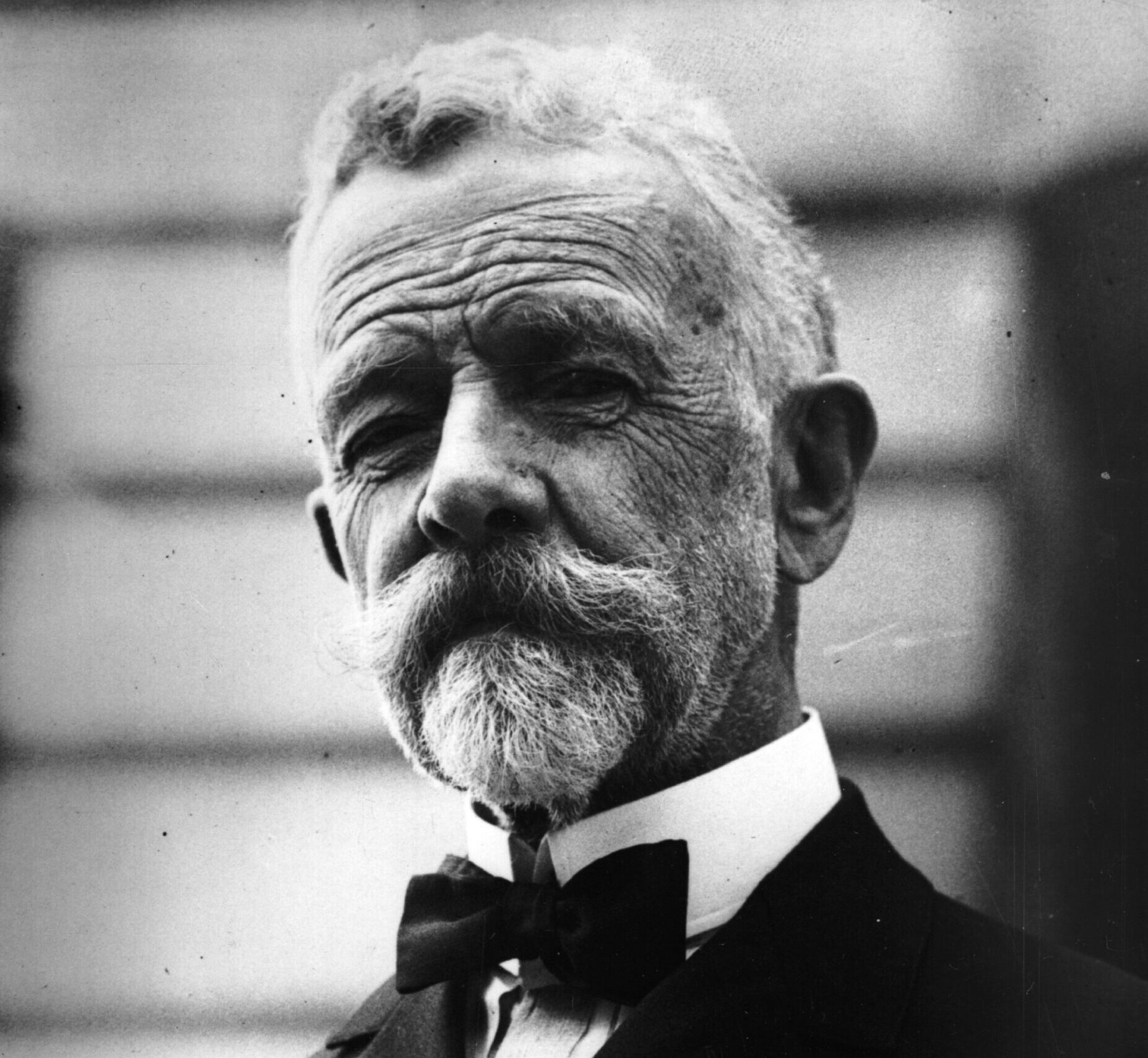

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Sr. (1850–1924) is best known for organizing congressional opposition to the Treaty of Versailles shortly after World War I. His leading role in that debate came at the culmination of a career in the Republican Party spanning more than 30 years. But before Lodge ever spoke of an interest in running for office, his calling was that of an historian.

