The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple

By Jeff Guinn

(Simon & Schuster 2017)

Cult City: Jim Jones, Harvey Milk, and 10 Days That Shook San Francisco

By Daniel J. Flynn

(ISI Books 2018)

On November 18, 1978, more than nine hundred people—including many children—were poisoned or shot to death at a bizarre cult compound in a South American jungle. California congressman Leo Ryan, who was on a fact-finding mission, was among the victims, but they were overwhelmingly poor expatriates from California, many elderly pensioners. The horrific Jonestown massacre was the largest loss of civilian life in American history prior to 9/11 and remains the largest mass suicide in modern times. Yet the fortieth anniversary of the historic tragedy in Guyana went largely unnoticed. It is as if the maniacal cult leader, Jim Jones—founder of the so-called Peoples Temple—never existed and his grotesque handiwork never happened.

This is by design. Americans are still fascinated by Charles Manson’s murderous crime spree in the late 1960s, and popular culture dwells on other cult leaders, such as David Koresh, whose followers perished in a fiery shootout with federal officers in 1993. We remember the gun battle and conflagration that took the lives of seventy-six Branch Davidian cult members outside Waco, but the far greater carnage at Jonestown has largely faded, save for the popular expression, now sanitized from its ghastly origins, “drinking the Kool-Aid.” Even the expression—a common metaphor for groupthink—is imprecise. The deadly, cyanide-laced beverage imbibed to lethal effect in Jonestown was actually a cheap knockoff, Flavor Aid.

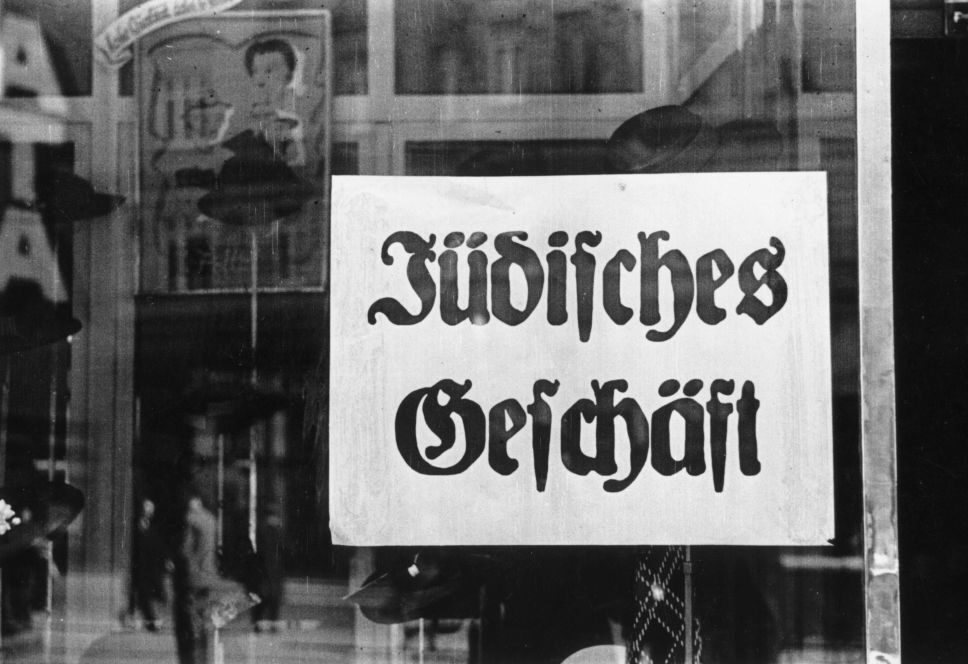

All violent crime is heinous, but why have the media tended to ignore the epic villainy of Jim Jones while endlessly harping on incidents such as the 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard and the 2015 church shooting by deranged loner Dylann Roof ? Why are largely defunct groups such as Aryan Nations and the KKK tirelessly publicized, while key details of the deadliest cult in American history are swept under the rug—conveniently ignored? The short answer is: ideology. Jones was a radical leftist, and when based in San Francisco he oversaw a formidable political organization that catered to numerous Democratic candidates and elected officials, who embraced him warmly. Jones was a darling of many prominent liberal politicians, up to the macabre end.

Then—poof!—Jones suddenly disappeared down the memory hole.

