on the task at hand (like catching ordinary fish to eat or sell).

Notwithstanding this wisdom, wishing plays an important role in folk stories from time immemorial down to our own era. Many of these tales are cautionary: the fisherman’s wife in Grimm’s tale gets hooked on wishing for ever greater power and ends up losing everything, and when the monkey’s paw grants its wishes, it is always by means of calamity. In Hollywood, from Geppetto’s wish upon a star to Jim Carrey’s Bruce Almighty, the end is usually happier, even if it involves ultimately abjuring the wish’s power. And from a modern psychological perspective, speaking wishes aloud is preferable to repression, whether because doing so is the first stage in goal-formation that leads to the casting of real nets, or, contradictorily, because doing so drains unattainable or forbidden desires of the mythic power they assume in silence.

That’s an account of wishes that begins and ends with the mind of the wisher. What, though, if our deepest wish is for love, indeed, for a particular object’s love? An intimate encounter with another necessarily involves their wishes, and not just ours. Is there a way to make a story premised on such a wish end happily? Or will the monkey’s paw inevitably get its revenge on any attempt to wish away another’s will?

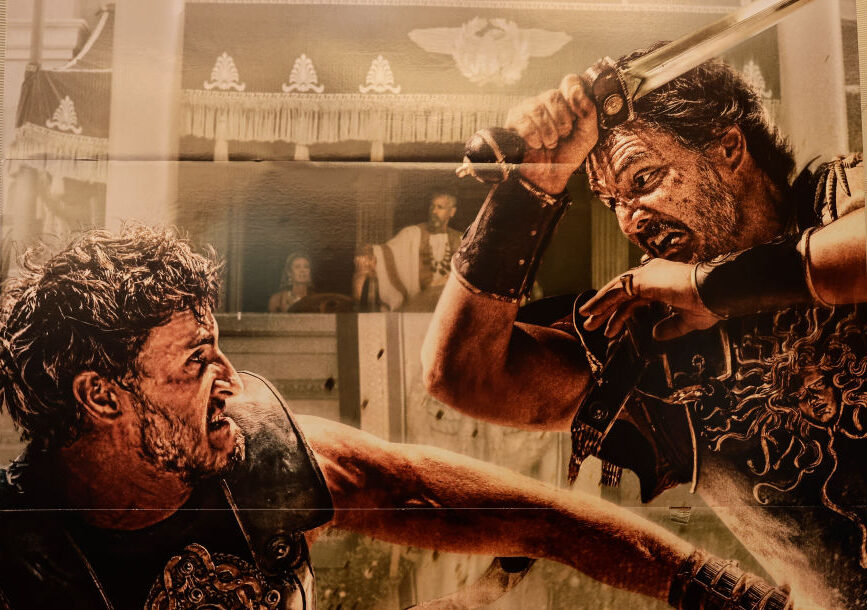

George Miller’s latest film, Three Thousand Years of Longing, announces from the get-go both that it is true and that it is a fable, told as such because, ironically, it’s the only way it will be believed. Its author within the film’s frame is Alithea (Tilda Swinton), a narratologist who, at an academic conference in Istanbul, begins to show signs of either serious mental instability or encounters with the uncanny. First, a trollish figure approaches her at the airport, tries to take her luggage cart, and when rebuffed shimmers and vanishes. Then, in the middle of her presentation to a capacity crowd in an auditorium, a pale, crowned figure appears in the crowd, opens his mouth, and appears about to devour the entire podium when she blacks out.

As Alithea explains to her concerned colleagues, she has long been prone to an overactive imagination, the inhabitants of which from time to time invade her waking world. Later, we learn that in her lonely, bookish youth, she created a companion for herself, a boy of words whom she could feel emerging from the confines of her written stories to listen to her, put his arm around her shoulders, and comfort her in her times of trial. He only ceased to visit her when she threw his book on the fire, not merely putting aside childish things but immolating them.

It is fitting, then, that her most consequential encounter with the uncanny involves a spirit of fire. After purchasing a partly melted antique glass bottle at a shop in the bazaar, she takes the object back to her hotel room and, cleaning it in the sink, releases the stopper and with it the Djinn who resides within (played by Idris Elba). Once they have figured out how to communicate (they speak at first in Homeric Greek, but the Djinn learns English quickly from a few minutes’ interaction with a television and a laptop computer), they settle down to the business of wishing.