One of the first Americans to receive a Ph.D. in history, Lodge grew up in a prominent Boston Brahmin family whose fortunes were made in maritime shipping. Under the supervision of Henry Adams, he wrote his dissertation at Harvard on Anglo-Saxon land laws. After receiving a doctorate in 1876, Lodge quickly turned to the study of early American history. A prolific and well-reviewed author, he published a great many books and articles over the next few years including biographies of George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Daniel Webster, and Lodge’s own great-grandfather George Cabot, also U.S. senator from Massachusetts.

Through his research and writing, the young Lodge developed a distinct interpretation of American history with practical consequences for his own day. The interpretation was one Lodge called Hamiltonian. And this Hamiltonian perspective would inform Lodge’s entry into political life over the course of the 1880s.

Lodge approached the study and writing of American history with a purpose. His goals were vindicatory, specific, and instructive. He worried that in Gilded Age America deep ethnic, class, religious, and sectional differences, the loss of historical memory, and a growing obsession with money had combined to loosen and erode the patriotic understanding of earlier generations. He looked to recover an awareness of U.S. history for his readers—that is to say, for U.S. citizens—in order to remind them of their common national past, their common national traditions, and their potentially common national purpose. For Lodge, the reading and writing of American history was itself a nationalist project.

The young Brahmin was skeptical of general or universal theories of history. Yet Lodge had a very strong sense of historical continuity in human affairs: “that however conditions change, the great underlying qualities which make and save men and nations do not alter.” Throughout his life, he found the study of history to be a source of political wisdom—perhaps the one true source. History was philosophy instructing by example. In fact it was a substitute for philosophical abstraction. He sought to learn from it and to apply its lessons to the present.

Lodge’s approach to the subject was also distinctly American. That is, he looked to inspire his fellow citizens with a deeper sympathy for their own country’s past. He aimed for a popular audience: “a scientific history, crammed with facts, well arranged, but unreadable … [is] as sad a monument of misspent labor as human vanity can show.” In keeping with his love of the theater, he believed useful lessons were best taught through vivid, dramatic, and personal examples. As he said, “the history of man is in large measure governed by … passion, sentiment, and emotion, and cannot be gauged, or understood, without the sympathy and the perception which only imagination and the dramatic instinct can give.” If American democracy faced immense challenges in his own time—and it did—then his inclination was to “look into the past, and see whether we cannot find suggestions that will help us in our difficulties.” This was a deeply conservative project. Lodge believed that certain worthwhile values and institutions from the past were under severe threat in his own time. He looked to preserve them. As his mentor Henry Adams said, Lodge “betrayed the consciousness that he and his people had a past, if they dared but avow it.”

The project of outlining a common national past, while admitting and recommending some elements of that past over others, required recognizing and celebrating distinct American subcultures and traditions within a national context. For Lodge, those subcultures worth celebrating could never really be doubted. They ran from the Puritans, to George Washington and the heroes of the American Founding, through Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists, to Daniel Webster and the Whigs, culminating in Abraham Lincoln, the Union, and the Republican Party during the Civil War.

Lodge admired the 17th century English Protestant settlers of Massachusetts not so much for their theology—about which he wrote little—as for their practical strengths, achievements, and “general principles.” The Puritans were notable for their ability to make political self-rule work at the local level, creating “conspicuous examples of successful popular government.” Largely isolated from their nominal masters in London, they had been strikingly independent. Lodge was struck by “their intense belief in themselves,” their “lingering faith … that they were a chosen people.”

He found the Puritans to be a source of “the ingrained conservativism and the reverence for law and order which New England always cherished,” a people “fit for leadership and command.” He respected their existential struggles against Native American tribes during King Philip’s War. As Lodge wrote, “the English Puritan was essentially a fighting man, and excelled in the art of war.” Indeed he worried that in modern times those older qualities were being “refined and cultivated to nothingness.”

The Puritans held to a grim view of human nature, alongside a continued belief in personal, political, and spiritual reformation. They did not believe in any secular “law of progress.” But they “faced the world as they found it and did their best.” Finally, Lodge admired the Puritans for what he called their “community of class”—their avoidance of great extremes of either wealth or poverty. He felt that only the Puritan example could rescue America from the rule of oligarchy, the “danger that the growth of wealth here may end by producing a class grounded on mere money, and thence class feeling, a thing noxious, deadly, and utterly wrong in this country.”

