In late 1949, writing in the final issue of Horizon, the periodical he founded and then edited for many years, Cyril Connolly famously described the dawn of the postmodern era with these words: “It is closing-time in the gardens of the West and from now on an artist will be judged only by the resonance of his solitude or the quality of his despair.”

Connolly believed that humanity had entered a new era, one aptly described by the conservative historian Russell Kirk (1918–1994) as a time when faith in ancient religion has been shaken and largely discarded; when old customs and forms of governance have disappeared; when profound economic changes have come into being to alter our modes of livelihood; when the expectation of private and public change has become greater than the expectation of private and public continuity; when the family seems everywhere imperiled; and when men can no longer live as their fathers lived before them, but instead wander bewildered in new ways.

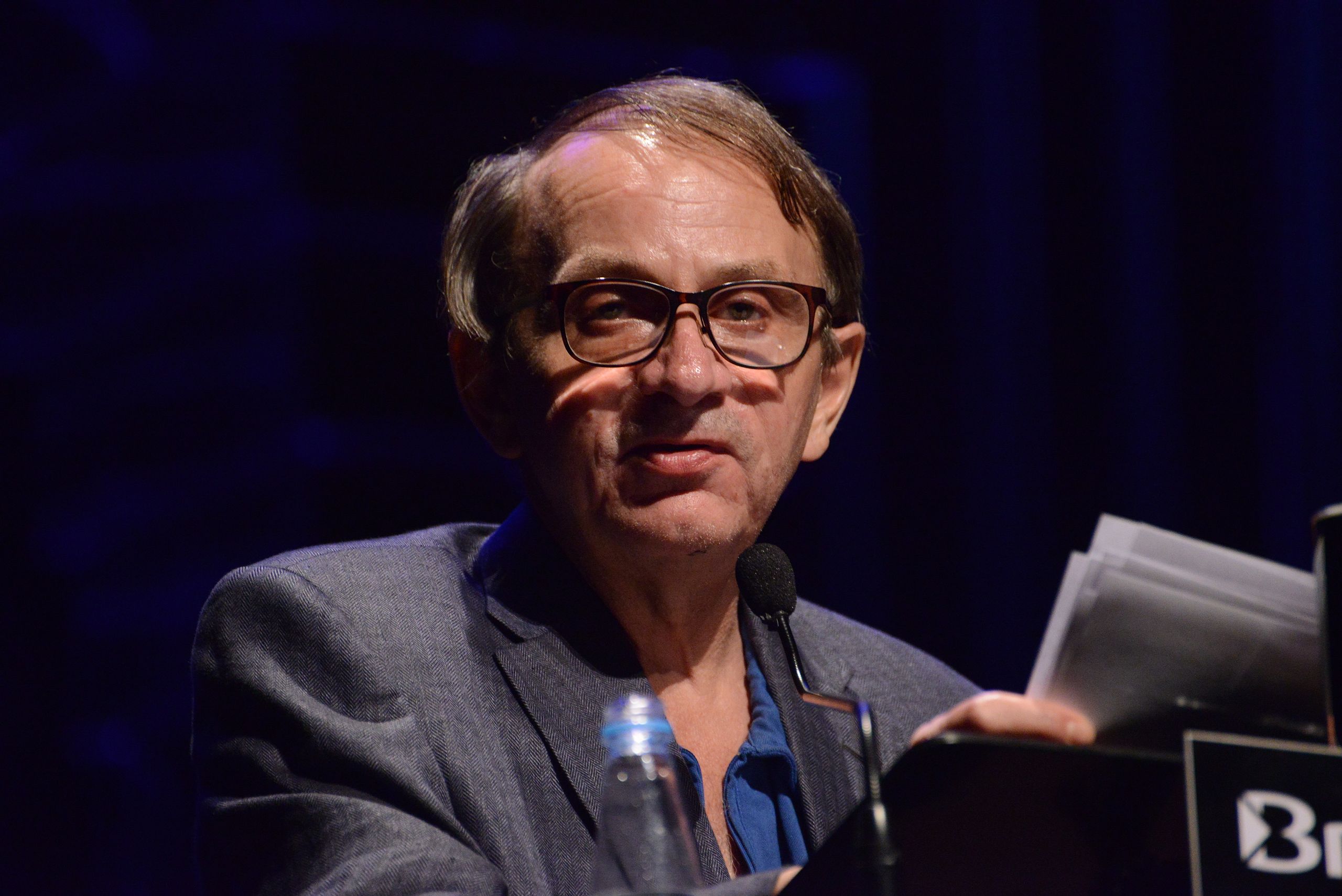

Unsurprisingly, the works of our hands reflect all these developments, especially in architecture and literature. Within the body of imaginative literature that describes the bewildered wandering of many moderns, perhaps the novels of French author Michel Houellebecq (rhymes with well-beck, 1956– ) most effectively serve to illustrate this point, describing a world in which the spiritual aspect of humanity—that aspect that provides aim and purpose to life—has effectively vanished throughout much of the West. In such novels as Extension du domaine de la lutte (1994, translated as Whatever), Les Particules élémentaires (1998, The Elementary Particles), Plateforme (2001, Platform), and La Possibilité d’une île (2005, The Possibility of an Island), Houellebecq depicts men and women who simply exist day after day in aimlessness, boredom, and ennui, their lives highlighted by vigorous but ultimately noncommittal sexual encounters. Otherwise, these characters fill their time counting the minutes until the days of their earthly lives are utterly spent.

Mankind can abide nearly anything except boredom. During the long wait for death, Houellebecq’s characters sense that the essence of their world is empty, and they long with little hope for something—anything—to be revealed to give their lives a sense of meaning. They intuit that love has something to do with life’s purpose, but that eros is fleeting and does not suffice, with the effects of aging damping down the energy of mind and body. They long forlornly for the possibility of an island—a patch of solid ground to stand upon within a sea of purposelessness. But they are forever pulled back by the Mephistophelean offerings of the world and the flesh, which do not satisfy. Houellebecq’s novel Platform describes the world of sex tourism, in which bored Westerners take vacations to the poorer countries of East Asia to indulge in high-end sexual adventurism. Having experienced this tawdry world to the full, the central character admits its emptiness and his longing for something better: “I wasn’t happy, but I valued happiness and continued to aspire to it.” Elsewhere in the novel, the same character declares: “To the end, I will remain a child of Europe, of worry and of shame. I have no message of hope to deliver. For the West, I do not feel hatred. At most I feel a great contempt. I know only that every single one of us reeks of selfishness, masochism and death.”