Only Alithea won’t get down to business. She knows the stories too well, knows that djinn are tricksters and that wish stories are often cautionary tales. What she wants, but needn’t wish for, is for the Djinn to tell her his story, which he does.

The film then enters the world of those stories, narrated by the Djinn, which provide Miller with the opportunity to show off what he can do with CGI, and he does manage to conjure up a handful of minor miracles. An instrument that King Solomon plays, which accompanies itself with additional wooden hands that adorn its neck, is particularly worthy of note, and whatever combination of digital and practical effects created them, the worlds conjured up in the Djinn’s stories are both splendidly sumptuous and refreshingly unapologetic in their old-fashioned Orientalism. But they also have an indelible aura of unreality that, while true to their magic-realist literary roots, foreshadows a major problem for a story that is supposed to be about love, which is what the Djinn declares to be his essential subject.

In his first tale, the Djinn is the short leg of a love triangle, the lover of the Queen of Sheba, who is half-djinn and half-human and who is beguiled by the human but distinctly wizardly King Solomon, the first to imprison the Djinn within a bottle. This is not a story of wishes, the magical satisfaction of desire—Solomon has all the magic he needs already, and Sheba all the desire—but of the imprisonment of desire through human cunning. The Djinn waits over two thousand years for release, until Gülten, an Ottoman slave girl, finds his bottle. In her story the Djinn’s role is to be not a lover but a go-between, facilitating the slave girl’s desired romance with the crown prince. This is a classic cautionary wish tale, in which every granted wish (to win the prince’s favor, to conceive his child) leads to deeper misery and ultimately death, but as the Djinn is no trickster it is unclear what force propels the story down its doomy path. And while we’re getting a sense of the dangers of desire for an individual, we don’t yet feel it as something that flows between two people.

When Gülten dies without making her final wish, the Djinn is trapped in a kind of limbo, neither in his bottle nor in the world, reduced to a disembodied and increasingly desperate observer. Meanwhile, absent his influence desire becomes deranged. The heir to the Ottoman throne grows into a murderous monster whose soul can only be salved by (of course) an exceptional storyteller, while his brother is sequestered in a fur-lined prison with a grossly obese harem. Their own mother built this artificial womb to keep her younger son from the reach of his brother’s bloody hand and populated it with these living versions of a Paleolithic Venus figurine. So it is hardly surprising that even when he takes the throne he remains a helpless child, or that, when one of the harem accidentally brings the Djinn back to corporeality, she promptly imprisons him again. Her role is to wield imperial power and satisfy the nominal ruler’s infantile desires; any wishes of her own would only be a distraction.

The Djinn’s final story takes place only a few hundred years later and involves an obvious precursor to Alithea herself: Zefir, the neglected wife of a nineteenth-century merchant with an insatiable curiosity that the Djinn delights to satisfy. He becomes her lover as well, but as her horizons expand she grows increasingly frustrated with the limited confines of her world. Yet a final wish would sunder her from her magical lover. Faced with the torture of this dilemma, the Djinn retreats over and over to hide in a bottle, until, at the climax of one argument, Zefir wishes she could forget him, and does, leaving him imprisoned once again until Alithea frees him.

This story perfectly tees up Alithea to finally make a wish of her own. She plainly sees herself in Zefir, and she already knows herself to be comfortable with solitude and the company of books. She had a husband once, but they split after his infidelity, which might have been triggered in part by her own remoteness; in any event, she takes his departure and her return to solitude as a relief. The only thing she could possibly desire is desire itself. So that is her wish: that the Djinn fall in love with her as he did with Zefir, and with Sheba before her.

Her wish is his command, and soon she and the Djinn are back in London snuggling in her improbably opulent townhouse and defying her improbably overtly bigoted neighbors. And then, just as their romance has started to get going, the rules of the game change. One day she comes home to find the Djinn huddled on the floor against a wall, frozen still, as if his elemental fire had gone out. It seems the Djinn can’t live as a permanent captive to a mortal’s wish, and she realizes with a flash that the love she has received from him, being commanded, cannot be true. So, loving him as she does, she wishes for his freedom, and loses him.