While completing his graduate studies, Lodge revealed a certain skepticism regarding popular narrative histories of great events and great leaders:

The general public does not care to have such pretty stories as that of Pocahontas exploded in a popular work, prefers to have the Revolution given in great detail because it is the only picturesque period, and are gratified by eulogistic sketches of the fathers, who are represented as striving together harmoniously against an indefinite evil character (not named) in order to found a nation.

That could have been Henry Adams talking. But as Lodge matured, he developed his own perspective on the Revolutionary era, coming to the conclusion that while the Founders were far from harmonious they did indeed build a nation and deserved a kind of eulogy. Lodge was proud of the key role that Boston played in the American Revolution. He was happy to concede, however, that the one indispensable man in its success was Virginia planter George Washington. Washington, for Lodge, was proof that an individual leader could make a critical difference in world events. That Virginian viewed the new United States, a federal constitutional republic, as “the last great experiment for promoting human happiness by a reasonable compact in human society.”

An effective battlefield commander and a compelling civilian leader, Washington understood the power of moral sentiment in politics and how to harness it constructively. To Lodge’s mind, “Washington’s work in lifting the country up from ‘Colonialism’ to Americanism and Nationality was one of the greatest things he did … the most useful sermon to be preached at the present day is one which would proceed from his example as a text.” Lodge found Washington’s most impressive quality to be his moral strength of character. In the end, national greatness was to be found in this strength and not in material things.

Washington’s approach to U.S. foreign relations provided a similarly useful model, “firmly founded upon a profound knowledge of human nature,” something that never changed. There was nothing “lingering” about him. He was “wise, dignified, and calm.” And once convinced of the need for action, he acted quickly and decisively. In reiterating America’s independent status from Great Britain years after the Revolution’s conclusion, Washington “grasped instinctively the general truth that Englishmen are prone to mistake civility for servility, and become offensive, whereas if they are treated with indifference, rebuke, or even rudeness, they are apt to be respectful and polite.” His aim here was not rebuke for its own sake, but the establishment of an external sense of status and deterrence on behalf of America’s “infant empire.” As the country’s first president put it: “There is a rank due to the United States among nations, which will be withheld, if not absolutely lost, by a reputation of weakness.” And such a reputation could only lead to war, not to mention loss of dignity and self-respect.

“Washington was not a phrase-maker,” said Lodge. “When he declared the country to be neutral he meant that it really should be neutral and in that capacity should not only insist on every neutral right, but should all perform all neutral duties.” This meant maintaining a robust US Navy, along with a demonstrable willingness to use it. It was Washington’s firm belief that “if we desire peace … it must be known that we are at all times ready for war.”

Alexander Hamilton was Lodge’s next historical hero. As America’s first secretary of the Treasury, the Caribbean-born Hamilton worked energetically to nurture the economic sinews of U.S. power through the creation of national banks, the encouragement of manufacturing, and the federal assumption of debt. He embodied one specific tradition in U.S. politics committed to strong federal government within a constitutional framework, capable financial institutions, domestic order, an effective Navy, a broad American nationalism, and a realistic foreign policy with all the necessary great-power accouterments. Lodge believed this tradition to be of central relevance in his own day, and that it had been vindicated by the Union experience during the Civil War. Nor was he alone in this belief. While Hamilton’s reputation had reached a low ebb compared to Thomas Jefferson’s in the early 19th century, many Northerners came to a conclusion similar to Lodge’s in the wake of wartime efforts.

Lodge looked to revive popular awareness of and respect for the Hamiltonian tradition. And he succeeded. Through his publications, including a nine-volume edition of Hamilton’s works, Lodge was one of the pivotal figures to assist in the rehabilitation of the image of Hamilton, at least outside of the South. As Lodge put it, after the Civil War “the American people … awoke to a full realization of the greatness of the work in which they had been engaged and of the meaning and power of the nation they had built up.” And no one “profited by these changed conditions more than Hamilton.”

Lodge’s view of Hamilton was not entirely uncritical. He did not admire the man’s sometime tendency to fall back on irregular means when especially agitated. A leading example was Hamilton’s letter urging John Jay to tilt the vote of New York in the 1800 presidential election. Lodge condemned this as “a most melancholy example of the power and the danger of such sentiments which are wholly foreign to free constitutional systems.”

Hamilton’s preference for “strength and order” in government was another issue of controversy, one that would always trigger suspicion in American political culture. Still, strength and order were better than weakness and disorder, and Lodge worked from that basis. The key was to encourage healthy national sentiment. As Hamilton put it, “we are laboring hard to establish in this country principles more and more national and free from all foreign ingredients so that we may be neither Greeks nor Trojans, but truly Americans.”