Like John Webster, Houellebecq is much possessed by death and sees the skull beneath the skin—and not just the dissolution of men but the dissolution of Western culture amid what he calls, in The Possibility of an Island, the “authentic horror of the unending calvary that is man’s existence.” Given this standpoint, it may be surprising to learn that critics have commended the comedy to be found within Houellebecq’s works; but it is a rictus comedy, not the chuckle-aloud variety. Rollicking is not an adjective readily applicable to Houellebecq’s humor.

Within these works there is a little something to offend nearly everyone. Critics have called Houellebecq’s novels racist, depressing, sexist, anti-progressive, Islamophobic, anti-modern, pornographic, and just plain vulgar. There is some basis of truth in all these criticisms, and yet something about Houellebecq’s novels rings hauntingly true to modern life. And so they are widely read and discussed, with Houellebecq recognized as both the most famous living French novelist and a master stylist who holds up a mirror to the soul-deadening underside of the progressive mindset that has animated western European (and much of North American) social, political, and religious thought since the end of World War II.

Lost Souls

His works affirm the perception of Russell Kirk, who in an essay titled “Civilization Without Religion?,” wrote, “What many people mistake for the triumph of our culture actually consists of powers that are disintegrating our culture; that the vaunted ‘democratic freedom’ of liberal society in reality is servitude to appetites and illusions which attack religious belief, which destroy community through excessive centralization and urbanization; which efface life-giving tradition.”

Conservative commentator Rod Dreher has gone so far as to call Houellebecq a prophet, writing, “You can’t read the man’s disturbing novels without concluding that he understands something critically important about what it means to live today.”

There is about Houellebecq’s world a sense of lostness, a vision of men and women “whose souls, albeit in a cloudy memory, yet seek back their good, but, like drunk men, know not the road home,” as Boethius described humanity’s state many centuries ago. In the aptly titled Whatever, Houellebecq’s protagonist silently rages: “I don’t like this world. I definitely do not like it. The society in which I live disgusts me; advertising sickens me; computers make me puke.” The ideologues who promise the perfection of man and society have converted a great part of the twentieth-century world into a terrestrial hell, averred Kirk, as if anticipating Houellebecq.

