After almost twenty years America’s invasion of Afghanistan ended in a startling defeat, with the deaths of American boys too young to have seen 9/11 but whom our politicians and generals nevertheless turned from soldiers into very easy targets for suicide bombers. An anonymous bureaucrat at the Pentagon then ordered a drone strike which killed some even younger Afghans: children. The generals and politicians pretended for a while that these further human sacrifices were dangerous terrorists, only to acknowledge later that mistakes had been made.

Every president starting with the younger Bush has talked about our wars since 2001 in terms of human rights, over time especially the rights of women and girls. American elites followed their lead, caused vast destruction in places like Afghanistan, sent in soldiers to die by the thousands and kill tens of thousands, while making hundreds of thousands of Afghans homeless refugees. This terrible strife in that mountain desert country came to rival the Soviet intervention a generation back, except that American elites pretend the chaos they have sown is really Enlightenment, an education in pacifism, liberalism, and feminism. The Soviets were primitive, so they killed people in Afghanistan to conquer and enslave the country—they lacked Ivy League education; American elites instead only invade foreign lands for their own good.

This, then, is the double paradox we need to understand if we are to change the mad liberalism that now rules in America. First, the greatest technological power the world has ever seen was defeated by religious fanatics whom we suspect of being not only illiterate but proud of it, too. “Godless Harvard loses to the Muslim Taliban in the Year of our Lord 2021” is quite a headline. In Ashraf Ghani, our elites even gave Afghanistan a TED Talk-delivering, Ivy League Ph.D., former World Bank official for a president, a technocrat who specialized in saving failed states. So how has Afghanistan failed to become a liberal campus-cum-NGO? Second, the most highly educated elites in world history, out of pious cruelty, created hecatombs that would have made the Romans and the Aztecs proud. Again, not a headline we are used to: “Humanitarian elites perpetrate what humanitarian elites call crimes against humanity.” And thus not a headline you have ever seen. Faced with our paradoxes, we look away.

Now that it is all over, we should be manly enough to see what our liberal elites did in America’s name and with American blood and treasure, and to understand why it was possible, even easy, to drag the nation into this protracted evil. Elites no longer have the power to silence discussion or use their contempt to make disagreement seem worthless. It’s possible to learn what we should have learned long ago.