Lodge did not dwell on Hamilton’s aristocratic sympathies, nor on any shared fears with his subject regarding America’s democratic future. There was little to be gained by doing so in a country long since thoroughly democratic. The young historian was fully aware that the Jeffersonian tradition retained a great hold over the American mind. But he noted that in many ways President Jefferson and his successors were forced to rule “in the manner and after the methods prescribed by Hamilton.” This was precisely the argument Henry Adams made, with deliberate irony, in his magisterial history of the Jefferson and Madison administrations.

Lodge did not imagine that Hamilton would ever be considered lovable: “his genius and achievements were not of the kind which appeal to the hearts and imagination of the people.” He was rational, consistent and logical, with “nothing vague or misty” about him. Still, for Lodge, that was exactly the appeal. If anything, his admiration for Hamilton and his conception of American government only grew over time. Many years after first writing on the subject, Lodge concluded that Hamilton “was the greatest constructive mind in all our history, and I should come pretty near saying, or in the history of modern statesmen in any country.”

In the end, Hamilton deserved to be remembered above all for “the masterly policies which have done so much to make the nation and guide her along the pathway to her mighty destiny.” Among the Founders, only George Washington had an equal grasp of “the imperial future which stretched before the United States.”

For Lodge, “the Federalists, from 1789 to 1801, were the ablest political party this country has ever seen.” In their own day, he thought, the Federalists were really the party of progress, championing a more effective, capable, and energetic Union on modern commercial lines. They were “a class of clear-headed, strong-willed, sensible men” who “never fell into the mistake of abandoning practice in favor of theory.” They were realists. They stared facts in the face. They were “the first American party.”

Descended from leading Federalists himself, Lodge looked to restore their reputation along with Hamilton’s. As with his biography of Hamilton, Lodge had a fair amount of success in doing so, and for the same reasons—namely, the lived experience of the Civil War and its consequences. Lodge was sometimes accused of being partial to the Federalists, but he never denied it: “I have not sought in treating New England Federalism to write a judicial and impartial history of the country; my object was to present one side and that the Federalist, in the strongest and clearest light.”

He was particularly sensitive to charges that the 1814-15 Hartford Convention amounted to proof of New England Federalist treason. That really cut to the core. His own great-grandfather, Senator George Cabot of Massachusetts, had presided over that convention. Lodge otherwise held up New England Federalists as a model. Treason or betrayal of one’s own country was about the most hateful crime that Henry Cabot Lodge could imagine. Lodge’s solution was to argue that the Federalist tradition, taken as a whole, deserved vindication, especially given the lessons of the American Civil War. The Federalists had considerable success in rendering the new American democratic model workable, building in safeguards against the tyranny of the majority and other dangers.

Still, they were unpopular, and in certain ways had been ever since Jefferson resoundingly defeated them in the election of 1800. As in his work on Hamilton, Lodge did not dwell on the Federalists’ aristocratic sympathies, nor on their deep misgivings regarding the future of democracy. Rather, he focused on their undeniable American nationalism. Possessing “a greater amount of ability than was ever displayed by all other political parties in America,” the Federalists were on balance a positive model for the present.

In foreign affairs, Lodge admired the Federalist willingness to maintain “a vigorous neutrality, ever on the alert and ready for war.” This was the only way to protect U.S. interests. Federalists recognized that international politics had its own logic, not always amenable to lonely assertions of equal justice or moral superiority. In reality, as Washington understood, nations were ranked by others according to their strength, leadership, material capabilities, and reputation. To deny this was dangerous, delusional, and irrational, making war more likely and successful diplomatic accommodations less so.

Lodge could not deny that prominent Federalists, including Hamilton, possessed a favorable view of Great Britain in its struggles with Revolutionary France. Instead, he portrayed that favorability as a counterweight to Jefferson’s predilections for the French Revolution, while condemning all such foreign leanings as “a curse upon our politics.” Federalists did not think the U.S. could unilaterally disarm in a world characterized by competing great powers. They maintained “a bold and strong neutrality … ready to strike at the first nation, no matter which it was, that dared infringe it.”