Not surprisingly, there are few children depicted in this author’s novels, as the heirs of the sexual revolution tend to consider children superfluous and a burden. Likewise, relations between Houellebecq’s characters and their elderly parents tend to be cold and distant. These people live in a world in which the teachings of a living faith and knowledge of the permanent things have not been transmitted across generational lines, leaving them spiritually adrift and thus subject to immersion in a world of liquid modernity, where all givens, all the traditional institutions that make for rootedness, community, and stability, are steadily washed away. Therein, the skein of continuity across generations, the contract of eternal society, has been broken. People respond not to the witness of experience, history, church, tradition, or common sense, but to televised images and the disembodied voices on their devices. Without a firm ground of orientation, the modern can only “wander bewildered in new ways,” as Kirk once wrote.

These ways open into vistas of emptiness where even high achievement in one’s own vocation is met with a sense of indifference, in which boredom and a vague restlessness contend. In Platform, the main character muses: “What had I produced in the forty years of my existence? To tell the truth, not very much. I had managed information, facilitated access to it, and disseminated it. Sometimes, too, I had carried out bank transfers (on a modest scale; I was generally happy to pay the smaller invoices). In a word, I had worked in the service sector. It would be easy to get by without people like me.”

And why not? Immersed in the acid bath of modernity, many people today have come to view themselves as cogs and ciphers operating in a whirl of wet and dry machinery. Not surprisingly, their art reflects this truth; in The Map and the Territory, for example, Houellebecq sure-handedly depicts the modern art world, with its sanctimonious emphasis on here-today-gone-tomorrow styles of work that are as pretentious as they are irredeemably trivial. On this matter, Houellebecq’s credentials as a real-world prophet are affirmed by the earnest suggestion put forward by certain esteemed authorities that the roof of Notre Dame Cathedral, badly damaged by a fire in early 2019, be restored not with a steeple but with a swimming pool. In life as in fiction, the line between parody and prophecy has never been fuzzier.

Decadence and Decline

At least as early as 1954, Russell Kirk had detected the approaching twilight of the Western world. “A vague conviction that something is very wrong with modern life now seems to be general among men of a reflective turn,” he wrote in an essay titled “The Unbought Grace of Life.” “Vitality seems to have trickled away from our society; and the prospect before us is sufficient to affright even a political liberal or radical. The idea of progress is shattered. The men of the future, we are coming to fear, will be something less than men.” Amid the world of liquid modernity, the addictive tool of twenty-four-hour access to omnipresent electronic media has brought about what philosopher Marshall McLuhan termed the “obliteration of the person.” McLuhan once wrote that “man has become essentially discarnate in the electric age. Much of his own sense of unreality may stem from this. Certainly it robs people of any sense of goals or direction” (as quoted in W. Terrence Gordon’s McLuhan: A Guide for the Perplexed). Discarnate man has come into being.

McLuhan and Kirk, themselves devout Roman Catholics, might well agree that the modern age is caught in a death spiral of decadence, a phenomenon that predates the advent of electronic media. On this topic, Kirk frequently quoted the English philosopher C. E. M. Joad, whose book Decadence: A Philosophical Inquiry (1948) “sets down certain characteristics of a decadent society: luxury; skepticism; weariness; superstition; preoccupation with the self and its experiences; a society ‘promoted by and promoting the subjectivist analysis of moral, aesthetic, metaphysical and theological judgments.’ ” Kirk, in his essay “Permanence and Change,” adds wryly, “Anyone who does not recognize the acuteness of Joad’s analysis here—why, he must lead a life singularly sequestered.” Elsewhere, in The American Cause, Kirk explains: “A man is decadent who has ceased to have any aim in life; a society is decadent that no longer perceives goals and standards. . . . A decadent man and a decadent people ordinarily confess to no faults, because they have lost sight of the standards by which virtue and vice are determined.” Although discarnate man is not compatible with an incarnate Church and but marginally compatible with his traditionalist neighbors, he is thoroughly compatible with society’s would-be conditioners, controllers, and opinion makers.