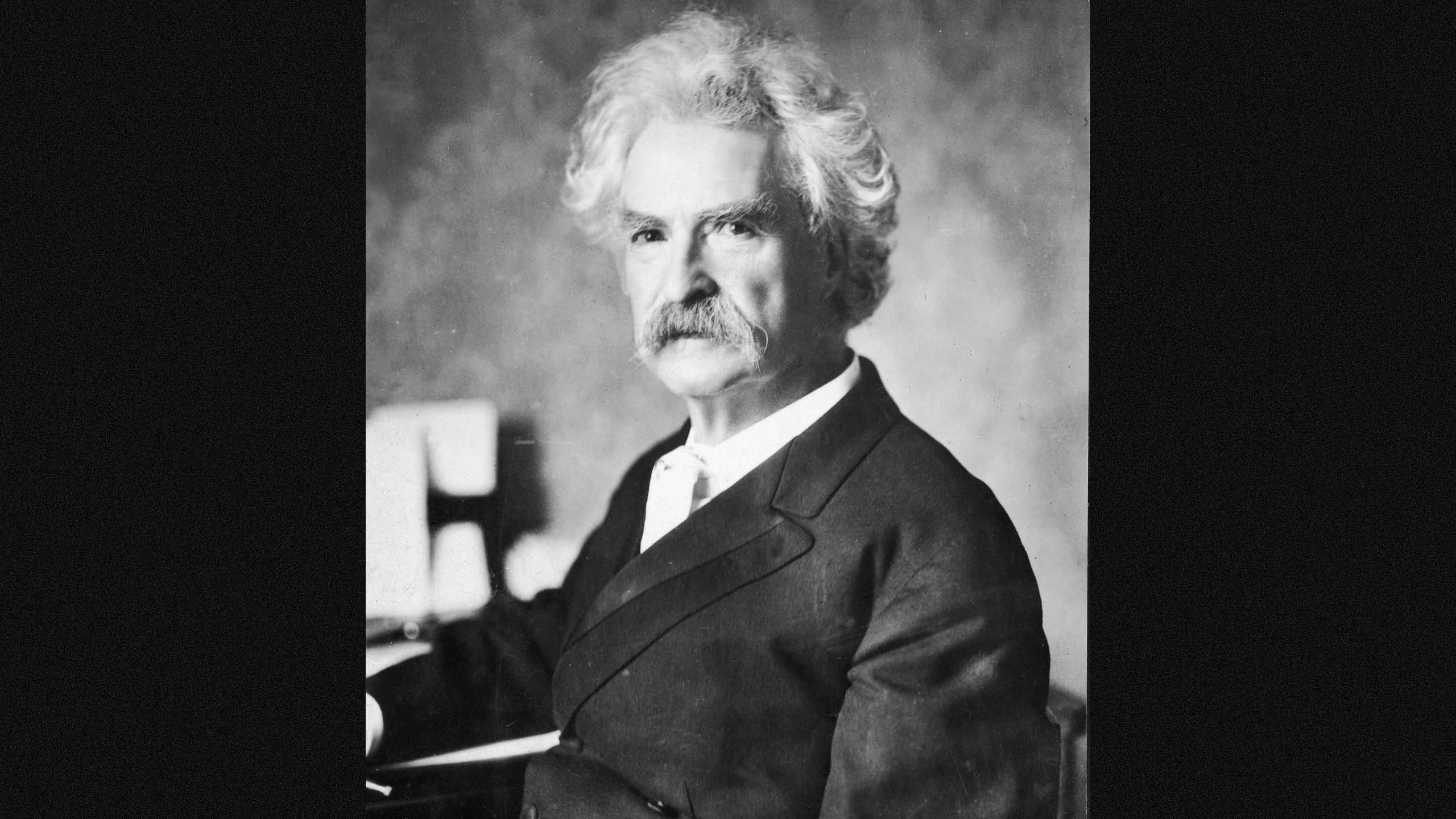

Mark Twain’s America

The story of a mediocre but ambitious Yankee who encounters religious fanatics that believe in honor and slavery, and who then tyrannizes them for their own good—bringing Enlightenment to the Dark Ages, only to turn the children of the benighted turn into technological murderers of their own people—is one of the old American stories. Mark Twain published it in 1889 and called it A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. It may seem shocking that the invasion of Afghanistan was foretold—swapping in Islam for medieval Christianity—but it shouldn’t. The belief that the 21st century will win against the 7th is only a modification of the longstanding belief that modernity is superior to antiquity, that we today are the self-fulfillment of history, our every action evidence both of Progress and the reward of Progress.

Twain believed, as we all do, that democracy is more just than aristocracy, that freedom is better than slavery, and that the people who romanticize or idealize the past are usually mad and cannot be trusted. He mocked the ignorance, arrogance, and cruelty of the knights of the Round Table because he thought all this talk of chivalry had much too much attraction for Americans in his time, as in ours. But Twain was a comic writer, and so Americans laughed at him! Worse, since he was not writing sentimental tragedies about Arthur and Camelot, American democracy turned to other poets for an education, and fantasy won a decisive victory over good sense. Even today, American kids learn their morality from silly fantasies, only to grow up to damn Twain as racist. This is merely a disguise for the real reason—Twain knew what was wrong with American ambitions, and he told the story in a remarkably persuasive way, a crime for which he cannot be forgiven.

Twain believed, moreover, that Americans should look to their own lives rather than to foreign ideas, that they should respect American writers like himself instead of European writers, and that the future of democracy depended on American confidence. He admitted that America lacked European splendor, but he pointed out that Europeans were constantly at each other’s throats like beasts. He preferred American mediocrity to those extremes of beauty and madness, but he feared that his reasonable patriotism was of no interest to his fellow Americans. American elites were slavishly imitative of British aristocracy in his day, and they are still slavishly imitative today of what is called globalization: not because the elites are so different from ordinary Americans but because they are the same, and they hate that sameness. Worse still, Twain feared that ordinary Americans secretly share this self-hatred, despite pieties about the land of the free and the home of the brave, the flag, anthem, and the 4th of July, or that audacious Novus Ordo Seclorum.