Lodge believed that approach had been vindicated by the Quasi-War with France, wherein Admiral Thomas Truxtun and other U.S. naval commanders fought undeclared naval hostilities with French ships in the Caribbean and beyond. But Lodge worried that Hamilton’s Federalists had not convinced the voters, or even President John Adams, of their foreign policy approach:

They had initiated the policy of strong and real neutrality, protected by an efficient navy; but they had not habituated the people to it, nor had the glories of Truxtun’s victories been sufficient to make men realize that the sea was the field on which our power could be best maintained and asserted. The foreign policy and the navy were, therefore, the two points on which Jefferson’s attacks could and did succeed.

Lodge admitted that Jefferson was “a great man no doubt,” and in strictly political terms a successful party leader. But he was also a “sentimentalist of muddy morals,” supple, crafty, and inconsistent. Like a French doctrinaire, America’s third president often sacrificed practice to theory, a tendency that made effective statecraft impossible. His most striking characteristic was the yawning gap between his beautiful public statements and his day-to-day actions, whether with regard to foreign policy or the potential freedom of his own slaves.

Jefferson, according to Lodge, placed too much faith in universal abstractions, rather than recognizing the stubborn differences between particular national cultures. The United States’ example of stable republicanism would not necessarily spread to unstable France, and the French Revolution was certainly no model for Americans. Jefferson “was utterly at fault in supposing that there were in the United States the same elements and the same forces in France … history made their existence impossible.”

Lodge shared Gouverneur Morris’s view of Jefferson. In Lodge’s words, Jefferson “believes, for instance, in the perfectibility of man, the wisdom of mobs, and the moderation of Jacobins. He believes in payment of debts by the diminution of revenue, in defense of territory by reduction of armies, and in vindication of rights by the appointment of ambassadors.

Foreign policy was, for Lodge, Jefferson’s single greatest weakness. Lodge was well aware of the continuing hold of classically liberal and Jeffersonian ideas on American political culture in foreign affairs. Americans desired peace, and like Jefferson, they were often inclined to believe it could be achieved through economic means rather than military preparedness. But “Jefferson and Madison were hesitating and timid. They swallowed insults in the name of peace and landed us in war.”

Jefferson’s classically liberal belief in the legal equality of nations was not a reliable guide to the actual workings of international power politics. He seemed to have little conception of what motivated Europe’s great powers to act—that is, broader national interests including security, prestige, and relative wealth that they themselves would define. In place of the Federalist foreign-policy model “was substituted a timid, exasperating policy of peace protected by commercial warfare.” Henry Adams agreed, viewing Jefferson and his presidential successor James Madison as incapable of delivering a workable foreign policy. Jefferson especially acted “as though eternal peace were at hand,” Adams wrote, “in a world torn by wars and convulsions and drowned in blood.”

The Civil War era, for Lodge, was the ultimate test of the national experiment, equaled only by the American Founding. It also provided lasting examples of effective statecraft, as well as contrary dangers. Under his father’s healthy influence, Lodge reached the conclusion as a boy that the enslavement of African-Americans was not only wrong but a threat to the continuation of the experiment in constitutional self-government. Yet in those fateful years leading up to the war, there was more than way to tackle that injustice. Precisely in order to build support for what had to come, a course both principled and pragmatic was required. And in this regard, as later, Abraham Lincoln showed the way. As a boy growing up in Boston, Lodge revered Lincoln. Decades later as a man, following much experience, reading, and reflection, the aging senator saw little reason to reverse that estimation: “With some habit of weighing and judging men historically, I have come to the conclusion that Lincoln was the greatest man of his time … No one else moves in his orbit.”

Lincoln’s wartime leadership provided an exemplary lesson in how a nation could be moved and preserved. Like Daniel Webster, a great influence on his thinking, Lincoln understood the power of American national sentiment, along with the overriding need to save the Union. Unlike Webster, Lincoln understood that ultimately the movement against slavery neither could be nor should be denied. Lincoln realized that in the United States, civic progress and civic nationalism went hand in hand. Lodge noted early on:

Lincoln was the true conservative, and he gave his life to preserve and construct, not to change and destroy. The men who sought to rend the Union asunder in order to shelter slavery behind states’ rights, the reactionaries who set themselves against human liberty, were the real revolutionists. Lincoln’s policy was to secure progress and right by the limitation and extinction of slavery, but his mission was to preserve and extend the Union. He sought to save and to create, not to destroy; and yet he wrought at the same time the greatest reform ever accomplished in the history of the nation. Let us learn from him that reaction is not conservatism, and that violent change and the abandonment of the traditions and the principles which have made us great is not progress, but revolution and confusion.