Santayana famously said that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” but even worse than forgetting the past is deliberately distorting it. Jones is forgotten, or the facts willfully misrepresented, because the truth is painful to the left. To the extent Jones is recalled at all, he is depicted as a well-meaning religious leader who succumbed to madness after moving his flock to a communal sanctuary in the rain forest. This account is a fabrication, providing cover for his countless enablers and defenders, who have largely avoided culpability for their ignominious role in the monstrous tragedy. Two recent books aim to set the record straight. The following summary is drawn from their meticulous narratives.

While Jones posed as a “Reverend,” and began his itinerant career in Indiana as a Bible-quoting hustler-cum-minister, he was always a committed Marxist, and his true gospel was socialism. Phony faith healings and sham mind readings were part of his hustle, and the ambitious Jones emulated the tactics of another charlatan, the Philadelphia-based Father Divine, a self-anointed messiah who lived lavishly and maintained a harem of supplicant female acolytes. Jones cultivated a mixed-race congregation in Indianapolis, which provoked controversy in the 1950s, but what prompted the increasingly erratic Jones to move his congregation—the Peoples Temple—to Northern California in 1965 was the irrational fear of nuclear annihilation. Thirteen years later, Jones’s growing paranoia would spiral out of control, with destructive consequences.

In the Bay Area, Jones found a receptive audience for his mixture of socialism and racial healing. Jones’s native cunning, personal charisma, and endless drive made him an effective leader, even as his behavior became addled by drug abuse, rampant bisexual promiscuity, and megalomania. Many lost souls were looking for answers in the tumultuous sixties, especially in California, and the ever-manipulative “Father” Jones preyed on their vulnerability and naivete, even as his message strayed from the pseudo-religious to the purely political. Eventually Jones spurned Christianity altogether, urging his followers to use the Bible as toilet paper and to regard him as god instead.

So far this may seem like a fairly conventional—albeit engrossing—tale of a crazed cult leader and his gullible, deluded flock. An unsteady con man, once arrested for soliciting homosexual sex in the bathroom of a Los Angeles movie theater, who went over the edge. And so it is—up to a point. The most fascinating aspect of the story, airbrushed out of most contemporary accounts, is the extent to which the fanatical Jones was embraced by prominent political leaders prior to the fateful (and gruesome) denouement at Jonestown. The complicity of these figures, especially San Francisco county supervisor Harvey Milk—who was assassinated shortly after the Jonestown massacre in an unrelated (but equally bizarre) incident—has gone unnoticed, or been conveniently forgotten.

Jeff Guinn, the bestselling author of a 2013 biography of Charles Manson (Manson), brought the “real” Jim Jones into focus in 2017 with a definitive biography, entitled The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple. Guinn portrays Jones as a misfit sociopath raised as an only child by a domineering, eccentric mother and an ineffectual, semi-invalid father. Jones’s austere upbringing left him with a lifelong chip on his shoulder against society’s haves, and an abiding identification with the have- nots. This may explain Jones’s early and aggressive embrace of socialism, and his eventual infatuation with communism. (Jones made a pilgrimage to Cuba in 1960 following the revolution led by Fidel Castro, and returned in 1977. He chose Guyana in part because it was a socialist country and hoped to relocate his commune to the Soviet Union.) Guinn’s account is thorough and compelling, with abundant notes and a detailed index.

Daniel Flynn’s 2018 book, Cult City, is shorter than The Road to Jonestown (222 pages of text, compared to Guinn’s 468), but just as painstaking and well-researched. In contrast to Guinn, Flynn follows Jones’s trajectory after his arrival in California and concentrates on the parallel paths of Jones and Harvey Milk, the openly gay Navy veteran who was elected to the San Francisco County Board of Supervisors in 1977 and murdered, along with Mayor George Moscone, a year later, on November 27, 1978. Overlapping slightly with Guinn, Flynn unravels the “real” story of Jonestown but places equal importance on debunking the mythology that has enshrouded Milk following his death. Ironically, the fortieth anniversary of Milk’s assassination received more media attention than the Jonestown massacre.

Milk has been canonized as a martyr for the LGBT cause, although—contrary to the popular narrative—the motivation of the killer, Dan White, had nothing to do with anti-gay animus. The prideful and unstable White (who eventually committed suicide), once a colleague and occasional ally of Milk on the Board of Supervisors, was distraught over the mayor’s refusal to reinstate White after he improvidently resigned from the board. The widely held belief that White was a bigot who killed Milk because he was gay is totally unfounded, Flynn convincingly demonstrates. Contrary to hagiographic biographies and the 2008 movie, Milk, starring Sean Penn, Milk was a smarmy hustler killed senselessly by an erratic acquaintance.