Americans are funny because they know themselves to be democrats, but they are every day trying to escape that condition by acquiring fame. It’s part of American greatness that Samuel Clemens could become Mark Twain, but it comes with the terrible downside that endless numbers of mediocrities can afterward counterfeit the immortal glory that Twain earned. Worse, Americans are always tempted to mix hostility and indifference and to persecute comedy altogether. This is because the more they feel democracy is their fate, or at least their birthright, the more they rebel against it, yet without giving it up. They believe in equality, but fear it makes their lives useless, objects of mockery rather than praise. This makes Americans competitive about everything, always looking for something to brag about, in the hope that their equals will pay attention. It’s a land of envy where only the man who punctures egos is a public enemy, but every flatterer is considered a friend and teacher: this is the power of positive thinking. Usually, criticism of American materialism revolves around money—in America, kids can make untold billions and act like demigods; indeed, in America you can believe that God wants you to be rich!

To Twain, American success is very funny for this reason, that it is built on self-loathing and trickery, but he doesn’t think it’s a joke—love of money doesn’t blind him to the real problem caused by the power that comes with commerce, industry, and technology. Twain feared Americans would never really love him because they love technology too much, which they hope will cure democratic restlessness, which is a fear that life is passing us by, and that this same fear afflicts everyone else, to such an extent that it prevents them from paying attention to the important things in life—ourselves.

Why We Fight

Comedy is a little like philosophy in that it prefers ugly truths to beautiful illusions. Twain’s mockery of American elites might remind you of Socrates, as might his skepticism about democratic attachment to decency and justice. Comedy might indeed be what democracy desperately needs. The first comic was the poet Aristophanes, and he sang of Athens, as imperial a democracy as America, as cruel to peoples in distant lands whom it considered inferior, as shameless in proclaiming its rational superiority when it perpetrated terrible injustice.

Twain accordingly turns to an ancient story in his Yankee book: He takes up the political biography genre that stretches back from Plutarch to Xenophon to Sophocles and Homer. He gives us the story of a mythical founder, Hank Morgan, Sir Boss, who seems wise beyond the powers of ordinary humanity and whose astonishing achievement nevertheless disturbs us, whether by its ephemeral character or its fearful consequences. Twain takes the self-made man, the most popular character in America, and turns him into a tragic hero. He takes his vengeance on the democratic weakness for moralistic heroes, you could say, by telling a story every American can fall in love with, only for him to terrify them at the end. In America, everyone is scared of failure, a consequence of our freedom, but Twain wished to teach his audience to fear success because otherwise they would sell their freedom to whoever seems successful.

Twain’s protagonist, Hank Morgan, tells his own story:

I am an American… I am a Yankee of the Yankees—and practical; yes, and nearly barren of sentiment, I suppose—or poetry, in other words. My father was a blacksmith, my uncle was a horse doctor, and I was both… Then I went over to the great arms factory and learned my real trade… learned to make everything: guns, revolvers, cannon, boilers, engines, all sorts of labor-saving machinery. Why, I could make anything a body wanted—anything in the world, it didn’t make any difference what; and if there wasn’t any quick new-fangled way to make a thing, I could invent one—and do it as easy as rolling off a log. I became head superintendent; had a couple of thousand men under me.

He is given to boasting, apparently, or at any rate is proud of his powers, which come from knowledge and give him a title to rule other men, who know less. This creates, of course, a political problem:

Well, a man like that is a man that is full of fight—that goes without saying. With a couple of thousand rough men under one, one has plenty of that sort of amusement. I had, anyway. At last I met my match, and I got my dose. It was during a misunderstanding conducted with crowbars with a fellow we used to call Hercules. He laid me out with a crusher alongside the head that made everything crack, and seemed to spring every joint in my skull and made it overlap its neighbor.

Both his job and his attitude are tied up with violence, but Hank is blind to this, perhaps because he thinks his violence is good, or it would be if it were successful. The problem is that everyone he deals with is as American as he is, so they don’t want to be bossed around. As a democrat, Hank has recourse to a fair fight, but he loses to a man called Hercules. Hank really is an intellectual—an ordinary man would have taken the hint included in that reputed name and avoided the fight, whereas Hank apparently is out to prove to his men that, being smarter, he’s destined to win.