The Civil War also educated Lodge in basic realities of world politics. Even as a boy, he was appalled to hear of any British and French ambiguity toward or sympathy for Confederate rebels. As the United States fought bloodily for its very existence, Lodge noted, leading figures in Paris and London offered words of praise, or even material support, to Southern secessionists, while taking advantage of America’s life-and-death struggle to advance their own ambitions south of the Rio Grande. Nations, it seemed, consulted their own particular interests. It was a lesson Lodge would never forget.

In his own day, Lodge feared that “the insidious gentleness of peace and prosperity had relaxed … the practice of some of the virtues called out by war.” The war revealed that democracy could not preserve itself without the revival of certain ancient characteristics. These included the heroic virtues demonstrated by countless Union soldiers and officers such as Robert Gould Shaw and his men. It was the character of its people, their patriotism, and the effective channeling of that national sentiment into instruments of military power—not simply universalistic abstractions—that ensured the survival of the Union. Lincoln recognized, explicitly, that it was on the progress of American arms that all else depended. Hamilton would have understood. Still, the war’s outcome convinced Lodge that there existed a kind of grounded, nationalist majority who would respond to “a leader who seems to consult … the interest and dignity of the country.” He was left with a lifelong impression that the American public would ultimately master any challenge.

Sustained reflection on U.S. history, dating back to the Founding, led Lodge to conclude there was more than one political subculture or party tendency within that history. As he put it, there is “a great persistence of inherited traits in political parties as well as in men.” The one he most admired was the Hamiltonian. From the very start, Lodge decided, there had always been one party—whatever its name—dedicated to a robust federal union, human liberty, balanced progress, constructive legislation, internal improvements, constitutionalism, and the protection of U.S. national interests at home and abroad. From the 1790s into the very early 19th century, that party had been Hamilton and the Federalists. During the 1830s and 1840s, it had been Daniel Webster and the Whigs. And since the 1850s, that role had been assumed by Lincoln and the Republicans. In the end it was really one continuous political tendency: “the party which at different times has borne these three names has been … in its essential characteristics and qualities, the same party.”

Indeed, his own family had always worked within that tradition, “brought up in the doctrines and beliefs of the great Federalist, the great Whig, and the great Republican.” It was a tradition both practical and idealistic in the true sense. Gilded Age Democrats, by contrast, seemed to be an unhelpful combination of neo-Confederate segregationists, arch-reactionaries, populist radicals, impractical intellectuals, and corrupt big-city machines. Lodge looked to resuscitate popular historical awareness of the Federalist-Whig-Republican tradition at its best and vindicate it in his own time. This was both descriptive and prescriptive. To advance a new Hamiltonian agenda, Republicans needed to be reminded of who they were, and where they came from. As he said: “The policy of the Republican Party is a national and American one, and as I would have been a Federalist or a Whig, so I am now a Republican, because I find running through all the history of the party the thread of protection to national and American interests.”

Lodge’s theory of a single distinguished American political tradition stretching from Hamilton and the Federalists, through the Whigs, to Lincoln and the Republicans, did not let the Gilded Age GOP off the hook. Far from it. He had high expectations for his hereditary party and was disappointed when it did not live up to them. That too was a major motivation to enter the arena. The pathway forward was undeniably treacherous and uncertain. Through an act of will, he determined to take part in the struggles and events of his own day. He did so because he saw cherished values being challenged. He aimed to salvage and preserve as much of that world as he could. At the same time, he was practical and intelligent enough to understand that one could not truly turn back the clock except in memory and imagination. So he recognized the need to make certain carefully considered accommodations with existing real-world changes. The goal was some sort of healthy reintegration of society, at both the local and national level.

Reflection on the Civil War and on the Hamiltonian tradition convinced Lodge that the laissez-faire political culture of the antebellum era only had so much use. In the end, the Union had been saved through a massive, practical, collective effort channeled through government institutions. In turning from history to politics, Lodge would look to vindicate himself, his family, his city, and his country. Both the historical profession, and the political one, were a means of pushing back against contemporary trends and conserving as much as possible of what was worth conserving from the past.

Colin Dueck is a professor in the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University and a nonresident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. His most recent book is Age of Iron: On Conservative Nationalism.