The moment should be heartbreaking. I’ve seen a version of it before, at the end of an Israeli movie called I Love You, Rosa, whose lovers, finally about to be united, are sundered by the very law that brings them together—the law of levirate marriage—because Rosa will not accept a love that is commanded rather than freely chosen. To have her, her young lover, Nissim, must release her from that bond, but if he does so she will be forbidden to him forever. But Nissim and Rosa are human; we’ve seen their unlikely love grow over years, and the legal trap that springs the end has been wound the whole film through. The shift at the end of Three Thousand Years of Longing, by contrast, is terribly abrupt, and it serves only to underline the fundamental dissatisfaction at the core of the story: that Alithea’s lover is literally fantastic.

Alithea has only one wish: to experience love such as the Djinn described in his stories. Was that wish granted? Perhaps—but only if those loves were as solipsistic as the one we see her experience, with a compelled lover who may (if we take seriously her story about her fictional childhood lover) be a figment of her imagination. If she knows now that whatever this was, it wasn’t truly love, then what has she experienced but illusion? From that, we would expect one of two things to happen: either, going forward, stories would no longer work the magic on her imagination that they did before, in which case her story would be another tragic cautionary wishing tale; or, in a more typical Hollywood ending, thanks to the experience of desire in the allegorical form of the Djinn, she would finally emerge from her isolation into a new engagement with the real world, and the opportunity to be part of a story that isn’t all on the page or in her head.

Miller’s film, however, prefers to stay in the land of wish fulfillment. Far from being disillusioned with the power of stories, Alithea sits down with a smile to write the one we’ve been watching. And far from opening up to new experience of the real world, she is rewarded for her fidelity to the world of imagination by the Djinn’s return, now a free visitor rather than a compelled lover. It’s supposed to be a happy ending, but I couldn’t help feeling the same contempt Rooney Mara’s character expressed for her ex-husband, played by Joaquin Phoenix, in the film Her, when she found out that his new love with whom he seemed so happy was an artificial intelligence. And that AI showed more signs of authentic selfhood, of expressing its own needs and desires, than the Djinn ever does. Watching Alithea in the final shot, walking beside her perfect, magical lover, I couldn’t help feeling that she was even more alone than she was when the film began.

***

Shakespeare frequently made use of folk stories and motifs for his plays, particularly for his comedies and romances—think of the casket test that Bassanio must pass to win the hand of Portia in The Merchant of Venice, or the cartoonishly evil stepmother who springs the plot of Cymbeline. But in All’s Well That Ends Well, which I saw again last year in a marvelously faithful production at the Stratford Festival, Shakespeare takes the extraordinary risk of imbuing a folk tale of wish fulfillment with a fully realized psychology. The result is a discomfiting but ultimately deeply moving meditation on desire, and the power and peril of wishing too hard.

Like Alithea, though much younger, Helen (Jessica B. Hill), the heroine of All’s Well That Ends Well, is a learned woman who has spent a lot of time in her own head among the dreams that live there. She’s the orphan daughter of a renowned doctor who was raised by the Countess Rossillion (Seana McKenna), but unlike Alithea’s boy of prose, Helen’s imaginary boyfriend is the all-too-flesh-and-blood Bertram (Jordin Hall), the son of the Countess who, as the play opens, has just come into his title with the death of his father. (Director Scott Wentworth opens the play on the silent funeral, which sets a somber tone and affords costume designer Michelle Bohn the opportunity to swathe the cast in elegant Edwardian black.)

As Hamlet is to Ophelia, Bertram is out of Helen’s star, and that knowledge is the subtext of the free and confident sexual banter she engages in with Bertram’s braggart soldier friend, Parolles (Rylan Wilkie), which first introduces the audience to her, establishing at once that she is no wallflower but a woman of spirit. That’s important for us to know before her scene with the Countess, where the subtext becomes text, and she desperately tries to avoid either the suggestion that she and Bertram are siblings or an admission of her desire that they be something more. Cornered by her adoptive mother, she admits to her love for her sometime brother, and, though the Countess seems far from dismayed (indeed, throughout the play all the older, wiser characters are consistently on Helen’s side in everything), Helen clearly thinks that she needs to do something more to be a plausible match for her beloved.

And so she hatches a plan, one that she only articulates in part even to those who love her most completely. The king of France (Ben Carlson), as it happens, is then on his death bed, wasting away from a fistula. She, from her father, has an elixir that will effect a complete cure. Her plan, which she executes to the letter, is to travel to Paris and cure the king—extracting from him before she does so a promise to give her the hand of any man in the kingdom as a reward.