So it is no accident that this man of the industrial age, in which science is power, is knocked all the way back to the year 528, when the political title to rule was the most unintelligent one imaginable, strength. Hank, who tells his own story, entirely lacks self-knowledge, so he doesn’t make the connection. The lesson he learns by being faced with Camelot is that he could take over England with the greatest of ease. His desire to rule men without their consent, a tyranny not so alien to democracy, is only heightened because the medieval people he encounters are not democrats. This proves they’re both immoral and unintelligent, which apparently does nothing to make them less attractive to Hank as subjects. But this is concealed from us because we like underdogs, and Hank in the land of knights is immediately captured as a slave, a victim of the acquisitive cruelty that humiliates us, since we suspect we might be as cowardly as Hank in face of danger. In fact, we want him to succeed—enlightening the medieval population that laughs at him in the early chapters of the story is the sweet revenge we desire. He compares the aristocratic order to a circus, but he is also a freak to them, and this mutual contempt must lead to war.

Hank Morgan becomes Sir Boss because he is the champion of a cause—our cause, which is either democracy or science, the two being easily confused since they share the same enemy, the unenlightened aristocracy of the past. Being irrational, the politics of the past must be conquered by the new science, which is above all rational in ignoring what human beings say about their merits, motives, and duties.

American power

This might remind you of repeated American attempts to civilize foreigners who are historically backward, attempts that started not long after Twain published this story. America is newer than other nations, its government is more rational or scientific, and it has accordingly a conspicuous lack of self-knowledge. History is what happens to other people. American elites only take to an extreme what is often true of Americans: they are theoreticians, which is why they find it easy to believe the world could be America. Another way of putting that is: they’re not particularly tied to any place, or habit, or belief.

We are compelled to give this very skeptical view of American power because of our circumstances: America after the Cold War was more powerful than any political community had ever been in history, but the result has been that in one short generation we have come to hate each other, lose our confidence, and inflict catastrophes on various parts of the world. Our success has given us not the elites that we needed to use it well but instead people in their ignorance and arrogance are far worse than the medieval knights Twain wrote about.

Twain is not anti-American, of course, but he wishes to give an account of American power that tells the truth about human nature. Rationality favors democracy to the extent that it recognizes our common nature, our ability to think and speak about our concerns, and our need for each other if we are to survive in an insufficiently provident world. But rationality is also the enemy of democracy since most people cannot be scientists, and even among scientists the difference between the great and the mediocre is astonishing. Our minds make us as powerful in this world as Hank Morgan is against the knights, but also as dangerous because our minds cannot erase the distinction between the scientist and other people.

Hank Morgan solves his problem by not thinking about it—that is, through enlightenment education. Hank first ascends from slave to King Arthur’s special adviser by confronting Merlin. Superstition is no match for science, it would seem, at least among people so superstitious that they confuse Hank’s prediction of an eclipse with his production of the same. This original ambiguity about his achievements will eventually doom him.

The next step in building the Americanized elite is the transformation of a refund based on honor into one based on commerce, making the knights into something of a financial oligarchy. This brings up questions about the men’s loyalties, and the extent to which they could become satisfied with a life where risk is abstract, tied to speculation, not personal. The final step is a full regime change built on a secretive institutionalization of science through schools and factories. Only in this case does Hank even think about securing loyalty, creating powers that depend on him and his innovations. Yet this is also the most revealing part of his enterprise, based as it is on a conspiratorial new elite completely alien to England, Christianity, and the peasantry.

Hank delights in the power to change things and people. He is not only a founder but almost a god. This belief that every problem can be solved is as American as it gets. Yet Hank’s problem, and ours, is that beliefs turn out to be much harder to change—because we hold our beliefs in order to prevent change: in order to stay the same, that is, to be ourselves. Hank in modern America was enraged by American recalcitrance toward his rule. But in medieval England he not only proves too recalcitrant to change himself, he deludes himself that changing what people do also means changing what they believe.