In his novels, Houellebecq also remarks upon the depressing ugliness of modern architecture, which is boxy, utilitarian, and seems designed to have all the charm of a warehouse—not surprisingly since human beings are basically accounted as having no more intrinsic value than vermin. These brutalist structures are designed to affirm the status of human beings as mere democratic beings, ciphers, as free and equal as pigs in a sty. Kirk referred to this utilitarian development, in a column titled “Ugly Architecture Breeds Ugly Minds,” as “the architecture of servitude and boredom,” and remarked: “No previous civilization has been so dreadfully afflicted by ugly and shoddy building as is our present culture. We boast of our riches—and yet build as if we suffered from material poverty as well as poverty of imagination. . . . Ugliness in architecture is a breeder of ugliness in minds.”

Decadence—“ugliness in minds”—and its fruit are thus, as Kirk wrote in Enemies of the Permanent Things, “the consequences of defying normative truth: a failure of right reason, if you will, resulting in abnormality.” The West seems well along that road and its terminus in dissolution in the form of “suicide, violence, unnatural vices, drunkenness, addiction to narcotics, and even revolution.” “The malady of normative decay gnaws at order in the person and at order in the republic,” wrote Kirk, adding that if ethical understanding is ignored in modern letters and politics, “we are left at the mercy of consuming private appetite and oppressive political power. We end in Darkness.” Kirk’s dire warning is neither overly dramatic nor empty, for history has borne out the results of life in what might be called the Weimar West. The successful incubation of real-life acts of horror requires only time and pressure. As social commentator and novelist James Howard Kunstler has noted, “Extract all the meaning and purpose from being here on earth, and erase as many boundaries as you can from custom and behavior, and watch what happens, especially among young men trained on video slaughter games.”

Houellebecq recognizes this, and though he has no words of hope, he is unsparing in his exposure of Western purposelessness. He is like a man living in a society in which nobody ever learned how to swim, now standing on the bank of a deep pool watching someone drown: He has forsworn a crucial piece of life-saving knowledge and now can only watch helplessly as the natural consequences unfold. He knows something is wrong and he knows the reason why, but he cannot act: he can only describe the passing scene.

Twilight of the Gods

“What ails modern civilization?” wrote Kirk in “Civilization Without Religion?”—answering his own question as follows: “Fundamentally, our society’s affliction is the decay of religious belief. If a culture is to survive and flourish, it must not be severed from the religious vision out of which it arose.” Here, Kirk echoes Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s famous recollection of a remark spoken by the older generation of Russians during his youth, men and women who remembered their nation before it fell victim to Stalin’s murderous policies: “Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.”

That may well be true, but a momentous question overshadows it: If a person has already slammed shut and locked the final escape hatch, if he has said no to the possibility of the existence of the Divine and instead embraces nothing of value higher than the cash nexus or the opinions of the latest voice on the telescreen, how can he find joy and a reason to live? How do we find our way to God or a sense of hope (however glimmering) now that hopefulness and religious belief have become out of reach for modern, educated people? And what of those men and women, heirs of a rich cultural tradition, who have never believed in God in the first place? (“I had not only never held any religious belief, but I hadn’t even envisaged the possibility of doing so,” admits one of Houellebecq’s characters in The Possibility of an Island. “For me, things were exactly as they appeared to be: man was a species of animal, descended from other animal species through a tortuous and difficult process of evolution; he was made up of matter configured in organs, and after his death these organs would decompose and transform into simpler molecules; no trace of brain activity would remain, nor of thought, nor, evidently, of anything that might be described as a spirit or a soul.”)

Like Henry Adams, Houellebecq recognizes the truth, beauty, wisdom, and power of Europe’s Christian past—achieved when the continent was known as Christendom—though he cannot come to faith. He has written of his astonishment at the rapidity with which the Christian faith has collapsed in Europe since the end of World War II. As he says in The Possibility of an Island:

In countries like Spain, Poland, and Ireland, social life and all behavior had been structured by a deeply rooted, unanimous, and immense Catholic faith for centuries. It determined morality as well as familial relations, conditioned all cultural and artistic productions, social hierarchies, conventions, and rules for living. In the space of a few years, in less than a generation, in an incredibly brief period of time, all this had disappeared, had evaporated into thin air. In these countries today no one believed in God anymore, or took account of him, or even remembered that they had once believed; and this had been achieved without difficulty, without conflict, without any kind of violence or protest, without even a real discussion, as easily as a heavy object, held back for some time by an external obstacle, returns as soon as you release it, to its position of equilibrium. Human spiritual beliefs were perhaps far from being the massive, solid irrefutable block we usually imagined; on the contrary, perhaps they were what was most fleeting and fragile in man, the thing most ready to be born and to die.