The sequence, which takes us through the end of Act I, is a delicate one, in which the audience must not see either of two things lest the play fail. On the one hand, we cannot notice that Helen has never asked Bertram if he loves her. On the other hand, we must also never notice any definitive sign of more-than-sibling affection between the two. If we see either—either that Helen hasn’t asked because she knows (or fears) that she would be rejected and needs to trap her lover like prey to win him or that Helen hasn’t asked because she feels his affection clearly and so expects that she wouldn’t be rejected except for her lowly station, which the king can cure as easily as she can cure him—then the twist that opens Act II will not land, and neither will the play. To wit: when the king is cured, and Helen, given a choice of all the eligible bachelors of the court to wed, chooses none but selects Bertram instead, the young man is appalled—and Helen realizes in an instant that she has made a terrible mistake.

I give full credit to Wentworth’s direction and Hill’s performance for the fact that the key moment comes off masterfully. Helen is appropriately mortified by Bertram’s furious objection, and sees what a fool she’s been—but we are mortified along with her rather than standing beside tut-tutting at her foolishness. And in this moment we also understand and can even empathize with Bertram, whose warm smiles at the prospect of his sometime sister making such a fortunate match turn to horror when he realizes she means to match with him, and never broached the subject.

Bertram then says a number of terrible things, insulting Helen’s birth (which likely played differently in Shakespeare’s day than it does in ours) and protesting that he “cannot love her nor will strive to do’t,” but the heart of his objection is in his first cruel response: that in “such a business” he be allowed to use his own eyes. That’s not just an insult to Helen’s looks, though. It’s impossible to understand his response apart from his gender; many a questing knight has won a princess as his reward, but Bertram is a man, not a maiden—nor a djinn. He expects to be able to choose.

And so, within the confines of his obligation to his sovereign, he does. The king commands him to wed, so he weds Helen—but refuses to bed her, and departs at once with Parolles for wars in Italy. Moreover, he promises in letters never to return to France while his wife lives, nor to accept her as a wife unless she can get his family signet ring from his finger and show him a child begotten of him on her. The signet and the child are, again, the stuff of folklore, and possibly an echo of the biblical story of Judah and Tamar (another levirate marriage tale with a sprung trap), who may have given Helen a clue about what trickery she must descend to in order to surmount this latest, seemingly impossible trial. But before we get to that, there is an additional delicate moment to surmount: the newlyweds’ leave-taking.

Bertram is eager to fly, and Helen is trying to play the submissively obedient wife, which does nothing to soften her spouse’s iron-barred heart. Before he goes, though, she asks one boon:

Something, and scarce so much; nothing indeed.

I would not tell you what I would, my lord.

Faith, yes:

Strangers and foes do sunder, and not kiss. (2.5.83–86)

There’s no stage direction, so again I need to give credit to Wentworth, Hill, and Hall for the subtle complexity of the kiss they chose to perform at this point. Bertram, with some reluctance, grants Helen her kiss, and she takes it, hungrily. He responds—and then breaks, flustered and troubled, and flees. This could play as Bertram’s disgust at the lingering incestuous overtones of their union, or, more obviously in harmony with the text, as his anger at being caught, even fleetingly, by the charms of a woman he sees as an unworthy gold digger. But it read differently to me, more in harmony with his first objection insisting that he make his own choice. What he’s responding to is Helen’s desire itself, its fierceness and its sincerity, and that desire itself is what he then flees from, as if he fears its power will unman him. And so to the wars, where that fate, at least, he need not fear.