Yet the moment Hank takes a vacation for his health, a civil war starts and England goes back to the old ways. Hank’s return is monstrous, he leads kids to slaughter an entire army of holy knights with modern weaponry until his own minions choke to death on the stench and diseases arising from the corpses. His modern revolution collapses as quickly as it had started, but with none of the comedy. At some point, his democratic criticism of morality turns into horror, though he is unable to detect the change; nor are we, given his showy successes and our contempt for the backward people on whom he experiments. It’s worth recalling his initial confidence: “I would boss the whole country inside of three months; for I judged I would have the start of the best-educated man in the kingdom by a matter of thirteen hundred years and upward. I’m not a man to waste time after my mind’s made up and there’s work on hand.”

Morality

One of Hank’s achievements seems less perishable than the others. He takes the king on an incognito tour of the kingdom to see how people really live their lives. This turns out to be imprudent, and they get in trouble, but the result is that King Arthur begins to abolish slavery after himself experiencing slavery and leading a slave revolt. This is not really Hank’s doing, but it’s the sort of reform he desires. Yet he never stops to think that America had to endure the most horrifying war to end slavery, and even that victory proved unable to strengthen democracy enough to extend it fully to black American.

So it is with American elites trying to transform ways of life more ancient than America itself: they believe it’s the easiest thing for their superior minds to redesign the lives of tens of millions of strangers. The self-evident character of our democratic morality makes it almost impossible to understand any other moral principle or practice. We react with indignation to moral opinions that contradict our own, but we’re never aware that others feel the same way about us. Our elites are not different, except to the extent that they also despise us. Worse still, their belief in their sophistication, which is nothing but the fame ordinary Americans give them, makes our elites incapable of learning from experience. So too Hank among the medieval English is outraged at the wanton cruelty but unable to learn at any point that the common people are his enemies far more than the aristocrats are, because the people have, so to speak, nothing but their belief in their way of life and little interest in the methodical science that gives him power. Like American elites in Afghanistan, Hank thinks himself the truly democratic ruler, and therefore legitimate, even though everything he does is based on fraud and only the local elites are really in league with him.

In the end the catastrophe that engulfs Hank comes from religion, just as surely as in our misadventure in Afghanistan. Hank is as atheistic as our elites, as contemptuous of religion, as blind therefore to its powers. He sees only what he despises in the English, he has no respect for what they manage to accomplish in very harsh circumstances. But they know who they are far more than he does, not least since he has no loyalties. His fascination with the scientific power to change things, to be free because he is nothing but what he makes himself out to be, has a moral core: Hank wants to make people in his own image because it’s the only way to prove to himself that he is right, that he knows the truth, that his dissatisfaction with the world is justified. He seems selfless, an utterly public man, his every action a benefaction to others, concerned with himself only when he is attacked and just to defend himself. Thus do our elites see themselves. Yet this makes him tyrannic since he can never leave people alone. Ironically, he achieves his purpose: England becomes briefly as unknown to itself as he is to himself. He does not achieve self-knowledge but instead robs the country of its peace.

So we end with the paradoxes with which we began: how can elites be as humanitarian as they endlessly profess themselves to be and yet be hated everywhere, or at least not loved? How can superstitious primitives be so much wiser in their understanding of their enemies and of events? It seems technological liberalism is too immoderate to win, or even sustain itself, because its expectations are god-like. Nor does defeat teach them anything, since they believe morality makes them irresistible. If anything failure proves to them that they are right, in the sense that people who reject liberal Progress are obviously mad.

Let us not forget, however, that whereas Hank ended up losing everything in his foreign adventure, to the point that the medieval drama of Arthur’s court continues, leaving him behind, he started out very angry at his fellow Americans for their insubordination to his will. Our own elites have been defeated in Afghanistan, but this will only lead them to blame us and take out their anger on us. After the catastrophe abroad, the one at home. Twain tried to offer America an account of our techno-moralism, its utopian expectations and its obliviousness, its brutality when challenged and its ignorance of history, in order to help us control our elites, who very easily go mad in the attempt to justify their unique privileges on the basis of equality. They want revenge on us because they have to share their humanity with us. Twain warned us about tyranny, it’s time we learned from him.

Titus Techera is the executive director of the American Cinema Foundation.