Following his death, San Francisco’s emerging identity as an LGBT mecca, and Milk’s status as the state’s first openly gay elected official, molded Milk into a cultural icon. President Obama posthumously awarded Milk the Presidential Medal of Freedom. A postage stamp bore his image. A Navy ship bears his name. California created a state holiday in his honor. The San Francisco airport terminal was renamed in tribute to him. As Flynn points out, the most striking aspect of the deification of Milk is the omission of any reference to Jim Jones. Yet Milk was an enthusiastic booster of Jones and relied on the grassroots support of the Peoples Temple to win his seat on the Board of Supervisors.

Milk was not the only politico to cozy up to Jones. George Moscone, nicknamed “the people’s mayor,” owed his narrow victory in the 1975 mayoral runoff to the volunteer army (and perhaps ballot box stuffing) of Jones’s loyal disciples. Many observers felt that Jones helped Moscone steal the election. After taking office as mayor of San Francisco, Moscone rewarded Jones with a patronage appointment to the city’s Housing Authority Commission. Because of the size of Jones’s primarily African American congregation, and Moscone’s success in the 1975 runoff, Jones became a sought-after resource to other pols. As Flynn reports,

Given the Temple’s power in numbers, politicians rushed to befriend Jones. Much of California’s Democratic establishment visited the Peoples Temple, including Governor Jerry Brown, Lieutenant Governor Mervyn Dymally, Congressman Phil Burton, Assemblyman Willie Brown [who later became speaker and then S.F. mayor], and Mayor Moscone.

Jones shared the podium with Rosalynn Carter at a 1976 campaign event for her husband, Jimmy. Jones was invited aboard Walter Mondale’s chartered jet when the vice-presidential candidate made an appearance in San Francisco. Serial candidate Milk also became a patron of the Peoples Temple, occasionally attending services there and writing fawning letters of praise to and on behalf of Jones. Jones reciprocated by helping Milk’s various campaigns with publicity, volunteer support, and an invitation to speak at the Peoples Temple. Milk’s previous defeats paved the way to a successful 1977 campaign for a seat on the Board of Supervisors.

When Jones was criticized in the media for his questionable conduct, Moscone, Brown, Dymally, Milk, and others leapt to his defense. Even after Jones moved his followers to the untamed jungle in Guyana, his political allies continued to intercede on his behalf. In 1978, mere months before the Jonestown massacre, Supervisor Milk wrote a long letter to President Jimmy Carter in support of Jones, who was facing legal problems involving federal authorities. In the letter, Milk described Jones as “a man of the highest character” and vouched for his reputation in the community. Milk wrote similar letters to the Guyanese prime minister and Carter’s HEW secretary, Joseph Califano.

Even as the conditions in Jonestown deteriorated into physical abuse and intimidation resembling a concentration camp, Jones’s sycophantic allies in the U.S., including Huey Newton and Angela Davis, called on the phone to give speeches broadcast to Jones’s beleaguered followers via a public address system. Flynn recites the grim litany chapter and verse, naming all the enablers and quoting damningly from their craven defense of one of America’s worst monsters. His gripping account is both mind blowing and stomach turning.

How can a dishonest biopic glorifying Milk—without even a mention of Jones—win two Academy Awards? How can any of the politicians who defended and advocated on behalf of Jones escape the contempt of history? How can Carlton B. Goodlett, a far-left political activist and civil rights advocate who was one of Jones’s fiercest defenders, both before and after the horror of Jonestown, be the namesake for the street in San Francisco in front of city hall?

Only by a willful blindness to the grim history of a psychopathic Marxist cult leader who forced his deluded followers to drink poison in an act of “revolutionary suicide.”

The story told by Jeff Guinn and Daniel Flynn in their riveting books would be deemed too far-fetched to believe, except that it actually happened. We ignore it or forget it at our peril. Some of the same people who praised and supported Jones are hell-bent on removing historic statuary all across America, renaming schools, streets, and parks, and rewriting the history taught to our children. The Road to Jonestown and Cult City are indispensable reminders of the truth, a chronicle of a remarkable era in our history, and a sobering parable of utopian thinking run amok. ♦

Mark Pulliam, who blogs at Misrule of Law, is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in City Journal, the Wall Street Journal, National Review, and many other publications.

Founded in 1957 by the great Russell Kirk, Modern Age is the forum for stimulating debate and discussion of the most important ideas of concern to conservatives of all stripes. It plays a vital role in these contentious, confusing times by applying timeless principles to the specific conditions and crises of our age—to what Kirk, in the inaugural issue, called “the great moral and social and political and economic and literary questions of the hour.”