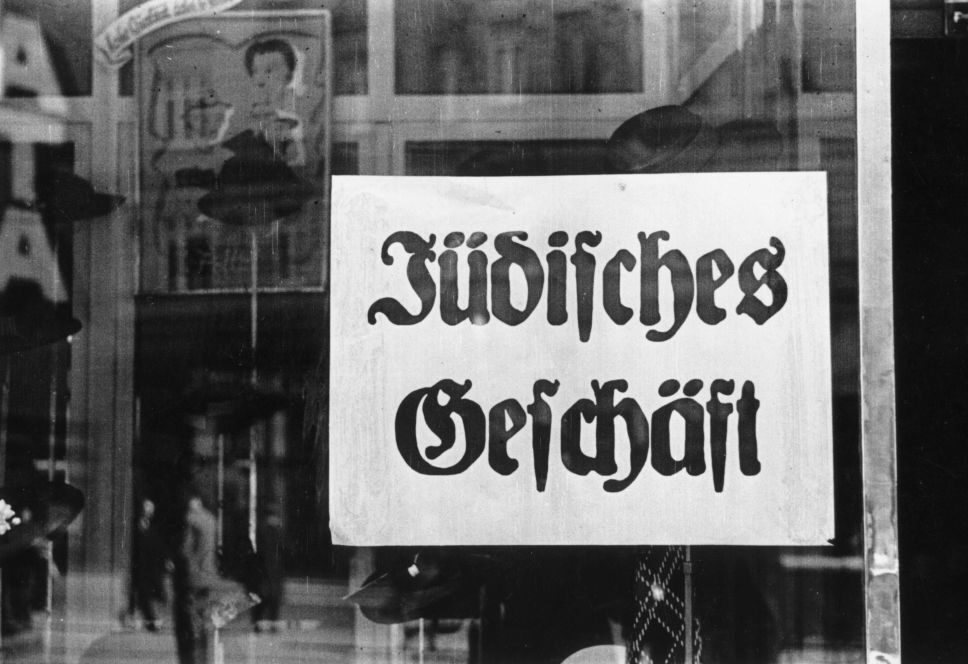

In Shakespeare’s text the war is a matter of strategic indifference to France, so that the king happily gives his vassals leave to fight on either side, but in Wentworth’s production it’s given the more somber trappings of World War I (though, perhaps in an echo of the text’s indifference, British, French, and Teutonic stylings seem to intermingle freely). The plot of the play, though, centers not on martial prowess but on two bits of trickery. On the battlefield, Parolles is goaded into undertaking the recovery of a lost drum, is “captured” by his own fellows who masquerade as enemy troops, and, via his easy willingness to betray all his own side’s intelligence as well as to disparage his compatriots to his captors, is exposed for the braggart and coward he truly is. Meanwhile, in the city, Bertram insistently woos a local girl, Diana (Allison Edwards-Crewe) which provides Helen with the opportunity to win her husband back with a bed trick. Diana will propose a rendezvous in the dark, first getting Bertram’s ring in promise, and Helen will substitute at the assignation, and thereby get herself pregnant. Thus Helen will fulfill the two conditions of Bertram’s letter.

It is, quite obviously, a mad plan even if one imagines it could come off, a doubling-down on the failed make-a-wish strategy that she used in curing the king. If Bertram were horrified to be Helen’s husband, how much more horrified would surely he be to learn she has tricked him into her bed? Bertram meanwhile presents a thoroughly repellent face when, returning to France upon hearing false reports of Helen’s death, the stories of his escapades in Italy come out, and he responds by viciously slandering Diana and perjuring himself. By the end of this, we wonder why Helen would want him; and we certainly can’t imagine that her trick could work.

But it does. Its only hope of working, I think, is for Bertram’s emotional reaction to mirror Parolles’s when he is caught out: “Who cannot be crushed with a plot?” That sounds like an excuse, which it is, but Parolles greets his unmasking with relief, an opportunity to finally be himself, and nothing more. That, I think, has to be what Bertram feels, less love for Helen (though surely he must wonder as much as she does at how “kind” she was in their moment in the dark) than gratitude that he can stop lying, and willingness in its wake to look at the world, and his wife, anew.

Wentworth stages the entire play as if it were one of Shakespeare’s late romances, and the recognition scene that ends the play specifically, when Helen, who all think is dead, emerges and weeps as she encounters Bertram, reads like the end of Cymbeline or even The Winter’s Tale. But this is not really a reconciliation because Bertram and Helen were never in love before. This is, rather, their first moment of recognition, of seeing each other in full as they are: a trickster and a cad, but also, they both know, a couple whose desire is fully mutual, even if, until now, their understanding was not. And from desire, there is the possibility, at least, of love, and of ending well.

That journey is an especially important one, I think, for audiences today who have been taught to focus on the formalities of consent over the deeper necessity of achieving mutual vulnerability. The proper role of wish fulfillment in dreams and folk tales is not to give you your heart’s desire, but to show it to you, and thereby open a path to that vulnerability that is a predicate to love. That’s what Helen’s bed trick accomplishes in the dream world of the play. All’s Well is a high-wire act from start to finish, but this cast makes it across. In so doing, they bring the old folk tales on which it is based to full and modern life again, as surely and as miraculously as Helen revived the king of France.

Noah Millman is theater and film critic for Modern Age.