Without the bedrock of a living religious faith, dignity and purpose are mere constructs of the mind, subject to age and circumstance, a fact Houellebecq knows. He has intuited the truth expressed by George Orwell, that wisest of leftists, in his novel The Clergyman’s Daughter: “Faith vanishes, but the need for faith remains the same as before.” Grounded in Classical and Christian knowledge, Houellebecq’s scholarly character Djerzinski proclaims, in The Elementary Particles: “Love binds, and it binds forever. Good binds while evil unravels. Separation is another word for evil; it is also another word for deceit. All that exists is a magnificent interweaving, vast and reciprocal.” Djerzinski is on to something essential, but he can get no further than this assertion.

Intriguingly, in his study Without God: Michel Houellebecq and Materialist Horror (2016), Louis Betty demonstrates that despite initial perceptions, Houellebecq “is a deeply and unavoidably religious writer” who lays much of the blame for modern malaise at the foot of humankind’s oldest enemy: idolatry in the form of materialism and its discontents. The novelist perceives the unfettered free market as a forum that provides much good, much comfort, and much luxury at a cost: a devil’s bargain that produces a desire to acquire ever more of the same, which diminishes man’s capacity for fellowship and community while destroying his sense of the sacred. It’s as J. R. R. Tolkien once wrote to his eldest son: “Commercialism is a swine at heart.” The preoccupation with mere getting and spending is both a symptom of cultural decay and a destroyer of imagination. Tolkien foresaw what Houellebecq depicts: the end of Christendom—Christian Europe—amid a self-induced postwar fever of hedonism, aimlessness, and nihilism. “More and more now, I have doubts about the sort of world we’re creating,” confides one of Houellebecq’s characters, in Platform.

Those doubts are well founded. But materialism alone is not at fault. “Material forces have had a large part in this transformation of life,” wrote Kirk, “but more and more, I say, we are coming to understand that certain powerful tendencies of the intellect have been quite as active in the destruction of the unbought grace of life.” That phrase “the unbought grace of life,” which Kirk used as the title of his essay, was an expression coined by Edmund Burke denoting honor (with all that word implies regarding matters of character, integrity, and the human spirit) as one of the cultural elements that make for a good and fulfilling life. Kirk has noted that culture is not simply a matter of matronly snobs wielding lorgnettes as they stroll through museums while declaiming loftily of “artistic values,” but rather, as he wrote in the introduction to his essay collection The Intemperate Professor and Other Cultural Splenetics, “the whole complex of imagination, sentiment, artistic achievement, and elevation of character which distinguishes the civilized man from the brute. Virility and culture are intertwined and complementary, not opposed. As modern culture decays, so modern manliness sinks, for both arise from life and dignity and purpose.”

Kirk declared in Eliot and His Age:

Culture is that which makes life worth living. All culture arises out of religion. When religious faith decays, culture must decline, though often seeming to flourish for a space after the religion which nurtured it has sunk into unbelief. But neither can religion subsist if severed from a healthy culture; no cultured person should remain indifferent to erosion of apprehension of the transcendent.

A jeering contempt for one’s own formative heritage is no sign of maturity but instead may be a thoughtless step toward a larger and more profound dissolution. The high necessity of reflective men and women, Kirk wrote in “Civilization Without Religion?,” is to shore up that which remains and “to labor for the restoration of religious teachings as a credible body of doctrine.”

Thinking Hope

“Human nature suffers irremediably from certain grave faults,” wrote Kirk in his essay “Ten Conservative Principles.” “Man being imperfect, no perfect social order ever can be created. . . . All that we can reasonably expect is a tolerably ordered, just, and free society, in which some evils, maladjustments, and suffering will continue to lurk.” This proposed tolerance for imperfection runs entirely against the conscience of the West’s thought leaders, who believe that every injustice must be vindicated, every monster destroyed, and every wrong righted in the cause of the greater good. But with human nature being what it is, a maddening, remarkable mixture of meanness and greatness, heaven on earth can never be achieved. Wisdom recognizes this fact and seeks to accommodate human imperfectability in a delicate balancing act of tolerance, enforcement, and benign neglect. “By proper attention to prudent reform,” wrote Kirk, “we may preserve and improve this tolerable order. But if the old institutional and moral safeguards of a nation are neglected, then the anarchic impulse in humankind breaks loose: ‘the ceremony of innocence is drowned.’ ” In his novels, Houellebecq faithfully records the drowning ceremony; he is a witness to it, not a contributing cause of it. His novels depict a Western people of worry and of shame, with no message of hope to deliver.

Outside the world of literature, what might be done to stem the spread of the mindset of decadence and despair? As he recounts in his memoir The Sword of Imagination, during a period of cultural upheaval in the United States, Kirk once advised an American president:

Despair feeds upon despair, hope upon hope. If most people believe the prophets of despair, they will . . . cease to cooperate for the common good. But if most people say, “We are in a bad way, but we have the resources and the intelligence and the will to work a renewal”—why, they will be roused by the exigency to common action and reform. It is all a matter of belief.

To turn back encroaching despair by showing people a hopeful alternative way would seem to be the great endeavor, a Herculean task. But as the old adage runs, “Nothing is, but thinking makes it so.” That goes along with the courage to begin what Kirk might counsel: the difficult and seemingly unrewarding task of cultural renewal, a lifelong task for which there is no pat, detailed instruction guide.

The preliminary spadework for this endeavor begins with seeing clearly the actual nature of today’s culture and cutting through the glib verbiage by which decadent beliefs and practices are upheld. Those who would renew the West must clearly and effectively articulate the standards by which to identify decadence in belief and practice, providing examples of how the West has declined and what that portends. “A recovery of norms can be commenced only when we moderns come to understand in what manner we have fallen away from old truths,” as Kirk wrote in Enemies of the Permanent Things.

This will involve laboring to recover the lost object, to discover the reason for living. As Houellebecq has noted throughout his works, that reason for living does not lie in acquiring wealth and possessions. Early in his career, in a 1954 speech later incorporated into Prospects for Conservatives, Kirk discoursed eloquently on this matter, noting that the enlightened conservator

does not believe that the end or aim of life is competition; or success; or enjoyment; or longevity; or power; or possessions. He believes, instead, that the object of life is Love. He knows that the just and ordered society is that in which Love governs us, so far as Love ever can reign in this world of sorrows; and he knows that the anarchical or the tyrannical society is that in which Love lies corrupt. He has learnt that Love is the source of all being, and that Hell itself is ordained by Love. He understands that Death, when we have finished the part that was assigned to us, is the reward of Love. And he apprehends the truth that the greatest happiness ever granted to a man is the privilege of being happy in the hour of his death.

He has no intention of converting this human society of ours into an efficient machine for efficient machine-operators, dominated by master mechanics. Men are put into this world, he realizes, to struggle, to suffer, to contend against the evil that is in their neighbors and in themselves, and to aspire toward the triumph of Love. They are put into this world to live like men, and to die like men. He seeks to preserve a society which allows men to attain manhood, rather than keeping them within bonds of perpetual childhood. With Dante, he looks upward from this place of slime, this world of gorgons and chimeras, toward the light which gives Love to this poor earth and all the stars.

The object of life is Love. Here Kirk articulates a truth that Houellebecq senses and struggles toward in his novels. It is not a Lennonesque imagine-there’s-no-heaven form of love—enervated, ethereal, and altogether nominal in the here and now. Rather, in all his works Kirk pointed toward the possibility of an island, seeking to direct his readers’ gaze upward toward the light of God, which gives Love to this poor earth. Emulating Kirk, cultural conservators must seek ways to recover a sense of the sacred and offer life-affirming alternatives to the decadent practices of the present day. To reorient the lonely individual and restore true community through the nurturing of spirit and character will require prudent wisdom, effort, and sacrifice, calling forth all the wisdom, boldness, and active imagination possessed by the rising generation.

These endeavors may be costly in terms of one’s reputation and livelihood. In this regard, the cultural conservator is no Pollyanna. As Tolkien wrote in one of his letters, he does not expect the progress of history “to be anything but a ‘long defeat’—though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.” Barring the collapse of civilization into anarchy, rebuilding and renewal will be the central challenge to men and women of goodwill during the next decades of this century.

A culture that is in decay may take many generations to reform, and the progress of reform is agonizingly slow, like the growth of an oak. But where a remnant of men and women of courage, character, and virtue remain, there is hope.

James E. Person Jr. is the author of Russell Kirk: A Critical Biography of a Conservative Mind and the editor of Imaginative Conservatism: The Letters of Russell Kirk.